eBook - ePub

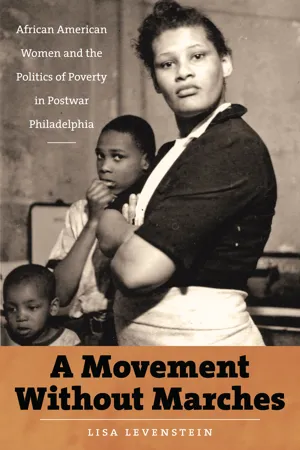

A Movement Without Marches

African American Women and the Politics of Poverty in Postwar Philadelphia

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Movement Without Marches

African American Women and the Politics of Poverty in Postwar Philadelphia

About this book

Lisa Levenstein reframes highly charged debates over the origins of chronic African American poverty and the social policies and political struggles that led to the postwar urban crisis. A Movement Without Marches follows poor black women as they traveled from some of Philadelphia’s most impoverished neighborhoods into its welfare offices, courtrooms, public housing, schools, and hospitals, laying claim to an unprecedented array of government benefits and services. With these resources came new constraints, as public officials frequently responded to women’s efforts by limiting benefits and attempting to control their personal lives. Scathing public narratives about women’s “dependency” and their children’s “illegitimacy” placed African American women and public institutions at the center of the growing opposition to black migration and civil rights in northern U.S. cities. Countering stereotypes that have long plagued public debate, Levenstein offers a new paradigm for understanding postwar U.S. history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Movement Without Marches by Lisa Levenstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

“Tired of Being Seconds” on ADC

In 1962, Ada Morris walked out of her run-down apartment in search of an unoccupied pay phone where she could place a call to her welfare caseworker. She did not own a phone because the welfare department considered it a “luxury,” and she could not afford to buy one anyway. When Mrs. Morris got through to her caseworker, she informed him of the urgency of her situation: “I don’t call up very often and complain about my finances to you people, but I would like some sort of assistance.” Mrs. Morris explained that her husband had defaulted on several child support payments and she was sinking into debt. Her most recent welfare check was “only $47.80, which I entirely owed the whole check to the rent man.” She had defaulted on her $65.00 rent to “pay the food bill, which was $42.00 for two weeks for six people, which I think is very good, don’t you?” Mrs. Morris’s caseworker agreed that her $42.00 food bill demonstrated remarkable thrift. However, he told her that he could not provide her with supplementary income until the “halfway mark” of the month. With not a penny to her name and her debts piling up, Mrs. Morris had exhausted all options and had nowhere else to turn for assistance. “When people say ‘Oh, you’re on relief’ [welfare], they think the average person that’s on relief is sitting down with nothing to do,” she told researchers in the early 1960s. “Being on relief is a . . . strain, whether anybody knows it or not. Physically, mentally—a strain.”1

Women like Mrs. Morris endured the “strain” of welfare because it was an improvement over their previous living arrangements. Most of them had at one time supported themselves and their children through employment, but health problems, lack of child care, or layoffs had prevented them from keeping their jobs. Since their relatives, friends, and neighbors were also poor, mutual support networks could not solve their problems. Most women viewed depending on men for survival as an impossible or unattractive solution, given their past experiences with nonsupport, infidelity, and abuse. Raising children in poverty was laborious and stressful, and the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) program provided only minimal financial support for women’s efforts. Yet by the early 1960s, testament to the extent of poverty among African Americans in Philadelphia, over one-tenth of the city’s African American population and one-quarter of its African American children were receiving ADC. Since each year 40 percent of recipients left the program and were replaced by others, the number of people who received assistance from the ADC program at some point in their lives was even higher than these percentages would indicate.2

Working-class African American women and welfare authorities held fundamentally incompatible understandings of the ADC program. Women focused on expanding and capitalizing on the opportunities the program provided. They believed ADC should help them live autonomously, pay their bills on time, rent clean and safe apartments, obtain health care when needed, and purchase adequate food and clothing for their families. State and local welfare authorities focused their efforts on containing the program’s expenditures by preventing fraud and keeping costs low. They enforced policies that made life on ADC as unattractive as possible in order to ensure that only the neediest women would seek assistance. Women had to deplete all their savings and assets to qualify for ADC, and the program’s restrictions on securing additional resources prevented them from rising above a subsistence level of living. Prohibitions against living with men placed roadblocks in women’s efforts to cultivate intimate relationships.

Women sought dignity and autonomy by challenging the constraints the welfare department placed on their lives. Most believed any job was preferable to welfare, but some refused to give up ADC for low-wage employment they deemed exploitative. Some viewed domestic work as particularly demeaning and saw little benefit in leaving ADC for jobs that yielded comparable or even lower income. Others insisted on obtaining more money than either welfare or low-wage jobs provided and earned income secretly, “under the table,” while receiving ADC. Relationships with men also became points of contention. Welfare policies prohibited women from living with men because state authorities assumed the men would, or should, provide women with financial support. They believed women who lived with men should give up welfare and get married. Many women refused to sacrifice the steady income they received from ADC to marry men whom they considered unreliable. They had steady boyfriends while receiving welfare, relying on ADC to provide them with more leverage in their relationships.3

In the years after World War II, in Philadelphia and cities across the nation, African American women’s pursuit of ADC inspired fierce public opposition. In a climate of white resistance to civil rights, several outspoken Democratic legal authorities in Philadelphia began to advocate restricting women’s access to ADC, charging that welfare programs took money from upstanding “taxpayers” to support mothers who had “illegitimate” children and depended on public assistance as a “way of life.” Over the course of the 1950s, their harsh criticism was echoed by many ordinary whites and African Americans who exhibited both disdain for ADC recipients and resentment of their allegedly “easy lives.” Even prominent civil rights activists tempered their support of ADC, expressing in their reservations the gender- and class-based limitations of their visions of social justice. When liberal advocacy groups and state and local welfare authorities tried to defend the program, they failed to challenge many of the assumptions that lay at the core of the anti-welfare discourse. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, although women managed to retain and even expand their foothold in the ADC program, they faced increasingly strident public resistance.

The burgeoning opposition to African American women’s use of welfare inspired a significant body of academic scholarship documenting the lives of Philadelphia’s ADC recipients. The most extensive work was compiled and directed by Jane C. Kronick, a professor of social work at Bryn Mawr College who received her Ph.D. from Yale University. Between 1959 and 1962, Kronick conducted a study of a random sample of 239 Philadelphia ADC recipients. She analyzed their casework files and hired two African American women to conduct interviews with 119 of the women. Kronick wrote several reports exploring her findings, and many social work graduate students at Bryn Mawr based their Masters’ theses on the information she compiled. In their work, Kronick and these students critically interrogated the negative images of African American “illegitimacy” and the “culture of poverty” found in white newspapers and academic discourse by exploring ADC recipients’ employment histories, personal relationships, material circumstances, and survival strategies. The mothers who participated in the study were also well aware of the demeaning images of welfare recipients that were circulating in the press. Many of them tried to show the interviewers that their lives did not conform to popular stereotypes by emphasizing their commitment to their children. Yet they also described how the stigma of ADC and the severe poverty they confronted prevented them from properly fulfilling their familial obligations. Several of the studies include excerpts from the interview transcripts that allow us to hear and interpret these women’s own words. Read critically, and in conjunction with other primary sources, the studies provide us with rare insight into ADC recipients’ past struggles and daily lives. (For more information on the Bryn Mawr studies and other first-person accounts in this book, see the Appendix.)

The Racialization of Welfare

In 1935, when the federal government created the ADC program as part of the Social Security Act, no one predicted that it would become the largest welfare program in the nation or that African American women would become major beneficiaries of the grants. The women social reformers who drew up the blueprint for ADC modeled the program on state Mothers’ Assistance grants, which were instituted in the early twentieth century primarily to serve small numbers of white and immigrant widows.4 Gendered and racialized ideas about poverty undergirded the sharp stratifications in the welfare programs created by the Social Security Act. Old-age pensions and unemployment insurance disproportionately benefited whites and men with stable employment histories. State authorities portrayed these benefits as based directly on recipients’ past earnings or “right” to assistance, even though the proportion of workers’ wages they provided was calculated according to a sliding scale that benefited those who earned lower incomes. The ADC program, by contrast, served single mothers who, instead of receiving benefits as a “right,” had to pass strict means and morals tests to receive meager grants accompanied by state supervision.5

