- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The field of black women’s history gained recognition as a legitimate field of study only late in the twentieth century. Collecting stories that are both deeply personal and powerfully political, Telling Histories compiles seventeen personal narratives by leading black women historians at various stages in their careers. Their essays illuminate how — first as graduate students and then as professional historians — they entered and navigated the realm of higher education, a world concerned with and dominated by whites and men. In distinct voices and from different vantage points, the personal histories revealed here also tell the story of the struggle to establish a new scholarly field.

Black women, alleged by affirmative-action supporters and opponents to be “twofers,” recount how they have confronted racism, sexism, and homophobia on college campuses. They explore how the personal and the political intersect in historical research and writing and in the academy. Organized by the years the contributors earned their Ph.D.’s, these essays follow the black women who entered the field of history during and after the civil rights and black power movements, endured the turbulent 1970s, and opened up the field of black women’s history in the 1980s. By comparing the experiences of older and younger generations, this collection makes visible the benefits and drawbacks of the institutionalization of African American and African American women’s history. Telling Histories captures the voices of these pioneers, intimately and publicly.

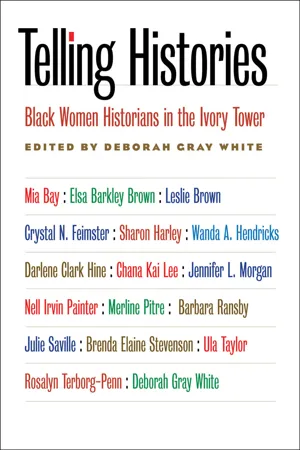

Contributors:

Elsa Barkley Brown, University of Maryland

Mia Bay, Rutgers University

Leslie Brown, Washington University in St. Louis

Crystal N. Feimster, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Sharon Harley, University of Maryland

Wanda A. Hendricks, University of South Carolina

Darlene Clark Hine, Northwestern University

Chana Kai Lee, University of Georgia

Jennifer L. Morgan, New York University

Nell Irvin Painter, Newark, New Jersey

Merline Pitre, Texas Southern University

Barbara Ransby, University of Illinois at Chicago

Julie Saville, University of Chicago

Brenda Elaine Stevenson, University of California, Los Angeles

Ula Taylor, University of California, Berkeley

Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, Morgan State University

Deborah Gray White, Rutgers University

Black women, alleged by affirmative-action supporters and opponents to be “twofers,” recount how they have confronted racism, sexism, and homophobia on college campuses. They explore how the personal and the political intersect in historical research and writing and in the academy. Organized by the years the contributors earned their Ph.D.’s, these essays follow the black women who entered the field of history during and after the civil rights and black power movements, endured the turbulent 1970s, and opened up the field of black women’s history in the 1980s. By comparing the experiences of older and younger generations, this collection makes visible the benefits and drawbacks of the institutionalization of African American and African American women’s history. Telling Histories captures the voices of these pioneers, intimately and publicly.

Contributors:

Elsa Barkley Brown, University of Maryland

Mia Bay, Rutgers University

Leslie Brown, Washington University in St. Louis

Crystal N. Feimster, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Sharon Harley, University of Maryland

Wanda A. Hendricks, University of South Carolina

Darlene Clark Hine, Northwestern University

Chana Kai Lee, University of Georgia

Jennifer L. Morgan, New York University

Nell Irvin Painter, Newark, New Jersey

Merline Pitre, Texas Southern University

Barbara Ransby, University of Illinois at Chicago

Julie Saville, University of Chicago

Brenda Elaine Stevenson, University of California, Los Angeles

Ula Taylor, University of California, Berkeley

Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, Morgan State University

Deborah Gray White, Rutgers University

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Telling Histories by Deborah Gray White in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction

A Telling History

I know of more than a score of girls who are holding positions of high responsibility, which were at first denied to them as beyond their reach. These positions so won and held were never intended for them; to seek them was considered an impertinence, and to hope for them was an absurdity. Nothing daunted these young women[.] Conscious of their own deserving [they] would not admit or act upon the presumption that they were not as good and capable as other girls who were not really superior to them.

—Fannie Barrier Williams, 1905

Some might think Fannie Barrier Williams’s 1905 commentary on “the colored girl” a peculiar place to begin this examination of late-twentieth-century African American women in the historical profession. But Williams’s words, as well as her experiences, resonate in the autobiographies compiled in this volume and in the history of black women in the historical profession. Williams was, after all, an educator and a tenacious trailblazer for professional African American women. She was, like the Chicago “girls” she refers to, audacious. One need look no further than her refusal in 1894 to withdraw her nomination for membership in the all-white, very prestigious Chicago Woman’s Club. White friends had put her name forward, and despite the fact that there were no other African American members, Williams had not expected to have to fight publicly for over a year to gain membership. She certainly did not count on being the only black member for more than thirty years. Despite her impeccable credentials, she met opposition at every turn, opposition fueled by prejudice.1 But she, like the “score of girls . . . holding positions of high responsibility,” held fast to her sense of herself as deserving and capable and did not retreat. So did the African American women historians whose stories unfold here.

