- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

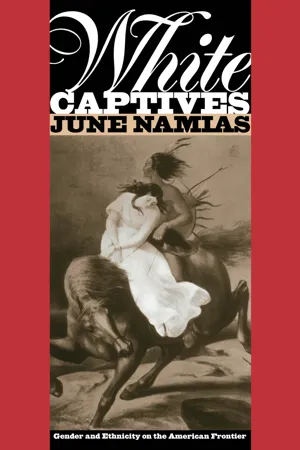

Yes, you can access White Captives by June Namias in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

White Actors on a Field of Red

1. White Women Held Captive

O, the wonderful power of God that I have seen, and the experiences that I have had! I have been in the midst of roaring Lions, and Salvage Bears, that feared neither God nor Man, nor the Devil, by night and by day, alone and in company, sleeping all sorts together, and yet not one of them ever offered the least abuse of unchastity to me in word or action.

—Mary Rowlandson

—Mary Rowlandson

They drank freely, and soon became stupid and senseless. With one of their tomahawks I might with ease have dispatched them all, but my only desire was to flee from them as quick as possible. I succeeded with difficulty in liberating myself by cutting the cord with which I was bound.

—Mrs. Jordan

—Mrs. Jordan

I was stripped of my gown, shawl, stockings and shoes; loaded with as many of the packs which the boat contained as could be piled upon me, and compelled in this manner to accompany the Indians through a pathless wilderness, for many a tedious mile—not privileged to embrace or nurse my infant babe, which was but eleven months old, and which was carried in a fur sack, by one of their young squaws.

—Eliza Swan

—Eliza Swan

To undertake to narrate their barbarous treatment would only White add to my present distress, for it is with feelings of the deepest mortification that I think of it, much less to speak or write of it.

—Rachel Plummer

—Rachel Plummer

“On the tenth of February, 1675 came the Indians with great numbers upon Lancaster.” So begins the first narrative of North American captivity in the English language. In a single paragraph its writer, Mary Rowlandson, rivets her reader’s attention on a catastrophic scene of a small community in mayhem—men’s bodies split open, houses and barns in flames, members of her household “fighting for their Lives, others wallowing in their Blood! . . . Mothers and Children crying out for themselves, and one another, Lord, what shall we do!”1

Years after Mary Rowlandson wrote these lines, hundreds of captivity stories followed her lead. Men’s and women’s narratives almost always began with a frightful scene of capture, often accompanied by murder, dismemberment, or maiming of some family member, and perhaps fire to one’s home or the violent interruption of migration. Progressing from a confrontation between whites and Indians, narratives continued en route with the Indians to the Indian camp, then followed, like Rowlandson’s, with a discussion of life there and concluded with an escape, a rescue, or some other means of return (with the few exceptions of narratives of those who never returned).

For each sex and in different periods, there are many accounts of white captivity and many responses to it. For men and women, the once clear and penitent Puritan narrative later became more formulaic. The captivity stories of white men and women have many other similarities as well. But the details of the experience and the way the accounts—real and imagined—were described differ according to gender. By comparing accounts and representations by and about men with those about women but by both men and women, we notice some major differences not only in tone and style but in experience and response. We can also speculate on why such stories held an American readership for so long.

Joan Scott defines gender as “knowledge about sexual difference” and “the understanding produced by cultures and societies of human relationships, in this case of those between men and women.” She finds that in historical presentation there has Held been a “remarkable absence or subordination of women,” confining them to “the domestic and private” spheres, thus enforcing a set of “priorities” and “categories” which diminishes their importance.2 But rather than being marginalized, subordinated, or totally missing, white women captives are the subject of a vast array of materials. In this literature white women participate fully in the so-called rise of civilization. In fact, what is significant about seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century representations of this material is that women are not only there, but they are frequently at the center of stories, histories, and illustrations.

