eBook - ePub

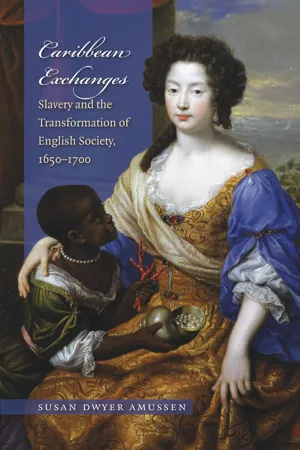

Caribbean Exchanges

Slavery and the Transformation of English Society, 1640-1700

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

English colonial expansion in the Caribbean was more than a matter of migration and trade. It was also a source of social and cultural change within England. Finding evidence of cultural exchange between England and the Caribbean as early as the seventeenth century, Susan Dwyer Amussen uncovers the learned practice of slaveholding.

As English colonists in the Caribbean quickly became large-scale slaveholders, they established new organizations of labor, new uses of authority, new laws, and new modes of violence, punishment, and repression in order to manage slaves. Concentrating on Barbados and Jamaica, England’s two most important colonies, Amussen looks at cultural exports that affected the development of race, gender, labor, and class as categories of legal and social identity in England. Concepts of law and punishment in the Caribbean provided a model for expanded definitions of crime in England; the organization of sugar factories served as a model for early industrialization; and the construction of the “white woman” in the Caribbean contributed to changing notions of “ladyhood” in England. As Amussen demonstrates, the cultural changes necessary for settling the Caribbean became an important, though uncounted, colonial export.

As English colonists in the Caribbean quickly became large-scale slaveholders, they established new organizations of labor, new uses of authority, new laws, and new modes of violence, punishment, and repression in order to manage slaves. Concentrating on Barbados and Jamaica, England’s two most important colonies, Amussen looks at cultural exports that affected the development of race, gender, labor, and class as categories of legal and social identity in England. Concepts of law and punishment in the Caribbean provided a model for expanded definitions of crime in England; the organization of sugar factories served as a model for early industrialization; and the construction of the “white woman” in the Caribbean contributed to changing notions of “ladyhood” in England. As Amussen demonstrates, the cultural changes necessary for settling the Caribbean became an important, though uncounted, colonial export.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Caribbean Exchanges by Susan Dwyer Amussen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1: Trade & Settlement

England and the World in the Seventeenth Century

They which go down to the sea in ships, and occupy by the great waters, they see the works of the Lord and his wonders in the deep. RICHARD HAKLUYT, quoting Psalm 107, in Dedicatory Epistle to Voyages and Discoveries (1589)

The English who ventured to the Caribbean built on English social forms to create new societies. Those societies emerged in a strange environment where the English encountered indigenous people while they brought Europeans and Africans to settle. As they responded to rapidly changing economic opportunities as well as social and political conditions, they built on English traditions and ways of thinking about the world and its peoples. To understand the society they constructed, we must first look at the society they came from. The English, whether propertied adventurers or poor and desperate, arrived in the Caribbean with assumptions about how societies should be ordered, what could be expected of peoples from other societies, and the purposes of colonization. Together these ideas shaped their initial experiments and the social order they created.

England in the Early Seventeenth Century

English society in the seventeenth century was marked by rapid growth of population and increasing social polarization. The population doubled between 1540 and 1640. The rising demand for food brought prosperity to those who owned arable land but impoverishment to those who did not. English agriculture became increasingly productive with the enclosure of common fields and the adoption of new crop rotations. The combination of expanding productivity and a growing population led to structural under-and unemployment: those who worked for wages found it more difficult to find work, while they paid more for food. Many English officials were concerned about overpopulation, and as late as the 1620s there were still occasional years of severe dearth, when small harvests and high prices caused widespread hunger. The vagrants who traveled the country seeking work were seen as threats to social order. For both projectors and officials, settler colonies were a solution to the problem of vagrancy and overpopulation.1

