![]()

Chapter One: Born into Salem

The week Bowditch was born, in March 1773, the front page of Salem’s Essex Gazette carried the proceedings of a town meeting in Boston—the Revolution was already brewing—but inside the paper the news was mainly from abroad. Readers learned about the “East India business” in Parliament, fires in Paris and Rome, the failure of two banking houses in Amsterdam, the opening of a 300,000-volume library in Vienna, and the sighting of a southern continent by French naval vessels in the Indian Ocean. Even the advertisements spoke of a wider world. Monsieur de Viart informed his “Friends and the Public” that he would soon be opening his dancing school for the season. Someone asked for the return of a stolen copy of Samuel Richardson’s novel Clarissa, promising “no Questions will be asked.” And among the items offered for sale were salt from Cádiz and oil from Florence, Fayal wine and Jamaican rum, Russian duck and Irish linen, and “a large Assortment of English and India GOODS.”1

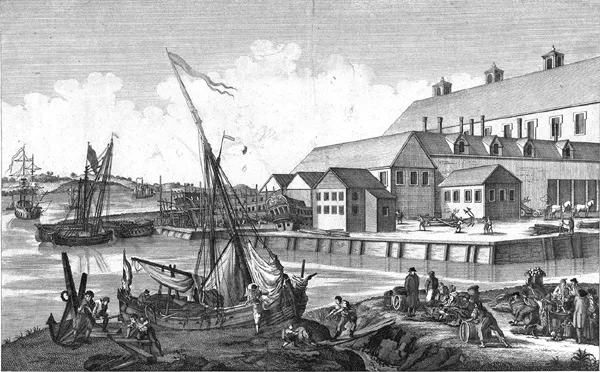

Bowditch’s seaport birthplace faced the outside world. From Salem vessels voyaged to ports along the North American coast, to the islands of the Caribbean, and even across the ocean to the British Isles, southern Europe, and the wine islands of the South Atlantic. By the eve of the Revolution it was second only to Boston as a New England port. Its 110 vessels employed about 900 men at sea, roughly three-quarters of the town’s men between the ages of fifteen and forty-five, while many on shore made a living off the seafaring economy in the town’s cooperages and ropewalks, chandleries and counting houses, wharfs and warehouses. And the wealth generated by the fisheries and deepwater commerce spun off other enterprises, from craftsmen catering to the carriage trade to teachers offering night classes in navigation.2

Like their town, the Salemites of Bowditch’s day were neither isolated nor provincial. In Bowditch’s youth his townsmen could catch a glimpse of zebra skins in a merchant’s store, pay to see a live elephant, even encounter a native of Madras on the streets.3 The wealthy and educated among them imported books, fashions, and furnishings from abroad, but cosmopolitan awareness, if not gentility, extended beyond the elite. After all, a good portion of Salem’s men had voyaged to places hundreds, even thousands, of miles away.4 Still, if Salem on the eve of the Revolution was a surprisingly global entrepôt, it was also a New England village. Its maritime population looked outward, but also inward to the community shared by 5,000 or so inhabitants, packed into 700 dwellings and shops covering about 300 acres. It was a small world. As Salemites walked the fifty streets and alleys of their town, they must have recognized almost every face. Marriage ties going back decades linked individuals in tight webs of kinship, but even those who somehow escaped the family tree were familiar, encountered in multiple contexts. Crammed together on a neck of land between the North and South Rivers, Salemites turned almost exclusively to each other to conduct most of life’s business. There were enemies and outcasts in Salem but few strangers.5

Balthasar Friedrich Leizelt, “Vuë de Salem. Salem – eine stadt in Engelländischen America,” 177–. Hand-colored etching. The harbor as it would have appeared during Bowditch’s childhood, busy with shipping and related maritime activities. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Like most of New England in the eighteenth century, the town was a relatively homogeneous place. Almost everybody was white and Protestant and had descended from English families that had settled the town over a century earlier. Whether or not their ancestors had emigrated for explicitly religious reasons, almost all were steeped in Puritan traditions, like the shunning of Christmas as a “popish” holiday and the belief in civic responsibility for the communal welfare. A small minority did not fit this profile. The provincial census of 1776 recorded 173 African Americans, enslaved and free, living in Salem, about 3 percent of the population. There were also sprinklings of French Catholic refugees from Acadia in Nova Scotia and a scattering of recent immigrants from France, Germany, and Ireland.6