Looking at captivity materials from 1607 through the nineteenth century one cannot miss the gendered nature of the depictions. Often European or American men and women were undergoing similar if not identical experiences, but these were represented in startlingly different ways. They also allegedly reacted to Indian attack and captivity or potential captivity differently and in very gendered ways. Here again, Scott is useful: “The story is no longer about the things that have happened to women and men and how they have reacted to them; instead it is about the subjective and collective meanings of women and men as categories of identity have been constructed.” The use of gender as a lens is helpful here because women are so prominent. We need to ask how they are represented and why.3

Captivity materials, especially those from the late eighteenth century, are notorious for blending the real and the highly Active. In this book, works about historical figures are examined, but it is the production, reproduction, and use to which these stories have been put rather than the veracity or lack of it in the accounts with which I am concerned. Besides folk heroes, folk heroines, and folk victims shaped to justify the ruling national political purpose, as Richard Slotkin and Roy Harvey Pearce have told us, there are gendered archetypes asserting a gender ideology as a piece of the national and domestic mission and, perhaps, as normative behavior.4

What constructions of gender do these materials show us? Despite the perils of overgeneralizing an enormous literature in surveying hundreds of captivity narratives, western history books, schoolbooks, newspaper accounts of capture, and the like, particular archetypes appear again and again. In the period between 1675 and 1870 these female types can be called the Survivor, the Amazon, and the Frail Flower.

This typology best describes female captives who appear in an analysis of over fifty North American captivity narratives.5 All three types originate in the colonial era, but the preponderance of each varies over time and place. Survivors predominate in the colonial era, Amazons flourish in the period of the Revolution and the Early Republican era, and Frail Flowers are most evident in the period 1820–70. The archetypes themselves, although exhibiting continuities, change over time, territory, and with different Indian groups. Indian groups and practices change with the move west. After the Revolution the new republic pushed many native groups west, and nineteenth-century plains warfare grew increasingly ferocious. These political and ethnic dimensions had important implications for Anglo-American women.

But first, who were the white women captives? Except for young children, married women between the ages of twenty and forty-five predominated. Most were English or Anglo-American Protestants, usually from frontier regions. On the Pennsylvania frontier there were also German captives; on the Minnesota frontier, Germans and Scandinavians were among the white captives. Most were mothers of young children and. in the cases of the older women, were parents to both young and adolescent children. With the exception of ministers’ wives and daughters, these women were usually homesteaders of yeoman, artisan, or middle-class backgrounds. Those who wrote their own narratives were better educated. What does the typology tell us about the way white women’s captivity was written about and otherwise portrayed?

Survivors

Rowlandson most typifies the Survivor, She is not a 25 passive victim, a racist, or a Puritan pawn. She is a woman supremely tried. She watches as her frontier Massachusetts fortress goes up in flames, her relatives and neighbors are murdered, her baby dies of exposure, and her other children disappear. Separated from her husband and children for thirteen weeks, not knowing, except for a brief meeting with her daughter, whether they are dead or alive, she renews and reconceives her faith in God. She also becomes a supreme negotiator with the Narragansetts and Wampanoags among whom she finds herself. She uses her considerable strength to learn to live among these Algonquians.6 She sews and exchanges goods with them. After several weeks, she moves from disgust with native fare to relishing bear’s foot. She makes fast friends with Metacomet (King Philip). Like Rowlandson, Survivors show a range of feelings from extreme powerlessness to aggressive hostility. Yet they all adapt, survive, and make sense of and, in a sense, bear witness without undue victimization, personal aggrandizement, or genocidal aggression.