The increasing profitability of agriculture created not only unemployment at home but also surplus capital for investment, especially in trading ventures in Europe and eventually the colonies. Merchants first attempted to strengthen England’s position as a trading nation in Europe by maximizing the profits of the cloth trade. Although these efforts were unsuccessful, they signaled England’s growing engagement in the European economy and reinforced the emerging political importance of commerce. For England, as for other European nations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the first and always most important purpose of colonies was to provide the mother country with valuable products to trade on the European market. Tobacco, and increasingly from the 1650s, sugar, served as leading products for English merchants reexporting colonial products. This approach to trade was a success: by 1700 colonial goods accounted for 34 percent of imports to England, and 45 percent of exports were reexports. Over time, English manufacturers and merchants also came to depend on the export of English goods to the colonies. All of these developments—in both European and colonial trade—contributed to England’s increasing consumption of material products. More and more people in England consumed goods they did not produce—from food and drink to cloth and furniture. This “consumer revolution” gave many people a stake in England’s colonies and their produce.2

It is a mistake to think of such exchanges entirely in terms of goods; people traveled with their values and expectations. The English people who migrated to the colonies had varied attitudes toward work, which had profound effects on their experiences in settling the “new world.” On the one hand, the English shared with other Protestants a belief in the dignity of all “callings,” work in the world that glorified God. On the other hand, not everyone was expected to have the same calling; status and skills differed. Hard work at whatever calling—whether as a landowner who managed property or a laborer who worked for him—was considered a sign of virtue. Yet manual work always had less status than work of the mind. In the 1570s Sir Thomas Smith defined those who did not work with their hands—lawyers and clergy, for instance—as “gentlemen.” All women were expected to work: wives of farmers, tradesmen, and gentlemen managed the household and its many productive tasks; servant women and poor women did a wide range of domestic and industrial work and, in times of harvest, toiled in the fields alongside men. Even the wives of gentlemen and nobles carried out and supervised their households’ domestic economies and in some cases provided medical care in the wider community. The work of the housewife, whatever labor was entailed, was a sign of her virtue: she was paying attention to her household rather than seeking pleasure.3

The issue of who worked, and who did what kind of work, became a persistent challenge in the Caribbean. Some of the early settlers in Barbados, as in Virginia, came from gentry families and were unwilling to work with their hands. But even men who would have expected to work in England assumed they would have an easier life in lands that promised quick riches. The gradual establishment of a system of labor based on slavery did not end disputes over status or work among the English.

English society in the seventeenth century was hierarchical. The hierarchy was rooted in the household, which was ruled, at least in theory, by a benevolent father; the household served as a mirror of the state, ruled by a beneficent king. In the context of the household, subordination was a function of age as much as status. One of the primary forms of education and training was “service,” living as a servant or apprentice in another household. Almost everyone in English society spent some part of their youth away from their parents’ home in such service. While those in service were bound by contractual obligations to their masters, they were in other ways free—able to testify in court, for instance, or enter into marriage. Most people moved from service to a position of greater independence when they married. For women, marriage and maternity signified social adulthood. For men, independence was a precondition for the full membership in civil society: independence required ownership of property or a business, as well as the establishment of a family and household. Those who did not have property left service when they married and worked for wages as laborers.4

While servants might be exploited and abused, they were protected by the observation of neighbors and by law. Indeed, one of the notable characteristics of English society in this period was the ideological role of law and the law’s purview across all social relations. The legal system required the participation of many people of various social ranks. In each English county, quarter sessions met four times a year to try criminal cases. While the largest landowners, as justices of the peace, had the most power, many others had important roles, serving on grand and petty juries and appearing as witnesses to crimes or as constables, offering an account of crimes in their village. For better or worse, courts were never hard to find, and there was nearly always a court with jurisdiction over any conflicts. Borough and manorial courts adjudicated local conflicts, church courts dealt with conflicts over morals as well as marriage and probate, and at the assizes the king’s justices tried serious criminal cases. In theory, at least, no one was above the law. In practice, law effectively, if imperfectly, limited the ability of those who were richer and more powerful to exploit or mistreat those below them. Subordinates were disadvantaged relative to their superiors, but they were not without recourse.5

