![]()

Chapter One: Keeping up with the Yazzies

The Authenticity of Class and Geographic Boundaries

I am talking with Kornell Johns, the lead guitarist for Dennis Yazzie and the Night Breeze Band, a well-loved group from Eastern Navajo Agency, a portion of the reservation on the New Mexico side. They’re about to play a show in Navajo Technical College’s multipurpose room for students living on campus.1 Johns is talking about the Navajo reservation battle-of-the-bands competitions he’s participated in with Night Breeze, and his perception that the judges care as much about geography as they do about music. “If we play a Battle of the Bands in New Mexico,” he says, “there’s a chance we’ll win. If we play in Arizona, the prize almost always goes to an ‘Arizona’ band. Where you’re from matters.”

Indeed, in playing at and attending numerous Native band competitions, mostly on the Arizona side of the reservation, I noticed that prizes did often go to Arizona bands. Moreover, the Arizona side of the reservation has access to more infrastructure and resources—such as Window Rock’s Naakai Hall—than the New Mexico side of the rez. These state discrepancies are also reflected in tribal politics where, until the most recent presidential election, all Navajo Nation presidents hailed from the Arizona side of the reservation and all vice presidents came from the New Mexico side (there has yet to be a president or vice president from Utah).

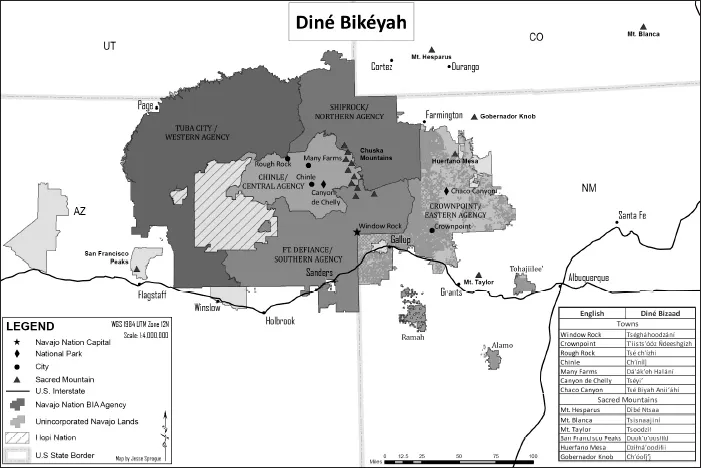

Johns’s commentary invokes discourses of east and west: state boundary lines demarcate differing perceptions of Navajo identity. While numerous dialectal differences exist for speakers from the Arizona and New Mexico portions of the reservation—for instance, gohwééh (Arizona) versus ahwééh (New Mexico) for “coffee” or yás (Arizona) versus zás (New Mexico) for “snow”—these linguistic divisions also speak to a larger sense of perceived cultural difference and the internal social hierarchies of Navajo authenticity. The Chuska Mountains, running north-south along the Arizona–New Mexico border, act as the symbolic dividing line between east and west, and between supposedly traditional and assimilated identities, with the western part of the reservation often fixed as more authentic and the locus of Navajo traditionality. While a Navajo homeland and Navajo sovereignty long preceded the demarcation of state boundaries and the birth of the United States, these constructed categories offer insight into larger debates about place, authenticity, and belonging in the Indigenous Americas and beyond. Here I highlight these themes through an analysis of origin narratives, language ideologies, the Navajo “hick” or jaan, and rural, class-based identities as they surface in the evocative songs of the country singer Candice Craig, based in Crownpoint, New Mexico.

In his provocatively titled article, “Why Does Country Music Sound White?” (2008), Geoff Mann attempts to denaturalize the supposed linkage between whiteness and country music, arguing that whiteness is not reflected in country music so much as self-consciously produced and reinstantiated by it (75). Using country music as a way to explain how race can be overdetermined through the idea of musical genre, Mann shows how country music, through its use of linguistic and instrumental twang, acts as a narrative cultural practice, something people tell themselves about themselves, where supposed racial authenticity is created through the genre’s reiterative performances. Here I argue that, given the long and deep history of Navajos performing country music in reservation spaces, it is not just whiteness but also a generation-specific, class-based Indigenous identity that is produced and affirmed through the genre of country music. Country, for many Navajos in their forties and older, indexes a twentieth-century version of Navajo tradition—it offers us a window into a contemporary Navajo politics of difference.

Recently returned from the Grand Canyon in Arizona, a college-aged family friend from Eastern Agency related her experience visiting a Navajo vendor at the canyon’s edge with a male friend, also from New Mexico’s Eastern Agency. The Navajo vendor asks where they are from. “Crownpoint,” my friend says. “That’s funny,” the vendor responds, adding, “You guys don’t look Navajo.” She proceeds to offer my friend a discount on her jewelry, and they move on to discuss other topics at hand. What does it mean to “look” Navajo, and how does “Eastern” become marked as the non-normative space, as Navajo matter out of place? We see Navajos differentiating among themselves through language about music, culture, and Navajo identity—emerging in conversations about dialect, place of origin, and social class. “Culture,” a term imported onto the Navajo reservation by early anthropologists invested in the continuity of traditional expressive practices including ceremonial music and speaking Navajo, has now taken on a similarly rigid meaning within Navajo communities and is often a fraught concept. In contrast to the broader definition given by cultural anthropologists today, culture for many Diné specifically signifies historical continuity with the past, including traditional singing, ceremonial practices, social dancing, and the use of one’s heritage language. When used in reservation spaces, the phrase “knowing one’s culture” is often synonymous with a traditional, reservation-based lifestyle and excludes so-called urban Navajos, non-Navajo speakers, and anyone who wasn’t reared in a traditional manner, however that might be conceived.

