eBook - ePub

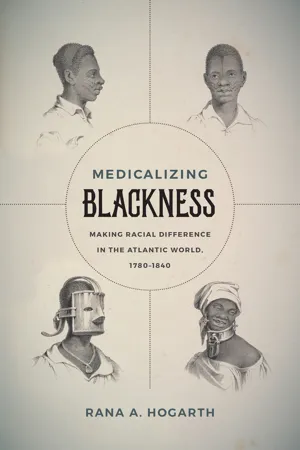

Medicalizing Blackness

Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World, 1780-1840

- 290 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In 1748, as yellow fever raged in Charleston, South Carolina, doctor John Lining remarked, “There is something very singular in the constitution of the Negroes, which renders them not liable to this fever.” Lining’s comments presaged ideas about blackness that would endure in medical discourses and beyond. In this fascinating medical history, Rana A. Hogarth examines the creation and circulation of medical ideas about blackness in the Atlantic World during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. She shows how white physicians deployed blackness as a medically significant marker of difference and used medical knowledge to improve plantation labor efficiency, safeguard colonial and civic interests, and enhance control over black bodies during the era of slavery.

Hogarth refigures Atlantic slave societies as medical frontiers of knowledge production on the topic of racial difference. Rather than looking to their counterparts in Europe who collected and dissected bodies to gain knowledge about race, white physicians in Atlantic slaveholding regions created and tested ideas about race based on the contexts in which they lived and practiced. What emerges in sharp relief is the ways in which blackness was reified in medical discourses and used to perpetuate notions of white supremacy.

Hogarth refigures Atlantic slave societies as medical frontiers of knowledge production on the topic of racial difference. Rather than looking to their counterparts in Europe who collected and dissected bodies to gain knowledge about race, white physicians in Atlantic slaveholding regions created and tested ideas about race based on the contexts in which they lived and practiced. What emerges in sharp relief is the ways in which blackness was reified in medical discourses and used to perpetuate notions of white supremacy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Medicalizing Blackness by Rana A. Hogarth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I Making Difference

Race and Yellow Fever

CHAPTER ONE

Black Immunity and Yellow Fever in the American Atlantic

It was observed the blacks were not affected with it. Happy would it have been for you, and much more so for us, if this observation had been verified by our experience.

—ABSALOM JONES AND RICHARD ALLEN, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, 1794

In the eighteenth century, death stalked the Caribbean and southeastern Atlantic coast of North America in the form of fevers that claimed vast numbers of European and African lives. Both locales garnered a reputation as unhealthy—a characterization supported by gripping accounts from visitors, residents, and extant death records. Yellow fever, also known as the black vomit, was an especially notorious killer. The first outbreak of yellow fever in the Anglophone Atlantic occurred on the Caribbean island of Barbados in 1647 and remains one of the earliest records of the disease.1 Historian J. R. McNeill credits this epidemic with taking upwards of six thousand lives, or “one in seven on the island.”2 And though the Caribbean may have led in mortality rates and epidemics due to the fever, parts of America’s mainland were equally as fever ridden and dangerous to health. Charleston, South Carolina, for example, “suffered from a disease environment that was far more malignant than that of any other British continental colony.”3 David Ramsay, the son-in-law of wealthy Charleston slave trader Henry Laurens, confirmed the region’s diseased past in his 1809 History of South Carolina. Ramsay was a physician and an amateur historian who recorded yellow fever’s seemingly relentless hold on Charleston. According to Ramsay, there were only five years in which yellow fever was not present in Charleston between 1792 and 1807. In all the other years within that period, the city languished under the disease.4

Yellow fever was no stranger to the eastern American seaboard, but it was certainly not a native disease. The yellow fever virus, carried by the bite of the female Aedes aegypti mosquito, likely arrived in the Americas from western Africa (where it was endemic) in the late seventeenth century, aided by the slave trade. Once across the Atlantic, yellow fever gained a reputation for clearing out cities, halting commerce, and attacking its victims along racial lines. A glance through extant accounts of the disease detail its ravages among sailors, ship crews, and civilians in major port towns of the American Atlantic, as well as its predilection for killing more white inhabitants than black.5 The rationale for black people’s seemingly low mortality was grounded in the assertion that as a race, black people were innately immune to yellow fever. As Philip Curtin reminds us, “Incorrect information about racial immunities to disease became one of the strongest rational supports for pseudo-scientific racism in the early nineteenth century.”6 Whether an incidental aside or a fully fleshed out point of interest, the claim of innate black immunity became a nontrivial piece of information that endured in the descriptions and accounts of the disease that physicians used to showcase their professional prowess.

