eBook - ePub

A Death Retold

Jesica Santillan, the Bungled Transplant, and Paradoxes of Medical Citizenship

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Death Retold

Jesica Santillan, the Bungled Transplant, and Paradoxes of Medical Citizenship

About this book

In February 2003, an undocumented immigrant teen from Mexico lay dying in a prominent American hospital due to a stunning medical oversight — she had received a heart-lung transplantation of the wrong blood type. In the following weeks, Jesica Santillan’s tragedy became a portal into the complexities of American medicine, prompting contentious debate about new patterns and old problems in immigration, the hidden epidemic of medical error, the lines separating transplant “haves” from “have-nots,” the right to sue, and the challenges posed by “foreigners” crossing borders for medical care.

This volume draws together experts in history, sociology, medical ethics, communication and immigration studies, transplant surgery, anthropology, and health law to understand the dramatic events, the major players, and the core issues at stake. Contributors view the Santillan story as a morality tale: about the conflicting values underpinning American health care; about the politics of transplant medicine; about how a nation debates deservedness, justice, and second chances; and about the global dilemmas of medical tourism and citizenship.

Contributors:

Charles Bosk, University of Pennsylvania

Leo R. Chavez, University of California, Irvine

Richard Cook, University of Chicago

Thomas Diflo, New York University Medical Center

Jason Eberl, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis

Jed Adam Gross, Yale University

Jacklyn Habib, American Association of Retired Persons

Tyler R. Harrison, Purdue University

Beatrix Hoffman, Northern Illinois University

Nancy M. P. King, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Barron Lerner, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Susan E. Lederer, Yale University

Julie Livingston, Rutgers University

Eric M. Meslin, Indiana University School of Medicine and Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis

Susan E. Morgan, Purdue University

Nancy Scheper-Hughes, University of California, Berkeley

Rosamond Rhodes, Mount Sinai School of Medicine and The Graduate Center, City University of New York

Carolyn Rouse, Princeton University

Karen Salmon, New England School of Law

Lesley Sharp, Barnard and Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Lisa Volk Chewning, Rutgers University

Keith Wailoo, Rutgers University

This volume draws together experts in history, sociology, medical ethics, communication and immigration studies, transplant surgery, anthropology, and health law to understand the dramatic events, the major players, and the core issues at stake. Contributors view the Santillan story as a morality tale: about the conflicting values underpinning American health care; about the politics of transplant medicine; about how a nation debates deservedness, justice, and second chances; and about the global dilemmas of medical tourism and citizenship.

Contributors:

Charles Bosk, University of Pennsylvania

Leo R. Chavez, University of California, Irvine

Richard Cook, University of Chicago

Thomas Diflo, New York University Medical Center

Jason Eberl, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis

Jed Adam Gross, Yale University

Jacklyn Habib, American Association of Retired Persons

Tyler R. Harrison, Purdue University

Beatrix Hoffman, Northern Illinois University

Nancy M. P. King, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Barron Lerner, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Susan E. Lederer, Yale University

Julie Livingston, Rutgers University

Eric M. Meslin, Indiana University School of Medicine and Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis

Susan E. Morgan, Purdue University

Nancy Scheper-Hughes, University of California, Berkeley

Rosamond Rhodes, Mount Sinai School of Medicine and The Graduate Center, City University of New York

Carolyn Rouse, Princeton University

Karen Salmon, New England School of Law

Lesley Sharp, Barnard and Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Lisa Volk Chewning, Rutgers University

Keith Wailoo, Rutgers University

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1: Medical Error and the American Transplant Theater

Chapter 1: America’s Angel or Thieving Immigrant?

