![]()

Chapter One: Dissident Democrats in the 1830s

William Leggett, George Henry Evans, and Thomas Morris

As Andrew Jackson delivered his farewell address in 1837, the Democratic Party was at its apex. Even though the president, less than two weeks shy of his seventieth birthday, railed passionately against the Second Bank of the United States and privileged men who meet in “special conclaves” to buy and sell elections, most Jacksonians agreed that the dreaded Money Power was in retreat. The bank’s charter, after all, had expired in 1836, making Nicholas Biddle’s “monster” just another private bank headquartered in Philadelphia. The $5 million federal surplus had been returned to the states, and Jackson’s Specie Circular, Democrats believed, weakened the dangerous power exercised by speculators on the frontier. There were other reasons for optimism as well. Jackson’s handpicked successor, Martin Van Buren, had won a majority of the popular vote and 58 percent of the votes in the electoral college, capturing states in every region of the country. More important, the opposition was hopelessly divided: three Whig candidates had combined to win just ten states in 1836, while the Democracy appeared to most observers to be united and strong.

Yet rumblings of discontent could be heard throughout the victorious party. Some western Democrats questioned the wisdom of Jackson’s hard-money policy on land sales, and others feared that the “pet” banks that succeeded the Bank of the United States would be unable to coordinate monetary policy for Jackson’s successor. And, perhaps surprisingly, a few Democrats objected loudly to the party’s popular positions on slavery. Such objections were both isolated and rare, and the party’s policies of banning abolitionist material from the mail and tabling every antislavery petition sent to Congress remained in effect, robbing abolitionists of their Constitutional freedom to speak publicly. Democratic chieftains at the highest levels helped enforce “the correct state of public opinion” by cheering on mobs that attacked abolitionist meetings and newspapers.1 But discontent within the party over the gag rule, mail violations, and the treatment of abolitionists by angry mobs—though muted—solidified into arguments to counteract slavery’s expansion that would become important in later decades. This chapter will focus on three antislavery Democrats who broke with the party in the 1830s, well before the debate over slavery extension prompted the Free Soil schism in the 1840s and 1850s. Significantly, each of these early dissidents arrived at his antislavery position as a result of battles over abolitionism in the North, and not over the issue of slavery in the territories—the issue that swelled the movement in the decades before the Civil War. More important for the argument advanced in this study, early dissidents provided specific lines of argument that would later help galvanize and significantly expand the Free Soil movement.

Ohio senator Thomas Morris, for example—the first senator from either party to defend abolitionists on the floor of the U.S. Capitol—formulated and popularized the concept of a Slave Power. The term quickly came to encompass the entire range of anxieties and hostilities northerners harbored toward slavery and the South, and for many antislavery Jacksonians it replaced the Money Power as a master symbol for the aristocracy’s ascendance. New York editor William Leggett, who eventually came out as a full-fledged abolitionist, fashioned compelling antislavery arguments from his pro-producer and antimonopoly views, making him a hero to many Free Soilers. George Henry Evans—a freethinker, mechanic, editor, and land reformer—set in motion a reform movement over the future settlement of the public lands that brought two fundamental tenets of Jacksonian ideology (universal landownership and protection of slavery within a disciplined, national coalition) into irreconcilable conflict.

During the 1840s and 1850s, the arguments set forth earlier by Jacksonians such as Leggett, Morris, and Evans were to be amplified by external events such as Texas annexation, the Mexican War, and the Wilmot Proviso. These arguments, compounded by the increasingly aggressive actions of their onetime proslavery brethren, persuaded a growing number of northern Democrats that the South could no longer be trusted as a political ally. When they came to believe their party was in the hands of a proslavery conspiracy, they quit—and laid down arguments that would cause much larger defections in the years to come. These Democrats formed the backbone of the Free Soil coalition that helped bring an end to the second party system.