More often than not, this claim appeared in accounts written by white observers, and it did little to improve the plight of African-descended peoples in the Americas, who already had the unenviable position of being classed as noncitizens or, worse, slaves based on their skin color.7 One only needs to look to the events surrounding Philadelphia’s yellow fever epidemic of 1793 to see how the pervasive racism of the era and the claim of innate black immunity worked in tandem to further oppress Philadelphia’s black population. The immune black caretakers, according to one popular-but-biased account of the epidemic, stayed behind to help the city’s whites, only to pilfer from them, price gouge, and generally take advantage of the situation. Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, two of Philadelphia’s prominent black leaders, refused to let that account go unchallenged. In 1794, they published their own account of the yellow fever epidemic, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia. Their account did more than expose the sheer wrongness of the immunity claim (Allen contracted the fever and nearly died of it); it also rebutted the accusations leveled against Philadelphia’s disenfranchised black inhabitants.

It is easy to understand Jones and Allen’s exasperation in the epigraph that introduces this chapter. The events in Philadelphia reveal a tragic but all-too-familiar story of how racial bias and medical knowledge informed and legitimized each other. In this version of the story, black caretakers buried the dead and tended to the sick during the epidemic because of the erroneous belief that black people’s bodies were constitutionally and physiologically distinct from whites. Their bodies, unlike white bodies, would be less likely to contract yellow fever and could therefore be called on and expected to serve white interests with little acknowledgment of their sacrifice. But there is another, concurrent story—the story behind the origins and circulation of the claim of innate black immunity to yellow fever. This claim had to have started somewhere. This chapter reveals how this claim not only endured over time but also became readily acceptable and widely circulated within different eras and contexts in the English speaking Atlantic. The extent of its acceptance comes through in its frequent citation by respected medical authorities, medical students, and private citizens—even after it was proven wrong.

As this chapter investigates the story behind the innate black immunity claim, it also explains why this claim endured for as long as it did. To properly flesh this out, we must first understand the circular logic that governed the ways that many whites understood racial difference in the colonial and early national period. This logic held that black and white bodies were inherently distinct because of the way each race experienced disease, and the reason why each race suffered differently from disease had to do with their different racial constitutions. Make no mistake, this logic was not advanced by a single entity or person, nor was it produced by slavery apologists; rather, it was formed out of a constellation of ideas about racial difference that prevailed at the time. It is worth noting that while these ideas maligned black bodies and rendered them ideal for laboring in the unforgiving disease climate of the Americas, they were not formulated out of a concerted effort to do so.

The claims of innate black immunity and minimal black suffering from the disease—in the rare cases black people were acknowledged to contract the disease—appeared in multiple sources. Beyond that, they spread easily enough through the repetition of medical observations about a group of people that could scarcely lay claim to their own image in the eyes of their oppressors. We need only look to a variety of eighteenth-century sources—from personal letters to published treatises—to see how, despite their differences in scope, tone, audience and context, all shared a penchant for talking about innate black immunity as something to be remarked upon because it represented a pronounced difference from white experiences with yellow fever. The net result of viewing the innate black immunity claim in this way reveals an erasure of the suffering of black victims of yellow fever and a scrutiny of blackness as a physiological peculiarity.

The first group to publicize the idea of innate black immunity was physicians whose prolonged contact with likely previously exposed black populations in Western Africa and in the West Indies earned them the right to claim eyewitness status to the phenomenon of innate black immunity. Others in mainland North America (even those outside the medical profession) eventually followed suit. Their descriptions of yellow fever make up a corpus of knowledge necessary for retracing the origins of the claim of innate black immunity to yellow fever in medical discourse. Key sources—such as Dr. John Lining’s widely circulated observation that black people were naturally resistant to the disease during South Carolina’s 1748 epidemic, Dr. Benjamin Rush’s acceptance of and then subsequent repudiation of Lining’s claims during the 1793 Philadelphia epidemic, and a handful of treatises on yellow fever from Anglo-Caribbean physicians in the late eighteenth century and American physicians in the early nineteenth century—helped reconstruct the circulation of this claim. Absent from this origin story are overt connections that link black people’s supposed innate immunity to yellow fever with their suitability as slave laborers. Slavery apologists would, of course, eventually use this claim to suggest that black people’s peculiarities were a sign of their fitness for servitude.8 However, the claim of innate black immunity to yellow fever itself was a product of medical observation that had little to do with preserving slavery. In fact, Lining made his observation at a time and in a place where slavery was not only secure but also the dominant force in southern colonial life. The tragedy of the claim of innate black immunity lies not in how it was manipulated by slavery advocates but in the fact that it needed no political manipulation to be formed in the first place.

