eBook - ePub

Prompt and Utter Destruction, Third Edition

Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs against Japan

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prompt and Utter Destruction, Third Edition

Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs against Japan

About this book

In this concise account of why America used atomic bombs against Japan in 1945, J. Samuel Walker analyzes the reasons behind President Truman’s most controversial decision. Delineating what was known and not known by American leaders at the time, Walker evaluates the options available for ending the war with Japan. In this new edition, Walker incorporates a decade of new research — mostly from Japanese archives only recently made available — that provides fresh insight on the strategic considerations that led to dropping the bomb. From the debate about whether to invade or continue the conventional bombing of Japan to Tokyo’s agonizing deliberations over surrender and the effects of both low- and high-level radiation exposure, Walker continues to shed light on one of the most earthshaking moments in history.

Rising above an often polemical debate, the third edition presents an accessible synthesis of previous work and new research to help make sense of the events that ushered in the atomic age.

Rising above an often polemical debate, the third edition presents an accessible synthesis of previous work and new research to help make sense of the events that ushered in the atomic age.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1: A Categorical Choice?

Despite an expression that suggested fatigue and strain, President Harry S. Truman strode briskly into the meeting he had ordered with his most trusted advisers. It was held in July 1945 during the Potsdam Conference, at which Truman was deliberating with British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin over the end of World War II in the Pacific and the shape of the postwar world. The president told his advisers that he sought their guidance in order to make a decision about what to do with a new weapon—the atomic bomb. The first test explosion of the weapon had recently taken place in the New Mexico desert, and Truman had described it in his diary as the “most terrible thing ever discovered.”1 He wanted his advisers to consider carefully the need for using the bomb against Japan and to spell out the options available to him.

The president, dapper as always in a double-breasted suit with a carefully folded handkerchief and two-color wing tips, nodded to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson to open the discussion. Stimson had headed the War Department since Franklin D. Roosevelt had appointed him in 1940, and given that he was the cabinet member directly responsible for winning the war, his demanding duties had taken a toll. At age 78, his health was failing, but he remained as active as possible. Stimson commanded the respect of his colleagues and deputies, even if they did not always agree with him, in part because he was an embodiment of integrity and dignity. His knowledge of the atomic bomb exceeded that of any other cabinet official, and he had reflected deeply on its implications for American military and diplomatic policies.

The successful test of the bomb, Stimson pointed out at the meeting, gave the United States an important addition to its arsenal for achieving both diplomatic and military objectives. “The bomb as a merely probable weapon [was] a weak reed on which to rely,” he observed, “but the bomb as a colossal reality [is] very different.” Stimson went on to recommend that the bomb be used against Japan in order to end the war as soon as possible and avoid the huge numbers of American casualties that an invasion would incur. An assault on the Japanese islands, he told the president, “might be expected to cost over a million casualties to American forces alone.”2

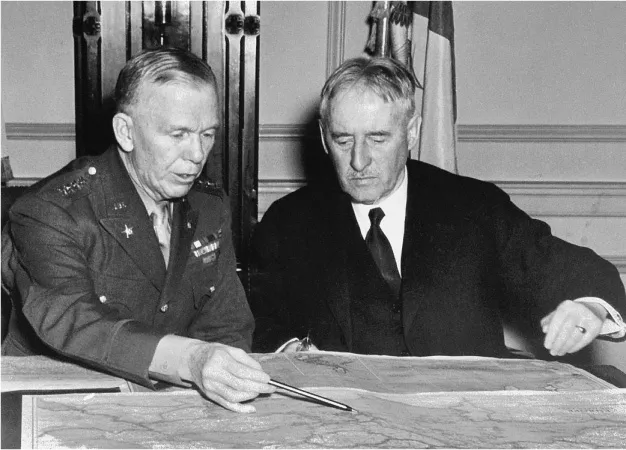

The president then called on General George C. Marshall, the U.S. Army chief of staff, the highest post that a professional soldier could attain. Marshall, reserved, taciturn, and levelheaded, personified the ideal of a career military officer. He had earned the admiration of both superiors and subordinates for his fairness, frankness, and thoughtful consideration of the options available when making policy decisions. George F. Kennan, who worked for Marshall after the general became Truman’s secretary of state in 1947, recalled “his indifference to the whims and moods of public opinion” and his discomfort with the political aspects of his job.3

