- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Ozark region, located in northern Arkansas and southern Missouri, has long been the domain of the folklorist and the travel writer — a circumstance that has helped shroud its history in stereotype and misunderstanding. With Hill Folks, Brooks Blevins offers the first in-depth historical treatment of the Arkansas Ozarks. He traces the region’s history from the early nineteenth century through the end of the twentieth century and, in the process, examines the creation and perpetuation of conflicting images of the area, mostly by non-Ozarkers.

Covering a wide range of Ozark social life, Blevins examines the development of agriculture, the rise and fall of extractive industries, the settlement of the countryside and the decline of rural communities, in- and out-migration, and the emergence of the tourist industry in the region. His richly textured account demonstrates that the Arkansas Ozark region has never been as monolithic or homogenous as its chroniclers have suggested. From the earliest days of white settlement, Blevins says, distinct subregions within the area have followed their own unique patterns of historical and socioeconomic development. Hill Folks sketches a portrait of a place far more nuanced than the timeless arcadia pictured on travel brochures or the backward and deliberately unprogressive region depicted in stereotype.

Covering a wide range of Ozark social life, Blevins examines the development of agriculture, the rise and fall of extractive industries, the settlement of the countryside and the decline of rural communities, in- and out-migration, and the emergence of the tourist industry in the region. His richly textured account demonstrates that the Arkansas Ozark region has never been as monolithic or homogenous as its chroniclers have suggested. From the earliest days of white settlement, Blevins says, distinct subregions within the area have followed their own unique patterns of historical and socioeconomic development. Hill Folks sketches a portrait of a place far more nuanced than the timeless arcadia pictured on travel brochures or the backward and deliberately unprogressive region depicted in stereotype.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hill Folks by Brooks Blevins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Beginnings

IN THE HISTORY of the Ozark region of Arkansas, the nineteenth century is more than an arbitrary succession of decades and years extracted from human experience. The century instead quite neatly encapsulates an era dominated by the settlement of a frontier and the development of a society. In 1800 the Ozark region was home to no white settlers and served as little more than a seasonal hunting ground for the Osage, whose more permanent dwellings lay many miles to the north. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Arkansas Ozarks was home to approximately a quarter of a million American settlers; the region had been fully settled and had reached the capacity of people the land could support.

Although most of the Ozark region remained quite rural and even isolated by American standards in 1900, the forces of modernization synonymous with the nineteenth century had not eluded Ozarkers. By mid-century, steamboats plied the swift waters of the White River above Batesville, penetrating the rugged hills and exposing to the outside world the narrow bottoms of small settlements and small farms. In the decades following the Civil War, large numbers of Ozark farmers entered the staple-crop economy, and general stores sprang up in small towns and at rural crossroads to serve a burgeoning population. In the 1880s railroads skirted the region, bringing prosperity or at least opportunity to a limited number of Ozark residents and revealing a taste of things to come in the early twentieth century.

The three chapters that follow explore developments in the region from the beginnings of white settlement around the time of the War of 1812 to the end of the century. Chapter 1 establishes the geographical diversity of the Arkansas Ozarks, traces the waves of pre-Civil War settlement, and charts the agricultural development of a yeoman-dominated society. Chapter 2 carries the discussion of farming in the region to the end of the nineteenth century, revealing an increasingly diverse agricultural economy of cotton growers, orchardists, general farmers, and isolated semisubsistence farmers. Chapter 3 explores social life—education, family life, religion, and community and social activity—in the region during the first century of white settlement.

1

The Other Southern Highlands

IN EARLY NOVEMBER 1818 a twenty-five-year-old New Yorker and his companion set out on a three-month journey through a rugged, sparsely settled land west of the Mississippi known as the Ozarks. Leaving Potosi, a small Missouri outpost some sixty miles southwest of St. Louis, the duo traveled hundreds of miles on foot and by horseback through a wild frontier in which they found bear, deer, elk, buffalo, the remnants of Osage hunting camps, and the freshly built cabins of white settlers. They found a country diverse beyond their expectations—a land of sterile hills and fertile prairies, of wooded valleys and treeless balds, of great virgin forests and rivers so clear no fish could escape the canoeists’ gaze.

