![]()

FOLKLIFE

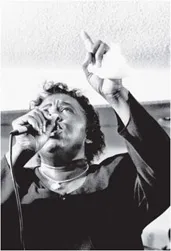

The spirit is high when Sister Lena Mae Perry strides to the front of the huge, gleaming church. Worshipers at the Western Assemblies Headquarters Building in rural Newton Grove, N.C., had already been offering praises for more than three hours. They had sung with the choirs, echoed the emcee’s exhortations, clapped to the quartets’ driving tempos, and shouted when the spirit led them to shout. Elegantly gowned grandmothers had leapt from the pews in the ecstatic steps of the holy dance; youthful fathers had rocked children to sleep to the sounds of passionate praise; and more than a few young boys—all dressed in sharp-looking suits, with silk ties slightly askew—had ably manned the drums while their parents sang at the church-front microphones. Now, as the electric guitar and bass played an understated riff, the churchgoers are ready to praise anew. It is Sister Perry’s turn to light the fires of exaltation.

Stately and commanding in her shimmering gold gown, the sixtysomething singer gazes over the congregation. These are her people, believers who know and share the ways of faith, worshipers who see themselves as part of the vast community of African American Christians who self-identify as “saints.” In the pews before her are teachers, computer programmers, restaurant owners, bricklayers, social workers, bulldozer operators, doctors, service workers, chefs, college students, and more. But occupation and life’s standing—as Sister Perry is quick to tell you—matter not in the community of faith. All are here to lift God’s praises, and that’s all that counts.

Cued by a glance from Sister Perry, the piano player gently steers the melody to the opening chords of the old hymn “Remember Me.” Sister Perry sings the opening words with a power that shakes the church, her low voice caressing each slowly voiced syllable. This is one of those “way back” hymns, a piece that Sister Perry remembers as being one of the first songs she ever heard. These memories seem to whisper across her face as she sings with eyes closed, fervently asking the Lord to remember her as she moves though life’s daily trials. “When you sing a song slow like that, people will sit and listen,” she later says. “The thoughts get to rolling over and over in their mind, as they remember what the Lord has brought them through. Those old hymns will stir up a congregation.”

And stir it does. Gentle cries of “Thank you, Jesus” and “Praise God” are soon floating through the church, buoyed by a chorus of quiet singing, hushed sobs, and soundlessly waved hands. This is clearly a song that means, a piece that draws its hearers together in a communion of feeling, spirit, and shared memory. Churchgoers speak of this experience as being “in one accord,” when the self finds sustenance in the sharing of the whole. Though Sister Perry certainly leads the moment, its many meanings find fullness not in her words, but in the spirits of those seated in the pews.

As the song ends, Sister Perry pauses to offer a few words of quiet testimony. Her voice quickens, however, as she introduces her second piece, the faster-paced “If You Can’t Help Me.” Instantly, churchgoers are clapping with the rhythm, enthusiastically pushing the tempo as they sing the song’s victorious refrain. If they knew the opening hymn from church, they know this piece from the radio; it was a gospel “hit” for the Philadelphia-based Angelic Gospel Singers in the 1980s and still gets frequent airplay on the area’s AM gospel stations. The song’s source, however, matters little to these believers. What is important is its message, a message of affirmation and persistence that clearly resonates with their lives. They too are “running by faith,” dodging earthbound obstacles to reach that heavenly “finishing line.”

“That song just relates to me,” asserts Sister Perry, reflecting on why she added this piece to her repertoire. “I’ve had those experiences, of people talking about me and blocking my way. And so have others. But where I sing it for one purpose, for someone else it might mean something different. But it still serves a purpose, whatever their situation. That’s why people like that song so much.”

This “liking” is everywhere evident in the church. The exuberant singing echoes off the building’s vaulted ceilings, while the rhapsodic clapping encourages the musicians to play with even more fervor. Once again, the congregation is on one accord. And Sister Perry—who clearly feels the shared spirit—smiles and sings on.

What does all this have to do with “folklife”? Why open an encyclopedia volume with a story about singing in church? And why open with this story, one that doesn’t particularly speak to popular understandings about the “folk”? The described scene, after all, is not exactly steeped in the old-time and traditional. And these certainly are the qualities that leap to mind when encountering the term “folklife.” Perhaps if the church were smaller and more intimate, with wood-framed walls and a humble sanctuary. Perhaps if the instruments were acoustic instead of electric. Perhaps if the congregation were a bit more working class, a bit more evidently “folky.” Perhaps if Sister Perry were wearing something plainer, something less sparkly. Perhaps if both of the songs were old, hearkening from an era that predated the taint of commercial production. And perhaps if Sister Perry had learned the second piece from other singers, rather than from the radio. Then this scene might more readily qualify as the common understanding of the term “folk.”

The passion of gospel singing, echoed by the congregation’s enthusiastic hand claps and calls of encouragement, in many ways exemplifies the communion of spirit, meaning, and community that lies at the heart of folklife. Southern churchgoers often speak of this communion as “coming to accord,” suggesting the particular moment when a singer’s intent and the audience’s appreciative understanding come together as one. North Carolina gospel singer Lena Mae Perry—like countless other singers in churches across the South—leads congregations toward this place of experienced unity virtually every weekend, reminding us that folklife is a vibrant, thriving, and fundamental feature of southern culture. (Photograph by Roland L. Freeman)

Of course, some aspects of the described scene do fit popular definitions of folkness. Perhaps foremost among these is the simple fact that these churchgoers clearly share a set of beliefs, a sense of style and taste, and a set of worship practices (from their clapped accompaniments and voiced praises to their silently waved hands). In this sharing, they constitute a community set apart from others who don’t occupy this same circle of aesthetics and faith. Is this enough to merit the mantle of folklife? Further, these features of set-apartness were likely learned through nonformal means; that is, they were probably conveyed through observation and conversation rather than through formal teaching. This too seems to be a favorite criteria of the popular definition. Taken together, do these qualities offer enough of a counterbalance to slide this performance under the rubric of “folklife”?

The best response to this question offers not a balancing tally as much as a refocusing of the query, a refocusing that leads away from issues of form and process and toward those of intent and meaning. We might well begin this process by listening again to Sister Perry’s descriptions of her songs. In both cases, she speaks of how the songs make her and her listeners feel. She foregrounds the emotions that the songs invoke, first pointing to passion and intensity and then grounding these experiences in deeper currents of felt significance. The passion is not an end in itself; Sister Perry says that she doesn’t sing merely to make people feel good. Instead, as she explains, the passion is a pathway to deeper meanings, an invitation to reflect, to remember, to connect.

Sister Perry sings with the knowledge that songs have this power. Her fellow churchgoers, in turn, share this understanding. Singing thus becomes an act of connection, a meeting of the singer’s intent and the listeners’ expectations. It is this coming together that yields the “one accord” of which churchgoers so often speak—an accord grounded in trust and mutual understanding, an accord that sizzles with significance. Those who experience this significance needn’t feel it as earthshakingly strong. The sizzle might be slight, felt only as the subtle comfort of familiarity or the passing flicker of cherished memory. Alternately, it might be intense, felt as a deep stirring of the spirit. (Such was clearly the case for the worshipers moved to tears during Sister Perry’s singing.) Whatever the experience—whether slight or strong—the sizzle of meaning is always profound, for it speaks to a connectedness that grounds the individual in the welcome embrace of community.

We might well describe “folklife” in terms of this accord, pointing to the countless ways of being and doing that craft the bonds of community. These ways need not be performed, as they were in Sister Perry’s case; they need not bear the stamp of artistry that one would expect when speaking about “folk songs,” “folk dances,” or “folktales.” More often than not, they are simply enacted, pursued as part of everyday life, engaged during work, worship, leisure, and play. Hence the focus on life in the term “folklife.” To speak of folklife is to speak of the ways that communities create, sustain, and celebrate their identities. And at the heart of this creating and sustaining—as is always the case when talk turns to matters of identity—is meaning.

This brings us full circle to the questions that opened this discussion, questions that challenged the suitability of Sister Perry’s story to open a volume on southern folklife. Those questions focused on the particularities of tradition and transmission, asking how Sister Perry learned the songs, why the setting was so patently modern, why the “community” encompassed so many social classes, even why the instruments were electric (and thus not sufficiently old-fashioned to warrant the designation “folk”). Notice that none of these questions speaks to measures of meaning foregrounded by the community in question. The churchgoers who sang and clapped and wept didn’t seem bothered by the newness of the building or the source of the songs; the communion they experienced did not seem to hinge on the nature of the instruments or the social status of the congregant sitting on the other end of the pew. The meanings that the churchgoers experienced transcended these matters, tacitly declaring their relative unimportance. What was truly important (as these churchgoers are quick to testify) was the feeling of shared community and the recognition that this sharing is grounded in a host of overlapping sharings, from beliefs, musical tastes, and ways of dressing to joint memories, forms of talking, familiar gestures, hairstyles, and so much more. Therein lie the meanings. And therein lies the best reason for including this moment under the rubric of “folklife.”

Of course, if you asked the congregation members about this designation, you would probably earn only blank stares. The term “folklife” is not a word in widespread use; indeed, other than those instances where it precedes the word “festival,” you will rarely hear it in everyday conversation. It is a word that lives largely in the rarefied world of academic study and in the productions and discussions of folklorists. This does not mean, however, that the term has little value beyond these narrow circles. As a broadly encompassing abstraction, “folklife” offers a way to recognize patterns of meaningful connectedness and similarity across widely divergent practices, performances, beliefs, and communities. The term “folklife” invites us to step back while stepping in, to discern broad patterns while exploring the particularities of expression in any given community. That community might be made up of the congregation of a sanctified church or the members of a synagogue; line workers in a textile mill or office workers in a high-tech pharmaceutical firm; friends who foxhunt together or knitters who gather for weekly meetings; an online chat group or the kids on a neighborhood playground; hip-hop emcees in freestyle competitions or participants in bluegrass picking sessions; Civil War reenactors or powwow drummers or matachines dancers; union members or masons; midwives or debutantes; even friends who get together in country stores, coffee shops, or fast-food joints to gossip, boast, tell stories, or simply pass the time. What matters is not the formality or informality of the ties that bind these folks together as groups, but rather the fact that they see themselves as group members. They recognize and enact their groupness. In so doing, they create and celebrate places of sharing and of shared meaning.

While these meanings rest with the group members, they are often opaque to those who are not members of these communities. This opaqueness, in turn, can all too easily invite misreading and misunderstandings on the part of outsiders. This process is an altogether familiar one. Not privy to the insider meanings, outsiders tend to read the external markers of a group’s identity—markers that often make themselves apparent in ways of dressing, talking, worshipping, playing, or eating—and then try to make sense of these differences. This sense making, in turn, typically entails coming up with “explanations” of these differences that fit within the outsiders’ way of understanding the world. Note that these “explanations” come not from group insiders but from the outsiders, who are the ones trying to understand the differences. This process might best be likened to fitting square pegs into round holes; sometimes the only way to make the pegs fit is to mangle them enough to force them into the unyielding circles. This mangling engenders the misunderstandings that so often characterize contact between communities of difference, misunderstandings that readily give rise to stereotypes. When contact between groups involves differences in power (as is frequently the case in the South), these misunderstandings all too often lead to mistreatment and exploitation.

The study of folklife has the potential to short-circuit this process of misunderstanding. It does so by drawing us into conversation with members of these disparate communities, inviting them to explain the meanings that are so often obscure to outsiders. Their words, their passions, their understandings thus become part of the dialogue. At the same time, folklife study offers us insights into shared patterns of creating identity, patterns that make themselves evident in realms as diverse as the layout of local cemeteries and the foods served at family gatherings. Such patterns often transcend community boundaries; understanding them allows us to “read” unfamiliar situations with greater sensitivity and to ask questions of community members that we might not have otherwise thought to ask. The goal, in the end, is to foster fuller understanding across what can initially seem like chasms of difference and become aware of the role that each of us plays in keeping these misunderstandings alive.

This volume pursues this goal of building understanding by exploring the diversity and differences that constitute life in the South and offering readers openings for conversation and further inquiry. The volume’s focus on folklife promises coverage of an impossibly broad range of practices, beliefs, and ways of being. Indeed, one could argue that folklife encompasses virtually every important dimension of what it means to be southern, for folklife speaks to all of those places where people in communities craft meaning. Though these places are clearly too plentiful to catalog in a single volume, we nonetheless offer a starting place, providing a selective set of glimpses that will hopefully invite readers to probe further and ask new kinds of questions when they encounter practices different from their own.

The “Life” in Folklife. Where does meaning happen? At first glance, the question seems too abstract, too vague, to even consider. Yet if we narrow the context and ask where meaning happens in communities, then it suddenly makes a bit more sense. When community becomes both the frame for and the agent of meaning making, we start to step into the realm of folklife. And as we so step, some of these places of meaning quickly offer themselves for consideration. This is certainly true for the South’s many performance traditions, which self-consciously meld significance and passion in the fires of artistry. These are traditions that speak both inward to the community that creates them and outward to the communities that encounter them; as such, they often serve as clear markers of group identity. One need only look to gospel, bluegrass, southern hip-hop, Cajun, country, alt-country, old-time string band, norteño, southern soul, or any of the South’s many other vibrant musics to recognize the power that performance traditions can hold. By the same token, one could look at dancing and its many exuberant analogues for telling examples of performed intensity. The intricacies of buckdancing, the drama of collegiate stepping, and the deep subtleties of dancing at the Cherokee Green Corn Ceremony, for instance, certainly testify to the range and performative power of dance in the South, while the strutting of second liners in New Orleans street processions, the acrobatics of high school cheerleaders, and the high-stepping glories of African American collegiate marching bands just as powerfully speak to the rich worlds of dance-related movement. Folklife also encompasses performances of the crafted word, whether voiced as tales, testimonies, stories of personal experience, sermons, poetry, or even the perfectly phrased pickup line. In addition to standing alone, these familiar performance realms—music, dance, movement, and artful talk—often come together in community-based dramas, which range from drive-through nativity spectacles to Halloween-time “Hell House” productions and womanless weddings.

Performances, of course, need not offer themselves with the public immediacy of a chitlin-circuit dancer or a tale-spinning raconteur. Many are far more subtle, imparting meaning not in the intensity of a sparkling moment but in the quietude of time’s passage. This is particularly true for those performances that yield crafted objects—artful things that hold and communicate the passion invested in them by their creators. Though perha...