![]()

Chapter one

The Gray Zone

An Introduction to Thomas Thistlewood and His Diaries

[A] Good Ship and easy gales have at last brought me to this part of the New World. New indeed in regard of ours, for here I find everything alter’d.... Britannia rose to my View all gay, with native Freedom blest, the seat of Arts, The Nurse of Learning, the Seat of Liberty, and Friend of every Virtue, where the meanest swain, with quiet Ease, possesses the Fruits of his hard Toil, contented with his Lot; while I was now to settle in a Place not half inhabited, cursed with intestine Broils, where slavery was establish’d, and the poor toiling Wretches work’d in the sultry Heat, and never knew the Sweets of Life or the advantage of their Painful Industry in a Place which, except the Verdure of its Fields, had nothing to recommend it.—Charles Leslie, A new and exact account of Jamaica

A Year in the Tropics

On 24 April 1750 at about noon, the Flying Flamborough docked at Kingston, Jamaica, after a long and troublesome voyage from London. Aboard was Thomas Thistlewood, age twenty-nine, the second son of a tenant farmer from Tupholme, Lincolnshire. Having failed to establish himself as a farmer in his home district, he had resolved to seek his fortune in the wider world. A trip to India as a supercargo on an East India ship had come to nothing. By late 1749, he had decided to set off for Jamaica.1 His baggage was not impressive. After paying for his passage, he had £14 18s. 5d. He hoped to supplement this small sum by selling “36 cases of razors” he had bought from a merchant in Ghent, which were worth £28 16s. and had been “made over to Mr. henry Hewitt of Brompton in lieu of £25 and its interest at 5% till paid.” He also had a promissory note of £60 from his older brother, William, which was all that remained of his inheritance from his deceased parents. In addition, he brought a bed; a liquor case with arrack, Brazilian rum, and Lisbon wine; two large sea chests crammed with books and four pictures, including “a very fine print of ye pretender, bought at Ghent”; surveying instruments; kitchen gear; mementos from his trip to the Orient; and an impressive collection of clothes that included nine waistcoats in various fabrics and colors. Most important for our purposes, he took with him a “Marble cover’d book for a journal.” Through this “Marble cover’d book” and thirty-six others just like it, we are afforded a rare entrée into the life and times of an ordinary man in an extraordinary society.

Thistlewood was no stranger to exotic locales. Nevertheless, the Caribbean presented him with novel sights and sounds. On a brief stopover in St. John’s, Antigua, he ventured into town with a fellow passenger to see “a pretty piece of modern architecture” that was to be the state house and spent “6d. which here is 9d.” at a rum house. He was not impressed. St. John’s was “an indifferent sort of place; streets rugged and stony and everything dear.” He visited a slave market, where he saw “yams, cashoo apples, guinea corn, plantains &c.” and first encountered West Indian slaves—“black girls” who “laid hold of us and would gladly have had us gone in with them.” Kingston was more agreeable. It was larger, with “24 ships ... and other craft in abundance” in the harbor.2 He visited two of the oldest residents of Kingston—the eighty-one-year-old William Cornish, who had been in Kingston since at least 1700, and the Reverend William May, rector of Kingston Parish since 1722, who gave him advice about how to survive—drink only water and eat lots of chocolate. He also started to learn about the culture of the majority of the inhabitants of his new land. He went “to the westward of the Town, to see Negro Diversions—odd Music, Motions &c. The Negroes of each Nation by themselves.”3

