![]()

1. A Chronicle of Lydia Thompson’s First Season in America

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

MARS–commander-in-chief, as Ma’s usually are. THE NINE MUSES, including POLLYHYMNIA. Those Thessalians who would be these aliens if they weren’t natives; dreadful Democrats, members of several secret societies who demand the right of free speaking in a state of free-dumb. Crowd of Red Republicans, unread republicans, avengers, scavengers, Greeks, sneaks, and female furies.

– Ixion

On February 8, 1868, the following classified advertisement appeared in the New York Clipper, America’s principal theatrical trade paper:

Miss Lydia Thompson, the Celebrated Burlesque, will arrive in New York in August or September. Applications for engagements to be made to Mr. Alex. Henderson, Prince of Wales’ Theatre, Liverpool.

To the theater managers, actors, and aficionados who constituted the primary readership of the Clipper, this notice was not the first they had read of Lydia Thompson and certainly not the first they had heard of burlesque. But the ad was confirmation of reports circulated over the past eighteen months that the talk of the London theater scene would be coming to the United States.

Her debut in New York had already been arranged: in the summer of 1866 George Wood, owner of several Manhattan theaters, had asked Thompson to appear at his 1,302-seat Broadway Theater near Broome Street in lower Manhattan. But before she received the invitation, Thompson had already signed to appear at the Prince of Wales Theater in London. Success there, at the Drury Lane, and especially in the winter and spring of 1868 at the Strand delayed her accepting Wood’s offer until the summer of that year. In the meantime, Wood had purchased Banvard’s Museum and Theater farther uptown on the west side of Broadway near Thirtieth Street and decided on Thompson and her company as the bill to open the refurbished theater (reportedly at a cost of $30,000) in the fall of 1868. The renovated museum would boast a theater seating over 2,200 and, beneath it, an 800-seat lecture room for the display of “living curiosities.”1 The idea of combining a “museum” of living and inanimate curiosities with a theater was not original to George Wood. P. T. Barnum, who served as adviser to Wood on the “natural history” side of his operation and who was scheduled to give the inaugural address on the facility’s opening, twenty years before had begun the practice of presenting “highly moral and instructive domestic dramas” at his American Museum.2

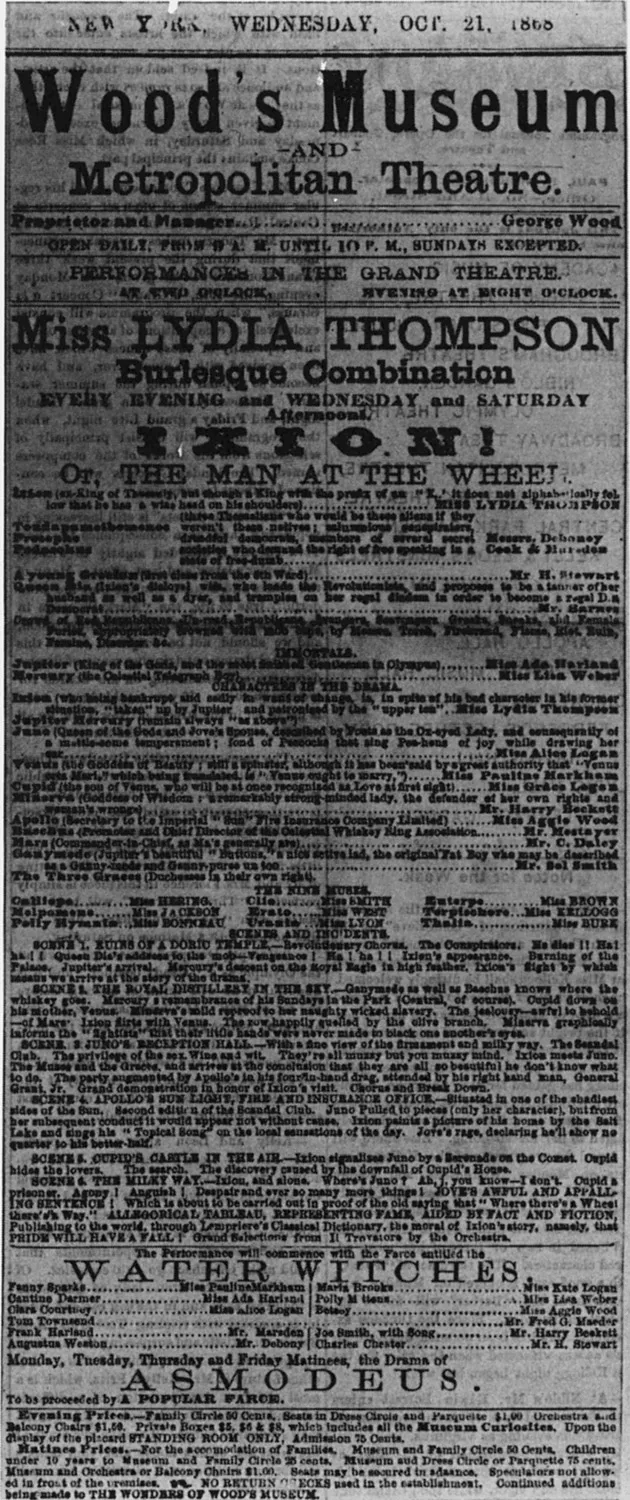

The playbill for Ixion.

