![]()

1: From Freedom to Slavery

Uplift and the Decline of Black Politics

When General O. O. Howard, head of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and later, founder of Howard University, visited the Walton Springs School for freed-persons in Atlanta during the 1860s, he asked the class what message he might convey to the children of the North. The youthful Richard R. Wright is said to have exclaimed, “Tell them, General, we’re rising.” Wright’s response to Howard epitomized African Americans’ group aspirations for freedom, literacy, and political and economic independence. Wright’s distinguished career bore out his childhood prediction; he was valedictorian of the first graduating class of Atlanta University. In 1889 Wright founded the Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth, in Savannah, and served as its president. In 1921, Wright embarked on a new career as founder of the Citizens and Southern Bank and Trust Company in Philadelphia. In “Black Boy of Atlanta,” the abolitionist poet John Greenleaf Whittier helped immortalize Wright’s statement, inspiring a generation of abolitionists and reformers, black and white. Years afterward, the journalist Ray Stannard Baker observed that “We Are Rising” had become a folk motto among Georgia blacks.1

But this optimistic vision of group advancement was hard pressed to withstand a social and cultural order committed to reasserting control over the labor and lives of African Americans. In 1901, with the departure of George H. White of North Carolina, African Americans lost their last representative in Congress. His final speech praised the achievements of African Americans despite antiblack sentiment. “This, Mr. Chairman,” declared White, “is perhaps the Negro’s temporary farewell to the American Congress; but let me say, Phoenix-like, he will rise up some day. . . These parting words are in behalf of an outraged, heart-broken, bruised and bleeding, but God-fearing people, . . . [a] rising people—full of potential force.” White’s terms in Congress coincided with the decline of black political representation from the peak years in the 1870s, when sixteen blacks served in the Congress, and many more were elected to state legislatures during Reconstruction. Elected to the House of Representatives in 1896 by a coalition of Republicans and Populists, White, as the only black member of that body, could do little more than protest the assault on black life, voting rights, and status. In 1901, White introduced the first bill that sought to make lynching a federal crime. The measure was defeated. After his term, White moved to Philadelphia, where he practiced law. In 1903 he founded an all-black town, Whitesboro, New Jersey.2

White’s valedictory captured both the dismal outlook for African Americans in the post-Reconstruction era and the optimistic sense of uplift that elite blacks struggled to maintain. During a devastating period that historian Rayford Logan has called the nadir of African American history, with disfranchisement and the rout of blacks from electoral and third-party politics and the federal government’s appeasement of the forces of reaction in the South, “uplift” was a hotly contested term. For many black cultural elites, uplift described an ideology of self-help articulated mainly in racial and middle-class specific, rather than in broader, egalitarian social terms, as the epigraph that heads this chapter suggests. Black elites who spoke of uplift opposed racism by calling attention to class distinctions among African Americans as a sign of evolutionary race progress.3

This understanding of uplift, shaped by the imperatives of Jim Crow terror and New South economic development, departed from the liberation theology of the emancipation era: generally, amidst social changes wrought by industrialism, immigration, migration, and antiblack repression, post-Reconstruction advocates of uplift transformed the race’s collective historical struggles against the slave system and the planter class into a self-appointed personal duty to reform the character and manage the behavior of blacks themselves. In the antebellum period, uplift had often signified both the process of group struggle and its object, freedom. But with the advent of Jim Crow regimes, the self-help component of uplift increasingly bore the stamp of evolutionary racial theories positing the civilization of elites against the moral degradation of the masses. The shift to bourgeois evolutionism not only obscured the social inequities resulting from racial and class subordination but also marked a retreat from the earlier, unconditional claims black and white abolitionists made for emancipation, citizenship, and education based on Christian and Enlightenment ethics. It signaled the move from anti-slavery appeals for inalienable human rights to more limited claims for black citizenship that required that the race demonstrate its preparedness to exercise those rights.

