![]()

1 Adapting to Segregation

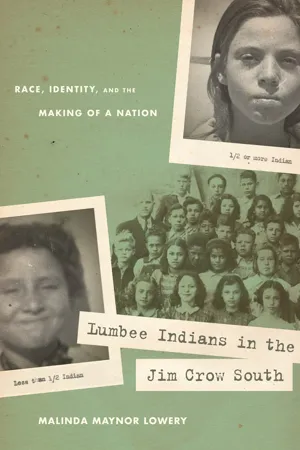

My family photographs ring with layers of belonging; we have one of the Pembroke “graded school,” or elementary school, that features my dad’s sister Faye (Figure 2). She is on the left end of the front row, and my great-uncle Theodore Maynor is the teacher (third row, left end). Aunt Faye was in the first grade, but some of those children on the top row don’t look like first graders—they’re preteens but most likely in their first year in school. Each child in this picture came from an Indian household; they had two Indian parents and lived within a few miles of Pembroke, close enough that they could walk to school. Few Indian children had access to a school bus, but the Pembroke graded school did have a sturdy brick building, evincing their modest prosperity compared to more isolated communities. I can imagine my grandmother Lucy mending the special collar she had sewn for Faye’s dress the morning this picture was taken; I can picture Faye practicing an appropriately serious expression in front of her mother’s dresser mirror—the only mirror in their five-room house, which was large for that time and place. My grandfather Wayne, a schoolteacher like his brother Theodore, was probably in the yard feeding the hogs; or maybe he was plating a few biscuits with molasses for my dad, Waltz, then only five years old. In a few years, Waltz, Faye, and their siblings would rise before dawn to pick cotton so they could go to school that day.

But this scene is just a fiction to me; my grandmother died before I was born and my grandfather died when I was three, so I don’t recall their voices or personalities or the atmosphere in their home. In fact, just trying to access 1938 is difficult. I didn’t go to a segregated school, but the faces in my class pictures looked just as varied as these do. This photo poses some questions: How did the segregation era, marked by a supposedly iron-sided wall between the races, evidence so much variety? What were the contours and boundaries of racial segregation for Native American southerners? How did their identities function, and how did the concept of race become institutionalized out of an identity based on kinship and settlement?

FIGURE 2. First-grade class at Pembroke Indian Graded School, circa 1937 (Dorothy Blue and the Lumbee River Fund Collection, Livermore Library, University of North Carolina at Pembroke)

These are questions that historians now ask, knowing that race and color became definitive categories in American society in the twentieth century. But at that time, Indians asked another question, one that had little to do with their position in the racial hierarchy and everything to do with their identity as a People: how do we maintain our autonomy while promoting opportunity and prosperity among our people? Faced with the challenge of an emerging color line and whites’ defense of it, the answer was no less ambiguous than the social and political air they breathed.

By 1910 white supremacy dictated the separation of racial groups in urban public facilities—schools, churches, restrooms, drinking fountains, movie theaters, buses, streetcars, hospitals, and other places. In Robeson County, that separation was threefold in the county seat of Lumberton. There were different facilities for whites, blacks, and Indians. In the county courthouse, each group had its water fountains and restrooms, while the Lumberton movie theater boasted a balcony divided by wooden partitions for the Indian and black patrons. In the county’s private places and in rural areas and small towns, however, the picture is less divided and more like the one of my aunt’s school class: variegated, but with a certain logic once one looks below the surface. White supremacy was at once arbitrary and systematic.

Indians took step-by-step advantage of the post-Civil War racial environment to add another layer to their strategies for maintaining identity. Segregated schools and churches, along with the growing obsession with a hierarchy of color and ancestry, fostered a racial identity and helped Indians affirm their identity as fundamentally different from whites and blacks. However, adopting segregation to preserve distinctiveness proved to be a double-edged sword: excluding blacks and whites from their community assured Indians control over some of their own affairs, but it also conceded whites’ power to govern race relations. Indians operated within the constraints of white attitudes about the racial hierarchy and, to a certain extent, had to determine their social boundaries according to what whites were willing to accept. Even so, they employed their own values in monitoring social contact with both whites and blacks.

The state evidently approved of their expressions of Indian identity, and in 1885 the legislature recognized Robeson County Indians as a “tribe” Unlike racial minorities in the late nineteenth century, Indian tribes were acknowledged entities that had independent political structures and historic claims. Under U.S. law, Indian tribes primarily had political identities, not racial ones. “Tribe” and “race” were not synonyms; rather, both words reconstructed a People and imposed rules on its opportunities, prosperity, and social mobility in different ways. However, when legislators recognized Robeson County Indians as a separate group in 1885, ideas about the racial hierarchy and a political identity converged for whites. Increasingly, Indians would struggle to use both to their strategic advantage. Being a legally recognized “tribe” created new opportunities for organizing to preserve autonomy, while being a socially acknowledged “race” authorized white power and control.