(Billy Rose Theatre Collection, New York Public Library)

When she made her first of several trips to America in August 1868, Lydia Thompson was thirty-two and had been on the stage for sixteen years. Her Quaker father died when she was three, but her mother remarried a fairly well-to-do businessman, enabling Thompson to take dancing lessons from one of the most popular teachers in London. An apt pupil, Thompson was just about to leave for further training in Italy when her stepfather’s business failure necessitated her putting her dancing talents to professional use. Her first parts were in pantomimes and extravaganzas. In 1854 a Spanish dancer, billed as the most accomplished in Europe, played London. Thompson, then at the St. James Theater, proved that she could match her step for step, making Thompson something of a national cultural hero and a popular sensation.

On the basis of her success at the St. James, Thompson toured Europe and Russia for three years – the tour coming to a premature conclusion in August 1859 with the death of her mother. Over the next five years Thompson starred in a series of successful extravaganzas in London. She married a prosperous businessman and, in May 1864, gave birth to a daughter. With the death of her husband in a riding accident in June, however, Thompson once again found herself in financial straits. She accepted the offer of Alexander Henderson, manager of the Theater Royal Birkenhead (across the river from Liverpool), to star in F. C. Burnand’s burlesque, Ixion; or, The Man at the Wheel. After two seasons in Liverpool, she returned to London. Henderson went with her, and they were married in February 1868. That summer Thompson and her new husband-cum-manager left London for America on the steamship City of Antwerp, flush with her most recent success in William Brough’s Field of the Cloth of Gold at the Strand Theater. She brought with her four other performers who had already achieved considerable renown as burlesque performers on the London stage: Ada Harland, with whom she had worked at the Strand; Lisa Weber, from the Covent Garden; Pauline Markham, from the Queen’s; and Harry Beckett, the only male member of the company, a comic actor who had worked with Thompson and for her husband at Liverpool’s Prince of Wales Theater.3

By the time Thompson and her company docked in New York on August 23, the troupe’s publicist, Archie Gordon, had already begun his publicity campaign for Thompson’s debut at Wood’s Broadway Theater, now scheduled for mid-September. The campaign focused on Thompson’s European and British celebrity. Members of the New York press received an eight-page biography, which claimed that Thompson provoked such adulation among her male fans that her European tour had resulted in suicides and duels:

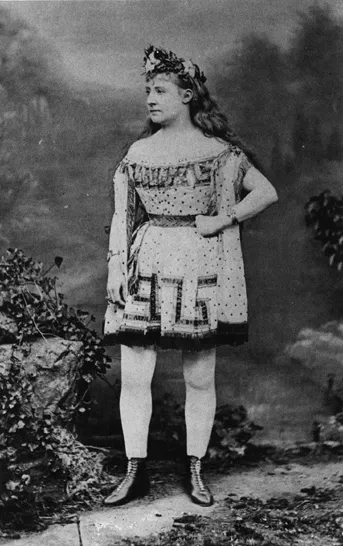

Lydia Thompson as Ixion.

(Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

At Helsingfors [Helsinki] her pathway was strewn with flowers and the streets illuminated with torches carried by her ardent admirers. At Cologne, the students insisted on sending the horses about their business and drawing the carriage that contained the object of their devotions themselves. At Riga and other Russian towns in the Baltic, it became an almost universal custom to exhibit her portrait on one side of the stove to correspond with that of the Czar on the other side. At Lemberg, a Captain Ludoc Baumbarten of the Russian dragoons, took some flowers and a glove belonging to Miss Thompson, placed them on his breast; then shot himself through the heart, leaving on his table a note stating that his love for her brought on the fatal act.4

The Season, tongue-in-cheek, warned on August 29: “She has become really quite dangerous. . . . We are [sic] an old stager, and have a heart not at all susceptible of female charms, but we are positively becoming quite afraid of Miss Lydia Thompson, and, judging from the newspaper reports of her exploits in Russia and Germany, we should imagine it will become a very grave question with the governments of these respective countries, whether her presence there again can be permitted without endangering the sanity of the whole nation.”5