As elsewhere in the colonies gentlemen and ladies stood apart from the common people. For William Pynchon, a prosperous and well-connected lawyer, the split was between what he termed “people of property” and the “rabble.” John Adams experienced that social divide firsthand. He spent an evening at Pynchon’s house “very agreeably,” drinking punch and wine and smoking pipes of tobacco in the company of other gentlemen. But outside, it was “Popes and bonfires,” wrote Adams, referring to the popular, anti-Catholic style of commemorating Guy Fawkes Day, “and a swarm of tumultuous people attending them.” There were many who fell somewhere between such genteel circles and the “tumultuous people,” of course, respectable artisans, tradesmen, and shipmasters, but all understood that this was a ranked society. Everywhere hierarchy was the reality. In households, men held the authority of masters over wives, children, apprentices, servants, and slaves. At sea, ordinary sailors deferred to the mate, who in turn deferred to the shipmaster.7

Still, to describe Salem in 1773 as a place divided by class would be misleading. More important in structuring the lives of all Salem’s residents were the lines of patronage and loyalty, personal obligation and dependency that connected people of many ranks, cutting through strata of wealth and status. In this society, individuals were defined above all by their relationships with others. Nathaniel entered this world as a member of the long-settled Bowditch family, but also as an Ingersoll, a Gardner, and a Turner, and to a lesser but real extent, as one linked to the families with whom those families had marriage ties. There were other kinds of ties that involved the granting of favor and the obligations of loyalty. What were termed “friends,” people with wealth and influence who acted as patrons to those below them, used their money and connections in what amounted to a secular act of grace.8

Nathaniel Bowditch is remembered as a citizen of the world. His New American Practical Navigator instructed men in how to range far and wide. His work as a mathematician launched him into the international Republic of Letters. But as a child, then an apprentice, and finally as a young man, Bowditch felt the influence of family and social relationships formed over decades in Salem. Events played an important role in his early life too. He was, after all, born on the eve of a revolution and a war. Even so, it was his ties to others in the community and to generations past that structured his experiences and his possibilities. They provided him with an entrée into commerce, navigation, and mathematical scholarship, the worlds of numbers.

NATHANIEL’S PARENTS, HABAKKUK Bowditch and Mary Ingersoll, were married in 1765. The groom had just returned from a four-month trading voyage to Barbados, commanding the forty-ton schooner Swan. In taking to the sea he was following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, as did his three brothers. Mary’s father had also been a shipmaster, like generations of Ingersoll men before him. Despite the similarities in background, the two families were actually following different social trajectories. Mary Ingersoll had been brought up amidst the telltale marks of a certain level of gentility—a tea table, chinaware, “Delph glass and yellow ware,” a looking glass, a clock, and “sundry pictures”—but her family never approached the level of wealth or distinction achieved by Bowditch forebears in the first half of the eighteenth century.9 Bowditch success had come with profits in trade and marriages into the highly ranked, well-connected Gardner and Turner clans. Nathaniel’s grandmother, Mary Turner Bowditch, had grown up in a mansion (later made famous as the model for Nathaniel Hawthorne’s House of the Seven Gables) that was the scene of elegant entertainments, complete with fine porcelain, silver, and glass—and three slaves to do the work. It was all part of the gentry’s new focus on the display of taste and refinement—wit and polish for men, and for women the polite “accomplishments” of music, French, and needlework. As a young girl, Mary Turner had been sent to Boston for just such a finishing.10 Had her husband, Ebenezer, maintained that level of wealth and status, their son Habakkuk might never have married the more modestly placed Mary Ingersoll. But by midcentury Ebenezer Bowditch was in serious debt, and by the time he died in 1768 he owed more than he was worth. Probate documents designated him as “gent/shopkeeper”: the “shopkeeper” a snapshot of a downhill trajectory but the “gent” an indication of the staying power of family social status in this era.11

Early in their married life Habakkuk’s seafaring career was typical of Salem’s prerevolutionary shipmasters: voyages to the West Indies in vessels laden with manufactured goods, produce, fish, lumber, and barrel staves for the islands’ plantations and their enslaved laborers, returning with sugar and molasses. For Mary the long voyages meant caring for a growing family on her own. For Habakkuk they meant facing a variety of dangers and decisions. At sea, winter winds ripped sails, broke masts, and blew vessels off course, and in summer vessels ran the risk of being becalmed. Whatever season, ships leaked, and sailors pumped. Once in the islands, the shipmaster turned merchant, with the responsibility of disposing of his freight and acquiring a return cargo on favorable terms. Before leaving Salem, captains like Bowditch met with those who had invested in the outbound cargo to discuss where the vessel should head, what prices the goods should bring, what commodities should be bought, and at what price. But it was understood that the captain must be given leeway to make decisions on the spot. Usually conditions demanded that he sail from island to island looking for the most favorable markets. Yet nobody liked to linger in the Caribbean—the possibility of succumbing to a tropical fever was too great.12