Media Coverage, the Santillan Story, and Publicized Ambivalence Toward Donation and Transplantation

Organ donation has always faced a difficult battle in vying for positive media coverage. At the center of key tensions over how we tend to think about the goals of modern medicine and how we think about the human body, organ donation has often produced a profound ambivalence. Historically, print journalism and television coverage has often utilized almost Frankenstein-like images of “harvesting” organs to rebuild a defective human body while, at the same time, portraying organ transplants as miracles of modern science and the sole hope for life for the many thousands of people on the waiting list. Jesica Santillan’s so-called botched transplant generated an intense media attention from February to March of 2003 that reflected this deep-seated ambivalence. News coverage first centered on a report of the clinical story: a terrible error and a failure to double-check medical tests lead to the near-death of a young Mexican girl at Duke University Medical Center in North Carolina. However, when a new set of organs became available almost immediately, the coverage began to question the fairness of the organ allocation system: how were doctors able to procure organs so quickly when thousands of other patients were waiting? These stories and commentary soon turned to ugly questions about why organs from an American citizen were used to save the life of an undocumented immigrant when so many American citizens were dying while waiting for transplants. In its slow transformation from a story of lifesaving transplant surgery into a vexing scandal laden with blame and accusation, the Jesica Santillan case added to the corpus of mixed messages in the media and throughout America about organ and tissue transplantation.

This essay examines shifts in media representations as the Santillan story unfolded in national and local media. We do not tackle critical questions about the motivations that shape these representations, nor are we interested in variations in how various newspapers and television stations across the United States covered the story. Rather, in the following pages we elucidate the overarching narrative of the Santillan transplant, how the story emerged into the public sphere, how it changed over time, and how authors and commentators articulated the meaning of this case. On such high-tech medical and scientific topics, Americans tend to rely heavily on representations in national media, especially because most readers have little personal experience with the issues; in these instances, then, such accounts play a disproportionately powerful role in shaping opinions.1 Therefore, a national examination of the Santillan coverage provides a crucial starting point for understanding how key characters in the drama were presented to most Americans, and how these characters themselves came to embody different features of the publicized ambivalence toward organ donation and transplantation. Moreover, this national examination also allows us to follow the rapid shifts, instabilities, and ambivalences in the public discussion not only of the Santillan drama and organ donation and transplantation, but also of immigration—a theme that became a potent backdrop of the public commentary (see figure 1).

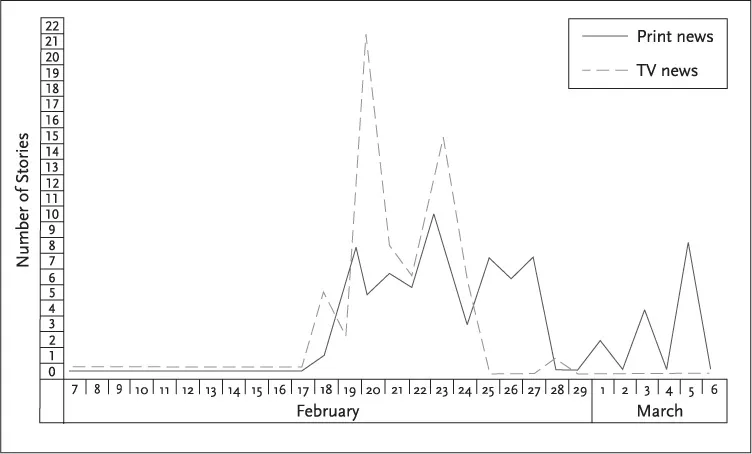

Remarkable events associated with a particular phenomenon create a spike in media coverage, and they also create potential turning points in representations of the phenomena.2 The case of Jesica Santillan represented exactly such an extraordinary event that brought to the surface of public discussion deeper conflicts about donation and transplantation. While many other cases of organ donation have captured public attention for a few days at a time, in this instance media coverage lasted much longer than one or two days. The most intense reporting spanned approximately two weeks, from February 17 to March 5, 2003 (see figure 2); but articles referencing Jesica Santillan could still be found six months later. We used a television monitoring service called ShadowTV to gather data on this coverage, and we also performed routine online searches for national and regional newspapers stories. We focused principally on coverage of Jesica’s story after the initial transplant on February 7. As a media event, the story was nevertheless shortlived, beginning with intense reporting on February 17 after the public disclosure of the error. By February 28, virtually all television coverage ended whereas heavy print coverage continued until March 27, 2003. Overall, our research uncovered 97 unique print stories and 65 unique television stories that featured or referenced the Jesica Santillan case, resulting in 162 stories for analysis.3

