eBook - ePub

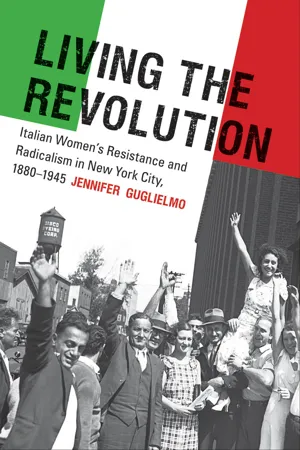

Living the Revolution

Italian Women's Resistance and Radicalism in New York City, 1880-1945

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Living the Revolution

Italian Women's Resistance and Radicalism in New York City, 1880-1945

About this book

Italians were the largest group of immigrants to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, and hundreds of thousands led and participated in some of the period's most volatile labor strikes. Jennifer Guglielmo brings to life the Italian working-class women of New York and New Jersey who helped shape the vibrant radical political culture that expanded into the emerging industrial union movement. Tracing two generations of women who worked in the needle and textile trades, she explores the ways immigrant women and their American-born daughters drew on Italian traditions of protest to form new urban female networks of everyday resistance and political activism. She also shows how their commitment to revolutionary and transnational social movements diminished as they became white working-class Americans.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Living the Revolution by Jennifer Guglielmo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Labour & Industrial Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Women’s Cultures of Resistance in Southern Italy

Si viju lu diavulu non schiantu (If I see the devil I do not run).

—Calabrese women’s song

A wave of popular unrest washed over Sicily at the close of the nineteenth century. In town after town, peasants mobilized labor strikes, occupied fields and piazzas, and looted government offices. While the island had a long history of revolt, this marked a new era of social protest. For the first time, women led the social movement and infused the struggle with their own mixture of socialism and spiritualism.

The activity began in the autumn of 1892, in the towns surrounding Palermo, in the northwestern part of the island. In Monreale, women and children filled the central piazza shouting “Down with the municipal government! Long live the union!”1 After attacking and looting the offices of the city council, they marched toward Palermo crying “We are hungry!” waving banners with slogans connecting socialism to scripture. In Villafrati, Caterina Costanzo led a group of women wielding clubs to the fields where they threatened workers who had not joined the community in a general strike against the repressive local government. In Balestrate, thousands of women dressed in traditional clothes and also armed with clubs marched through the streets, demanding an end to government corruption. In Belmonte, Felicia Pizzo Di Lorenzo led fifty peasant women through the town and then gathered in the palazzo comunale, demanding the abolition of taxes, the removal of the mayor, and the termination of the city council. Three days later, when the crowd had grown to six hundred women and men, the mayor and his police broke up the demonstration and arrested the most vocal protestors.

In Piana dei Greci, thirty-six women were arrested after they occupied and then destroyed the municipal offices, throwing the furniture into the streets.

Women with amphorae, Carloforte, Island of San Pietro, Sardinia, 1913. Alinari Archives, Florence, Italy.

Soon after the uprising, close to one thousand women there formed a fascio delle lavoratrici (union of workers). The word fascio, “meaning bundle, or sheaf (as in sheaf of wheat),” in this case referred to “a sodality of peasants, miners, or artisans.”2 They celebrated the founding of the group as they would a religious festival, with music and food, and wove their political and spiritual ideologies together in their speeches. In the words of one woman, “We want everybody to work as we work. There should no longer be either rich or poor. All should have bread for themselves and their children. We should all be equal.... Jesus was a true socialist and he wanted precisely what we ask for, but the priests don’t discuss this.”3

News of the uprisings traveled quickly. Within days, government officials and newspaper reporters arrived from the mainland to witness the disturbances. Adolfo Rossi, a government official who would become the Italian commissioner of emigration, was one of the first to appear on the scene, and his observations circulated in the Roman newspaper La Tribuna in the fall of 1893. From Piana dei Greci, an epicenter of activity, he wrote: “The most serious sign is that the women are the most enthusiastic.... Peasant women’s fasci are no less fierce than those of the men.” In some areas, “women who were once very religious now believe only in their fasci,” and “in those areas where men are timid against authority, their wives soon convince them to join the movement of workers.”4 When the government accused the newly formed Italian Socialist Party of orchestrating the rebellion, party leader Filippo Turati argued that the movement was indigenous and rooted in popular solidarity: “The women, whose role in igniting the insurrection is well known, have abandoned the church for the fasci and it is they who incite their husbands and children to action.”5