William Leggett

No other Jacksonian, however prolific or zealous, could match William Leggett’s eloquence in articulating arguments against centralized authority, whether embodied by monopolies, “fanatical” reformers, or the Money Power. Leggett’s writings for the New York Evening Post and his own Plaindealer are among the most polemical and memorable of the antebellum era, each editorial laying the intellectual groundwork for the system of antimonopoly, hard-money, and free-trade beliefs that came to be known as Locofoco egalitarianism. Leggett’s arguments against concentrated power in any form, grounded firmly in concepts of natural law and liberty, led him first to champion the classes of producers over capitalist enterprise, making him a hero to the Democratic Party’s labor wing. When he applied this same reasoning to slavery in the mid-1830s, the former antiabolitionist underwent a conversion so absolute and unexpected that it took him beyond the stance of most Garrisonians to a passionate advocacy of racial equality. Leggett thus pushed both Democratic egalitarianism and antislavery to their outer limits, confirming Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s description of him as “the Democrat in whom social radicalism and antislavery united most impressively.”2

Leggett’s formidable hostility to centralized authority began in his youth. In 1825, at age twenty-four, he was court-martialed out of the navy for insulting his commanding officer with, among other things, “abusive verses” from Lord Byron.3 Yet his naval career, disastrous as it was, provided the young writer with material for Leisure Hours at Sea, a volume teeming with wrenching scenes of captains’ wanton authority visited upon innocent sailors. At least one reviewer of the work made a connection between life on a ship and on a plantation: “After reading this book and reflecting on its subject, we came to the conclusion that to be master of one of our [naval] vessels is very much like being a negro driver, and to be a ship owner very much like being a slave holder.”4 In “The Squatter: A Tale of Illinois,” Leggett moved onto dry land and confronted directly the issue of race. Unlike his other stories, which feature black characters only in supporting roles and contain abundant racist stereotypes, “The Squatter” places Mungo, an elderly black servant, in the role of protagonist. One of Leggett’s techniques in the story is to contrast Mungo’s shrewdness and humanity with the white characters’ ignorance, expedience, and bigotry (one white character calls Mungo “that cursed piece of Indian ink”). Intentionally or not, by making Mungo’s intelligence and decency invisible to his white “superiors,” Leggett effectively undermines their racism and gives his story an unlikely hero. Like his earlier attempts at poetry, Leggett’s stories were critical and popular failures. But his sympathy for the downtrodden, be they despised slaves, luckless squatters, or terrorized sailors, was emerging as a recurring theme in his writings.5

Literary failures or not, Leggett’s fiction attracted the attention of William Cullen Bryant, the owner of the Democratic New York Evening Post. Bryant invited the young author to write literature and theater reviews for the paper in June 1829; Leggett accepted on the express condition that he would not be asked to write about politics. This arrangement was apparently temporary, for Leggett’s first political editorials—sparkling with a wit and eloquence absent in his earlier attempts at fiction and criticism—appeared two months later.6

Leggett’s political writing has been dissected in print many times. Conservative diarist Philip Hone commented that Leggett “disgraced the once respectable columns” of the Evening Post “by the most profligate and disorganizing sentiments. This unblushing miscreant makes himself popular … by administering to the vitiated appetites of his fellow men nauseous doses of personal slander.” A century later, Richard Hofstadter had reduced the “unblushing miscreant” to a “bourgeois radical.” Although he never delved into Leggett’s antislavery writing, Marvin Meyers was closer to the mark in pointing out that each of Leggett’s editorials centers on concern for both rights and power.7 These two concepts were at the root of his developing worldview: Leggett saw the potential of corrupt central authority everywhere, from the seemingly innocuous functioning of state charities to the delivery of the mail in rural areas (which, he argued, fattened political machines with patronage and encouraged rapid settlement in remote places, thus benefiting speculators).8 What truly distinguished the young scribe, however, were his relentless attacks on the Money Power, the interlocking collection of financial institutions and capitalists that, he asserted repeatedly, preyed on the labor of farmers and laborers. His editorials, picked up by Democratic papers throughout the country during the 1830s, solidified the Post’s position as the party’s leading organ in the nation’s leading city.

The “banking system,” Leggett wrote in 1834, “is essentially an aristocratic institution [that] bands the wealthy together, holds out to them a common motive, animates them with a common sentiment, and inflates their vanity with notions of superior power and greatness.” Idle bankers made their money, he explained in his merciless editorials, out of the hard earnings of poor people and funneled political as well as monetary power to the rich. This concentration of “exclusive money privileges” was, according to Leggett, in “direct opposition to the spirit of our constitution and the genius of the people. Unless the whole system be changed, [the rich] will rise in triumph on the ruins of democracy.”9

