![]()

1 DISCONNECTED THREADS

Fifty years after Pickett’s Charge, survivor D. B. Easley of the 14th Virginia finally admitted he had not seen very much of his regiment’s most famous assault. He had become “so engrossed with his part of a fight” that he recalled “very little else.” In apologizing for the haziness of his memory, he conceded an even more telling point: in the heat of battle, a soldier “fails to note all he does see.”1 Offering an equally important caveat, a Pennsylvania captain explained that many soldiers could not describe the chaos of combat, so they filled their letters, diaries, and official reports with exaggerations, fabrications, generalizations, or laconic dispassion. He feared that despite the efforts of conscientious historians “to weave a symmetrical whole from such disconnected threads,” they really preserved only a few bits of any military action, even one so dramatic as the great charge at Gettysburg on July 3,1863.2

A battlefield, according to military historian S. L. A. Marshall, is indeed “the lonesomest place which men share together.”3 Each soldier’s perceptions of what he saw or did in combat—or what he thought he saw or did—became individualized sets of memories. Moreover, such personal recollections are very selective. No soldier recalls every action he takes or every observation he makes in battle, argues historian Richard Holmes, because “the process of memory tends to emphasize the peaks and troughs of experience at the expense of the great grey level plain.”4 Those peaks and troughs provide the disconnected threads of experience the Pennsylvania captain described. Only the most exceptional events, even on this momentous day in American military history, were likely to leave lasting marks in the soldiers’ memories.

What did the survivors of that day tell us? Immediate postbattle musings offer glimpses of the horrific clash of arms. Collectively, however, they represent only a set of remarkable moments. These fragments of memory, as historian C. Vann Woodward has asserted, provide “the twilight zone between living memory and written history” that becomes the “breeding ground of mythology.”5 All too often, however, this mythology wears the mantle of “history,” and it is the perpetuation of this kind of record—written by the “eye who never saw the battle”—that Lieutenant Haskell dreaded.

What do those fragments tell us about what happened between Seminary Ridge and Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 3, 1863? They tell us many important things, and not all of them are obvious to the best scholars. Historians often miss one particularly important point about that day: thousands of soldiers marched away from Gettysburg with no lasting memory at all of the great charge of July 3. Pvt. Samuel A. Firebaugh of the 10th Virginia recalled his own tough fight on Culp’s Hill early that same morning as “the hardest contested battle of the war, lasting 6 hours” but dismissed the assault that afternoon with “Hill attacked on the right.”6 Col. Moses B. Lakeman of the 3rd Maine, after a hard fight at the Peach Orchard on July 2, summed up the next day with a few unspectacular observations: “Went to support of Second corps; no casualties. Rained at night. Enemy completely repulsed in our front all day. Commanding brigade.”7 The grand assault left no mark at all in the memories of the thousands of Gettysburg’s survivors who played no part in the attack or its repulse.

More interesting, of course, are the memories of soldiers who did participate in the event. Honest soldiers, such as Sergeant Easley, realized that they just did not see enough of the fighting on July 3 to explain very much about it. As a Pennsylvania soldier suggested, “None but the actors of the field can tell the story” of a battle, and even then, “each one can tell of his own knowledge but an infinitisimal part.”8 This truth behind these veterans’ observations compels both explanation and appreciation.

First, both the linear formations the armies used and the sheer numbers of soldiers involved in the fight on each side that day limited each combatant’s field of vision. One of Davis’s Mississippians best described the problem to his general a few years later: “I was very much like the French Soldier of whom you sometimes told us, who never saw anything while the battle was going on except the rump of his fat file leader.”9

In addition, the irregular terrain on the field of the great charge also limited what each soldier could see of the day’s action. The physical conformation of the July 3 battlefield was—and still is—deceiving. Then, as now, trees, patches of underbrush, and rock outcroppings dotted the fields and slopes. The front of Webb’s brigade stretched only several hundred yards, yet one man of the 72nd Pennsylvania later wrote that “those of us who were with the rest of the brigade knew nothing of the Sixty-Ninth [Pennsylvania], except as we heard their cheers and the crack of their rifles” because they were “partly concealed from view by the clump of trees.”10 The land between Seminary and Cemetery Ridges rolls gently, often dipping low enough to hide and shelter advancing soldiers. A low finger of ground jutting westward from the area around the Angle and the clump of trees toward the Emmitsburg Road, a subtly significant terrain feature largely unnoticed in 1863 and seldom noted today, effectively cut the battlefield in two. This subtle ripple cut the lines of sight along the lines of command responsibility: Pettigrew and Trimble fought Hays north of it, Pickett fought Gibbon south of it. Only a few soldiers saw much of both clashes. Smoke and the sheer number of horses and men on the field also made it difficult for any single individual to see much that day.

While limitations in visual contact circumscribed what any one man actually saw of Pickett’s Charge, Easley’s assertion that a soldier in the heat of combat “fails to note all he does see” deserves even more explanation. If a soldier set in memory only certain peak experiences and left the troughs unrecorded, what factors determined what would be remembered?