English law limited the power of the state as much as that of individuals. “Law and liberty” were watchwords of English politics throughout the seventeenth century. Liberty meant, most immediately, that English men were free and possessed rights guaranteed by law. That law itself was participatory, quite broadly in its local enforcement and to a more limited extent in Parliament. In practical terms, English men expected to have their property exempt from taxes, and their households from pressing and quartering of soldiers, without the consent of Parliament. The central political question that emerged at midcentury was how far the king was bound by the expectations of his people, and how his behavior could be constrained. The king’s power was effectively limited by his income and the small size of his bureaucracy: he had to rely on volunteer local officials to carry out his will. Whatever the theory, in fact the king could not act without the consent of most of the governing class. Still, the tensions between theoretical royal power and practical royal dependence on the governed were the source of repeated conflict.6

The prevalence of “law and liberty” in the political discourse of the seventeenth century generated an implicit notion of freedom that became more salient as the English simultaneously complained of “slavery” to various governments and relied more heavily on slave labor in the colonies. As a legal concept, freedom was rooted in feudal tradition, when a man who was free of obligations to a feudal lord could be a full participant in society. In the late sixteenth century, freedom was connected to the liberties guaranteed by the common law and Magna Carta and represented by the idea of the “Ancient Constitution.” While the Ancient Constitution was a historical fiction, the notion of a government defined by long-established law was central to ideas of legitimacy. In England, slavery was a metaphor frequently used as the antithesis of freedom to condemn the illegitimate use of power. In the 1620s Thomas Scot had insisted that the presence of courtiers in Parliament would lead to “slavery and ruin,” while other Parliamentarians argued that the Duke of Buckingham “would make us all slaves.” Charles I insisted that he would “never command slaves but free men.” In the early years of the English Civil War, Lord Robartes saw Parliament as the only way to keep the English “free men” and urged the army to fight to protect England from becoming a land of “peasants and slaves.”7 “Slavery” in this sense referred to the use of power in particular political structures: the absolute powers of the French king, for instance, enslaved the French people; so, too, did the English Major-Generals during Cromwell’s Protectorate. Liberty was protected by the rule of law and restraints on executive power. In Barbados and Jamaica, however, slavery was a real set of social relations that denied not only freedom but also personhood to a class of people. The relationship between these two dimensions of the term “slavery” was a fundamental question that the English and their colonists faced and more often avoided.8

The English gained a perspective on their freedom through trade with other European countries, which brought them into contact with foreign peoples. When seamen and merchants traveled, they noticed differences between their country and the others. English liberty seemed to be based in England’s common law, which was more participatory than the Roman law that dominated the rest of Europe. Trade also brought foreign merchants to live in England. These merchants were only the latest migrants to England. The “English” were the product of a series of invasions of Romans, Germans, Danes, and later Normans into a British and Celtic land; through centuries of intermarriage, the differences had largely disappeared. Throughout the Middle Ages, groups of foreign merchants had settled in London and other ports. In the sixteenth century, Protestant refugees from the Continent had settled both in London and East Anglia. These new arrivals had not constituted a significant challenge to English identity: they were European and Christian. After the Reformation, English nationalism and identity came to be entwined with Protestantism and, particularly after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, national pride was attached to martial valor. The stirring patriotism of Shakespeare’s Henry V was not just a literary conceit; in 1628 Sir Dudley Digges boasted in Parliament that “in Muscovy one English mariner with a sword will beat five Muscovites that are likely to eat him.” The political upheavals of the seventeenth century did not diminish the importance of Protestantism to national identity. The inscription on the Monument, erected in memory of the Great Fire of London (1666), attributed the fire to “a horrid plot for extirpating the Protestant Religion and old English liberty, and introducing popery and slavery.”9 Trade had made the English familiar with other Europeans and sharpened their sense of national identity.