Although it obtains heuristically, this transformation was never absolute. Indeed, dim echoes of Reconstruction-era social democracy persisted within the new conservatism of uplift. On the one hand, ironically, Booker T. Washington’s economic self-help ideology and his calls for property ownership were popular among many ambitious former slaves because it evoked their collective hopes for land redistribution and economic self-sufficiency. And on the other hand, the egalitarian Radical Republicanism of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, the prolific antislavery lecturer and poet, was informed by conservative civilizationist, self-help ideologies that, by the 1890s, endorsed educational and property qualifications for citizenship. But Harper, teacher of the freedpeople, temperance reformer, and novelist, expressed the postemancipation ideals of evangelical reform, speaking for those elites who directed their energies toward the social uplift of emancipated blacks. In an 1875 speech before a northern audience, she called the work of uplift a “glorious opportunity” for the youth of the race, and hoped that social advantages would not “repel” black women and men “from helping the weaker and less favored.” She concluded, “Oh, it is better to feel that the weaker and feebler our race the closer we will cling to them, than it is to isolate ourselves from them in selfish, or careless unconcern.” In this context, uplift signified the aspiring black elite’s awareness that its destiny was inseparable from that of the masses. Harper’s exhortations reflected the optimism of a postemancipation reform culture that regarded education as crucial to group advancement. Later, with black political leadership in retreat, elite blacks’ use of uplift ideology to forge a sense of personal worth and dignity in an antiblack society pointed to intraracial division along class lines virtually as an end in itself, as a sign of race progress.4

An overview of the Reconstruction era and its demise—its political and social advances for blacks, the ultimate disappointment of African Americans’ social aspirations, and the decline of black politics—is necessary for an understanding that does not merely naturalize the era’s racial ideologies and concomitant ideologies of self-help. The loss of black political power, and the economic and political repression of the Jim Crow order, including peonage, the convict lease system, lynching, and the surge in violence and racist utterances accompanying U.S. imperialism were the harsh conditions shaping black political thought. Although, as August Meier has argued, there is no essential incompatibility between ideologies of equal rights, on one hand, and self-help and racial solidarity, on the other, the conflict between these two options within a southern Jim Crow order hostile to independent black politics was by no means inconsequential. Viewed in this light, the period describes a general shift in black leadership and discourse from a sense of the complementary relation between economic and political rights to an accommodationist notion that asserted the incompatibility of political rights and “self-help.”

As George White’s farewell to Congress attested, political power and opportunities for advancement were short lived for blacks in the South. Economic competition in the impoverished South fueled smouldering racial resentments, and mob terror was constant throughout the postemancipation period. The disappointment of popular black hopes for land redistribution, the lack of labor opportunities in cities, and a series of draconian “black codes” forced many former slaves back onto the plantations as field hands in a condition of perpetual peonage. Democratic Reconstruction reforms—public education and suffrage—clashed with the dominant laissez-faire vision of economic development espoused by New South industrialists and their spokesmen. The violent repression of black politics and labor organizing, including lynching, exerted a chilling effect on black leadership. In the midst of domestic violence, the national debate on expansion found black leadership divided, protesting white supremacy in the South yet appropriating the racial rhetoric of civilization to articulate elite aspirations at the expense of earlier, unconditional claims for equal rights and citizenship.5

Reconstruction’s failed economic agenda dealt a cruel blow to the freed-people’s hopes for economic independence. The Freedmen’s Bank failed in 1874, as the life savings of many hopeful blacks was squandered in a saturnalia of overspeculation and incompetence by the bank’s white directors, including General Howard. Southern landowners, aided by the withdrawal of federal troops as part of the presidential election compromise of 1877, consolidated their control over the black labor force. Although federal troops were called in to put down labor unrest, during, for example, the railroad strike of 1877, they were seldom deployed to quell racial violence against blacks throughout the South. The inaction of the new president, Rutherford B. Hayes, created a political vacuum, as violence and fraud ensured the Republican Party’s defeat throughout the South in 1878.6

Postemancipation competition between emancipated blacks and white workers, whose social identity was predicated on racial slavery, intensified with the Panic of 1873, and persisted in the economically depressed South. Gerald Jaynes notes the development of a quota system guaranteeing whites one-half of the jobs in seaboard ports throughout the South. Indeed, the emerging racial hierarchy in the labor market paralleled that of fusion politics, which allocated political offices and patronage to whites despite black political majorities. Senator W. B. Roberts pointed to Bolivar County, in his home state of Mississippi, where black voters held a sixteen-to-one majority over whites as an example of the effectiveness of fusion politics. There, fusion allowed “the Negroes to have some of the offices, and the whites of course [to have] the best ones.” Even this state of affairs proved intolerable to whites, as Democratic “redeemers” throughout the South made good on their promise to displace blacks, particularly black Republicans, from preferred jobs.7