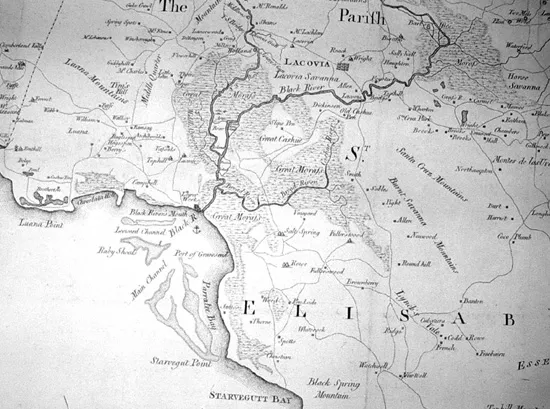

He learned even more when he traveled to Savanna-la-Mar in Westmoreland Parish in the southwest corner of the island. Within hours of arriving at noon on Friday, 4 May 1750, he was offered a job as an overseer on one of the properties of wealthy sugar planter William Dorrill. Dorrill lent him a horse, gave him a meal, and let him stay at his plantation, “ready to succeed his overseer who leaves him in about two months.” As it turned out, Dorrill’s position did not become vacant until September 1751. In the meantime, Thistlewood accepted a position from another wealthy planter, Florentius Vassall, as pen keeper at Vineyard Pen (“pen” is a Jamaican term for a property producing livestock or garden produce) in neighboring St. Elizabeth Parish on 2 July 1750. In the two months he lived at Dorrill’s, however, he began to understand the extent to which white dominance rested on naked force. Twelve days after Thistlewood’s arrival in Westmoreland Parish, Dorrill meted out “justice” to “runaway Negroes.” He whipped them severely and then rubbed pepper, salt, and lime juice into their wounds. Three days later, the body of a dead runaway slave was brought to Dorrill. He cut off the slave’s head and stuck it on a pole and then burned the body. These lessons on the necessity of controlling slaves through fear and violence were reinforced at Vineyard Pen. In mid-July 1750, less than two weeks after becoming pen keeper at Vineyard, he watched his first employer, the scion of one of the richest and most distinguished families on the island, give the leading slave on the pen, Dick, a mulatto driver, “300 lashes for his many crimes and negligences.” In the nearby town of Lacovia on 1 October, he “Saw a Negroe fellow named English ... Tried [in] Court and hang’d upon ye 1st tree immediately (drawing his knife upon a White Man) his hand cutt off, Body left unbury’d.” Given these examples, it is not surprising that Thistlewood also maintained his authority with a heavy hand. On 20 July, already convinced that his slaves were “a Nest of Thieves and Villains,” he whipped his first slave. He gave Titus, a slave who harbored a runaway, 150 lashes on 1 August.4

The relationship between whites and blacks was fraught but involved a significant degree of close interaction. During his first year in Jamaica, Thistlewood lived in a primarily black world. Between November 1750 and February 1751, he saw white people no more than three or four times.5 On 8 January 1751, Thistlewood recorded that “Today first saw a white person since December 19th that I was at Black River.” The forty slaves at Vineyard educated Thistlewood in Jamaican and African ways. Dick, the slave driver, introduced him to gungo peas (which were used in soup and served with rice) and slave medicinal

Thistlewood’s first post was at Vineyard Pen, marked on this 1763 map as on the southern edge of the Great Morass in southwest St. Elizabeth Parish, a few miles inland from the hamlet of Black River. From Thomas Craskell and James Simpson, Map of the County of Cornwall, in the Island of Jamaica (London, 1763).

remedies. Other slaves taught him how to cure sores and comfort irritated eyes. They told him about Jamaican plants and animals and adaptations of African recipes they had developed in enslavement. His diaries in the first year contain African and Creole words such as calalu, a vegetable stew; pone, cornmeal; patu, the Twi word for owl; and tabrabrah, a Coromantee, or Gold Coast, name for a type of rope dance. He heard African animal fables, such as how the crab got its shell, and learned of duppys, or ghosts, and abarra, evil spirits who lured individuals to their death by adopting the guises of friends and relatives. His slaves told him “if you hurt a Carrion Crow in her eyes (or a Yellow Snake) you will never be well until they are well or dead.” He noted that to “drink grave water was the most solemn oath among Negroes” and began to distinguish between different types of African cultural practices. At Christmas, he allowed his slaves to celebrate and watched “Creolian, Congo and Coromantee etc. Musick and dancing.” Six months later, on his departure for Egypt Plantation, a sugar estate of Dorrill’s in Westmoreland, he threw a party for Marina, a house slave and his mistress, at which she got “very drunk.” Thistlewood watched slaves singing and dancing in “Congo” style and marveled at one slave who could eat fire and strike “his naked arm many times with the edge of a bill, very hard, yet receive no harm.”6