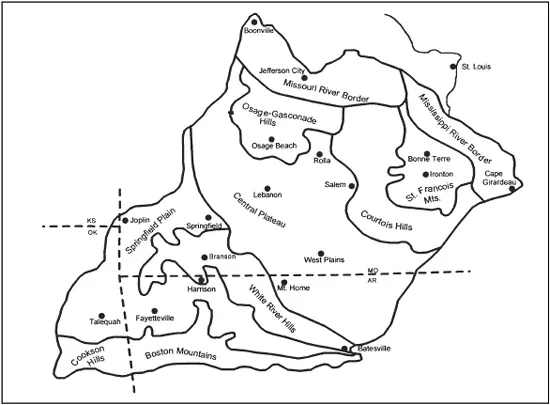

The young New Yorker was Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, a mineralogist who would later build a reputation as an expert on Native American customs and affairs in the Old Northwest. Schoolcraft’s journal, published in London two years after his journey, reveals his acute awareness of topographical and geological variations within the region, foreshadowing variations of Ozark development based on subregional characteristics. The Arkansas Ozarks can be broadly divided into four geographic subregions: the Salem Plateau, White River Hills, Springfield Plain, and Boston Mountains. Approaching the area from the northeast, Schoolcraft and his companion Levi Pettibone first entered the Salem, or Central, Plateau, a wide swath of gently undulating upland stretching from the southeastern border of the Ozarks through southern and central Missouri to the region’s northeastern edge. Composed of generally infertile, rocky soils, the Salem Plateau comprises only the northeastern corner of the Arkansas Ozarks, or the upland counties east of the White River.

Schoolcraft, having been raised in the prosperous Hudson Valley, found nothing to recommend the Salem Plateau to prospective settlers. He discovered a “sterile soil, destitute of wood, with gentle elevations, but no hills or cliffs, and no water.” After one difficult hike through the wilderness east of the Great North Fork (North Fork) of the White River, Schoolcraft sighed in his journal: “Nothing can exceed the roughness and sterility of the country we have today traversed.” The young travelers found bluffs lined with pine, rocky hillsides, and forests of post oak and gnarled black oak, not the coveted majestic white oak found farther west. The subregion’s relative barrenness was represented most conspicuously by cedar glades, outcroppings of exposed bedrock fit only for the growth of cedars and greenbriers. Despite its manageable terrain and tempting location at the southeastern edge of the region, settlers would avoid the rocky, infertile interior of the Salem Plateau for decades, choosing instead to settle the fertile plains of the western Ozarks and the river bottoms of the east.1

“The country passed over yesterday, after leaving the valley of the White River, presented a character of unvaried sterility, consisting of a succession of lime-stone ridges, skirted with a feeble growth of oaks, with no depth of soil, often bare rocks upon the surface, and covered with coarse wild grass.” Such was Schoolcraft’s observation after having traversed the White River Hills, a steep and rugged range that follows the White River on its circuitous route from northwestern Arkansas up into Missouri and back down through north central Arkansas almost as far as Batesville. Extending sometimes for fifteen or twenty miles on either side of the river, these hills present the traveler or settler with as daunting a sight as is found in the Ozarks.2

Nestled within their protective embrace is the White River, the life-blood of the Ozark region and the destination of northern Arkansas’s streams and branches. Schoolcraft marveled as he floated along the clear river: “Every pebble, rock, fish, or floating body, either animate or inanimate, which occupies the bottom of the stream, is seen while passing over it with the most perfect accuracy; and our canoe often seemed as if suspended in the air, such is the remarkable transparency of the water.” The valley of the White River had attracted the first white settlers to the Arkansas Ozarks a few years before Schoolcraft’s arrival, though it continued to serve as a prime spring and fall hunting ground for the Osage. The White River would connect large sections of the interior Ozarks with the outside world until the early twentieth century, when the railroad replaced the steamboat as exporter of cotton and hides and purveyor of manufactured goods from such places as New Orleans and St. Louis. But the White River Hills also separated the inhabitants of the interior plateaus from the river valley and denied them access to river trade, thus isolating pioneers for many years in the vast open lands beyond these protective hills.3

To the west and northwest of the White River Hills lies a fertile, gently sloping prairie, the Springfield Plain. Blessed with the richest soils of the Ozarks, the Springfield Plain occupies a meandering corridor between the White River Hills and the Boston Mountains, extending from Bates-ville in the east to the border of the Great Plains in the west. The Springfield Plain impressed the discriminating Schoolcraft. Having escaped the inhospitable White River Hills, he and Pettibone discovered the plain’s “prairies, which . . . are the most extensive, rich, and beautiful, of any which I have seen west of the Mississippi River. They are covered by a coarse wild grass, which attains so great a height that it completely hides a man on horseback in riding through it.”4

Thousands of pioneers shared Schoolcraft’s estimation of the Springfield Plain. By the time Arkansas achieved statehood almost two decades later, in 1836, the fertile prairies would rank among the most populous and prosperous areas of the state. Just as the Salem Plateau’s thin soils and rocky hills hindered settlement and agricultural production, the Springfield Plain’s fertility invited immigrants and rewarded their labors. The development of both areas would depend heavily on their differing topographies and soil qualities.

