- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

While battlefield parks and memorials erected in town squares and cemeteries have served to commemorate southern valor in the Civil War, Confederate soldiers' homes were actually 'living monuments' to the Lost Cause, housing the very men who made that cause their own. R. B. Rosenburg provides the first account of the establishment and operation of these homes for disabled and indigent southern veterans, which had their heyday between the 1880s and the 1920s. These institutions were commonly perceived as dignified retreats, where veterans who had seen better days could find peace, quiet, comfort, and happiness. But as Rosenburg shows, the harsher reality often included strict disciplinary tactics to maintain order and the treatment of indigent residents as wards and inmates rather than honored veterans. Many men chafed under the rigidly paternalistic administrative control and resented being told by their 'betters' how to behave. Rosenburg makes clear the idealism and sense of social responsibility that motivated the homes' founders and administrators, while also showing that from the outset the homes were enmeshed in political self-interest and the exploitation of the Confederate heritage.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Living Monuments by R. B. Rosenburg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Johnny Reb: Hero and Symbol

General Tennessee Flintlock Sash was an ancient Confederate veteran whom local society venerated and praised. On special occasions Sash, dressed in uniform, was loaned to a museum by his grand daughter, who took care of him, and carefully put on display, surrounded by other relics of the war. As schoolchildren passed by, they were afforded a rare opportunity to see (but not touch) a real, live Confederate veteran—and a general to boot! Yet neither was Sash a former general nor was he wearing his own uniform. In fact, he could hardly remember anything about the war, let alone the details of any engagement that he had supposedly witnessed. Moreover, he inwardly detested being forced to relive his part. Except for the pretty girls who occasionally paid attention to him, Sash could not have cared less for the ceremonial activities.

Not unlike Sash—a character in a story by Flannery Ohis word, General Jones kissed Scarlett OConnor1—thousands of Confederate veterans were dressed in uniforms, publicly exhibited, protected from harm, and required to play a role. They were residents of soldiers’ homes, “living monuments” to the South’s most sacred virtues of honor and chivalry. At these homes, not only schoolchildren, but southerners of all ages, gathered to celebrate and help relive the achievements of the past. The Confederate soldiers’ home served as simultaneously a place of refuge, a museum, a military camp, an artificial city, and a shrine.

As many as sixteen different Confederate soldiers’ homes were founded, and their collective histories span more than a century. The first homes were established during the 1880s and 1890s, a period of rampant ex-Confederate activity. In these two decades, at the same time that southerners organized and dedicated themselves to unveil monuments, write regimental histories, decorate cemeteries, preserve battlefields, and participate in reunion rituals—all in an effort to preserve the memory of Johnny Reb—a viable and discernible soldiers’ home “movement” developed.

Soldiers’ homes were built long before the 1880s. The Hôtel des Invalides, believed to be the first institution of its kind, was constructed in Paris by Louis XIV in 1670, and in 1682 the Chelsea military asylum was established by Charles II of England. In the United States, Congress first authorized an asylum in 1811 for veterans of the American navy; forty years later Senator Jefferson Davis introduced legislation that resulted in the founding of the U. S. Soldiers’ Home, with branches in Louisiana, Mississippi, Kentucky, and Washington, D. C. During the Civil War, the U. S. Sanitary Commission created temporary soldiers’ homes or lodges, and in the South private residences were converted into makeshift convalescent homes to meet the needs of wounded men. But these “soldiers’ homes” were relatively small-scale endeavors compared to the institutions established immediately after the war and during the next several decades in more than two dozen northern and western states to augment the newly created National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.2

Soldiers’ homes were not, then, uniquely southern institutions. In fact, there are striking similarities in the stories behind the creation and administration of Confederate homes and of their national counterparts. The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) and the Woman’s Relief Corps served as primary advocates of soldiers’ homes for Union veterans in much the same way that the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) championed homes for Johnny Reb. All but a few of the Union veterans’ homes established in as many as twenty-eight different states from Vermont to California were, like southern homes, founded during the 1880s and 1890s. The dedication of a veterans’ home for the “boys in blue,” as for the boys who had worn gray, was an important event, featuring bands and uniforms, campfires and speeches, drum corps and reunion tents. The “typical” state home for disabled and poor Union veterans was part military camp, part workhouse, part asylum, and part final refuge, just as it was for ex-Confederates. And national administrators and managers, no less than southern ones, adopted a paternalistic attitude toward their charges; at times worried that they were being overly repressive in maintaining discipline; fought ceaseless battles against inmates’ intemperance, filth, and unchaste-ness; earnestly sought to combat the debilitating effects of wounds and disease heightened by old age; and were generally reluctant to allow women to be admitted to the homes or to serve on governing boards. Moreover, based upon the available evidence, Union veterans who resided in the national homes apparently had much in common with their Confederate comrades. These old soldiers from both sides of the war were poor and semiskilled, and they were mostly single men who either had never married or had recently been widowed. In addition, they were told by their superiors to abide by rules and regulations, encouraged to attend worship services, warned about the evils of imbibing alcoholic beverages, and, above all, enjoined to conduct themselves as gentlemen or risk receiving a dishonorable discharge.3