The day after Marina’s party, Thistlewood also recorded in his diary, “Pro. Temp. a nocte Sup lect cum Marina,” detailing in schoolboy Latin the last time he slept with his first Jamaican sexual conquest.7 Thistlewood took full advantage of the sexual opportunities offered to white men. Living openly with slave or free mulatto concubines brought no social condemnation. White men were expected to have sex with black women, whether black women wanted sex or not. In his first year in the island—during which he slept with thirteen women on fifty-nine occasions—Thistlewood noted several prurient items of sexual curiosity. On 26 June 1750, he recorded an anecdote from Dorrill about a slave woman with a black lover and a white lover who had twins—one mulatto, one black. Three weeks later, the slave housekeeper at Vineyard borrowed his razor to shave her private parts, leaving Thistlewood to speculate that “some in Jamaica are very sensual.” He learned from slave men how to make a powder that made men irresistible to women and that in Africa girls were not allowed to tickle their ears with a feather because it would arouse them. They also told him that “many a Negro woman [received] a beating from their husbands” when they drank too much cane juice because it made them appear as if they had just had sexual intercourse and that “Negro youths in this Country take unclarified Hoggs lard ... to make their Member larger.”8

Jamaica differed from Thistlewood’s native Lincolnshire in both small and large ways. Thistlewood thought it interesting that “At dinner today, every Body took hold of the Table Cloth, held it up, Threw off the Crumbs and an Empty Plate, Jamaica Fashion.” The heat, sunshine, and sudden tropical downpours were also outside his experience. Nevertheless, by the middle of what passed for a Jamaican winter, Thistlewood found himself “somewhat inur’d to the heat of the Country.” A cold snap found people complaining of “the coldness and Sharpness of the North [wind] and asking one another the things to stand it” even though it was “hotter than our summer in England.” Even more extraordinary was the tropical phenomenon of hurricanes. At midday on 11 September 1751, the wind, already fresh, became a gale. From 3:00 to 7:00 P.M., the hurricane raged. It “Blew the shingles off the Stables and boiling house” of Egypt, “burst open the great house windows that were secured by strong bars,” and inundated the house with water. Trees were blown down everywhere, and the white people fled the great house and “shelter[ed] in the storehouse and hurricane house.” The next day, Thistlewood surveyed the damage: “The boards, staves and shingles blown about as if they were feathers. Most of the new wharf washed away, vast wrecks of sea weeds drove a long way upon the land, a heavy iron roller case carried a long way from where it lay, and half buried in the sand.” Thistlewood was half terrified and half excited about a physical event that made “all the lands look open and bare, and very ragged, [and] the woods appear like our woods in England in the fall of the leaf, when about half down.”9

His fellow whites also piqued his curiosity. One of the first whites Thistlewood met in Westmoreland was “old Mr. Jackson.” Thomas Jackson was hardly a gentleman—he “goes without stockings or shoes, check shirt, coarse Jackett, Oznabrig Trousers, Sorry Hatt, wears his own hair”—yet he was a wealthy man, “worth £8–10,000.” It was not difficult to make money in Jamaica’s booming economy. Thomas Tomlinson, a servant, “expects to make £200–300 per annum by planting 4 to 5 acres on Mr. Dorrill’s land by his leave.” Abundant sexual opportunity, lavish hospitality, excellent shooting and fishing, and a remarkable egalitarianism accompanied whites’ great wealth. Whites were given special legal advantages and were invited as a matter of course to the houses of leading citizens. The custos, or chief magistrate of Westmoreland, Colonel James Barclay, entertained Thistlewood within four months of his becoming an overseer at Egypt. Yet white supremacy was held precariously in a country where over 95 percent of the population on the rural western frontier was black. Whites acted brutally toward blacks because they knew only fierce, arbitrary, and instantaneous violence would keep blacks in check. Thistlewood knew blacks were prepared to turn the tables on their masters should the opportunity arise. On 17 July 1751, Thistlewood “heard a Shell Blown twice ... as an Alarm.” Dorrill—a man experienced in Jamaican mores—was highly agitated because he “greatly feared it was an insurrection of the Negroes, they being ripe for it, almost all over the island.” Dorrill’s agitation was “nought but a Silly Mistake,” but white Jamaicans were correct in assuming that their slaves were “ripe for it.” Two weeks earlier, Old Tom Williams had given “very plain discourse at Table” about the possibilities of a slave uprising (along with ribald tales of how he pleased his slave mistress).10

