- 398 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Dispelling much of what he terms the 'mythology' of the Scotch-Irish, James Leyburn provides an absorbing account of their heritage. He discusses their life in Scotland, when the essentials of their character and culture were shaped; their removal to Northern Ireland and the action of their residence in that region upon their outlook on life; and their successive migrations to America, where they settled especially in the back-country of Pennsylvania, Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia, and then after the Revolutionary War were in the van of pioneers to the west.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Scotch-Irish by James G. Leyburn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Poverty and Insecurity

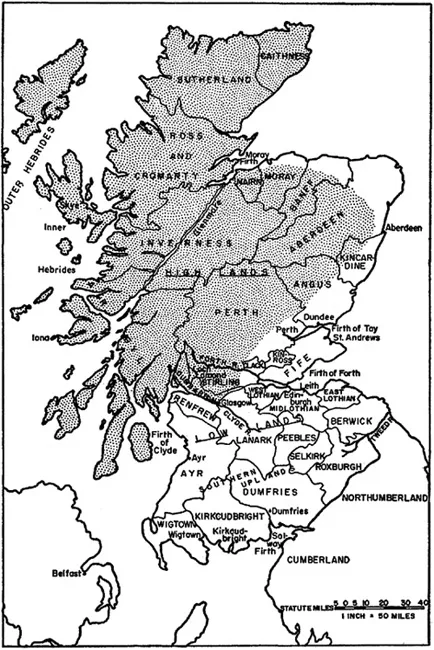

SCOTLAND IS, BY AMERICAN STANDARDS, a small country. With its 30,405 square miles, it is approximately the size of Maine or of South Carolina. At least three-fifths of its territory comprises the Highlands of the north and west and the islands off the west coast; in these regions the soil is so scanty and the climate so difficult that farming is often impossible. In 1600 only about half a million people lived in the whole country, and only the capital, Edinburgh, had as many as ten thousand. All towns, and a majority of the population, were in the Lowlands, the territory south of the narrow waist of Scotland between Glasgow and Edinburgh, and the coastal strip north of Edinburgh. In the interior parts of the Lowlands are high hills and moors known as the Southern Uplands; but although some of its prominences rise more than twenty-five hundred feet, the south has no such proliferation of isolated valleys and inaccessible places as abound in the Highlands. Every royal burgh in old Scotland, like practically every modern city, was within ten miles of the sea.

In 1600 Scotland had never known orderly government or a rule by law instead of by men, nor had the country ever, for many years at a time, known peace. Life everywhere was insecure, not only because of recurrent wars with the English, but even more because of abominable economic methods, a niggardly soil, and constant cattle raiding and feuds.* No policemen kept order. Although there was a large measure of local justice, Scots had not yet learned general respect for property rights, nor had they been converted to admiration for principles of law and impersonal justice. Royal burghs and farm “touns” were mere villages with filthy mudholes for streets and foul shanties for the average inhabitant to live in.

* Scotland had its Wild West much earlier and much longer than did the United States. It is not much of an exaggeration to say that, if in America there was no law west of the Missouri, similarly in Britain there was no law north of the Tweed, except as one lord was powerful enough to keep peace on his own lands.

Scotland was a poor country. Scots themselves had a wry saying that when the Devil showed all the countries of the world to our Lord, he kept his “mickle thoomb” upon Scotland.*1 A later poet concluded that

Had Cain been Scot, God had ne’er changed his doom,

Not made him wander, but confined him home.2

Not made him wander, but confined him home.2

The best of its farming land was in the eastern Lowlands, between the English border and Edinburgh; but this was the very region most open to constant English invasion and depredation. The southwestern Lowlands had a thin soil. Stony moors covered with heath and whin, long stretches of bog and moss in the lower districts, gravelly soil along the coast, and numerous burns and lochs, more plentiful then than now, made farming difficult under any circumstances, and especially for a people who had no knowledge of drainage and who used only the most primitive methods and implements.