Ten of the eleven Survivors were captured within the period 1675–1763; eight were New Englanders. The preponderance of the Survivor type in the early period neatly fits the quantitative findings of Alden Vaughan and Daniel K. Richter, which confirm the high survival rate of female captives. Of 592 known female captives of all ages they found that fewer than 10 percent died of various causes in captivity or were killed. Between 30 and 37 percent remained with French or Indians, and 44 percent returned to New England. The quantitative data fit the image portrayed in the Puritan narratives. But though the stories highlight inner fortitude, these women and girls survived forced winter marches like the Deerfield exodus through the New England wilderness into Canada often with the close cooperation of New England or Canadian Indians or the French. These early Anglo-American women and children were tough. both physically and emotionally. Over 20 percent (22.5) of their sex who were taken captive were prisoners for one or more years.7 How did they manage?

First, their captors should be credited. Although many of the Survivors chose not to remain with Indians, and any number can be cited for venomous remarks about Indians, these women were willing to give credit when it was due. Others, as James Axtell has told us, did stay, were adopted by their captors, and refused several attempts to be “redeemed” or repatriated into white society.8

But for their own part, many English and Anglo-American women did well in marches through Indian country. Mary Rowlandson and Elizabeth Hanson expressed fear and depression. Rowlandson became despondent after losing her baby and being separated from her husband and children. At the site of their first encampment she was thrown into despair. “All was gone, my Husband gone (at least separated from me, he being in the Bay; and to add to my grief, the Indians told me they would kill him as he came homeward) my Children gone . . . all gone (except my life) and I knew not but the next moment that might be too.” But almost immediately she assessed her choices: she remembered her earlier thoughts: “If the Indians should come, I should chuse rather to be killed by them, than taken alive. but when it came to the trial my mind changed: their glittering Weapons so daunted my Spirit, that I chose rather to go along with those (as I may say) ravenous Bears, than that moment to end my daies.”9

Those days passed, and she felt lost in a “vast and desolate Wilderness, I know not whither.” She lamented leaving behind “my own country, and traveling to the vast and howling Wilderness; and I understood something of Lot’s Wife’s Temptation, when she looked back.” By their eighth site she was overwhelmed.

When I was in the Cannoo, I could not but be amazed at the numerous Crew of Pagans, that were on the Banks of the other side. When I came ashore, they gathered all about me, I sitting alone in their midst. . . . Then my heart was began to faile: and I fell a weeping; which was the first time to my remembrance, that I wept before them. Although I had met with so much Affliction, and my heart was many times ready to break, yet I could not shed one tear in their sight; but rather had been all this time in a maze, and like one astonished; but now I may say, as Psal.137.1 By the Rivers of Babylon, there we sate down and, yea, we wept when we remembered Zion.

One Indian asked her why she was crying, and she said she was afraid they would kill her. “No, said he, none will hurt you.” And one of the Indians came forward with “two spoonfuls of Held Meal (to comfort me).”10 She went on to make the most of her Captive stay and to befriend some of her captors.

Mary Rowlandson was clearly a remarkable woman. As a minister’s wife she was not typical of New England women of her time. She was a member of the elite and a highly literate and powerful writer.11 Her account shows a strength and self-awareness unusual in any period. But several accounts show that other daughters of New England employed accommodation and ingenuity for their own benefit. Elizabeth Hull Heard was the daughter of a minister, mother of five sons and five daughters, and a “widow of good estates.” When Dover, New Hampshire, was attacked in 1689, the widow told her children to abandon her and “shift for themselves” because “through her despair and faintness”—according to Cotton Mather—she was “unable to stur any further.” When they left she tried to move downriver surrounded by “blood and fire, and hideous outcries.” She finally sat down by a bush and “poured out her ardent prayers to God for help in distress.” Soon “an Indian came toward her, with a pistol in his hand.” He came back twice but let her go.12

Cotton Mather presents this as a “Remarkable Escape,” but Samuel G. Drake gives additional information. During an earlier attack on Dover in 1676, “this same Mrs. Heard secreted a young Indian in her house, by which means ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- White Captives

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations and Maps

- Preface

- White Captives: An Introduction

- Part One White Actors on a Field of Red

- Part Two Women in Times of Change

- Conclusion Women and Children First

- Appendix Guide to Captives

- Notes

- Index