With an eye to just such risks, Habakkuk joined the Salem Marine Society in 1767. Its main purpose was to offer relief to shipmasters fallen on hard times and, even more ominously, to their widows. Membership was limited to men who actually commanded vessels. Mere owners did not face the same risks, and common seamen may have lacked the wherewithal to make the required monetary contributions into the common “box” used for assistance. Probably more critical was the esprit de corps these shipmasters shared, a common identity and pride born of years of experience, the achievement of considerable skill, and the autonomy and authority that came with command. Consider all that went into the term “shipmaster.” These were men who kept the title “Captain” for life—and beyond. The gravestone of Mary’s father, Nathaniel Ingersoll, was chiseled with the title, as Habakkuk’s would also be.13

In 1773 more immediate dangers awaited the Bowditch family: first a smallpox epidemic and then the sometimes violent fallout of anti-imperial resistance. By the time Nathaniel was two years old, all-out war had come to Massachusetts. The town did not start off as a hotbed of Patriot sentiment. Salemites must have had “an opiate administerd [sic] to them,” wrote Samuel Adams a few months before Nathaniel’s birth. In 1774, Governor-General Thomas Gage believed he was escaping the white heat of anti-British agitation when he moved the provincial capital from Boston to Salem, but by this time the town’s anti-imperial factions, led by merchants like Richard Derby, were gaining the upper hand. When Gage ordered the arrest of the Patriot Committee of Correspondence, Derby insisted that even if bail were set at “the ninetieth part of a farthing,” he would not pay. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of men pledged to rescue the committeemen, and after Gage left town somebody set fire to the store belonging to the man who had conducted the arrests. In February 1775, when Gage ordered troops into Salem to seize hidden ordnance, townspeople pulled up the drawbridge to prevent their pursuit of the weapons across the North River. Some sat atop the upraised bridge “like hens at roost,” hurling epithets at the redcoats. The cannon got away.14

Less than two months later another military mission to confiscate weapons, this one to Lexington and Concord, ended in mass casualties. Independence was well over a year away, but violence was here to stay, and with it terror. Families like the Bowditches took note. On June 17 Salemites saw a “most prodigious smoke” rising from the direction of Boston. It proved to be the terrible result of the Battle of Bunker Hill. “The destruction of Charlestown by fire (for it is all burnt down),” wrote Salem physician Edward Holyoke, has “struck our People at Salem with such a panic, that those who before thought our Town perfectly safe, now are all for removing off.” Then, in early October a British admiral ordered the HMS Canceaux “to destroy and lay waste” the coastal towns of Massachusetts, calling for “the most vigorous Efforts to burn the Towns, and destroy the Shipping in the Harbours.” Only a few days later, the HMS Nautilus fired its guns at a church spire in nearby Beverly; from across the harbor 200 hastily assembled Salemites responded with cannon. Later that same month the news of the near total destruction of Falmouth (now Portland), Maine, reached Salem. “We are yet in Salem but how soon we may be drove out I know not,” wrote Elizabeth Smith. “We are in daily expectation of a Fleet which is sent out to distroy and burn all the seaports towns [sic].”15

Once all-out war came the conditions of everyday life quickly deteriorated. Traders and fishing craft dared not venture out, and the entire maritime economy crashed. Many in the maritime workforce signed on to naval vessels and privateers and then were captured or killed. With vessels unable to venture in, and virtually no farming activity in the port towns, basic supplies ran low. “Salem people quarrel for bread at the bakers,” reported William Pynchon in the spring of 1777. By autumn, the Commonwealth was providing grain to Salem’s poor. “We crawl about and exist,” wrote Pynchon, “but cannot be said truly to live.16

Sometime during this season of fear and want, probably in the fall of 1775, when Nathaniel was two and a half years old, the Bowditch family moved three miles inland to the neighboring village of Danvers. They were hardly alone in their flight. In 1773 the town’s population numbered 6,000; by 1776 only 3,800 remained. The village lay far enough from the coast to be safe from bombardment but still offered ready access to Salem by river. The Ingersolls had roots in Danvers, and the family may still have had relations there. The Bowditches did not return to Salem until early 1779.17 Nine people occupied the small dwelling: Habakkuk and Mary, Habakkuk’s mother—a lifetime away from the Turner mansion of her youth—and six children, of which Nathaniel was the fourth. As an adult Nathaniel recalled the Bowditches as “a family of love.” A favorite memory, perhaps because it seemed to anticipate his career in astronomy, featured his mother holding him up to the window in her arms, sharing a view of the new moon. Many years later he often took his own children to see the cottage, and as they rode by he would point out the wind...