![]()

Chapter 1

Southern Rights Inviolate

William Watson had not come to America to fight. Born in a small village outside Glasgow, Scotland, he migrated to Louisiana in the 1850s. Thirty-five years old when secession fever swept over the Pelican State, he was a man of property and standing in Baton Rouge. Part owner in several businesses, with interests in coal, lumber, and steamboats, he had no direct stake in slavery. Thus he watched with concern as the convention meeting at the statehouse in January 1861 declared Louisiana an independent republic. The following month, Louisiana’s representatives joined other Southerners in Montgomery, Alabama, to establish the Confederate States of America. Six months after that, Watson found himself staring into the muzzle of a twelve-pound howitzer as his regiment charged a Union battery at Wilson’s Creek.1

Of the states that contributed troops to the battle, Louisiana was the first to take up arms. William Watson went to war not because he was a Louisianan, but because he was part of a Louisiana community that expected him to fight. The road he followed to war had many parallels, North as well as South. The war concerned the future of slavery in American society, but social forces also exerted extraordinary force on those confronting the crisis. These forces included community values, social expectations, and Victorian concepts of courage, honor, and masculinity. The actions of generals and the movements of troops are relatively easy to trace. But a battle can be fully understood only when one also considers both the motivations and the experiences of the common soldier. In the case of Wilson’s Creek, the manner in which the troops were raised and organized, their past experiences and training (or lack thereof), their image of themselves, and their understanding of what they were doing directly influenced how the battle was fought and the soldiers’ interpretation of what they accomplished by fighting it. It was the first summer of the war, and both men and values were tested.

One of the ways Watson had established himself as a bona fide member of the Baton Rouge community was by joining a company of volunteers. Replete with “tinsel and feathered hats,” the Baton Rouge Volunteer Rifle Company, formed in November 1859 in response to John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, was typical of many such organizations that existed on the eve of the Civil War.2 Supplementing the largely moribund militia guaranteed to the states under the Second Amendment of the Constitution, some volunteer companies were primarily social organizations, while others took military training seriously. However varied in character, they were the nuclei around which were formed the regiments that were to clash at Wilson’s Creek.

The creation of those regiments is an interesting story. Studies of the coming of the Civil War naturally stress the divisions within American society, but an examination of how the opposing units came into being underscores their commonalities. The goal here is not to determine which of the Northerners who fought at Wilson’s Creek were abolitionists, or how many of the Southerners who sacrificed their lives there were impelled more by states’ rights than by a desire to perpetuate slavery. The goal is to understand these men in the context of their society and analyze their experiences, particularly in relation to their home communities. This is an inexact process, heavily dependent on the sources available for study, but it reveals much about the human condition.

Fort Sumter surrendered on April 14, 1861. In Washington Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers, and from Montgomery Jefferson Davis soon made a similar appeal. But companies had been forming spontaneously throughout Louisiana since the state’s secession in January. Government officials struggled to create the bureaucracy necessary to organize, arm, and sustain military forces adequate to meet the state’s needs. They had at their disposal substantial captured Federal property, including the armaments from the U.S. arsenal at Baton Rouge. But while key points were quickly fortified, most of the nascent soldiers remained at home until the Fort Sumter crisis made war a reality. Thereafter, the pace of preparation accelerated.3

As soon as word of the bombardment at Charleston harbor reached Baton Rouge, Watson’s unit commander, Captain William F. Tunnard, called his men together to consider the crisis. They voted to create a new company, the Pelican Rifles, and offer their services to either Governor Thomas O. Moore or the Confederate government, as needed. The local press reported that the Pelican Rifles were quite willing to go to “Sumter, to the d—l, or wherever the Governor might order them to go in defense of the state or the seven-stared Confederacy.”4

Significantly, the vote was unanimous. Watson had “no sympathy with the secession movement,” although he admitted irritation at the “shuffling and deceitful policy of Lincoln’s cabinet.” Yet he could have easily dissented, as a nonslaveholder, or abstained, as a foreigner by birth and a man past prime military age. Instead he voted to go, because, as he would recall, he sought adventure and feared that staying home would harm both his personal reputation and that of his business. As Baton Rouge had a population of less than 5,500, the positions taken by its leading citizens could not escape notice.5

As a Southerner by adoption, Watson may also have been influenced by the fact that the commander of the Pelican Rifles, William F. Tunnard, was a native of New Jersey. A carriage maker, Tunnard had moved to Baton Rouge with a family that included his son, William H. Tunnard. Twenty-four-year-old Willie, as the younger Tunnard was called, had also been born in New Jersey. He was educated at Kenyon College in Ohio, yet like his father he joined the local militia and supported the Confederacy. Tunnard was a sergeant in his father’s company.6