Africans were always prepared to resist enslavement. A Vineyard slave called Wannica told Thistlewood that in “the ship she was brought over in, it was agreed to rise but they were discovered first. The pickaninies [children] brought the men that were confined, knives, muskets & other weapons.” Thistlewood found himself confronted at every turn by what he perceived as slave villainy. The second day he was at Vineyard, “Scipio’s house was broke into and robb’d as supposed by Robin the runaway Negro.” The robbers were, in fact, Vineyard slaves. Robin came to a bad end: he was hung for repeatedly running away, and his head was put on a pole and “Stuck ... in the home pasture,” where it stayed for four months. Thistlewood responded by whipping delinquents. In his year at Vineyard, he whipped nearly two-thirds of the men and half of the women.11

The Life of Thomas Thistlewood

This book is about how Thomas Thistlewood made sense of the strange environment he found himself in from April 1750 until his death at age sixty-five on 30 November 1786. Thistlewood is our main character, but the book is also about the society he lived in. I want to explore what it meant to be a white immigrant in a land characterized by extreme differences of wealth between the richest and the poorest members.12 I am also interested in examining how Thistlewood operated in one of the most extensive slave societies that ever existed. Our perspective has to be largely that of Thistlewood. The source that we have, despite its remarkable depiction of the lives of illiterate if not inarticulate African-born and Jamaican-born slaves, reflects the prejudices and experiences of a white man in a black person’s country. I make no apologies for the book’s focus on Thistlewood. We need to know more about the foot soldiers of imperialism, especially the men involved at the most intimate level with slaves and slavery in the eighteenth-century British Empire.

Of course, to understand is in some ways to forgive. Forgiveness is especially easy when the person in need of forgiving produces the words that we rely on to construct a historical narrative. This account of Thistlewood’s life and diaries is an empathetic one; it acknowledges the difficulties he was forced to labor under and the different context of an eighteenth-century world with values and experiences removed from our own. I hope, however, that empathy does not tend too much toward sympathy. Sympathy for the travails of a man living in the middle of a war zone (as Jamaica indubitably was in the eighteenth century) is constrained by the realization that the subject was definitely not on the side of the angels. Thistlewood was on the wrong side of history—he was a brutal slave owner, an occasional rapist and torturer, and a believer in the inherent inferiority of Africans.

Thistlewood’s life can be recounted simply. It was not a life full of incident. He was born on 16 March 1721 in Tupholme, Lincolnshire, the second son of Robert Thistlewood, a tenant farmer for Robert Vyner. His father died on 18 December 1727, leaving Thomas £200 sterling to be paid when Thistlewood was twenty-one years old. Thus, from an early age, Thistlewood was in the uneasy position of being a fatherless second son with few prospects of obtaining land. Shortly after his mother’s remarriage to Thomas Calverly on 27 September 1728, Thistlewood was sent to school in Ackworth in York, where he boarded with his stepuncle, Robert Calverly. Thistlewood received a good education for a person of his status, especially in mathematics and science. He continued his schooling until he was eighteen, when he was apprenticed to William Robson, a farmer in Waddingham, eleven miles due north of Lincoln. By this time, he had already established some of the habits he would keep throughout his life. He was interested in books and practical science, and he had begun a regular diary. He kept a diary on a semi-daily basis from 1741 onward.13

He was adrift in the world after his mother died at age forty-two on 7 October 1738. Thistlewood soon realized it was unlikely that he would become a tenant farmer as his father had been and as his brother was to become. He left Robson on 27 July 1740, explaining to him in a letter that he “cannot get money to pay you withal supplying [my] own wants & if I had staid with you till I was of age, I would owe you a great deal.” Other factors played a part in his decision to leave. Thistlewood “had a mind to travell,” and after leaving Robson, he journeyed south to Nottingham, Leicester, Stratford upon Avon, and Bristol. He returned to Robson’s farm after the death of his stepfather on 19 November 1740 but never settled down. By 1743, he had entered into a partnership with his brother to be a tenant farmer for Robert Vyner, but he ended that partnership after less than a year. His wanderlust was strong now, as was his realization that he was unlikely to achieve his ambitions in Lincolnshire, or even England. His determination to leave may have been enhanced by events that occurred in late 1745. On 19 December 1745, Thistlewood was served a warrant for getting Anne Baldock pregnant on 1 August 1745 at a county fair. Baldock miscarried, but Thistlewood’s reputation may have been damaged. On 7 March 1746, he left his family and Tupholme, taking with him £4.71 in ready money. He undertook a two-year journey to India via the Cape of Good Hope and Bahia, Brazil, on a ship belonging to the East India...