The 1885 law established Indians’ right to separate schools and complicated their political identity through the exercise of that right. Indians also retained the ballot—in contrast to their black neighbors, whom Conservative Democrats disfranchised in 1900. With a tribal identity and the right to vote, Indians could use separate schools and churches to gain political influence. Indian leaders debated the best way to handle whites’ power over their schools and churches. Should whites or Indians pastor Indian churches? Should Indian children with darker skin and curly hair be admitted to Indian schools? Indian-only social institutions then precipitated conflict within a community already characterized by a decentralized political and social structure. As this conflict became entrenched, Indians began to look beyond kin and settlement identification to institutionalize race and assert their tribal identity. The coexistence of “race” and “tribe” as identities fostered a degree of internal community disagreement as social and political ties between Indians and whites expanded and as ties between Indians and blacks diminished.

THE LOWRY WAR, characterized by a multiracial alliance, had a profound impact on the Republican and Democratic battle for power during Reconstruction. Historian William McKee Evans demonstrates that the Lowry gang’s aggressive and violent resistance to oppression divided Republican Party supporters between those who supported fighting violence with violence and those who believed that deferring to whites was the most productive political route. These divisions stalled Republican momentum significantly enough to allow Democrats to achieve consistent, though not complete, victories in North Carolina elections throughout the 1870s and 1880s.1 The multiracial coalition that Henry Berry Lowry assembled lost its political effectiveness amidst Republican divisions and a culture of deference that reinforced paternalistic white power.

If the Lowry War left a lasting political legacy, it was that Democrats could not take their victories for granted; Indians, blacks, and some whites still allied at the ballot box in favor of Republicans. Democrats thus began to court Indian voters as Robeson County became critical to the party’s recapture of control in North Carolina. Democrats observed the county’s tiebreaking participation in the election for delegates to the state 1875 Constitutional Convention, and they saw a unique opportunity to use the racial divisions in the county to their advantage. This convention was called to amend the Republican 1868 state constitution, which gave nonwhites the right to vote. To Democrats, the 1868 constitution represented “carpetbagger” and “Negro” rule, and when they regained control of the state legislature in 1870, they were eager to rewrite it. The two convention delegates from Robeson County gave the Democrats a one-vote majority at the convention. One Robeson attorney who later wrote about these events recalled that those two Democratic delegates only won Robeson by “the slimmest of majorities” and implied that the county’s party leaders rigged the election to provide the convention with two Democrats. Though officials denied such chicanery, Democrats achieved victory by throwing out the votes from four county districts because the poll books did not include the vote count as the law required. At least one of these districts, Burnt Swamp, had a majority of nonwhite voters. Voters from the discarded districts protested at the county courthouse as the votes were being counted, but election officials gave the victory to the Democratic candidates.2

TABLE 1. Robeson County Population, 1860, 1870, and 1900 |

| | 1860 | 1870 | 1900 |

| White | 8,572 (55.34%)* | 8,892 (54.67%) | 19,556 (48.46%) |

| Free persons of color/colored | 1,462 (9.43%)* | 7,370 (45.33%)* | 3,877 (9.62%)* |

| Negro | N/A | N/A | 16,917 (41.92%) |

| Slaves | 5,455 (35.21%) | N/A | N/A |

| TOTAL | 15,489 (100%) | 16,262 (100%) | 40,350 (100%) |

* Includes Indians

Notes: The kinds of data collected by census enumerators varies from census to census. It is impossible to directly compare the numbers of voting-age males across racial groups across decades; only the 1900 census contains data specific enough to allow comparisons of voting-age males. These general population numbers thus only give the reader an indication of how the county was divided.

Sources: University of Virginia Geospatial and Statistical Data Center, United States Historical Census Data Browser (University of Virginia, 1998), available online at http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/census/ (18 August 2004 and 7 December 2006); Ernest D. Hancock, “A Sociological Study of the Tri-Racial Community of Robeson County, North Carolina” (master’s thesis, University of North Carolina, 1935), 36.

Demographic changes in Robeson County before and after the Civil War demonstrate the relationship between voter populations and the Democratic and Republican contest. Emancipation had tremendous political significance in Robeson County. In 1860 whites dominated the electoral process because Indians and slaves were not allowed to vote. But in 1870 whites held a slim majority in the population as a whole. Republicans could change the balance of power if they could convince a few whites to join Indian and black voters. The 1900 census for Robeson County reveals that there were more Indians and blacks in the county than whites (Table 1). This reality indicates why Democrats believed they had to use a campaign of terror to win support at the polls.