Across the state prewar volunteer units placed advertisements in the local papers to bring their strength up to wartime levels of approximately one hundred men per company. New companies were formed as well, as plans solidified for a rendezvous of the volunteers in New Orleans. Governor Moore first issued a general appeal for men and later announced procedures for contacting the state adjutant general and enrolling for service. The public response was enthusiastic. For example, within a week of the governor’s announcement, Shreveport raised two companies, one of which was Captain David Pierson’s Winn Rifles. A third unit was also forming, marking a substantial contribution for a community of less than 2,200. Nearby Morehouse Parish, with only about 800 registered voters, put over 400 men in the field.7

Going to war was preeminently a collective experience, for it involved the entire community, not just the men who became soldiers. This can be demonstrated in Louisiana, but to an even greater extent in other states, particularly in the North, where much more historical information has survived. Throughout the 1861 campaign in Missouri, the soldiers of both sides possessed a community identity that remained as strong, if not stronger, than their allegiance to their respective regiment, state, or nation. “The soldiers of 1861,” Reid Mitchell notes, “were volunteers—independent and rational citizens freely choosing to defend American ideals. In a sense, the soldiers’ reputation would become the home folks’ reputation as well.”8

Watson’s company required relatively little preparation. Already armed and uniformed in gray, the men lacked only camp equipage, yet the citizens competed with each other to see to their possible needs. Watson recalled that elderly men and women “furnished donations in money according to their circumstances,” while “merchants and employers, whose employees and clerks would volunteer for service, made provision for their families or dependents by continuing their salaries during the time they volunteered for service.” In many cases parish-level governments appropriated substantial sums of money to support both the enlistees and their families. No one expected a long war, and such encompassing community support left men of military age with few excuses for remaining at home. Women exerted direct social pressure on men to enlist. According to a young Louisiana volunteer, “The ladies will hardly recognize a young man that won’t go and fight for his country. They say they are going to wait until the soldiers return to get husbands.”9

Soldiers maintained a sense of community identity because most of them came from the same location and enlisted at the urging of some prominent member of their hometown, native village, or county of residence. One such man was Samuel M. Hyams, who despite nearly crippling arthritis raised the Pelican Rangers. A native of Charleston, South Carolina, he was a longtime resident of Louisiana, a planter and a lawyer, serving over the years as clerk of the district court at Natchitoches, register of the land office, sheriff, and deputy U.S. marshal. After the men were mustered into service, they elected Hyams captain. This was a typical pattern.10

Community pride ran high. The Baton Rouge Daily Advocate boasted that the city’s Pelican Rifles was the first company raised outside of New Orleans to offer to serve anywhere in the Confederacy. When companies such as Tunnard’s left for the New Orleans rendezvous, the local populace always turned out in force. Hundreds, for example, gathered at the wharf in Baton Rouge on April 29 to witness the arrival of the steamer J. A. Cotton to transport the city’s volunteers downriver to the Crescent City. The mayor made a few patriotic remarks, and when the boat came into view at 11:0 A.M. cannons boomed, cheers rose, and a local band struck up martial tunes. With some confusion, amid tears and final hugs from loved ones pressing closely in, Tunnard’s men finally got on board and the lines were cast off. Similar scenes were enacted across the state.11

Not surprisingly, conditions in New Orleans were chaotic and the process of mustering-in was somewhat haphazard. Watson recalled that they had no sooner docked on April 30 when Brigadier General Elisha L. Tracy boarded the vessel and without ceremony quickly swore them into Confederate service. Another soldier, however, remembered being sworn in on May 17, by a Lieutenant Pfiiffer, and official records back up this date. Because Tracy at that time held only a state commission in the Louisiana militia, Watson probably confused two separate occurrences, as most troops were first sworn into state service and later mustered into the Confederacy’s volunteer force, officially labeled the Provisional Army of the Confederate States.12

The arriving troops were quartered at Camp Walker, a training center that had been established at the Metairie Race Course, just upriver from New Orleans. As the racing season had ended on April 9, no sacrifice of entertainment was required of the local citizenry. Although placed on the highest ground in that area, the camp was surrounded by swamp and lacked both adequate shade and fresh water. The new recruits were immediately exposed to disease, the greatest killer of the Civil War. Although some 3,000 volunteers had assembled by the first week in May, only 425 tents were available. Men crowded into nearby buildings or simply sprawled in the mud, for it rained heavily. It was quite a change, wrote one volunteer, from “the comforts and luxuries of home-life.”13