They are the spiritual descendants of women like Williams. This is not hyperbole because Williams and her cohort of intelligent, educated, articulate women were revisionist historians before the history of black women was recorded. Their very bodies stood in opposition to a national script that held black women to be immoral and reproachable. Williams made this point when she rose to speak before the World’s Congress of Representative Women in Chicago in 1893. She took her very presence at the speaker’s podium as evidence that black women themselves were beginning to rewrite the conventional wisdom. Still she found it lamentable that there existed “no special literature reciting the incidents, the events, and all things interesting and instructive concerning them.”2 Clubwoman and activist Addie Hunton was likewise concerned. In a 1904 article entitled “Negro Womanhood Defended,” she spoke of an “unwritten and an almost unmentionable history” that had been generated, not by black women and “not by those who have made a systematic and careful study of the question from every point of view.” When it came to black women, Hunton called for “real study, friendly fairness, and appreciation of her progress.”3

All of the historians in this volume have answered Hunton’s call. Although not all have chosen to study and write African American women’s history, like Williams their very presence as historians is a testimony of revisionism and change—change in the national history that was previously written by men and whites, and change in the subject matter that all too often was written either without consideration of race and/or gender or for the political purpose of suppression. By querying the late entry of black women to the professional world of historians, this introduction will set the stage upon which the first of them set foot in the early 1970s. It will attempt to speak for those who did not leave the kind of record produced by those whose telling histories appear in this volume. Like the essays that follow, this introduction will put a face and a soul on women historians who might have, like the Chicago women Williams refers to, appeared on the surface to be undaunted by their assigned inferiority but who struggled mightily against the devastating effects of racism and sexism.

Anna Julia Cooper was the first black American woman to receive the Ph.D. in history in 1925, but she received it not from an American university but from the Sorbonne in Paris. Fifteen years later, Marion Thompson Wright received the Ph.D. in history from Columbia University. The lateness of their entry has been a source of inquiry because the first American woman to receive the doctorate in history, Kate Ernest Levi, did so in 1893, and the first black American man to receive the degree, W. E. B. Du Bois, did so in 1895. Besides the all-important question of why black women did not enter the historical profession in significant numbers until the post–civil rights era, there is the question of why both credentialed and noncredentialed black women students and practitioners of history eschewed black women’s history despite their intimate understanding of how their history had been misrepresented and used against them. If for no other reason than to set the record straight, it would seem that credentialed black women historians would have rushed to study and write the history of their group.4

There were many reasons why they did not. If we take our cues from those who could have been historians, prominent educated black women, we might conclude that they freely chose not to pursue academic careers in any discipline, much less history. Fannie Williams, a graduate of the State Normal School at Brockport, New York, understood that black women, even the college educated, not only had to make a living but also had to serve the race. “The ideal of scholarly leisure and the life of the student recluse is very attractive,” Williams wrote in 1904, quoting a statement she had heard at a conference entitled “Women in Modern Industrialism,” “but in the days to come, the true education will not be that which is devoted to pure academic work, but rather that which prepares for service.” Knowing too all the obstacles black women faced in the world of work, Williams quoted further: “Parents of a girl in college know, that even if they are not compelled to, their children should be able to take care of themselves.”5

That black parents knew that their daughters, in particular, had limited employment opportunities is reflected in their socialization practices. The few who could afford to give their daughters the chance to escape field or domestic work, says historian Stephanie Shaw, expected them “to make some difference in the lives of the many people in their communities who did not enjoy the advantages that they did.” They were socialized from infancy to use their education to uplift themselves and their communities at the same time.6 It should come as no surprise that Gertrude Mossell’s 1908 The Work of the Afro-American Woman, which Mossell described as “historical in character,” detailed the contributions of black women who were able to make a living doing race work. Many were teachers, but Mossell was careful to point out that Frances Watkins Harper, a writer, lecturer, and woman’s rights advocate, not only advanced the race but also “sustained herself and her family by her pen” and that Edmonia Lewis, the sculptor whose work often depicted African Americans, was able to sell her work to titled persons of Europe.7 Marion Cuthbert’s 1942 dissertation confirmed Mossell’s and Shaw’s observations. The 181 women in her sample were motivated to go to college by “their interpretation of what should be helpful in meeting the grave economic situation which confronts the Negro.” She added, “They perceive the need . . . to become self-supporting.”8

As important as the need to be self-sufficient race women was the need to project a proper image. Mossell herself wrote under her husband’s initials—as Mrs. N. F. Mossell—in part to project the image of a moral woman under the authority and protection of a man.9 Mossell did not hold up only professional women as examples of women who did important race work. She also complimented “the most humble of our women.” Quoting a southern journalist, Mossell heralded industrious black women who “hoe, rake, cook, wash, chop, patch and mend, from morning to night,” women who worked hard in the field all day and then did domestic chores at night, women who in addition to everything else raised chickens and turkeys, geese and ducks. In other words, for Mossell, it was important for educated women to do race work, but it was even more important for all black women to uphold an image of industriousness. This too constituted uplift race work.10

This is important to this discussion of black women in the historical profession because it is easy to conclude, and in fact it has been argued, that black women did not pursue careers in history because history did not lend itself as easily as other professions to racial uplift. It has also been argued that when black women did write history, they did so as part of the project of racial uplift and thus avoided the particular history of African American women.11 These arguments may help us understand why black women arrived late to the historical profession, but there is more that we need to look at, something suggested by Mossell.