References to innate black immunity functioned both as damaging hearsay and as medical information passed down over time and across distinct locales. When paired with sources that acknowledge black suffering from the disease, these references reveal the insidious ways the textual subjugation of black people’s bodies could work to create medical knowledge that augmented white medical authority. Even when physicians encountered black people suffering from yellow fever, they assumed that some external force had somehow interacted with those individuals’ blackness to render them vulnerable to the disease. They seldom reevaluated their assumption that blackness was a trait that influenced susceptibility. Treatises and accounts of yellow fever became the means through which white physicians circulated knowledge about racial susceptibility. More than that, they became a means for these physicians to demonstrate their professional prowess as experts on epidemic diseases. Medical knowledge in published materials allowed physicians residing in disparate regions to communicate new ideas, treatments, therapies, and knowledge to one another. At the same time, it was also a way for ideas about blackness to travel within and across different slave societies. Thus, the circulation of this claim and its subsequent citation in later medical writings show how nascent professional networks of knowledge exchange were forged through ideas about black health.

Tracing the Origins of an Idea

There is something very singular in the constitution of the Negroes, which renders them not liable to this fever.

—JOHN LINING, A Description of the American Yellow Fever, which prevailed at Charleston South Carolina in the year 1748, 1799

Yellow fever was an urban disease; the Aedes aegypti mosquito favored standing cisterns and barrels of water for breeding, not unlike those found on ships and city ports. Atlantic World urban ports like Philadelphia, Charleston, and Jamaica’s Kingston became ideal breeding grounds for the fever. Each of these cities was also home to both freed and enslaved black Africans and white settlers, which partially explains how it was that white observers began viewing yellow fever immunity through the lens of race in the first place.

To be clear, yellow fever does indeed confer immunity on its survivors, but that immunity is not heritable or racial. White settlers lucky enough to survive a bout of yellow fever would have found themselves to be immune as well. Of yellow fever’s many monikers, “stranger’s fever” perhaps demonstrates early perceptions of how immunity to the disease actually worked. Newcomers who did not have time to gain immunity to the fever were the most likely to fall ill, hence the name. Black populations that arrived in American port cities in the eighteenth century were indeed strangers to the land but not necessarily to the fever. It is likely that black populations observed to be immune to the fever may very well have acquired that immunity, particularly if they acquired it as children and then arrived in the Americas as adult “saltwater” slaves from western Africa. Of course, during the time when these physicians made their observations, how yellow fever immunity worked was not yet fully understood.

As for Creole slaves, yellow fever is mild in children, and it does not always present with classic symptoms. This means that it could have easily been mistaken for another febrile disease in childhood or ignored entirely. This helps explain physicians’ observations of adult American-born slaves escaping the disease. It also helps explain why Creole whites and those whites born in fever-prone regions largely escaped the fever.9 These circumstances perhaps excuse the physicians who insisted on innate black immunity. They do not, as historian Mariola Espinosa rightly points out, excuse contemporary iterations of this belief.10

The first-ever reference to innate black immunity to yellow fever remains difficult to pinpoint; however, early accounts of the disease indicate the disparity in the race of those who perished from it. We know, for example, that yellow fever struck Charleston in epidemic form in 1699 and left some three hundred persons dead, only one of whom was not white.11 Generally speaking, the racial specificity of victims emerged in medical accounts of yellow fever. These accounts were largely responsible for the circulation of the reference to innate black immunity, as they were most likely to capture the race, status, gender, and age of the victims. In mainland North America, one of the most widely cited accounts of the disease and the immunity claim came from John Lining, a physician born and trained in Scotland who became part of Charleston’s medical elite. Lining’s Description of the American Yellow ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Prologue

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Making Difference: Race and Yellow Fever

- Part II: In Sickness and Slavery: Black Pathologies

- Part III: Disciplining Blackness: Hospitals

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index