Had Indians and blacks continued to vote together as they had during and immediately after Reconstruction, white Democrats would have lost every election if just a few poor whites joined Indian and black Republicans, which was the voting trend in many parts of the state through the 1890s. Historian Kent Redding argues that Republicans successfully employed racial identity politics long before the Democrats engaged their white-supremacy campaign. Although Conservative Democrats gained a majority in the state legislature as early as 1870, local races remained hotly contested and black Republicans continued to hold offices in many eastern counties. In Robeson County, for example, Republicans comprised the majority of registered voters, but the Lowry War divided them sufficiently to prevent them from gaining permanent control. One Democratic politician remembered that Indians were “chiefly Republican” through the 1890s.3 The ruling status of Democrats was hardly secure, but the presence of the Indian population gave Robeson Democrats an opportunity to secure a clear majority. If they convinced Indians to join their cause and distance themselves from black voters and the Republican Party, Robeson Democrats could potentially eliminate any meaningful Republican opposition.4

Indians probably saw that this arrangement could work to their own advantage as well. In the aftermath of the Lowry War, some Indians likely recognized that their own political voices might be silenced, and they therefore sought to maintain what power they had. With an immovable place in this emerging race-based political system—guaranteed by their white Democrat friends—Indians could maintain some control over their own affairs while not threatening whites. Establishing Indian-only schools and churches secured this autonomy and also served another purpose: maintaining kinship networks. Schools and churches drew extended families closer together. Prior to the Civil War and during Reconstruction, Indians had learned and worshiped more informally, without attachments to outside sources of funding or church denominations. At least a few Indians attended school with blacks in the county seat of Lumberton during Reconstruction; a white Presbyterian minister and prominent Republican activist ran the school.5

When North Carolina established its public schools in 1875, they provided for white and black children only. Whites expected Indians to attend schools with blacks or not attend school at all. In response, some Indians founded family-based, privately funded “subscription” schools, but historian Anna Bailey has shown that Indians also operated schools within the publicly funded “colored” school system. Each school was governed by a “school committee,” a group of three men who controlled admission to the school and made hiring and firing recommendations to the Board of Education. In some areas of the county with larger Indian populations, school committees were all Indian, but in other areas of the county, whites, blacks, and Indians served on school committees together. Bailey has also demonstrated that Indian and black children attended school together in some areas with smaller Indian populations. These interracial partnerships did not exist everywhere, however; some Indians apparently objected to admitting black children to their schools. In one district, the county Board of Education had to order an Indian school to admit “colored” children; when the school committee refused, the board renamed the district “colored,” although it had formerly been called “Indian.”6 Perhaps the board punished noncompliance by changing racial labels and classifying Indians as “colored,” an act that indicated the flexibility of racial categories in this time period and the tensions that ideas about race produced. Despite this instance of racial antipathy, Bailey’s research shows that to some degree, Indian, black, and white cooperation survived the Lowry War; Indians clearly worked with both blacks and whites in education, and their approach to these issues was decentralized and likely varied among different settlements. Through decisions about school attendance and control, they affirmed the centrality of kinship and settlement to Indian identity.

In 1885 Conservative Democrat Hamilton McMillan, a state legislator who represented Robeson County and lived in the town of Red Springs, recognized that the school issue presented an opportunity for gain in the contested political and social arena of Robeson County. McMillan successfully lobbied for legislation to recognize Robeson County Indians as a “tribe” of “Croatan Indians” and to create an Indian-only school system. The state instructed the Robeson County Board of Education to establish districts for Indian schools and to provide Indian children their share of the general school funds. The act created Indian-only school committees and allowed Indians to select their own teachers for their schools.7 McMillan’s law not only promised educational advancement; it also would contribute to Indian autonomy. Indians welcomed this segregation act because it affirmed their identity to non-Indians. By supporting Indian-only schools, McMillan divided the Indian and black vote, which had favored Republicans, and he helped secure Democratic political power and social supremacy.8 The multiracial political and educational coalition that surged during and after the Lowry War decayed when Indians chose to support the Democrats in exchange for their own schools.

The 1885 law recognizing the Indians of Robeson County as Croatans only partially institutionalized racial separation in Robeson County. Segregation mandated that Indians teach Indians, but prospective Indian teachers could not attend the state postsecondary institutions unless they agreed to enroll in black schools. In 1887 McMillan sponsored additional legislation to fund a Normal School to train Indian teachers. Indians wanted their own teachers because they functioned as role models for students, and their kin connections helped Indian parents feel secure that the teachers understood their children’s values. The legislature appropriated $500 to pay instructors for the school. Recognizing the value of a teacher-training institution for Indians, Rev. William Luther Moore, an Indian minister from Columbus County, raised the additional funds t...