Schoolcraft and Pettibone avoided the Ozarks’ highest and most rugged elevations, as would at least a generation of settlers. The Boston Mountains make up the entire southern boundary of the Ozark region, extending from eastern Oklahoma to the escarpment south of Batesville. Though the subregion is generally characterized by relatively smooth wooded slopes that rise up to 1,200 feet above the valley floor, the Boston Mountains area is home to a few lowland basins, such as the Richwoods of present-day Stone County, that attracted early pioneers into the isolated upland ranges. The mountains’ most prized resource was timber, especially the mammoth white oaks that canopied the western and southern slopes of ridges. These stands of virgin timber would eventually attract lumber companies and influence the routing of railroads into some of the region’s most remote mountain coves and hollows.5

When Schoolcraft arrived in the Arkansas Ozarks, most of the settlers he encountered had been there only a short time, and many lived isolated lives miles from another human. These settlers harbored the white pioneer’s fear and resentment of the Native American, in this case mainly the Cherokee, to whom an 1817 treaty had granted thousands of acres lying south and west of the White River. Even the Cherokee were newcomers. The Ozark region had historically been the domain of the Osage, who seasonally swept down into the White River country from their villages in western Missouri to hunt buffalo and deer, leaving in their wake abandoned camps of “inverted bird’s nest” huts made of flexible green poles (perhaps the saplings of the Osage orange or hedge apple tree, known in the Ozarks as bois d’arc or “bodark”). In 1808 the Osage had given up their lands between the Missouri and Arkansas Rivers east of a line drawn due south from Fort Osage, on the Missouri about twenty miles east of the present site of Kansas City, to the Arkansas. Even before the Osage signed away the region, the Cherokee, along with smaller numbers of Delaware and Shawnee, had begun to settle the Ozarks. The Cherokee would retain title until 1828, when they exchanged their Arkansas lands for 7 million acres in the Indian Territory (Oklahoma).6

MAP 1.1. Geographic Regions of the Ozarks. From Milton D. Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2001).

The earliest white settlers of the Arkansas Ozarks entered the region from the southeast by way of the White River. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, a middle-aged Ulster Irishman left his home in Tennessee and settled his family in a log cabin on a rise above the west bank of the White River in what today is Stone County. John Lafferty, the first recorded white settler in the Arkansas Ozarks, was a veteran of the American Revolution and a professional keelboat operator who had explored the upper White River country as early as 1802. In late 1810 Lafferty and his son-in-law Charles Kelly permanently relocated their families in the wilderness, which was teeming with bear, deer, and panthers. Shortly after Lafferty’s arrival, Dan Wilson and his three sons settled at the mouth of Rocky Bayou (Izard County), farther up the river. Within a few years other settlers made their way up Rocky Bayou and other tributaries, prompting Poke Bayou merchant Robert Bean to ascend the river by keel-boat with salt, whiskey, powder, and lead to exchange for buffalo hides, bear skins, and chickens.7

Poke Bayou, settled in 1812 by Missourian John Reed, quickly became the region’s largest settlement and trading center. Today known as Bates-ville, Poke Bayou lay some thirty miles downstream from Lafferty’s place, and its position at the fall line just a few miles above the Ozark escarpment assured its continued prominence. Poke Bayou became the center of operations for the upper White’s busiest keelboatman before 1819. John Luttig, an agent for St. Louis merchant Christian Wilt, bartered for pelts, hides, tallow, buffalo tongues, beef, turkeys, ham, and venison by supplying the frontiersmen whiskey, silk, corn, and other goods. He also carried on a brisk trade with the various resettled Native American groups living west and south of the river. By the early 1820s, the combined population of Weas, Peorias, Kickapoos, Shawnee, and Pianka-shaws numbered approximately 10,000. In January 1819 Schoolcraft encountered Lafferty’s widow, who, like the other white settlers on the right bank of the river, was anxious over the recent treaty ceding her lands to the Cherokee. By the time of Schoolcraft’s visit, the widow Lafferty still lived an isolated existence, but the village of Poke Bayou had grown to a dozen houses, including Robert Bean’s permanent trading post.8

In 1815 North Carolinian Jehoida Jeffery left southern Illinois with a large stock of cattle and horses and settled the following year upriver from Rocky Bayou, two miles above what would become the Mount Olive community. Jeffery, with whom Schoolcraft and his partner spent a January night, would soon become prominent in local politics, once enough people entered the hills to make the effort worthwhile. As a member of the territorial legislature in 1824, he would prove influential in the creation of a new county, Izard, which he would serve as judge for more than a decade.9