FIGURE 1 General George C. Marshall and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson confer in Marshall’s office, January 1942. (The George C. Marshall Research Library, Lexington, Virginia)

Marshall agreed with the views that Stimson expressed on the question of the use of the atomic bomb. He was skeptical that attacking Japanese cities with conventional weapons would end the war, “despite what generals with cigars in their mouths had to say about bombing the Japanese into submission.” Marshall pointedly reminded the president and the others at the meeting that in a massive raid on Tokyo in March 1945, “we killed 100,000 Japanese … but it didn’t mean a thing insofar as actually beating the Japanese.” He also revealed that “Churchill estimated that we would sustain 500,000 casualties” in an invasion. Therefore, the use of atomic bombs seemed to be the best way to avoid such shocking numbers of dead, wounded, and missing Americans.4

Truman turned next to James F. Byrnes, who recently had assumed the post of secretary of state. Byrnes had served in the U.S. Senate, where he and Truman had been colleagues, and more recently as a powerful and intimate adviser to President Roosevelt. He had wielded so much authority that he had earned the title “assistant president.” When Roosevelt had decided to replace Vice President Henry A. Wallace with a new running mate at the 1944 Democratic convention, many observers, including Byrnes himself, thought Byrnes deserved the nomination. In contrast to Marshall, Byrnes thought primarily and instinctively in political terms when assessing policy issues.

Charming, bright, and capable, he was an operator, a doer, and at times a sleight-of-hand artist. Truman described him in his diary as “my able and conniving Secretary of State.” At the time of Potsdam, Byrnes enjoyed easier access to and greater influence on the president than any other adviser. Although he approached the question of using the atomic bomb from a perspective different from that of Stimson and Marshall, he reached the same conclusion. The bomb was needed, he suggested, to spare “the lives of hundreds of thousands of American soldiers.” He also argued that by shortening the war, it would save “the lives of hundreds of thousands of Japanese boys and millions more of [the] Japanese people.”5

Truman quickly made it clear that he agreed with his advisers. He declared that the two available atomic bombs should be dropped on Japanese cities because “an invasion would cost at a minimum one quarter of a million casualties, and might cost as much as a million, on the American side alone.” The president added that “a quarter of a million of the flower of our young manhood was worth a couple of Japanese cities.”6 Truman’s statement brought the meeting to a close; none of the cabinet members or military officials present expressed a dissenting view. The choice between using the bomb and facing the grim prospect of a bloody invasion of Japan seemed obvious.

The meeting described above never took place. The quotations are authentic, but the context is not. With the exception of two notations from Truman’s diary, the statements quoted were made after the war to explain why the bomb was dropped. Those statements and many others expressing the same views created a widely held myth about the decision to use atomic bombs against Japan—the belief that Truman had to choose between, on the one hand, authorizing attacks on Japanese cities with atomic bombs or, on the other hand, ordering an invasion.

Fifty years after World War II ended, an overwhelming majority of Americans who were alive at the time agreed with the decision to use atomic weapons against Japan in 1945, presumably because of the prevailing myth that the only alternative was an invasion. A 1995 Gallup survey showed that Americans between the ages of 50 and 64 approved the action by a margin of 72 percent to 24 percent; Americans aged 65 and older approved it by an even wider margin, 80 percent to 13 percent. A poll conducted 20 years later by the Pew Research Center produced similar, but somewhat more equivocal, results. It showed that 56 percent of Americans believed the use of atomic bombs was “justified,” while 34 percent thought it was “not justified.” Like the earlier Gallup poll, the Pew survey highlighted a sharp generational gap. Seventy percent of the respondents who were 65 or older supported the use of the bomb, while only 47 percent of those between the ages of 18 and 29 agreed with them.7