The English knew little about people outside Europe. Through much of the sixteenth century, the most important source of their limited information was The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, a mid-fourteenth century account of the peoples of the world. Mandeville’s Travels brought together a wide range of sources, some accurate and some spectacularly imaginary, and suggested that the far-flung reaches of the earth—from Africa to Asia—were peopled by fantastical societies bearing little relation to those of Europe.10 In the late sixteenth century, English travelers began to publish accounts of journeys, peoples, and places in Africa and the New World, based now on the very real voyages that were taking place at the time. Sporadic accounts of particular voyages were followed by more systematic and far-reaching reports, most notably Richard Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations of the English Nation in 1589. Hakluyt’s compilation went through two editions and revisions before his death in 1616, after which the project was carried on by Samuel Purchas. These works, along with other travel narratives, were very popular at the start of the seventeenth century.11

These newer accounts included more complex portrayals of the rest of the world, with cultures having both positive and negative characteristics and familiar and unfamiliar aspects. They still included extraordinary tales of the peoples encountered on journeys, with bizarre customs described by Mandeville attributed now to real societies as well as to mythical ones. The most far-fetched tales were credible because there were few witnesses.12 If Africa and Asia were unfamiliar, Ireland was not, especially since the Irish wars of Elizabeth’s reign. The Irish had long been seen as uncivilized, though not incapable of civilization. In some accounts, the Irish had the same characteristics of barbarism, as well as some of the same bizarre customs, as Africans: they were wild and fierce fighters, yet lazy when it came to work. Although they were Christian, their Catholicism was suspect in Protestant England. The stereotypes of the Irish that emerged in English culture are similar to stereotypes about inferiors in many places. They were applied to the Irish in Ireland and followed them when they were transported to the West Indies as servants. In this sense, the Irish were the first uncivil, racial “other” for the English.13

Traders returned from other parts of the world with material goods as well as stories. The goods, exotic and everyday, were often visible only in localized contexts: west country fishers who brought fish from the Grand Banks were unnoticed by merchants elsewhere. However, some notable voyages brought not just goods but foreign people to London, where publishers often printed accounts for wider distribution. In 1535 Richard Hawkins brought a “savage King” from Brazil to London; twenty years later, John Lok returned from Guinea with five Africans, with the aim of teaching them English so they could return to Africa to facilitate English trade there. Sir Walter Raleigh’s expedition to Roanoke in 1584 returned with two Indians, from whom Thomas Harriot developed an alphabet and lexicon of the Algonkian language. The famous arrival of Pocahontas in 1616 was thus part of a tradition of bringing people from distant lands back to England to promote trade and diplomacy.14 English traders in the late sixteenth century ranged from Muscovy and the Levant in the East, to Africa in the south, and the Spanish and Portuguese Americas to the west. The first English slaving voyage by John Hawkins took place in 1562–63, when he carried some 300 slaves from Sierra Leone to Hispaniola to sell to the Spanish. Some English people, then, had come into contact with people from all continents. The increasingly complex portrayals of the people found in other parts of the world mark a process of trying to make sense of difference. The accounts still include some fantastical elements, but other dimensions are clearly grounded in observation. The terms in which difference was defined—religion, culture, skin color, language—were fluid for a time and only became fixed through the process of building societies with ongoing relationships with those of other cultures.15

Those of us living in the twenty-first century easily think in terms of “race,” which we define in terms of skin color and hair and facial features, or as a matter of ancestry. Yet the language of race as we know it was rare in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English usage. That is not to say that skin color was not noticed, but it was not thought to define other aspects of character or personality. Even the term “race” was itself new and used most often to refer to a family or lineage, not to skin color. Insofar as race was connected to lineage, it was also deeply marked by gender. The meanings of skin color and the meanings of race were initially two separate sets of ideas. English participation in the slave trade and slaveholding later linked these ideas, but in the beginning they were distinct. And, for a time, difference was defined through other sets of terms.16

Throughout the Middle Ages, Europeans had believed that all people were descended from Adam and Eve and therefore were of one blood. The observed differences between peoples were understood as differences of religion, law, and culture, not matters of body or innate capacities. The primary distinction was between Christians and non-Christians. Distinctively racialized ideas did not appear until late in the sixteenth century, and even then they were not yet domin...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Caribbean Exchanges: Slavery and the Transformation of English Society, 1640–1700

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps and Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Trade & Settlement

- Chapter 2: Islands of Difference

- Chapter 3: A Happy & Innocent Way of Thriving

- Chapter 4: Right English Government

- Chapter 5: Due Order & Subjection

- Chapter 6: If Her Son Is Living with You She Sends Her Love

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index