At the same time, Confederate soldiers’ homes and those for Union veterans were different in at least two fundamental respects. First, despite yearnings by a group of well-meaning individuals, the southern homes never received monies from Uncle Sam. By contrast, in addition to regular legislative appropriations and occasional contributions from veterans’ groups, each state home that accommodated Union veterans received an annual per capita subsidy from the National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, a federal government agency. For example, beginning in 1888 the Wisconsin Veterans’ Home near Waupaca received $100 per year for every veteran admitted.4 By 1922 total federal funding for veterans’ homes had reached $777,757. A stronger financial base invariably eased the economic burden at homes caring for Union veterans—Southern homes always seemed to be strapped for funds—affecting in the long run both the level of service and the quality of care provided there. Furthermore, in accepting federal money, home officials were required ultimately to report to Washington and conform their operations to certain governmental standards. Confederate administrators were accountable to their individual state legislatures instead of a centralized bureaucracy responsible for coordinating veterans’ care in all southern states and therefore generally exercised greater autonomy.

Second, the Confederate homes, unlike national ones, excluded veterans of other wars. This difference had important consequences, too. Both Confederate and U. S. soldiers’ homes possessed symbolic as well as purely functional roles. Yet, because survivors of the Indian Wars and the Mexican-American War—and, in time, veterans from the Spanish-American War and World War I—were admitted to the national homes, they could not help losing much of their symbolic significance. No longer were they homes for veterans of the Union army exclusively. But the Confederate homes remained forever Confederate, even if their military character was altered when most of the veterans had died and widows and other female relatives were admitted as a matter of policy. While the functional significance of homes for both Confederate and Union veterans increased over time—as their populations aged and required greater custodial care—Confederate soldiers’ homes continued to serve a vital symbolic function for southerners of all ages even as national homes were losing their symbolic power and appeal.

Up until now, the Confederate soldiers’ home movement, which began in the 1880s, has received scant attention. William W. White’s standard work, The Confederate Veteran, devotes only four brief pages to the topic. Judith Cetina’s ambitious dissertation,“A History of Veterans’ Homes in the United States, 1811—1930,” apportions less than a dozen of nearly 500 pages to the Confederate homes of Louisiana and Maryland and the South Carolina institution for needy women. Only three concise summaries—concerning the Virginia, North Carolina, and Oklahoma homes—have appeared in print. Therefore, any attempt to treat several homes at once and to place them in their proper historical context will enhance our current knowledge and understanding of these homes.5

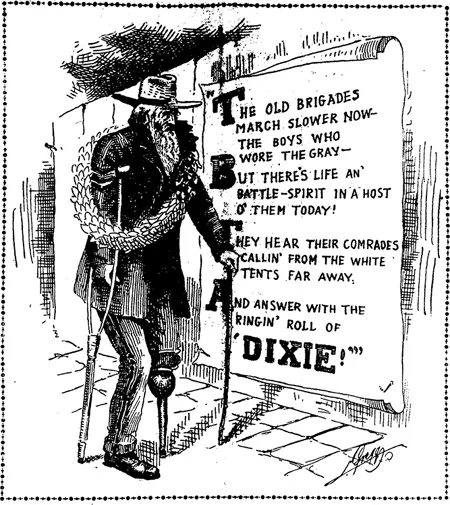

Images of Johnny Reb, like this one, helped inspire the establishment of homes for wounded, poor, but brave, ex-Confederates, (author’s collection)

Although not concerning themselves with the soldiers’ homes per se, at least two scholars have interpreted them within a larger framework. Charles Wilson views the Lost Cause as a conservative “cultural revitalization” movement, arguing that Lost Cause enthusiasts (particularly ex-Confederate organizations) feared that certain southern values were threatened and sought to safeguard those values by preserving or reliving the past. Preservation or revitalization, according to Wilson, took various forms: monument dedication, archival work, holiday and reunion rituals. Therefore, if Wilson is correct in identifying the appeal of the Lost Cause, Confederate soldiers’ homes were created as means of resisting progress and preserving tradition. In other words, the Confederate soldiers’ home was a manifestation of the struggle to reconcile “progress and tradition.”6 More recently, Gaines Foster has interpreted the “celebration” of traditional southern values by predominantly middle-class Confederate veterans’ groups in the late 1880s and early 1890s as a direct reaction to various social and political upheavals and tensions that gripped the South following the war. The rituals of this celebration, he points out, above all praised the common soldier—by building monuments or writing histories, by awarding pensions or establishing veterans’ homes—as a means of re-forrning society and promoting social unity7

An in-depth investigation of Confederate soldiers’ homes necessitates testing these prevailing interpretations. As this study reveals, the southern soldiers’ home movement cannot be isolated from other attempts by the public to memorialize Johnny Reb, and reactionary Lost Cause zealots (or even southerners in general) were not the only ones who took part in the movement. Although they founded soldiers’ homes of their own, Union veterans actively participated in the establishment of similar southern institutions. Also, at the forefront of the movement were southerners like Henry Grady, John B. Gordon, Lawrence “Sul” Ross, Francis P. Fleming, and Julian Shakespeare Carr, men who championed national as well as sectional values. Thus, Confederate soldiers’ homes cannot be viewed solely as another ritual for preserving a special southern identity but must be seen also as a vehicle for achieving sectional reconciliation.