Despite the perception that still prevails among a majority of Americans and is especially strong among older citizens, Truman never faced a categorical choice between the bomb and an invasion that would cost hundreds of thousands of American lives. A rich abundance of historical evidence makes clear that the popular view about the use of the bomb vastly oversimplifies the situation in the summer of 1945 as the Truman administration weighed its options for ending the Pacific war. The majority opinion is unsound for the following reasons: (1) there were other options available for ending the war within a reasonably short time without the bomb and without an invasion; (2) Truman and his key advisers believed Japan was so weak that the war could end before an invasion began—that is, they did not regard an invasion as inevitable; and (3) even in the worst case, if an invasion of Japan proved to be necessary, military planners in the summer of 1945 projected the number of American lives lost at far fewer than the hundreds of thousands that Truman and his advisers claimed after the war.

If the bomb was not required to end the war within a short time, avoid a certain invasion of Japan, or save hundreds of thousands of American lives, two fundamental questions have to be addressed: (1) was the use of the bomb necessary at all, and (2) if so, what exactly did it accomplish? Historically sound conclusions can be reached only by examining conditions and decision making in the United States and Japan in the summer of 1945 and by recognizing that the considerations that led to Hiroshima were much more complex and much less clear-cut than the conventional view suggests. It is equally essential to realize that some important questions about the use of the bomb will never be answered in a definitive or unassailable way because they are matters of speculation, assumption, or uncertainty rather than matters of conclusive evidence.

Chapter 2: The Most Terrible Weapon Ever Known

One reason for the prevalence and tenacity of popular misconceptions about the use of the bomb is the mythology that has surrounded the central figure in the decision, President Truman. Truman won greater affection and esteem from the American people after his presidency, and especially after his death, than he ever achieved when he occupied the White House. In the public image of his performance as president that gradually emerged after he left office, he was honest, forthright, confident, and decisive (guided by the sign on his desk, “The Buck Stops Here”). In popular perceptions, he was, despite his limited formal education and executive experience, instinctively right in his policy judgments, using down-to-earth common sense to address complicated issues. This image of Truman, while not totally inaccurate, is deceptively incomplete. His honesty was often tempered by political considerations. His bluntness could be indiscreet or needlessly offensive. His decisiveness could lead to superficial or impulsive judgments. And his confidence was often a show that disguised insecurity and self-doubt. Historian Alonzo L. Hamby, the most perceptive analyst of Truman’s personality, has described him as loyal, considerate, thoughtful, and courageous, and at the same time petty, vindictive, thin-skinned, and suspicious. “It will not do to ask which was the real Harry Truman,” Hamby has observed. “Both were the real Harry Truman.”1 Truman had his faults as well as his admirable qualities, and it is essential to recognize both. The myths about him have not only robbed him of a portion of his humanity by placing him on a pedestal but also helped to obscure the complexity of the considerations that led to Hiroshima.

When Truman became president after Roosevelt’s death on April 12, 1945, he was very unsure of himself and his abilities. “Boys, if you ever pray, pray for me now,” he remarked to a group of reporters the day after he was sworn into office. “When they told me yesterday what had happened, I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me.”2 Truman’s doubts about himself were reflected, indeed magnified, in the views of other government officials and the American public. The president was, through no fault of his own, ill-informed and poorly prepared for the responsibilities he assumed. Roosevelt had not confided in him or attempted to explain his positions on key policy questions.

To make matters worse, Truman became president at a time when he faced a series of extraordinarily difficult problems. In April 1945 the war in Europe was ending, but the war in the Pacific still had to be won. Americans were growing weary of the war and the sacrifices it demanded. Tensions with the Soviet Union were increasing over seemingly intractable issues. The reconversion to a peacetime economy required tough decisions that could not be put off for long. Truman’s primary challenge on the economic front was to keep the United States from plunging back into depression and calming pervasive fears that the end of the war would mean the end of prosperity.