What were the major recurring patterns of coverage? And how did the themes (and the intensity of coverage) change over time? The telling of the Santillan story produced a wide range of prototypical images of Jesica, her family (particularly her mother Magdalena), her patron Mack Mahoney, Duke University and its spokespeople, and other key actors such as the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), and the coverage also produced linguistic themes that anchored the story. In the creation of social representation, processes of anchoring (that is, finding language to describe the new phenomenon) and objectification (in which key concrete images or prototypes are attached to the phenomenon) are crucial.4 Over time, despite internal contradictions in the news reporting and commentary, despite wide variations in how the story was told in different parts of the country, and despite large differences between television and print media, a “consensual reality” of the case took shape.5 A number of actors appeared repeatedly in news coverage, and as their influence on the circumstances changed, so did the media’s portrayal of those individuals.

MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF JESICA SANTILLAN

The Santillan case played out like a drama in which media portrayals of concealment, deception, power, moments of joy, and tragedy captured the attention of the public. Yet, despite most of the action, the central actor, Jesica Santillan, was a silent symbol, characterized either as a victim/saint or, conversely, as an illegal immigrant. She would not be presented as a full person until after her death.

When television and print media first introduced their readers and listeners to Jesica in a comprehensive way, she had already undergone the first transplant with mismatched organs almost ten days earlier, and lay in critical condition. A second transplant offered her only chance for survival. While her family and her advocate Mack Mahoney petitioned the public for help saving Jesica’s life, doctors contended that there was little that could be done. Jesica was small, frail, and barely clinging to life; and she was surrounded by a desperate family, apologetic doctors, and a chastened hospital. In one account after another, media accounts implicitly invited the public to pray along with Jesica’s family. And when Jesica received the second transplants on February 20, her family and friends were portrayed as happy and grateful. At the same time, however, the coverage that had encouraged communal hope, began to question why a frail patient with such a slim chance of survival had received another transplant. Part of the explanation was the “sickest first” policy that determined eligibility; and Jesica clearly had become—because of her body’s rejection of the first set of organs—extraordinarily ill. As ethicists and legal experts debated the wisdom of the “sickest first” allocation system and while others wondered why an illegal immigrant received a transplant in the first place, within days of the second transplant the story of Jesica Santillan was becoming more complex.

Figure 1. Timeline of Jesica Santillan Events and Media Coverage Turning Points

While, for some, Jesica became the face of an important issue—the shortage of organs for children—she was also described as an unfortunate example of the toll of errors in cutting-edge medicine. But in the wake of the second transplant, her case would also become a potent immigration narrative. The media embraced Jesica through the well-trod narrative of immigrants chasing after the hope of a better life in America. A great deal of action—both real and symbolic—occurred around Jesica, and yet, because of the nature of her condition, she actually said and did the least in these news accounts. The lack of reportable action, then, left readers dependent on the various media attributions to link particular motives, sentiments, and feelings to Jesica. Where other characters might be allowed to speak for themselves, these actors in the drama (and the writers of the various news accounts) also spoke for Jesica in the unfolding media coverage.

Figure 2. Intensity of Media Coverage over Time (Number of Stories by Date)

Initially, accounts described Jesica in various and often conflicted ways. Some saw her as a seventeen-year-old, desperately ill patient with a grave prognosis. Others characterized her as a “botched transplant victim,” and drew attention to her status as a poor, small-town girl. Elsewhere, Jesica was referred to as a “baby [that] needed some help,” echoing her mother’s characterizations, and some media stories further embellished her profile as the “world’s sweetheart.”6 As Nancy King and Carolyn Rouse point out elsewhere in this volume, the media was drawn to her as a “mediagenic” individual—and these accounts quickly cast her as a young, pretty, “innocent,” and sympathetic figure. The combination generally evoked positive public reactions.