Another immigrant with political aspirations settled about twenty-five miles above Mount Olive at the mouth of the North Fork of the White River. Jacob Wolf, a Kentuckian of German ancestry born in western North Carolina, joined members of his extended family there around 1820. When Schoolcraft had visited the area in 1819, he found only a man named Matney who operated a small trading post a half-mile above the mouth of the North Fork. In 1824 Wolf purchased a plot of land just below this junction, on the heights overlooking the White River, and later constructed a large, two-story dog-trot house of hewn pine logs. The house, which served at times as a trading post, inn, and post office, became the seat of justice for Jeffery’s new Izard County. Wolf’s brother-in-law, John Adams, became Izard’s first county judge, and four years later a neighbor, Matthew Adams, was elected sheriff. Wolf gained appointment as Izard County’s representative to the territorial council (upper house) in 1827, a seat that he would retain until Arkansas’s statehood in 1836; he would later serve as postmaster of North Fork (Norfork) from 1844 until his death in 1863.10

On his journey up the White River, Schoolcraft encountered two families at the mouth of Beaver Creek in present-day Taney County, Missouri. The Holt and Fisher families had located there only months earlier and represented the farthest advance of white settlement up the valley by the end of 1818. The previous year’s advance had been marked by the extended settlement of the Coker family. Joe Coker and his Native American wife Ainey left Alabama for the White River valley in 1814, settling on the Sugar Loaf Prairie of Boone County. In January 1815 Joe’s father Buck settled in a bend of the river near his son. By December 1818 a total of four families lived along an eight-mile stretch of the river in the vicinity of Sugar Loaf Prairie.11

Following the tributaries of the White River, settlers eventually pushed into the Ozarks’ most remote Boston Mountain valleys and hollows. In the early 1820s Kentuckian Robert Adams ventured up the Buffalo River and settled on Bear Creek. In 1825 Tennesseans John Brisco and Solomon Cecil settled even farther up the valley near the present-day Newton County communities of Jasper and Compton, respectively.12

The southern section of the Boston Mountains was settled by pioneers who came up tributaries of the White and Arkansas Rivers and by others who traveled by land across the Ozark wilderness. In 1811, after the New Madrid earthquake had decimated their fortunes, John Benedict, a young New Yorker, and his three brothers-in-law traveled by land from southeastern Missouri into the Arkansas backwoods, where they settled on the Little Red River in what is now Cleburne County. Subsisting on the plentiful game of the area, the four young men cleared thirty acres and built three small cabins. Two and a half years later Benedict’s father-in-law John Standlee brought his family, slaves, and livestock to join them. The last of the Standlees left the area in 1821, and a few years later John Lindsey Lafferty, son of the original Ozark pioneer, purchased part of the Standlee land. Lafferty, like Jehoida Jeffery and Jacob Wolf before him, parlayed his pioneer status into political power, helping to organize the new county of Van Buren in 1833 and serving intermittently as county judge and state legislator over the following thirty years.13

The Black River and its tributaries, the Strawberry and the Spring Rivers, deposited settlers along the eastern rim of the Ozarks. On his return trip to Potosi in early 1819, Schoolcraft passed through a “country wear[ing] a look of agriculture, industry and increasing population” in the environs northeast of Poke Bayou. The traveler covered more than thirty miles along the eastern rim of the Salem Plateau before encountering a village of fifteen buildings—including a gristmill, whiskey distillery, blacksmith shop, and tavern—on a tributary of the Strawberry River. To the northeast, on a height overlooking the confluence of the Black and Spring Rivers, lay Davidsonville, site of Arkansas’s first post office and the original seat of justice for Lawrence County (which covered almost the entire Ozark section of Arkansas at one time).14

While explorers and settlers infiltrated the eastern Ozarks in the early nineteenth century, the majority of northwestern Arkansas lands remained in the possession of the Cherokee until 1828. Consequently, the area was legally off-limits to white settlers for almost two decades after settlement began on the White River, but some white families did make their way into the region before 1828. One history of Washington County reports that six white families settled there as early as 1826 and had their corn crops decimated by soldiers’ swords for their trespassing. With the signing of the 1828 treaty removing the Cherokee westward beyond the Arkansas border, the floodgates were opened. Especially appealing to settlers were the rolling prairie lands of Washington and Benton Counties.15

Many of the area’s first settlers moved up from the Arkansas River valley. William McGarrah’s story illustrates the circuitous route several of these pioneers followed to northwestern Arkansas. Born in South Carolina in the 1790s, McGarrah made a brief sojourn in Tennessee before...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Hill Folks

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS MAPS, AND TABLE

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- PART ONE Beginnings

- PART TWO Transitions and Discoveries

- PART THREE Endings and Traditions

- CONCLUSION

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX