![]()

Chapter One: Reading Is Power

Sometimes we don’t have any bread for a whole week, but I mean to educate my children if I have to work my hands off.

—Mississippi freedman, 1869

The overall theme of the school would be the student as a force for social change in their own state [Mississippi].

—Charles E. Cobb Jr., 1963 Prospectus for a Summer Freedom School Program

Education has always been political in Mississippi. Access to it, or rather the lack thereof, undergirded the state’s racial caste system from the antebellum era until well into the twentieth century and provided white planters with an endless supply of cheap black labor for cotton production. Both slave masters and the enslaved recognized literacy as a key to humanness, a larger world, and freedom itself. An 1823 Mississippi statute stipulated that any slaves, free black people, or mulattoes found to be assembling for the purpose of teaching slaves to read or write should receive corporal punishment “not exceeding thirty-nine lashes.” Some enslaved people learned to read secretly despite the barriers white slave owners implemented to limit black literacy.1

Black Mississippians’ enthusiasm for education intensified with the outbreak of the Civil War. Even before a Freedmen’s Bureau existed, African Americans tried to shape their own destinies by using their meager resources to set up schools. In some parts of Mississippi, the formerly enslaved acquired Bibles or primers and transformed parts of the “big house” into classrooms with semiliterate teachers.2 After the war, Freedmen’s Bureau agents reported that “colored men have paid their own money to prepare and furnish a room for a school.”3 Such initiative demonstrated the priority freed people placed on education and their desire to control their own schools.

African American state legislators during Reconstruction understood firsthand the links between education, freedom, and citizenship. The ability to read and write offered African Americans some measure of protection from exploitative labor contracts and created greater distance from their enslaved past. Southern black politicians led the charge to institutionalize universal public education. By 1870, every state in the former Confederacy had a constitution that made provision for a state-funded public school system.4 Mississippi’s 1870 school law called for tax-supported public schools with “equal advantages” for all children. The lack of a provision explicitly mandating racially separate schools differentiated Mississippi from other southern states such as Virginia. While the Magnolia State’s school law did not mandate racially separate schools, very few mixed race schools opened. Black parents focused not on the idea of their children sitting in classrooms with white students, but rather on their children’s right to an equal education.5

Black Mississippians seeking educational opportunities faced white resistance. In Chickasaw County, arson destroyed two black schools in the spring of 1871. Around the same time, in Lowndes County Klansmen intimidated black and white teachers working in black schools and vandalized such schools in Holmes County. One of the most flagrant offenses occurred in Winston County, where a group of white men visited the home of a black teacher to demand that he leave town. The teacher was not home, so the men whipped his female roommate, who died the next day from her injuries.6 Opposition also manifested itself in nonviolent forms, such as underfunding. White taxpayers begrudged having to support black education, believing that black children belonged in cotton fields rather than in classrooms.7

Black education suffered even more when the former slaveholding class regained voting rights in 1875 and overturned the Republican state government that had authorized universal public schools. Democratic political leaders prevented black men from voting and regained power through fraud, intimidation, and violence. Mississippi’s Republican governor requested federal troops to stop the lawlessness, but President Ulysses S. Grant refused to intervene. Unchecked violence and Democratic control spelled disaster for black schooling. Legislators in 1876 mandated that state and county funds could be used only for the salaries of teachers and county superintendents. They appropriated no money for the building of schoolhouses. Since emancipation, black churches had doubled as schools. Without public funding, the majority of black children continued to receive their lessons in places of worship that were poorly lit, outfitted with homemade benches, prone to winter drafts, and little conducive to academic purposes. Moreover, debates over whether white tax dollars should fund black schools at all became more common with each successive academic term. The Civil War had devastated Mississippi economically, so financing schools for white children was difficult. Providing similar accommodations for black children was out of the question.8

Reconstruction’s end in 1877 not only removed federal troops from the South but also ushered in white supremacists’ full-fledged assault on black rights, including education. In 1878, Democratic legislators reversed the 1870 statute that left the racial status of public schools up to local option and prohibited white and black children from learning in the same school. The Democratic legislature gave county superintendents the sole authority to evaluate teachers. These evaluations served as the basis for teacher salaries, allowing a superintendent to evaluate black teachers based on how much or how little the superintendent wanted to pay them rather than on their strengths and qualifications. White Mississippi public school teachers, taking cues from state lawmakers, banned their black counterparts from the Mississippi State Teachers Association.9

Gross inequity existed between white and black education. The 1890s student-to-faculty ratio in white schools in Bolivar County was 17:1 as compared to 43:1 in black schools. White teachers in the county received an average of fifty-two dollars monthly, while their black counterparts received twenty-eight dollars.10 The differentials occurred in every region of the state.