Specific places on the Navajo Nation are central to understanding the politics of culture as it relates to Navajo country-western performance. Placemaking becomes a mechanism for forging cultural intimacy and tribal sovereignty—but it also becomes a vehicle for political and social exclusion. Social class, in the way I use it here, intersects directly with a reservation-based Indigenous authenticity, or a perceived lack thereof. Possessing a working-class reservation identity, implied by such things as living on the reservation, hauling water,2 owning livestock, or having a home-site lease or grazing permit, is a coveted form of Diné cultural capital, particularly for those, such as urban Navajos, who may not possess that symbolic currency.3 By contrast, living off reservation, being more upwardly mobile, not speaking Navajo, or performing music that’s not traditionally Navajo signals a different form of class- and culture-based identity. While at least 13 percent of Navajos now live off reservation (Yurth 2012), on-reservation Navajos sometimes frame this second, more middle-class orientation as being less traditional and, by extension, less authentically Diné.

At the same time, urban and rural reservation spaces aren’t necessarily class exclusive: we also find working-class Diné living in urban areas and middle-class Diné living on the reservation. And, in fact, “keeping up with the Joneses, the Yazzies, and the Begays,”4 as one father at a recent high school graduation dinner put it, is as important to Navajo Nation citizens on the reservation as it is for those living off rez throughout the United States. This is to say that upward mobility and performances of middle-class cultural capital as a national pastime—“the white picket fence and all that,” as one of my interlocuturs put it—is as important to Diné citizens as it is to many other Americans. However, in keeping with Raymond Williams’s (1973 [1985]) theorization of the “country” and the “city” as opposite ends of a mutually constitutive spectrum, Diné citizens often reference working-class urbanites and middle-class reservation dwellers as anomalies bucking “typical” Navajo experience. In this framework, city dwellers are associated with wealth and prosperity, and reservation dwellers are associated with poverty and more primitive lifestyles. Associating poverty with Indigeneity has deep roots in federal Indian policy (Merriam 1928), and working-poor reservation identities and deprivation are thus framed as the norm, so that in local usage, terms such as “tradition,” “authenticity,” and even “Navajo” signal specific socioeconomic affiliations and understandings of Navajo culture.

With few exceptions, anthropological scholarship about Navajos has historically focused on communities living on the Arizona side of the reservation.5 This may seem unimportant, given that a Navajo homeland—Diné Bikéyah—long predates the creation of the U.S. nation or individual U.S. states. Yet because of the ideologies of authenticity attached to each state today, this omission unwittingly reifies these state-based ideologies that germinated, at least partially, off the reservation. In addition, the original reservation boundaries of the Navajo reservation, created on the return from Hwéeldi or Fort Sumner by executive order in 1868, were initially primarily in Arizona, and only later were larger portions of present-day New Mexico and Utah added to the existing Navajo reservation, also known as Naabehó Bináhásdzo.6 Due to the historical privileging of Arizona Navajo experience as representative of all authentic Navajo experience, I write this chapter from the vantage of Navajo New Mexico—the place where I lived for the first eighteen months of my fieldwork.

Anthropologists do mark Navajo New Mexican identities as Other, but Navajo New Mexicans position themselves that way, too, consistently foregrounding their difference from Arizona Navajos not just in terms of where they reside but also in their phenotype, their cultural practices, and distinct ways of speaking. From a New Mexico perspective, Arizona often stands as the unmarked portion of the reservation, the normative contingent. This politics of difference plays out particularly vibrantly on the ground in one Eastern Agency chapter7 and town8 called Crownpoint, and in the lives of community members from this marginalized reservation space.

MAP 3. Navajo Nation by Bureau of Indian Affairs Agencies (Map designed by Jesse E. Sprague)

Navajos are, and perhaps have always been, highly mobile. Since the arrival of the Spanish in 1539 and the subsequent introduction of horses and

churro sheep to the Southwest, sheepherding and range management has required Navajo people to move around.