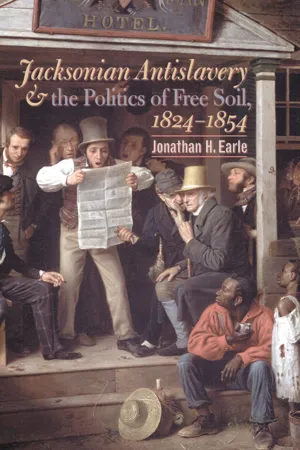

FIGURE 3

William Leggett (1801–1839). The intellectual Leggett, a leading Democratic editor in the 1830s, pushed Jacksonian egalitarianism and then Jacksonian antislavery to their outer limits. His ideas were adopted by antislavery Democrats and Free Soilers throughout the antebellum period. (Library of Congress)

Despite their reddish tinge of class warfare, Leggett’s editorials on free trade, banking, and monopolies generally supported the Jackson administration’s policies, and Bryant felt confident enough in his young partner (Leggett used a loan to buy a half share in the paper in 1831) to leave him in charge when he left for a tour of Europe in 1834.10 Bryant had been gone barely two weeks when antiabolitionist mobs attacked antislavery meetings and black homes and churches in the “July Days” riots, beginning Leggett’s yearlong, zigzagging conversion to abolitionism. For three days, rioters ruled the streets of Manhattan, destroying more than sixty dwellings, wrecking at least six churches, and causing untold personal injuries.11 Although at the time he called abolitionism a “scheme” designed to promote the “promiscuous intermarriage of the two races,” Leggett could not see how their meeting “furnish[ed] … justification for invading the undoubted rights of the blacks, or violating the public peace.”12

As one looks back on Leggett’s “preconversion” editorials attacking abolitionists as “fanatics” (a virtual synonym for abolitionists in both the Democratic and Whig presses), it is clear that he was most anxious about the danger mobs posed to the rights of free discussion guaranteed by the Constitution. Later, the increasingly repressive tactics employed by southern politicians to silence their abolitionist critics (such as the gag rule and the banning of abolitionist material from the mails) pushed Leggett even further toward the antislavery position. Eventually, he decided the slave system itself was the wellspring of a growing wave of southern-led assaults on the nation’s founding document. “Not only are we told that slavery is no evil,” he wrote in 1835, but that it was a “violation of the spirit of the federal compact, to indulge even a hope that the chains of the captive” may one day be broken. Next, he joked, the “arrogant south” would call upon northerners to “pass edicts forbidding men to think on the subject of slavery,” on the ground that even meditation on the topic violated the spirit of the Constitution.13

When the southern states’ rights faction of the Democratic Party, led by Governor George McDuffie, attacked northern supporters of Martin Van Buren as “pro-abolitionist,” Leggett was stunned. As he familiarized himself with antislavery literature during the mid-1830s, he gradually stopped insulting abolitionists as “amalgamators” and instead described them as “men of wealth, education, respectability and intelligence, misguided on a single subject, but actuated by a sincere desire to promote the welfare of their kind.”14

A particularly violent antiabolitionist mob in Haverhill, Massachusetts, finally brought about Leggett’s heretical conversion. In a scene that bore a chilling resemblance to the previous summer’s riots in New York, a large mob dragging a loaded cannon and carrying other explosives marched on an abolitionist meetinghouse. Leggett again claimed that such attacks would only fortify the abolitionists; this time, however, he warned that blood shed in the battle against slavery threatened to “engender a brood of serpents which shall entwine themselves around the monster slavery, and crush it in their sinewy folds.” With this editorial, the “monster slavery” replaced in Leggett’s mind monopolies and the “scrip nobility” as the most serious aristocratic threat facing the nation’s democratic institutions. The next evening, Leggett shocked Jacksonian New York by announcing he had read and almost wholly endorsed the program of the immediatist American Antislavery Society.15

According to abolitionist lore popularized by John Greenleaf Whittier, Leggett’s conversion hit him like a bolt of lightning after he read the Antislavery Society’s Address on September 3, 1835. “He gave it his candid perusal, weighed its arguments, compared its doctrines with those of the foundation of his political faith,” Whittier wrote, “and rose up from its examination an abolitionist.”16 Actually, some time elapsed before Leggett would call himself an abolitionist, with all the overtones of middle-class reform and perfectionist zeal that the term implied. In the months after his conversion to antislavery, in fact, the editor insisted he was nothing more than a particularly dedicated Jacksonian Democrat. Leggett bristled at accusations from other Democratic presses that his antislavery pronouncements meant that he had deserted his party; editorials on topics other than slavery bore him out on this point. For example, Leggett enthusiastically endorsed Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s handpicked successor, in 1835 and marked the passing...