The Italian government responded swiftly. On 3 January 1894, Prime Minister Francesco Crispi (a Sicilian himself) called for a state of siege and sent forty thousand military troops to the island to “contain the socialist threat.”6 Movement leaders and participants were arrested, beaten, and gunned down in the streets or executed in prison. Yet agitation continued to spread across the island and to the mainland. As popular unrest moved from the South to the North, women continued to play a critical role, leading street demonstrations and riots in small villages and towns throughout Calabria, Basiciliata, and Puglia and in the cities of Rome, Bologna, Imola, Ancona, Naples, Bari, Florence, Milan, and Genoa. Across Italy, workers in the emerging industrial cities joined with peasants to demand a complete restructuring of society based on socialist principles and filled streets chanting “Long Live Anarchy! Long Live Social Revolution!”7 In October, Crispi ordered the suppression of all socialist and anarchist groups. A four-year repressive campaign culminated in the fatti di maggio of 1898—the massacre of eighty demonstrators in Milan.8 By 1900 most of Italy’s peasantry and workers had experienced or heard of this kind of revolutionary struggle. It was in this climate that mass emigration from Italy took place.

THIS HISTORY of women’s revolutionary activity was foundational to Italian women’s cultures of resistance in early twentieth-century New York City. Scholars often label this activity as prepolitical and “primitive” because it began outside of the formal political spaces of trade unions and political parties.9 Yet it was this kind of activity that launched modern working-class movements in Italy and throughout the diaspora. When women turned to building anarchist women’s groups, industrial labor unions, and grass-roots neighborhood coalitions, they drew upon traditions of civil disobedience and community-wide revolts that were independent of formal organizations yet firmly rooted in popular solidarity. In fact, these methods remained fundamental to how Italian women expressed their discontent during the first half of the twentieth century, at home and abroad.

This chapter explores the social and cultural worlds that gave shape to this kind of collective consciousness and action. As with other impoverished women around the world, their politics emerged from daily struggles to care for family, friends, and neighbors. It grew out of daily confrontations with authority and the many indignities brought about by industrial expansion, mass emigration, and national centralization under northern Italian rule. But it also emerged from female social worlds that provided women with a certain autonomy to craft methods of subterfuge.

This new era of peasant women’s political activism occurred at precisely the same time that emigration from Italy began to reach mass proportions. As large numbers of men left in search of work, women’s responsibilities expanded. The female worlds that developed during men’s prolonged absences provided women with the space to articulate grievances, critique authority, and challenge oppressive conditions in new ways. While women continued to struggle with one another and with returning men over issues of power and authority, they also asserted for themselves more autonomous roles in their families and communities.

The peasant uprisings of the 1890s grew out of these worlds and provided a basis from which women crafted a distinctly antinationalist, socialist, and anarchist movement that was informed by their own unique blend of class consciousness and spiritualism. To the northern elites attempting to quell such resistance, southern Italian peasant women came to symbolize the changes they feared the most: as unruly peasants, relatively independent women, and political subversives, southern Italian women routinely challenged the attempts by landowners, state officials, religious leaders, and other authorities, to control and subdue them into model subjects. This struggle occurred not only in their piazzas and fields but also in places they had little access to—in the writings and exhortations of the upper classes, who worked tirelessly to cast the women in disparaging ways in order to justify their repression, dispossession, and poverty. The now familiar tropes of Italian peasant women as submissive, ignorant victims can be traced directly to Italian bourgeois attempts to possess such insurrectionary women in order to secure their own social and economic position.

Transnational Lives

In 1915 the British travel writer, Norman Douglas, reflected on his journey to the southern Italian province of Calabria: “A change is upon the land,” he wrote, “the patriarchal system of Coriolanus, the glory of southern Italy, is breaking up.” He attributed this rupture to mass emigration, noting that across the region there was “a large preponderance of women over men, nearly the whole male section of the community, save the young and the decrepit, being in America.”10 His words echoed the concerns of the new state, which reported that throughout the province of neighboring Caserta, the population consisted only of women, infants, and the very old.11 Two decades later, when Carlo Levi was banished by the fascist government to an impoverished agricultural village in Basilicata for his resistance to the regime, he similarly noted, “The men have gone and the women have taken over... a matriarchal regime prevails.”12