Those problems would have severely tried the abilities of any president, but Truman’s difficulties were compounded by confronting them suddenly without adequate preparation. It is little wonder, therefore, that he relied heavily on his predecessor’s advisers to provide information and guidance on what Roosevelt’s policies and intentions had been. He was committed to carrying out Roosevelt’s legacy, but he was often uncertain about what the legacy was, especially in the critical area of foreign affairs. In the early months of his presidency, Truman vacillated over whose recommendations to accept when he received conflicting advice from Roosevelt’s appointees. In those cases, he was far from being the decisive leader of legend. Rather, he was inclined to indicate his support for the position of whomever he was talking to at a given moment. Henry Wallace, who after his involuntary departure from the post of vice president had become secretary of commerce, was asked by newspaper columnist Marquis Childs in October 1945 how he was getting along with Truman. Wallace replied that their relationship “had been the most friendly; that the President had cooperated with me in everything I had wanted.” Childs commented: “Well, that is one of the great difficulties with the President; he does that way with everyone.”3 Truman’s expressions of agreement “with everyone” enabled him to avoid unpleasant confrontations and difficult choices; it also gave greater influence on policy decisions to whichever of his advisers saw him most often or at the most opportune times.

Although Truman began his presidency in the dark about many of his predecessor’s policies and commitments, one issue on which Roosevelt’s legacy seemed clear was his philosophy for fighting the war. The fundamental military strategy that Roosevelt adopted was to achieve complete victory at the lowest cost in American lives. To the extent possible, the United States would use its industrial might and technological prowess to reduce the number of casualties it would suffer on battlefronts. Roosevelt made this point to a radio audience on November 2, 1944: “In winning this war there is just one sure way to guarantee the minimum of casualties—by seeing to it that, in every action, we have overwhelming material superiority.”4 And, as his biographer James MacGregor Burns suggested, Roosevelt’s strategy was extremely successful. “Compared with Soviet, German, and even British losses,” Burns wrote, “and considering the range and intensity of the effort and skilled and fanatical resistance of the enemy, American casualties in World War II were remarkably light.”5 Truman inherited from Roosevelt the strategy of keeping American losses to a minimum, and he was committed to carrying it out for the remainder of the war.

In addition to his determination to fulfill Roosevelt’s legacy, Truman sought to curtail American casualties as much as possible because of his own combat experience. As an artillery captain during World War I, he had faced hostile fire, endured forced marches, slogged through mud, slept under bushes, and seen American soldiers killed by the enemy. He performed admirably and courageously, and he learned firsthand about the fear, fatigue, and camaraderie of combat. Truman confided to his fiancée Bess Wallace the depth of his feelings about the loss of a comrade when one of his men died while waiting to be shipped home from France. “I have been rather sorrowful the last day or so. My Battery clerk died in the hospital from appendicitis,” he wrote on January 26, 1919. “I know exactly how it would feel to lose a son…. When the letter came from the hospital informing me of his death I acted like a real baby…. I certainly hope I don’t lose another man until we are mustered out.”6 Truman therefore not only sympathized with Roosevelt’s strategy of winning the war at the lowest possible cost in American casualties on a policy level; he empathized with it on a personal level.

The development of the atomic bomb was the most dramatic example of how the Roosevelt and Truman administrations devoted their scientific, engineering, and industrial assets to a project that they hoped would help win the war at the earliest possible time. It proved to be literally an earthshaking application of the American strategy of depending on industry and technology to reduce combat losses. Although other nations sponsored modest nuclear research programs, the United States was the only belligerent that could spare the human talent and industrial resources requir...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface to the Third Edition

- Preface to the Original Edition

- Chapter 1: A Categorical Choice?

- Chapter 2: The Most Terrible Weapon Ever Known

- Chapter 3: The Prospects for Victory, June 1945

- Chapter 4: Paths to Victory

- Chapter 5: Truman and the Bomb at Potsdam

- Chapter 6: Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Chapter 7: Hiroshima in History

- Chronology: Key Events of 1945 Relating to the Pacific War

- Notes

- Essay on Sources

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Prompt and Utter Destruction, Third Edition by J. Samuel Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.