The Lowland countryside in 1600 hardly resembled what it is now, for it was practically treeless. The region had once been covered with woods, but the continued waste of timber had made trees almost disappear everywhere except around the houses of a few lairds. A traveler might walk many miles (and he must either walk or pick his way on horseback over unkempt paths, since there were no roads nor any public conveyances) without even seeing a bush. To such an extent had the land been denuded in the south that Parliament passed several laws to encourage the planting of trees and to prevent mischievous persons from injuring young trees,† Despite such laws, little timber was grown, and consequently there was no wood for building and little for furniture; certainly there was none for shipbuilding, an enterprise Parliament would have liked to encourage.

* In the pages that follow, references to and citations from authorities, with no information of general interest to the reader, will be numbered and relegated to a special section, NOTES, at the end of the book.

† For example, if anyone did damage to a young tree, he was to be fined £.10 for the first offense and £20 for the second; if he broke the law a third time he was to be put to death. (Acts of the Parliament of Scotland, II, 13) Surely this last punishment was never carried out; but it bespoke the earnestness of parliamentary concern. Again, in 1504 it was “ordanit . . . that everilk lord and lard mak thame to have parkis with dere stankis, cunyngaris, dowcatis, orchards, heggis and plant at the leist ane aker of wod quhare thair is na greit woddis nor forestis.” (Ibid., p. 251, c.19) An Act of James II (ruled 1437-60) decreed that “freeholders cause their tenants to plant woods, trees, and hedges, and sow broom in convenient places.” (Ibid., p. 14, c.80) This act was ratified in the fourth Parhament of James V (1535), with the added stipulation that “Every man having an hundred pound land of new extent whereon there is no wood, [shall] plant wood and make hedges and haining extending to three acres, and [require] their tenants to plant for every merk land a tree under the pain of ten pounds to be paid by every laird that fails.” (Ibid., c.10) An Act of James VI (Ibid., p. 11, c.83) enacts “that wilful destroyers and cutters of growing trees be punished to death as thieves.” See also, in 1541, Royal Rentals, Exchequer Rolls of Scotland, XVII, 719.

Destruction of forests had led to the extermination of such wild animals as formerly inhabited the woods. The wild boar, once common, was scarcely seen after 1500, nor were wolves, formerly numerous and dangerous. For fuel the Lowlanders burned turf, stone peat, and coal.*

All over the Lowlands were marshes and small lochs which no longer exist. Arable areas were still further limited by the ignorance of the people about drainage. A serious drawback to decent farming was that there were no fences, hedges, or stone walls to separate farms, fields, or strips (“rigs,” as the Scots called them). All fields lay open, and even the employment of shepherds could not keep animals from straying. When a farmer’s cattle trampled the crops of another, and the second farmer retaliated, another element was added to the insecurity of life and another cause existed for ill-feeling between neighbors.

Scotland was noted in the eyes of foreigners as a barren land. Shakespeare compares it for nakedness to the palm of the hand.3 The soil in the southwest was miserable. Sir William Brereton, an Englishman who traveled from Glasgow to the southern part of Ayrshire at the very moment many of the Scots were going across to Ireland, said: “We passed through a barren and poor country, the most of it yielding neither corn [grain] nor grass; and that which yields corn is very poor, much punished with drought.”4 Only the higher portions of land were chosen for tillage. The valleys and banks of rivers were too marshy and too much exposed to sudden inundation for farming by a people who had neither the knowledge nor the industry to build dams, sluice off excess water, or prevent floods.*

* The earliest mention of the working of coal, or “blackstones,” is said to be in a charter of 1291. (Innes, Sketches of Early Scottish History, p. 235. See also Brown, Early Travellers in Scotland, p. 26.) John Major, writing in 1521, said that “heather or bog-myrtle grows in moors in greatest abundance, and for fuel is but little less serviceable than juniper.” (History of Greater Britain, p. 51)

One of the chief reasons, and possibly the primary cause, for the continued backwardness of farming methods was the insecurity of life and property; and this in turn was a corollary of the addiction of the Scots to fighting and violence. Cause and effect are here intermingled. It is the lawlessness and violence of life in Scotland throughout the period from 1400 to 1600 that made the deepest impression on visitors from more stable countries and that justify one in speaking of the life of Lowland Scotland as barbarous.