At the same time, however, news stories rarely failed to mention her immigration status—albeit in various ways. Jesica was described as a “Mexican teenager,” a characterization that eventually morphed into “Mexican immigrant,” and later (by the end of the two-week period) into an “illegal immigrant from Mexico.” The transformation in terminology reveals much about the shifting public meaning of the case. The “illegal immigrant” characterization invigorated controversy, for it shifted attention away from error and Jesica’s victimization to her impropriety—put bluntly, to the question of whether an illegal immigrant should be allowed to receive transplants in the United States. As Beatrix Hoffman and Leo Chavez note elsewhere in this volume, long-standing concerns about immigrants’ rights to health care shaped these public reactions to Jesica’s case. And as we see in Jed Gross’s essay, these anxieties could also emerge around cases of wealthy foreigners purchasing access to transplants in America. In such cases, immigration anxieties often commingled with barely submerged public mistrust about the allocation system.

Media claims of public outrage over Jesica’s transplants peaked after her death, and a great deal of animus centered on claims of theft—or (as articulated by one college newspaper) that Jesica “[came] into our country and [took] the organs of not one, but two people, that could have gone to more deserving Americans.”7 By late February into early March, the tone of coverage had become inverted in crucial ways. When, early on after the first transplant, the outlook for Jesica had been most grim, stories cast her as an innocent victim; yet, just when events took a positive turn and Jesica received matched organs, questions of privilege and special consideration emerged. As her condition changed yet again and as her health declined, these conflicted characterizations would continue.

The often hyperbolic images of Jesica in the amalgam of news coverage traversed a spectrum between thieving immigrant and martyred saint. In the most vitriolic description, a caller to a radio show in the Southwest labeled her as a “wetback” immigrant who took organs from dying Americans.8 On CNN, on the other hand, she was called “America’s sweetheart” who had touched the hearts of many.9 These images, of course, had little to do with Jesica herself, and much to do with popular American, even mythic, representations: the innocent victim, the underdog fighting the heartless system, on the one hand; and, on the other, the despised lawless outsider using precious resources intended for others, her greed resulting in the death of others.

PORTRAYING THE SANTILLAN FAMILY

In many respects, it was Jesica’s family who bore the brunt of this characterization as conniving thieves (as we shall see later), but they themselves also played a role in shaping the public imagery of the case. The first days of media coverage saw the family’s first appearance. The Santillan family spoke little English. Through a translator, they called the mistake “unforgivable,” but Jesica’s mother and father remained focused on obtaining a new transplant.10 Their grief was evident but so too were the spontaneous bouts of anger toward the doctors and hospital. For example, when they called Duke Medical Center “piranhas,” they evoked predatory and even vampiric images that had long circulated in social representations of organ donation and transplantation. The family’s pronouncements in the media captured much about the public’s sentiments about medicine and error. Magdalena Santillan, Jesica’s mother, was reported stating bluntly that the “doctor should go to jail,” and yet other stories showed her pleading for anyone concerned or anyone with a dying child whose organs might be available to help her find “the organs that my daughter needs to live.”11

The Santillan family’s direct appeal for public support and organs to save Jesica would have lasting implications. It foregrounded into public view another notion that had long been associated with transplantation: that public pressure, backroom deals, and the special status of patients were crucial factors in determining who received organ transplants. When Jesica received the second transplant days later, her mother’s expression of gratitude to both the donor family and the media reinforced these sentiments. Magdalena suggested (and one CNN story translated her words) that “if it hadn’t been for the support from . . . TV, from radios and newspapers . . . they would have let my baby die. I’ve seen a lot of cases where they don’t pay much attention to Latinos.”12 But at the same time, Magdalena was also reported to have said that doctors had now done all they could.13 And in the days after the second transplant, as Jesica’s health began to deteriorate, the Santillan family receded from most news accounts.

But throughout the ordeal, the family’s voices were often complemented by other actors who spoke for them. As the news commentary expanded, indeed more and more figures became involved in representing the family. There was, for example, the ever-presen...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- A Death Retold

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Medical Error and the American Transplant Theater

- Part 2: Justice and Second Chances Across the Border

- Part 3: Citizens and Foreigners/Eligibility and Exclusion

- Part 4: Speaking for Jesica

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Death Retold by Keith Wailoo, Julie Livingston, Peter Guarnaccia, Keith Wailoo,Julie Livingston,Peter Guarnaccia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Ethics in Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.