The rising numbers of women living on their own drew attention precisely because transnational migration was dramatically transforming life in southern Italy. Between 1870 and 1970, more than twenty-six million Italians migrated to other lands. As many as 60 to 80 percent of the migratory population were young men—peasants, artisans, and unskilled workers—who moved regularly in search of work. Several decades of internal movement from rural areas to cities and at least four centuries of migration throughout the Mediterranean and across the Alps into Switzerland, France, and Germany preceded the mass migrations. But by the 1890s, such movement stretched across continents and oceans, as Italians traveled to and from urban centers such as New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, Montreal, Marseilles, São Paulo, and Buenos Aires, as well as mining and agricultural regions, where they could earn enough cash to send wages home. The years between Italian national unification in 1861 and the First World War witnessed the largest exodus, as fourteen million people emigrated from Italy.13

The majority of Italy’s migrants came from the poorer and more agricultural southern provinces of Sicily, Campania, Basilicata, and Calabria and from Veneto in the northeast. Most of those who found their way to the United States came from the South, and they migrated for many of the same factors that fueled their revolutionary movements. In their own testimonies, migrants spoke of intense poverty when reflecting on their motivation to leave.14 Yet Italians had lived amid poverty, a stagnant economy, unsustainable population growth, devastating diseases like malaria, and natural disasters such as drought and earthquakes for most of the nineteenth century. The formation of the Italian nation and its unjust system of taxation on the South’s peasantry and violent repression of resistance movements compelled migration. But the movement of industrial capitalism from northern Europe to the United States was the primary reason southern Italians crossed the Atlantic. Most went to the United States, with smaller numbers going to South America (mostly Brazil and Argentina), Africa, Australia, and the rest of Europe. Many men crossed the Atlantic several times and worked in different locales and countries in one lifetime, and at least half of those who went to the United States ultimately returned to Italy.15

Because migrants depended on their families and friends for advice and help about work opportunities abroad, they often traveled the beaten paths of kin and friends from their hometown. Most migrants could not afford to bring their families and sustain them abroad because their jobs were too marginal and precarious. Rather, they sent a portion of their wages home. These earnings not only enabled whole families to survive but were also essential to the economic development of the Italian state. Records show that “remittances to Italy soared from 13 million lire in 1861 to 127 million lire in 1880 and then to 254 million yearly after 1890 and 846 million yearly after 1906. So large was the cash inflow that it ended Italy’s negative balance of foreign trade by 1912. Emigration had become one of Italy’s largest industries.”16

Women and Migration Culture

During these years of mass exodus, women participated in transatlantic migration in fewer numbers. Between 1896 and 1914, women composed only 20 to 28 percent of Italian emigration.17 Italian women’s experience of migration was thus most often in the homeland, especially in the years before World War I. But the mass departure of men profoundly altered women’s lives as they took over more responsibilities to sustain the home base in Italy. Anna Parola’s memories of her childhood confirmed impressions of female-dominated village life: “Many women were like widows, with husbands far away,” she recalled. “Eh, our need for bread ruled us.”18 Sociologist Renate Siebert writes that for the women of this generation, transatlantic migration caused “a tragic breaking.” In the interviews she conducted with dozens of women from Calabria and Basilicata, she heard of long separations from fathers, husbands, brothers, and lovers and the pain women experienced when contact was lost or when men died abroad and were laid to rest without family present. “I wish I could’ve been a bird,” one woman recalled, “so I could have flown back and forth between here and there, to be with everyone.”19

Because seasonal labor migration was the primary strategy in which Italians confronted the emergence of a capitalist world economy, transnational families, cultures, and identities became a way of life even for those who never left the homeland. For several generations, kin networks, political cultures, friendships, budgets, and dreams transcended national borders and connected continents. Even though women were separated from the men in their families for long periods, they remained linked to those abroad. In fact, in the years between 1870 and 1914, some “male work camps and rural Italian villages had more communication with each other than with the national societies that surrounded either.”20 Both women and men viewed migration as a temporary but necessary measure to improve a family’s economic and social position. As a result, women came to occupy a central position in the international family economy by maintaining the transatlantic household and the many social networks that...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- LIVING THE REVOLUTION

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Women’s Cultures of Resistance in Southern Italy

- 2 La Sartina (The Seamstress) Becomes a Transnational Labor Migrant

- 3 The Racialization of Southern Italian Women

- 4 Surviving the Shock of Arrival and Everyday Resistance

- 5 Anarchist Feminists and the Radical Subculture

- 6 The 1909–1919 Strike Wave and the Birth of Industrial Unionism

- 7 Red Scare, the Lure of Fascism, and Diasporic Resistance

- 8 Community Organizing in a Racial Hall of Mirrors

- Conclusions

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index