Noblemen set the example, even by their determination to defend the rights of their underlings. They took the law, what there was of it, into their own hands. They constantly feuded with one another, and the lairds† followed the lead of their overlords by feuding with other lairds. When local quarrels were quiescent, there was the constant threat of war with England, or the frequent actuality of English raids across the Scottish border, where the dividing line of the Cheviot Hills and the Tweed River interposed no true barrier. Scottish farmers formed the armies. It was a rare farmer who was not a returned soldier, and an even rarer one who had not participated in a foray with arms; thus violence was confirmed as a way of life. “In a countiy where feudalism still prevailed and where there was little general organization of justice, driving off cattle and sheep was almost one of the recognized sports of the time. You appealed to your feudal overlord to help you regain your stock; in that foray to regain what had been lost your lord and his fellow retainers were not unlikely to bring back more if possible than what had been driven away.”5

* In Scotland the laird seems to have taken little or no part in overseeing the farming methods of his tenants. Here was a great contrast to England of the time. Despite the primitiveness of English agriculture by our modern standards, one gains the impression of gradual and steady improvement of methods in late medieval times. The English farmer certainly knew how to drain his lands; security of tenure made him try to improve his lands and houses; and the surveillance of the squire was a bulwark against shoddy work and methods. (For comment on the state of farming in the Lowlands, see Mackenzie, History of Galloway, I, 229.)

† The laird is a landholder, a member of the gentry, not a nobleman. He corresponds generally to the English squire.

In those unspacious times, when even few barons could read and write,6 and before the church established by the Reformation had begun to promote education, when cities were few and roads were mere paths, people had little to occupy either the mind or the imagination. It is understandable that customs should have resembled more those of the time of Beowulf or of the tribes of central Europe during the Dark Ages than those of the present. When people are isolated, farming is monotonous and life is drab, with no visitors, no news, and little diversion. Fighting and raiding were not only traditional: they were an exciting relief from tedium.

The root of the trouble was political, for no king since the time of Robert the Bruce (d. 1329) had been able to keep the English out, or to rule over the whole country and so provide national law and order. Seven monarchs ruled between 1406 and 1625, and, of the seven, five had been infants or mere children upon their accession. Long regencies gave noblemen an opportunity for cabal, bickering, maneuver, and most of all for assertion of their independence from royal control. Scotland had no standing army, no regular taxation, no police force, and very few civil servants. Under such conditions every baron was a law unto himself.

Feudalism everywhere implied the right of noblemen to carry on their private quarrels. In this it corresponded with the clan tradition of much earlier times in Scotland.* Since barons lived in strong castles, the king was rarely powerful enough to subdue them to his rule, even if he could have persuaded other barons to fight on his side to establish a principle that would curb their own independence. Nor were the kings always wise and good

* Feudalism had been brought in by David I in the twelfth century, under the influence of the Normans living in England. Its principle of making a lord responsible for his own land and people so well accorded with clan organization that David had little trouble in introducing feudalism to Scotland.

Scotland: Highlands and Lowlands

and constructive in their policies. Noblemen regarded the king as merely another power, sometimes useful as an ally in their ambitious enterprises, but always to be made to realize that he was no better a man than they. Few felt any personal loyalty to him or any dedication to the principle of unified central authority. The national government, if it can be called such, was rule by faction.

What can be said for the lords is that most of them felt deeply responsible for the life and goods of every dweller on their domains. An unavenged injury to any person or thing, however indirectly connected with the lord, was at once a personal insult and a derogation from his authority. If he could not defend those who looked to him for protection, the very reason for his existence was at an end.7 It must be said, too, that a lord’s protection was really valuable to his people in the unpoliced land; without it the tenant would have been helpless. But one man’s security was another man’s insecurity; one raid led to another in endless succession. Parliament took constant note of the rapine, spoil, and lawlessness,8 yet the very barons who composed the Parliament refused to apply the Acts to themselves and submit to restriction.