An education enabled black women to practice a profession that provided sustenance to both the individual and the race, but any woman could help uplift the race by projecting an unimpeachable image. Image, therefore, was a central concern for black women because conventional historical wisdom defined them as promiscuous and explained them to the nation as ignorant and uneducable. To say that black women were disadvantaged by this history is to understate the obvious. More important for the project at hand is that these historical interpretations so circumscribed the black woman’s existence that it was impossible for even the college educated to escape the consequent discrimination that prevented her entry into the professional ranks of those who wrote history. In other words, it was nearly impossible for black women to become historians because they were caught in the hopeless dialectic that went something like this: in order to enter the historical profession, black women had to escape a race and gendered history that perpetuated discrimination, but the only way to escape that history was to become historians.

This dilemma was not lost on some could-be historians. They felt the burden of discrimination, and in what amounted to some rather classist statements, they unhesitatingly complained. Said clubwoman Sylvanie Francoz Williams of Louisiana, “For the educated Negro woman has been reserved the hardest blow, the darkest shadow and the deepest wound.”12 In a similar vein, Addie Hunton, the first black graduate of Philadelphia’s Spencerian College of Commerce in 1889, regretted that “those who write most about the moral degradation of the Negro woman know little or nothing of the best element of our women.”13

These women understood how history functioned not only to oppress them but also to keep them from becoming historians, professional or otherwise. Their particular history, the black woman’s history, was especially oppressive.14 Hunton alluded to its prohibitive nature when she delicately noted the “almost unmentionable history of the burdens of those soul-trying times when, to bring profit to the slave trade and to satisfy the base desires of the stronger hand, the Negro woman was the subject of compulsory immorality.”15 Sylvanie Francoz Williams was more direct. So painful was the wound of the black woman’s history, she argued, that “her detractors rely upon her not voluntarily reopening it, even to probe it for its cure.” Perceptively, Williams maintained that the black woman’s “sensitiveness on this point has been the greatest shield to the originators of the scandal.” Using the slanderous remark of a reporter who wrote, “I cannot conceive of such a creation as a virtuous black woman,”16 Williams demonstrated how historical reality could be as much of a hindrance as mythology and why so many chose to leave both alone:

On reading such an expression, the first impulse is a burst of righteous indignation, but it is soon followed by a wave of pity for one who has “lived all her life” amid such environments, [who] at last, driven to desperation, violently tears aside the curtain to expose the skeleton existing in her own private closet.17

Williams’s statement becomes all the more salient in light of Shaw’s observation that black women of the middle and striving classes were socialized from infancy to avoid any hint of immodesty. According to Shaw, parents understood the economic and sexual exploitation that black women were subject to, and they also understood that if their daughters were to make the most of the opportunities available to them, “they would have to be extremely circumspect and never give the slightest hint of impropriety, otherwise they might be negatively typecast.” Childrearing practices, therefore, especially those involving girls, were aimed at instilling “Victorian ideals of restraint regarding matters of female sexuality.” Knowing that their daughters did not have to “do anything to ‘attract’ the kind of attention that resulted in sexual abuse,” parents “expected their daughters to project a flawlessly upright appearance.”18 To talk about or study the black woman’s “enforced immorality,” even to expose the wanton power of white men, the evil of systemic raced sexism, the admirable qualities of black men and women, exposed the could-be historian to the boomerang effect outlined so well by Williams. Could-be black women historians were too smart not to know the figurative molesting potential of the “unmentionable history” Hunton alluded to. Surely it was easier and less dangerous to rewrite history through work that uplifted, and thus altered, the community that whites analyzed with disgust than to risk being slandered for revising the historical canon.19 Just as historian Darlene Clark Hine argues that twentieth-century black women developed a culture of dissemblance and a supermoral persona as a defense against rape, I suggest that this same conscious and unconscious mindset was one of several factors keeping educated black women away from writing anything but celebratory history and away fro...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Telling Histories

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Un Essai D’ego-Histoire

- Becoming a Black Woman’s Historian

- A Journey Through History

- Being and Thinking Outside of The Box

- My History in History

- The Politics of Memory and Place

- History Without Illusion

- On The Margins

- History Lessons

- The Death of Dry Tears

- Looking Backward in Order to go Forward

- Journey Toward a Different Self

- Bodies of History

- Experiencing Black Feminism

- Dancing on The Edges of History, But Never Dancing Alone

- How a Hundred Years of History Tracked Me Down

- Not So Ivory

- Contributors