9 In sharp contrast to more fixed Pueblo villages that are inhabited year-round, Navajos from the Dinétah phase (1550–1700) onward traditionally had at least two sheep camps (a summer camp,

keesh, and a winter camp,

keehai). Pegged as “nomadic” by early anthropologists who didn’t have the vocabulary to conceptualize a people living in two semipermanent homes, Navajos moved seasonally between their summer and winter camps. Thus, while the number of sheepherders has decreased in recent years, movement as a central tenet of Navajo identity is still highly valued. Today, for men in particular, this mobility—as for many Americans—is associated with cultural capital, where the ability to travel either for one’s job, hobby, or for pleasure is a coveted form of upward mobility. Playing in country bands allows for a similar kind of mobility, and participation in country performance increases this movement—social, economic, and geographic—for male musicians. And Navajos are still going “where the resources are at” (Don Whyte, personal interview, 23 July 2010): many Diné today work urban construction in Phoenix, Las Vegas, and elsewhere across the United States. Navajos are also known for their state-of-the-art welding, ironwork, silversmithing, and their high enlistment rate in military service, jobs that all require considerable ability to travel. Those in country bands can work the Navajo Nation rodeo circuit, itself a status marker for rural Diné men in particular. The reputation for moving around and cosmopolitan identity grounded in working-class experience led my Navajo teacher to joke: “Navajos are like beer cans … they’re everywhere!” The 2000 decennial census statistically supports this statement: 5.6 percent of Navajos live in a U.S. state other than Arizona, New Mexico, or Utah (Begay 2011, 16).

Place also figures prominently in origin stories of the Diné people, and, like Navajo identities, places are often highly contested. While some traditional creation stories tell of ancestral Diné communities emerging into this world—the fifth or “glittering world”—through a reed near Dinétah (present-day Huerfano Mesa,10 New Mexico), others trace Diné origins to a place near Canyon de Chelly (Tségi’),11 Arizona. Still other accounts, including those most commonly espoused by archeologists and other, mostly non-Native scholars,12 hold that Diné peoples migrated from Siberia across the Bering Land Bridge into present-day Alaska and then southward to the American Southwest and northern Mexico.13 From this perspective, Navajos are known as a relatively recent arrival to the Southwest.

More recently, Navajo archeologists and historians have begun to tell a different story, informed by Navajo oral histories, ceremonial knowledge, and ethnoarchaeology.14 In these accounts, southern Athabaskan speakers migrated into the Southwest in the sixteenth century but merged with other Indigenous groups already living in the region (Thompson 2009, 94) to form what later became known as the Diné people. Thus, although the first Navajo hooghan is dated to 1541 in Dinétah, this should not necessarily be understood as an indicator of Diné ethno-genesis in the Southwest. The Diné archeologist Kerry Thompson (Ashįįhí), for example, criticizes the use of linguistic evidence alone to tell the story of Diné origins (e.g., Reed et al. 2000, 65) and critiques anthropological reliance on only language as “the defining characteristic of anthropological discourse about Navajo people” (Reed et al. 2000, 240). Instead, Thompson proposes models for Navajo ethnogenesis that are more amenable to—and actively incorporate—Diné journey narratives and creation scripture as part of the evidence used to tell a place- and language-based history of Diné peoples (Thompson 2009, 241).

Language and place continue to play a central role in Diné worlds and senses of self. Indeed, dialectal preferences and language ideologies undergird the formation of Diné society, including the convergence of clans. For example, some Diné scholars now posit that Navajo, a southern Athabaskan language, was consciously adopted by “leaders of different people who shared similar lifeways but spoke different languages” (Thompson 2009, 64); Navajo became a lingua franca once a southern Athabaskan convergence in the Southwest took place. Even more specifically, Navajo journey narratives relate that Diné Bizaad was introduced by a specific clan from the west, the Tábąąhí or Water’s Edge Clan (Matthews 1897 [1994], 143; Zolbrod 1984, 301), a clan name indicating possible coastal connections with present-day California.15 Thus, even from Navajo inception as a cultural and self-governing political entity, Navajo peoples made strategic, synecdochic, and self-conscious language decisions, in which often a part—the language of one clan among many, the Tábąąhí—comes to stand in for or represent the whole, the Diné people. In each case, these origin stories matter because they have repercussions for current language ideologies, land-use practices, and legitimizing claims to sacred sites (e.g., Brugge and Missaghian 2006). As a result, these stories are often used to correlate or contradict larger narratives of place- and language-based authenticity.

If we understand Kornell Johns’s earlier comment about the role of place in battle-of-the-bands competitions—“where you’re from matters”—as a key to social citizenship more broadly, we see that social citizenship is defined differently for Navajo tribal members based on location of residence. Reservation residents on the Arizona side, for example, often leverage tribal citizenship to claim access to resources; their Eastern Agency counterparts frequently assert their rights as New Mexico and U.S. citizens rather than as tribal citizens per se. As a result, New Mexico residents often focus on a transcendent idea of Navajo culture, while Arizona residents use territorial authority, cultural knowledge, and access to a tribal elite in Window Rock to assert their Navajo identity.

Perceptions of geographic and cultural difference stem in part from the divergent histories of land allocation in the Arizona and New Mexico portions of the reservation. While parts of the reservation that lie west of the Chuskas in Arizona and the so-called Utah Strip are contiguous and bounded—that is, with the exception of the Hopi Nation and the San Juan Southern Paiute, they are not divided or partitioned by non-Navajo lands—the New Mexico portion of the reservation comprises a patchwork of multiple land owners, resulting in a checkered map (map 4), and in Eastern Agency residents often framing themselves as “matter out of place” (Dou...