As Gaines Foster has suggested, the Confederate soldiers’ home movement was, indeed, a class-specific reform movement. Predominantly middle-class members of society eagerly responded to the needs of indigent but “worthy” veterans by founding institutions and administering them; and it was this same group of people who consistently viewed their charges as objects of benevolent paternalism requiring comfort and care, as well as moral guidance and discipline. Camp Nicholls, the second soldiers’ home of Louisiana,8 for example, was made possible through the combined efforts of two strong veterans’ societies headquartered in New Orleans. Born during a period of intense political strife, the first of these organizations, the Association of the Army of Northern Virginia (AANV), was chartered in 1874, about the same time that more than a dozen different militia companies united to oppose the Radical Republican administration of Governor William P. Kellogg. The White League attracted to its ranks men with military backgrounds, many of whom were former Confederate soldiers. In September 1874 they handily defeated state troops commanded by, among others, General James Long-street, in what came to be known as the battle of Liberty Place, and forcibly removed Kellogg from office. The second organization, the Association of the Army of Tennessee (AAT), also had ties with the White League. Some men already belonging to the prestigious Washington Artillery joined the AAT when it was formed in 1877. Three years earlier the unit had fought alongside other militia groups during the battle of Liberty Place.9

In spite of the political activism of some members, both the AANV and the AAT, like most fraternal orders of the period, functioned primarily as benefit societies, preferring to identify themselves as “benevolent” and incorporating the word as part of their official names. Benevolence took two forms, one for members and another for nonmembers. Each association aimed to provide its dues-paying members and their dependents with assistance during personal and unavoidable crises: sudden unemployment, poverty, and “extreme cases of want and sickness.” When a member “in good standing” died, for example, he could count on his comrades to give him a proper and decent burial in the group tomb the veterans had paid for and erected.10 Like other fraternal organizations, the AANV and AAT in reality operated as exclusive social clubs rather than as fraternities open to all ex-Confederates. More than two-thirds (67.9 percent) of AAT members had proprietary or professional occupations. Influential men—attorneys, physicians, clergymen, merchants, and elected officials—also dominated AANV membership rolls. Each group established and originally enforced stringent membership guidelines: the association was opened to anyone of “good moral character” who had served honorably, subject to a two-thirds vote of the membership. The bylaws drafted by each organization permitted honorary memberships for local dignitaries, particularly leaders of other veterans’ organizations. Yet the same rules barred survivors of different Confederate armies from joining. As for needy veterans not belonging to a particular society—or those men entitled to membership by virtue of their military record but unable to afford to pay monthly dues—they had to look elsewhere for comradeship and assistance.11

Nonmembers, but comrades nonetheless, received second priority in the benevolent activities of the AAT and AANV. In response to the yellow fever epidemic that devastated New Orleans in 1878, each association created and maintained for many years veterans’ benefits and relief committees that supervised the distribution of funds and other donated items of clothing, food, and medicine to “worthy” recipients. In the depression era of the mid-1890s several prominent members of the AANV founded a job agency in order to assist able-bodied comrades (and their spouses and children) in finding work. Headed by James Y. Gilmore, a journalist, and Hamilton Dudley Coleman, a local plantation machinery manufacturer and dealer, the Confederate Veterans’ Employment Bureau of New Orleans published and circulated a small pamphlet containing the names, addresses, and occupations of scores of “exemplary and law-abiding” applicants.12 The two veterans’ groups sometimes coordinated relief activities as well. In one instance of such a dual effort, in 1880 they convinced state legislators to enact a bill providing either artificial limbs or cash payments for crippled ex-Confederates. Both societies continued to lobby successfully for similar legislation throughout the decade. Beginning in 1884, for example, owing largely to the efforts of the AAT and AANV, the state granted a quarter section of land to disabled and indigent Confederate veterans and widows. Another combined project a year earlier had resulted in the establishment of a soldiers’ home in New Orleans.13

Among the first veterans’ organizations to establish a home for the “invalid and infirm” were other ex-Confederates who comprised the Robert E. Lee Camp No. 1 in Richmond, Virginia. Formed in 1883, the group was primarily dedicated to “minister[ing] . . . to the wants of” dis...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter One: Johnny Reb: Hero and Symbol

- Chapter Two: Southern Poor Boys

- Chapter Three: The Sacred Duty

- Chapter Four: The Home That Grady Built

- Chapter Five: A Discipline for Heroes

- Chapter Six: Inside the Walls

- Chapter Seven: Twice a Child

- Chapter Eight: Patterns of Change and Decline

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index