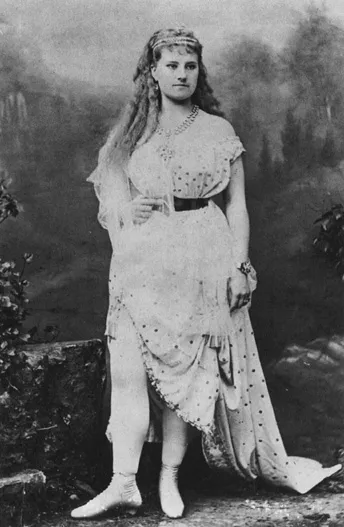

The charismatic sexuality suggested by Gordon’s publicity campaign material is curiously absent from the visual representations of Thompson and her troupe that accompanied it. The poster for Ixion, preserved by the New York Public Library, shows a demure head-and-shoulders engraving of Thompson in street clothes, which, as her biographer puts it, “resembles more a finishing school portrait than a theatrical advertisement.” Similar images of Thompson and Markham appeared in newspaper accounts, among them the New York Clipper.6 It is, of course, notoriously difficult to assess the perceived beauty of a person from a vantage point of a century later, and, as we shall see, normative notions about feminine beauty in 1868 were themselves undergoing considerable change – change that was related to the representations of femininity on the burlesque stage. However, there is little in the contemporaneous pictures or renderings of Thompson to suggest that she was a woman perceived to be of such extraordinary beauty by most that the very sight of her was enough to prompt “adoration amounting almost to mania.”7 She was petite, with dark blonde hair, a round face, blue eyes, and a somewhat long and pointed nose. Pauline Markham was the “Blonde” whom some would regard as the most attractive of the troupe. Charles Burnham, writing in 1917, remembered Markham as “the most beautifully formed woman who had ever appeared on the stage.” In its generally favorable review of Ixion, the Clipper critic called Thompson “well proportioned . . . but by no means handsome.” A few months later, the Clipper complained that the reputation of the “British Blondes” rested on their allure below the waist, not above the neck: “If you would seek for corresponding features of beauty in their faces, the disappointment is great. A more disastrous set of ballet girls, according to their facial index, it has not entered the hearts of men to conceive. In vain do we look for those touches of loveliness which make men fall down and worship the sex; scan them with a lenient eye, the result is the same.”8

Public discourse, then – both that produced on behalf of Thompson by her publicity apparatus and (perhaps influenced by it) that overlapping discourse that served as a vehicle for and a response to Archie Gordon’s efforts in the general and trade press – emphasized the famousness of Thompson, achieved through her ability to elicit the most fanatical devotion from her male following. Even papers that expressed doubts about the accuracy of Gordon’s accounts of the mass male hysteria provoked by Thompson, such as the Spirit of the Times, a New York sporting and dramatic paper, ran those accounts nevertheless. But the renderings of Thompson accompanying these accounts gave no clue as to the source of this sexual magnetism. The reader – no doubt in keeping with Gordon’s plan – would have to see for himself what all the fuss was about.

By the evening of the debut, Monday, September 28, all of the 2,265 seats in Wood’s theater were sold. Ticket prices – which the management proudly announced had not been raised for this special attraction – ranged from $1.50 for an orchestra chair to 75¢ in the family circle. To reach the theater, the audience entered on the ground floor of the building, which contained wax figures, statuary, an aquarium, and other displays, and passed by the 800-seat lecture room, where the living attractions were exhibited. Among the latter that day were a dwarf named General Grant, a giantess, and a precocious three-year-old named Sophia Gantz, billed as the “Baby Woman.” The theater critic for the Clipper penned this telling poem about the attraction with whom Thompson shared billing that evening:

Pauline Markham, “the most beautifully formed woman who had ever appeared on the stage.”

(Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

At Wood’s new museum they have

A living curiosity,

A baby woman, one they call

A natural precocity;

To tell the truth, though, we don’t think

She’s very much to talk about,

Since we can hundreds see each day

As on the street they walk about;

For slender, stout, or short or tall,

Most women babies are – that’s all.

A refreshment saloon (nonalcoholic) and shooting gallery were in the basement.9

The entertainment in the theater on the second floor began at eight p.m. with Harry Beckett in a farcical curtain raiser entitled To Oblige Benson. Then came Ixion. The play was a general lampoon of classical culture and mythological allusion composed in punning rhymed pentameter. Because no script of the version of the play presented on the New York stage survives, it is impossible to know how much of F. C. Burnand’s 1863 text survives. In Burnand’s bastardization of the Greek myth of Ixion, the king of Thessaly (Lydia Thompson) has lost all of his money betting on the horses and cannot pay the dowry for his new wife. He kills his father-in-law, which prompts his wife to lead a revolt against him. Fearing that she will succeed, Ixion calls upon Jupiter for help. The curtains open revealing Ixion crouching before the altar of Jupiter’s temple, praying for his help in escaping the wrath of his wife:

Ixion: Come Jupiter [Music – rumbling noise]

What have I done?

Pale fear!

My cheek begins to blanch.

Ada Harland, playing Jupiter, suddenly appears on the altar in a puff of smoke:

Jupiter: Who summons us by journey atmospherical?

Whose bawling has made Juno quite hysterical?

Is this the worm? [Examines Ixion through a telescope]

What means this stupid dolt?

I’ve half a mind to hurl a thunderbolt!

Ixion: Don’...