Most soldiers who took part in the fight on July 3 had seen combat before, and those experiences shaped perceptions now. North Carolina artilleryman Joseph Graham watched Southern infantrymen look out over the valley and heard them say: “ ‘That is worse than Malvern Hill.’”11 After the fight ended, Pvt. J. L. Bechtel of the 59th New York wrote: “Antietam was nothing compared to it.”12 The battle at Fredericksburg the previous December supplied many soldiers with the most obvious point of comparison. Capt. Henry L. Abbott watched the advancing Confederates and knew his men “would give them Fredericksburg.”13 Sgt. Alex McNeil of the 14th Connecticut bragged that his regiment “paid the Rebels back with Interest, for our defeat at Fredericksburg.”14 On the day after the great charge, Capt. J. J. Young of the 26th North Carolina wrote that “it was a second Fredericksburg affair, only the wrong way.”15

Some veterans knew that they lost more than physical vigor when the adrenaline rush of battle waned. They could forget much of what they saw or did. In times of extreme stress such as that induced by combat, argues Richard Holmes, the human brain only “records clips of experience, often in erratic sequence.”16 Lieutenant Haskell clearly understood something about the process of memory when he warned his brother not to expect to learn much about the fight from the postbattle accounts of senior officers: “The official reports may give results as to losses, with statements of attacks and repulses; they may also note the means by which results were attained, which is a statement of the number and kind of forces employed, but the connection between means and results, the mode, the battle proper, these reports touch lightly.” Even Haskell did not claim to write anything more than “simply my account of the battle.”17 Veterans admitted that in official reports—and in histories based on them—“much of the planning and more of the doing has been omitted.”18

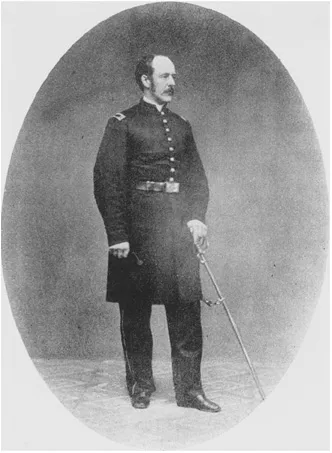

Lt. Frank Aretas Haskell, General Gibbon’s aide, who understood that his long narrative of the events of July 3 was just one man’s story, not history (Massachusetts Commandery, MOLLUS, USAMHI)

Historians have been slow to appreciate what Haskell and other veterans understood. The letters and diaries of veteran soldiers, far from providing concrete evidence of “the doing,” reveal that much of “the doing” had become routine. Thus, they tell very little about the fighting that scholars seek to describe. By 1863, veteran Pvt. William Hatchett of the 22nd Virginia Battalion could sum up the great charge at Gettysburg in a single sentence: “The last day which was the 3d we charged across an open field about a mile while they played on us with grape and cannister very heavy.”19 Even many longer accounts, such as that of the 34th North Carolina’s Lt. Burwell T. Cotton, reveal few more specifics about “the doing” than the official reports of which Haskell complained: “[We] charged them through an open field 1½ miles to their breast works. They threw shells, grape and canister as thick as hail. When we got in two hundred yards of them the infantry opened on us but onward we pressed until more than two thirds of the troops had been killed, wounded and straggled. Our lines were broken and we commenced retreating. A good many surrendered rather than risk getting out. They captured four flags in our brigade leaving only one. We lost four killed dead on the field and some six or seven wounded.”20

Doubtless Cotton and many others who survived July 3 agreed with a Vermont veteran who wrote, “Much history was made on this charge that can never be known, and much, though seen and realized that can never be adequately described!”21 Their reticence sprang from several sources, and a tendency to ignore the routine is only one of them. As Paul Fussell argues, the English language contains substantial numbers of words with sufficient power to convey images of destruction, violence, and death. Civil War soldiers simply did not use them very much, in part, it seems, from a concern about propriety and gentility.22 They apparently appreciated the truth behind Fussell’s rhetorical question: “What listener wants to be torn and shaken when he doesn’t have to be?”23

More to the point, however, many veteran soldiers had tired of trying to explain combat to those who could not comprehend its horrors. “Every war begins as one war and becomes two, that watched by civilians and that fought by soldiers,” historian Gerald Linderman has argued.24 Just before the battle, Union general Alpheus S. Williams explained the difference to family at home: “No man can give any idea of a battle by description nor by painting.” In graphic prose, he commented on the crashing roll of muskets, the thud of cannon balls as they thud through columns of human bodies, and “the ‘phiz’ of the Minie ball.” He advised that “if you can hear and see all this in a vivid fancy, you may have some faint idea of a battle,” but you still had to “stand in the midst and feel the elevation which few can fail to feel, even amidst its horrors, before you have the faintest notion of a scene so terrible and yet so grand.”25 Thus, just after July 3, a soldier from Maine could describe graphically the valley just south of the main thrust of Pickett’s Charge and still warn his correspondent that even “after what I have written you have no idea of the s[c]ene. . . . You look at it on too small a scale.”26 When veteran survivors of Pickett’s Charge sat down to write about July 3, then, they recorded highly selective impressions framed largely by previous experiences and personal notions of what their audiences either wanted to hear or could comprehend.

In any case, no matter what kind of language they employed—the unadorned, unemotional prose of Lieutenant Cotton or the more emotionally charged narrative of Lieutenant Haskell—soldiers wasted little time reflecting on the troughs of their experience. They recalled little of what they perceived to be routine, ordinary, or unexceptional, and although their contemporaries on the homefront (and subsequent historians) have not always understood this fact, most of what the combatants did before, during, and after the great charge at Gettysburg fit into these categories. What was expected of them on July 3 differed little from what had been required of them on previous battlefields.27 In the end, only four elements of this day’s work truly impressed the survivors as exceptional and worthy of special notice: the preassault cannonade, a few specific elements of the Confederate advance, the desperation and chaos at the Angle, and the high cost of such decisive results. About “the doing” of the rest of the charge, they told us remarkably little; yet most narratives of July 3 are built on these disconnected threads.

What did the soldiers recall of these four peak experiences? To begin, most soldiers, except for those directly caught up in the firefights near Culp’s Hill and Spangler’s Spring, began their written accounts of July 3 with the great artillery bombardment. At that mom...