On May 11 the Pelican Rifles became part of the 1,037 men organized as the Third Louisiana Infantry. The regiment was composed of companies raised in Iberville, Morehouse, Winn, Natchitoches, Caddo, Carroll, Caldwell, and East Baton Rouge Parishes. The companies were immediately given letter designations, yet contemporary newspaper articles, wartime correspondence, and the soldiers’ postwar recollections testify to the persistence of community identification. Although proud of their regiment, the men continued to think of themselves as the Iberville Grays, the Morehouse Guards, the Shreveport Rangers, or the Caldwell Guards. These designations, under which the volunteers had originally come together, were not nicknames but their primary identification, a bond with the home community. “Be assured, Mr. Editor,” a soldier wrote the Daily Advocate, “that the Pelicans will never give Baton Rouge cause to be ashamed of her young first volunteer company.” Hometown newspapers following the Third Louisiana and the other regiments, North and South, that participated in the 1861 campaign in Missouri continued to refer to “their” companies utilizing the local designations, such as Pelican Rifles, in preference to the regimental designation. They published soldiers’ letters that reported rather graphically to the community the welfare and status of the hometown company, paying particular attention to the sick, listing them by name and describing their condition. When “Bob” wrote his hometown paper that “I must give the full meed of praise which is due our worthy Captain and his officers, for their kindnesses to their men,” he was not engaging in idle flattery, but reassuring the homefolk of their fitness for command. “Under such officers,” he continued, “the Pelicans are bound to make their mark.” By extension, so would Baton Rouge.14

If anything, the Louisiana volunteers were overly sensitive about their reputation with the folks back home after departing for New Orleans. In May, the Pelican Rifles published statements in both the Daily Advocate and the Weekly Gazette and Comet of Baton Rouge to deny a rumor that they had been mistreated by the state authorities, were demoralized, and had threatened to desert. “We are perfectly satisfied and happy,” the statement ran, “and wish no better name than that of the Pelican Rifles, which none of us will ever dishonor.” Every member of the company signed the statement.15

Strong, if friendly, rivalries existed between the companies of the Third Louisiana, and these rivalries were based in no small part on community. George Heroman bragged about the Pelican Rifles to his mother: “When we passed through the city and whenever any visitors come here they always remark that our company is the best and the cleanest looking company on the grounds.” But he was only echoing the opinion of his hometown paper. “Amid all the other companies which have formed in our State,” ran one article in the Daily Advocate, “we will venture the assertion that this company can boast of as great a proportion of sterling worth—the real ‘bone and sinew’ of the country—as any other.” Watson also believed that the Pelican Rifles were “the crack company of the regiment,” noting that they worked to maintain their superiority over the others by proficiency in drill.16

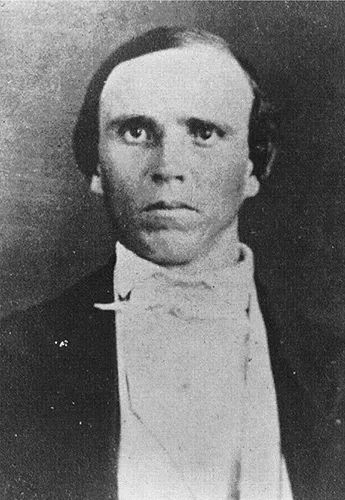

Drill was important to the regiment’s newly elected commander, Colonel Louis Hébert. Watson remembered Hébert as “something of a martinet,” a man who “took pride in his military knowledge” and was “a stickler for military form and precision in everything.” A forty-one-year-old native of Iberville Parish, Hébert had graduated from West Point in 1845 but resigned after only two years’ service to help manage his family’s sugar plantation.17 Because sugar produced through slave labor resulted in great wealth for Louisiana planters, Hébert’s reasons for backing secession might appear obvious. But who were the other men of the Third Louisiana and why did they enlist?

Unfortunately, detailed social studies exist for only a few Civil War regiments, and the Third is not one of them. We are left with the assessments made by the men themselves. Captain R. M. Hinson assured his wife that the Morehouse Guards—Company B—were “all high toned gentlemen” whom he felt honored to lead. One hesitates to question Hinson’s laudatory appraisal, as he paid for the privilege of leading these men by dying at Wilson’s Creek. But the Morehouse Guards—indeed, all the companies of the Third Louisiana—were probably a mixed lot. The best description comes from Watson, who recalled that his company contained planters and planters’ sons, farmers, merchants and sons of merchants, clerks, lawyers, engineers, carpenters, painters, compositors, bricklayers, iron molders, gas fitters, sawmillers, gunsmiths, tailors, druggists, teachers, carriage makers, and cabinetmakers. Although most of them were either natives of Louisiana or Southern-born, thirteen were from Northern states; there were also men from Canada, England, Scotland, Ireland, and Germany. Watson calculated that the number “who owned slaves, or were in any way connected with or interested in the institution of slavery was 31; while the number who had no connection or interest whatever in the institution of slavery was 55.”18

Colonel Louis Hébert, Third Louisiana Infantry (Library of Congress)

The Third Louisiana went to war under a blue silk flag bearing ...