Southern Democrats codified their undemocratic rule in 1890 and thus kept black parents from unseating elected officials who denied their children quality education. Lawmakers approved a new state constitution that mandated racial segregation in education and allowed for seemingly race-neutral voting requirements that were in fact designed to circumvent the Fifteenth Amendment and disfranchise black voters. The 1890 constitution required voter applicants to be able to read a section of the state constitution or to give a reasonable interpretation of a section read to them by a registrar. Since the state did not provide voter registrars with standards to ensure uniform examinations and since 60 percent of Mississippi’s black population was illiterate, compared to 10 percent of the white population, the allegedly color-blind literacy test disqualified a large proportion of black applicants as intended. Moreover, the new constitution required citizens to pay a poll tax every year in order to vote. Other states soon followed Mississippi’s lead and “legally” disfranchised black citizens, outlining in new state constitutions voter requirements that did not technically violate the Fifteenth Amendment.11 The United States Supreme Court upheld these laws in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which sustained segregation, and Williams v. Mississippi (1898), which supported black disfranchisement.

Mississippi’s 1890 constitution limited black political participation for the next seventy-five years. Even after black literacy rates improved, the understanding clause allowed registrars to subjectively fail black applicants.12 Registrars ensured that even in black-majority counties, white voters, including illiterate ones, outnumbered black voters.13 The 67 percent of eligible black voters registered in Mississippi in 1867 decreased to 6 percent in 1892.14

White antipathy to black education had economic as well as political roots. White supremacists sought to limit black educational opportunities to maintain a large supply of cheap black labor. After the Civil War, cotton remained king in the Magnolia State, and 400,000 landless African Americans entered a “free labor” system. To restrain black Mississippians’ ability to do something other than work the land they had cultivated during slavery, the state’s political leaders limited their access to education. James K. Vardaman, a Mississippi politician who served in the state house, the governor’s mansion, and the United States Senate between 1890 and 1919, opposed funding black schools because, in his opinion, the effect of educating African Americans “is to spoil a good field hand and make an insolent cook.”15

Vardaman coupled his hostility to black education with a commitment to improving white education. As governor, he unsuccessfully proposed tax segregation: black tax dollars for black schools and white tax dollars for white schools. He took aim at the planter aristocracy in Mississippi’s black-majority counties, where state funds designated for black schools were diverted to their white counterparts. This arrangement gave white Mississippians in black-majority counties a funding advantage over white Mississippians in white-majority counties who did not have access to large amounts of black tax dollars to divert for white schools. Vardaman, a champion of poor white men and women, hoped to curb the tradition of white schools in black-majority counties being superior to white schools in white-majority counties. He believed that the status quo arrangement benefited the white ruling class.16

Remarkably, tax segregation would have benefited black education. Black Mississippians comprised 60 percent of the school population in 1899, but they received less than 20 percent of the state’s school expenditures. Black Mississippians paid city, state, and poll taxes. Their children would have fared better had black tax dollars been spent on black schools.17 This pattern of racial discrimination in Mississippi public schools where politicians redirected public school funds for black children to use for the education of white children lasted well into the twentieth century. In 1915, Mississippi spent five times more per capita on its white students than it did on its black students. By 1943, the gap had widened, and the state spent eight times as much on white education.18 Black disfranchisement ensured the continuity of funding disparities.

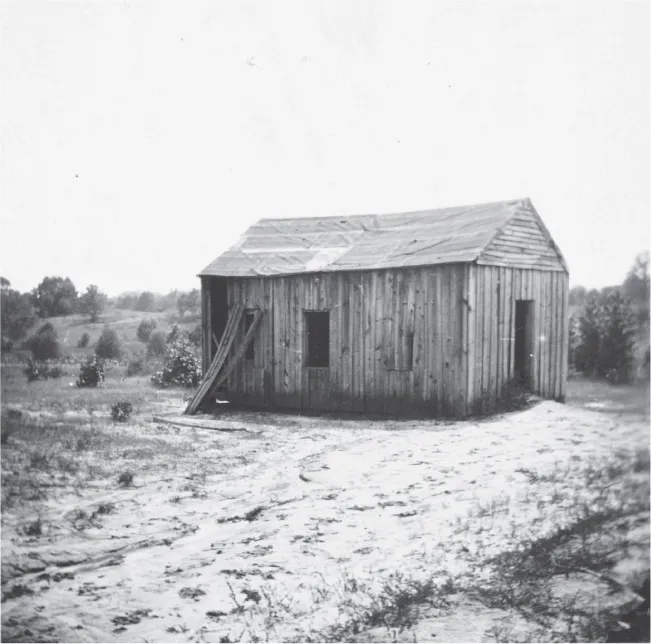

A school building for black children in Camden, Mississippi (Madison County), in 1921. The 1896 United States Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson upheld racial segregation under the doctrine of “separate but equal.” Facilities for black students were separate but never equal. (NAACP Visual Materials, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Educational disparities were most extreme in the Delta, a region that African Americans dominated in population for much of the twentieth century. Historian David Cohn once quipped that “the Mississippi Delta begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and ends on Catfish Row in Vicksburg.”19 The folksy description failed to capture the region’s racialized political economy that was underpinned by peonage, murder, and disfranchisement. The Delta contained the richest soil in the country, enabling Mississippi to produce a significant percentage of cotton for the nation. Most African Americans sharecropped on plantations owned by wealthy white planters. Sharecropping was a labor arrangement where a planter or company furnished everything but the labor. At harvest time, the sharecropper and landowner split the crop. After repaying the landowner for feed, seed, fertilizer, housing, and food, many sharecroppers remained in debt. Planters often prohibited sharecroppers from moving off the plantation until they had settled their debts.20

In addition to sharecropping, some white landowners used poor-quality black schools to foster the physical and occupational immobility of their black employees. If denied decent education, black Mississippians had very few employment prospects other than farming.21 Washington County provided an excellent example of how planters’ need for labor shaped the Delta’s public schools. Although black pupils in Washington County outnumbered their white counterparts eight-to-one in 1915, the local school district spent eight times as much per capita on white education as on black education. Thirty years later, the district spent twice as much on white education, even though three times more black children than white children enrolled in Washington County schools.22 The gross disparity remained until the 1950s when state leaders embarked on an effort to make separate education truly equal in the face of legal challenges about segregation.

Violence and terror kept most black Mississippians from challenging the status quo, but some did fight back openly. As early as 1890, black property owners in the Magnolia State dared to seek legal redress for the underfunding of black schools. The lawsuit they brought in the town of Brookhaven was especially brave given the racial climate. Between 1889 and 1945, Mississippi had 476 of the nation’s 3,786 lynchings. That number only accounted for the reported acts, and it is likely that the actual number was much higher. Even worse, not one white man was ever convicted for killing a black person in the state.23 Simply the threat of lynching was enough to maintain the color line. Author Richard Wright wrote in Black Boy, “the things that influenced my conduct as a Negro did not have to happen to me directly; I needed but to hear of them to feel their full effects in the deepest layers of my consciousness.” The Mississippi native went on to say, “indeed, the white brutality that I had not seen was a more effective control of my behavior than that which I knew.”24 The ever-present threat of bodily harm governed black actions.

Such conditions shaped the life course of Lillie Short Ayers, one of several hundred black Mississippi women who turned to CDGM’s Head Start program in 1965 to improve her living conditions and ensure that black youngsters received a quality educational foundation. Born in 1927 to sharecropper parents Jim and Lillie Short on a Delta plantation outside of Glen Allan in Washington County, Ayers learned early that the state’s system of disfranchisement and black economic dependence limited her possibilities. She attended the Strangers Home Church School on the Jordan Plantation until the eighth grade, the highest educational level available in a society where planters feared that education would upset the region’s social order. “As long as there was work in the fields,” noted Ayers, “we had to do that. We had a very short period of time that we went to school. We’d go to school after we harves...