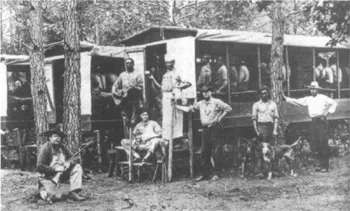

By 1890, blacks were largely excluded from industrial jobs in the South. Eighty-six percent of black workers toiled on farms or as domestic servants. As for those fledgling New South mining and mineral industries that employed blacks, their owners’ need for northern investment and cheap labor was considerable, since mining demanded of workers a costly level of skill and training. In the 1870s, black workers increasingly took their skills to the mines of the North and West, whether recruited as strikebreakers or attracted by higher wages. This led southern newspapers to complain of an “exodus” of skilled black workers. The solution to high costs and a vanishing labor supply was the convict-lease system, which depressed wages industrywide. Severe prison sentences, often for misdemeanors and other trivial offenses, yielded an abundant supply of convict workers to be leased to contractors by the state. Working conditions were wretched, with what C. Vann Woodward called an appalling death rate, but the system was profitable enough to squelch objections from virtually all quarters. In 1866, the Mississippi Central Railroad Company paid twenty dollars a month and board for each convict worker. Twenty years later, it leased convicts from the state at a cost of four dollars a month plus board. Well into the twentieth century, mining, railroad, and turpentine industries thrived on the pact between northern investors and southern economic and political elites over the use of convict labor.8

Fleeing coerced labor and intimidation, many southern blacks migrated westward in 1879, animated by the Old Testament Exodus story that had informed antislavery struggles. Their actions, as the historian Nell Painter has shown, represented a spontaneous opposition to southern tyranny independent of the moral prescriptions of black leadership. Mass politics was also an option. Although black men could exercise the suffrage, fusion with third-party movements was a bulwark against white supremacy. Such coalitions also provided blacks room for independent political agitation. In Richmond, according to Peter Rachleff, a convention of black labor leaders passed resolutions calling for racial organization and threatening white elites with migration, “provided our condition is not bettered.” Short-lived political coalitions with whites such as the Readjuster Party in Virginia helped obtain for blacks more schools and an end to exclusion from juries.9

Convict labor gang, North Carolina, ca. 1910.

Some black elites denounced the concentrated power of the planter class and condemned the New South order with the language of working-class politics. The Florida-born journalist T. Thomas Fortune and the South Carolina lawyer D. Augustus Straker (both of whom would join the out-migration of professional blacks in the post-Reconstruction period) criticized the New South and its land and railroad monopolies, the region’s widespread illiteracy, and the exploitation and intimidation of black and white labor. Fortune noted that the condition of the South’s workers had deteriorated to that of workers in Europe, where centuries of usurpation and tyranny had “reduced the proletariat class to the verge of starvation and desperation.” Voicing his skepticism that “a black skin has anything to do with the tyranny of capital,” Fortune called for an interracial labor alliance and “the more equitable distribution of the products of labor and capital.”10

Straker, writing in 1888, rejected accusations of the thriftless indolence of blacks. Although black labor had helped double cotton production since the war, “poor wages, bad laws and race prejudice” had kept “the laboring blacks and poor whites . . . in a constant state of peonage.” Straker detailed the abuses of the crop-lien system, which advanced farming supplies, tools, and subsistence necessities at exorbitant interest rates to black and white tenant farmers: “The poor laborer’s political will is yet manacled by his employer, the capitalist, and he is asked to bow or starve.” Unequal justice in the South was rooted in economic conditions “like unto the feudal times of the lord and the peasant.” Medieval conditions notwithstanding, Straker maintained that blacks had made substantial progress in property ownership. Both he and Fortune called for full citizenship rights, and their analysis of poverty and land monopoly owed a great deal to the reformer Henry George, and to the producer ethos that was central to the era’s labor ideology.11

In the rural South, African Americans were only nominally free, and third-party, working-class politics had been a viable option for many. But by the time Straker and Fortune argued for the inseparability of economic and political rights for African Americans, black leaders of the Reconstruction era were channeling labor protests against New South planters and industrialists into mainstream political parties, a pattern that would persist well into the next century, and to this day. As white vigilantes and state militias crushed black labor and populist politics, and as the gradual repeal of black voting rights throughout the South ended an already moribund tradition of radical Republicanism, the tacit cooperation of some black leaders with this state of affairs was secured by federal political appointments to “Negro jobs” and patronage. Southern intolerance of even this limited tokenism was illustrated in 1898, when Frazier B. Baker of Lake City, South Carolina, was lynched by a local mob after being appointed postmaster. Here, again, by failing to intervene, federal authorities permitted the subversion of this spoils system for blacks.12

White violence had been a constant throughout the period of Reconstruction. Lynching was increasingly employed against blacks in the late 1880s; 1889 was the first year in which more blacks were lynched than whites. Between 1893 and 1904, more than one hundred blacks on the average were lynched each year, compared to an avera...