The other side of the picture is that the lords were often as unprincipled as they were rank individualists. A modern historian calls them “as brutal tyrants as ever lived.”9 Thomas Carlyle, himself a Scot, made the “swingeing generalization” about them that they were “a selfish, ferocious, unprincipled set of hyenas.”10 The author of the anonymous Complaynt of Scot-lande in the sixteenth century made Dame Scotia bitterly reproach her noblemen, saying: “Thou are the special cause of my reuyne, for thou and thy sect that professes you to be nobilis ande gentill men, there is nocht ane sperk of nobilnes nor gentrice among the maist part of you.”11

Feuds were not only traditionally customary but in contemporary minds were justifiable. Sicily’s vendettas had their counterpart all over Scotland. In the southwest, especially, these blood feuds were violent and unending. Montgomery and Cunningham were the Montague and Capulet of Ayrshire, if the Kennedys and their opponents could not contest the designation. Since the Crown was not strong enough to put down the rivals, it stood aside and let them fight it out.12 One historian names a list of families who “lived in a great measure by robbing and oppressing their neighbors. Occasionally, too, they would make predatory forays into England, and thereby endanger the peace existing between the two realms.”13 The Records of the Privy Council are full of instances of assaults made by men of rank and property with deadly weapons. Despite Acts of Parliament prohibiting going about armed defensively or offensively, men still “set about their vengeful proceedings in steel bonnets, gauntlets, and plait sleeves, and with swords and pistolets.”14 The traveler John Major attributes much of the violence to pride, for “among the Scots ’tis held to be a base man’s part to die in his bed, but death in battle they think a noble thing.”15

Emissaries from the king who tried to enforce the law were often handled summarily. Letters and summons were taken from officers and torn to tatters, and once an officer was made to eat and swallow the summons he bore. “Evildoers boasted, menaced, disobeyed, struck, and pursued the officers, and sometimes killed them outright.” The officers themselves were peccant, sometimes taking bribes from the rich and powerful.16

The most constant crime, more likely than the feuds of noblemen and lairds to keep the farmers in a turmoil, was cattle stealing.* Theft of stock often led to assault, and assault to a general fight to the death. This private avenging of wrong, combined with the feuds, makes it seem that Scotland was in a constant state of undeclared civil war. Tenants of those lords who got the worst of any of the frequent broils suffered severely, and the lot of men living upon the land of a freeholder who was not strong enough to defend them must have been a hard one.†

* This achieved the dignity of a special term, “hership” or “herdship,” which Hume (Commentaries on the Laws of Scotland, I, 126) defines as “the driving away of numbers of cattle, or other bestial, by the masterful force of armed people.”

† The violence of the country can be seen from the types of law cases. John Hill Burton (in his preface to the Register of the Privy Council, II, xxiii) notes the prevalence of the arrangement of pacts of guarantee and suretyship for the preservation of the peace, and comments that they convey “the impression of a turbulent people, likely to suffer from each other’s violent propensities.” He refers to such actions as “spuilzie,” whereby redress was sought for violent or wrongful taking away of movable property; ’assythments” and “letters of slains,” devices to prevent violent reprisals for wrongs already committed; and “law-burrows,” or surety to prevent feuds and troubles. See Register of the Privy Council, VI (1599-1604), 609-660; Acts of the Lords of the Council in Secret Causes, I, lxix-lxx; and Grant, Social and Economic Development, p. 191.

Added to all this, there were the constant wars between England and Scotland, generally fought on Lowland territory, and usually accompanied by the burning of crops and other property. Englishmen of Cumberland and Northumberland, the counties adjacent to the Lowlands, were not above making their own raids across the border. Between 1377 and 1550 “there was either tacit or open war between Scotland and England during fifty-two years;”17 moreover, when there was not actual fighting, the truces were precarious. Life on the Border was notoriously unsafe. At least until the Reformation, travel was dangerous anywhere in Scotland ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- THE SCOTCH-IRISH A Social History

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Contents

- Maps

- Introduction

- PART I: THE SCOT IN 1600

- PART II: THE SCOTS IN IRELAND

- PART III: THE SCOTCH-IRISH IN AMERICA

- APPENDIX I The Name “Scotch-Irish”

- APPENDIX II Important Events in Scottish History

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index