In 1937, Pennsylvania changed the name of Mothers’ Assistance to Aid to Dependent Children, and African American women quickly became the primary clients of Philadelphia’s program. The Pennsylvania legislature provided two-thirds of the funding for ADC, and the rest came from the federal government, which imposed very few requirements on state authorities. The Philadelphia Department of Public Assistance (DPA) administered ADC, but state-level authorities made all of the important policy decisions.6 In Philadelphia, many of the first African American women who received ADC entered the welfare system in the 1930s through the state’s General Assistance (GA) program, which provided grants to needy persons regardless of their marital status. Since Pennsylvania welfare authorities conserved funds by moving women off GA and onto the new federal program, they increasingly opened ADC to unmarried, separated, and deserted women, many of whom were African American.7As early as 1940, African Americans comprised 13 percent of Philadelphia’s population, but 62 percent of its ADC recipients. Throughout the postwar period, whites comprised the majority of ADC recipients on the national level, but in northern cities such as Philadelphia, black women maintained a strong presence in the program.8 By the early 1960s, when Philadelphia administered ADC grants to more than 65,000 single mothers and children, African Americans comprised at least 85 percent of the recipients.9

Many public officials linked the large numbers of African Americans who relied on welfare with black migration, suggesting either that welfare benefits attracted new migrants or, slightly more sympathetically, that migration caused black poverty. Neither position accounted for African Americans’ strong presence in welfare programs. African Americans migrated to Philadelphia in search of employment, not welfare benefits.10 They frequently faced difficulties finding jobs not because they were born in the South but because of their relatively low educational levels, racial discrimination, and the diminishing numbers of entry-level jobs in the city. Many longtime black residents faced similar problems.11 In 1960, 65 percent of ADC recipients were born outside Philadelphia, a figure to be expected in a city that was a frequent destination for southern migrants. However, most of them had lived in the city for more than five years. The one-year residency requirement meant that those who had recently moved to Philadelphia could not receive ADC benefits even if they tried to apply.12 In the early 1960s, when Rhode Island and New York State eliminated residency requirements, newcomers did not suddenly flock to welfare offices in search of assistance, despite public anxiety that the policy shift might attract large numbers of new applicants.13

Southern origins did give many African Americans a unique perspective on welfare policies. From its inception, racial discrimination has permeated the U.S. welfare state. Working-class African Americans were largely shut out of the most generous and publicly respected programs such as old-age pensions, and in the South, many African American women with children could not even gain access to ADC, especially during seasonal labor shortages when white landlords needed cotton pickers. In the postwar period, several states enacted strict restrictions on ADC ranging from “suitable home” laws to employment requirements that especially targeted blacks.14 As a result, many African Americans in Philadelphia did not take the availability of ADC for granted. They appreciated the availability of welfare and viewed it as an essential safety net for struggling families.

Black women received ADC benefits far more frequently than white women because of their disproportionate poverty and the DPA’s insistence that only the poorest of the poor should receive assistance. In 1960, 46 percent of Philadelphia’s African American households lived in poverty, with annual incomes under $4,000, compared to 20 percent of white households. Since the poor white households frequently consisted of older persons living either alone or in couples, while the poor black households often consisted of younger and larger families with children, poverty was even more widespread among African Americans than household-based statistics suggest.15 The DPA took out liens on welfare recipients’ homes and placed strict limits on the value of their savings, life insurance, and cars. These policies discouraged and disqualified more whites than African Americans from receiving public assistance because whites were more likely to have such assets.16 Similarly, because more whites than African Americans had relatives who could support them, whites were disproportionately disqualified by policies forcing applicants to obtain financi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- A Movement Without Marches

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations, Tables, and Maps

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER ONE “Tired of Being Seconds” on ADC

- CHAPTER TWO Hard Choices at 1801 Vine

- CHAPTER THREE Housing, Not a Home

- CHAPTER FOUR “Massive Resistance” in the Public Schools

- CHAPTER FIVE A Hospital of Their Own

- CONCLUSION

- Appendix: Note on First-Person Sources

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index