eBook - ePub

The Louis A. Pérez Jr. Cuba Trilogy, Omnibus E-book

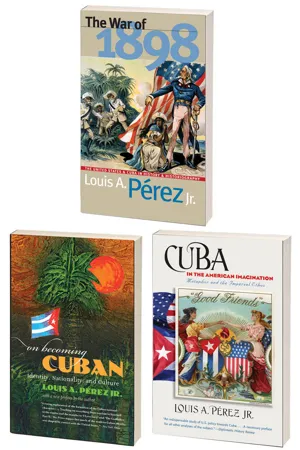

Includes The War of 1898, On Becoming Cuban, and Cuba in the American Imagination

- 1,152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Louis A. Pérez Jr. Cuba Trilogy, Omnibus E-book

Includes The War of 1898, On Becoming Cuban, and Cuba in the American Imagination

About this book

Louis A. Pérez Jr. is one of the most influential historians of Cuba. Available for the first time as an Omnibus Ebook edition, this three-volume set brings together three of Pérez’s most acclaimed works on Cuba and its relations to the United States.

This Omnibus Ebook contains:

The War of 1898 presents both a critique of the conventional historiography and an alternate history of the war that is informed by Cuban sources.

On Becoming Cuban explores the rich cultural ties between Cuba and the United States and reveals their startling influence on the way Cubans see themselves as a people and as a nation.

Cuba in the American Imagination describes how for more than two hundred often turbulent years, Americans have imagined and described Cuba and its relationship to the United States by conjuring up a variety of striking images — Cuba as a woman, a neighbor, a ripe fruit, a child learning to ride a bicycle. Pérez Jr. offers a revealing history of these metaphorical and depictive motifs and discovers the powerful motives behind such characterizations of the island.

This Omnibus Ebook contains:

The War of 1898 presents both a critique of the conventional historiography and an alternate history of the war that is informed by Cuban sources.

On Becoming Cuban explores the rich cultural ties between Cuba and the United States and reveals their startling influence on the way Cubans see themselves as a people and as a nation.

Cuba in the American Imagination describes how for more than two hundred often turbulent years, Americans have imagined and described Cuba and its relationship to the United States by conjuring up a variety of striking images — Cuba as a woman, a neighbor, a ripe fruit, a child learning to ride a bicycle. Pérez Jr. offers a revealing history of these metaphorical and depictive motifs and discovers the powerful motives behind such characterizations of the island.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Louis A. Pérez Jr. Cuba Trilogy, Omnibus E-book by Louis A. Pérez Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

On Becoming Cuban

Identity, Nationality, Amd Culture

The University of North Carolina Press

Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill

This book was published with the assistance of the H. Eugene and Lillian Youngs Lehman Fund of the University of North Carolina Press. A complete list of books published in the Lehman Series appears at the end of the book.

© 1999 The University of North Carolina Press

Preface to the Paperback Edition © 2008 The University

of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Minion and Eagle types by Keystone Typesetting, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence

and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for

Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Preface to the Paperback Edition © 2008 The University

of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Minion and Eagle types by Keystone Typesetting, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence

and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for

Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the original edition

of this book as follows:

Pérez, Louis A., 1943-

On becoming Cuban: identity, nationality, and culture /

by Louis A. Pérez Jr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Cuba—Civilization — American influences. 2. Nationalism—

Cuba—History. 3. Cuba—Relations — United States. 4. United

States — Relations — Cuba. I. Title

F1760.P47 1999

972.91 — dc21 98-42664

CIP

of this book as follows:

Pérez, Louis A., 1943-

On becoming Cuban: identity, nationality, and culture /

by Louis A. Pérez Jr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Cuba—Civilization — American influences. 2. Nationalism—

Cuba—History. 3. Cuba—Relations — United States. 4. United

States — Relations — Cuba. I. Title

F1760.P47 1999

972.91 — dc21 98-42664

CIP

ISBN 978-0-8078-5899-8

12 11 10 09 08 5 4 3 2 1

For DMW

Contents

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Acknowledgments

Introduction

CHAPTER 1. Binding Familiarities

Sources of the Beginning

Defining Differences

Meanings in Transition

Toward Definition

Affirmation of Affinity

Nationality in Formation

CHAPTER 2. Persistence of Patterns

The Long War

Design without a Plan

The Order of the New

Terms of Adaptation

CHAPTER 3. Image of Identity

Travel as Transformation

Representation of Rhythm

CHAPTER 4. Points of Contact, Sources of Conflict

The Meaning of the Mill

The Presence of the Naval Station

The Evangelical Mission

Baseball and Becoming

CHAPTER 5. Sources of Possession

Between Image and Imagining

The Promise of Possibilities

Configurations of Nationality

CHAPTER 6. Assembling Alternatives

In Pursuit of Purpose

Between Arrangement and Arrival

Miami Meditations

CHAPTER 7. Illusive Expectations

The Reality of Experience

Lengthening Shadows

Revolution

Appendix: Tables

Notes

Index

Illustrations

Cuban émigré neighborhood, Ybor City, Tampa, ca. 1890s 29

Liceo Cubano, Ybor City, Tampa 30

Sánchez and Haya Cigar Factory, Tampa, 1898 31

Martínez Ybor Cigar Factory, Tampa, ca. early 1890s 32

Hotel de La Habana, Ybor City, Tampa, 1889 40

Valdés Brothers General Store, Tampa, 1897 41

José Martí with Cuban cigar workers, Ybor City, Tampa, 1892 47

José Martí with local organizers of the PRC, Key West, 1893 48

Cigarette advertisement from El Sport, November 1886 77

Bullfight ring, Santiago de Cuba, 1898 79

Ruins of Victoria de las Tunas, 1900 100

Advertisement for La Gloria City agricultural colony, Camagüey province 112

Residence of Mr. and Mrs. W. E. Schultz, Santa Fe, Isle of Pines, 1901 114

Residence of T. M. Symes II, Santa Fe, Isle of Pines, 1901 115

Members of the Hibiscus Club, Isle of Pines, 1901 116

Hotel Plaza, Ceballos agricultural colony, Camagüey province 117

Reconstruction in Santiago de Cuba, 1901 118

Construction of Contramaestre Bridge over Cauto River, 1902 120

Lonja de Comercio, Havana 121

Camagüey Railroad Station, ca. 1910s 123

San Rafael Street, Havana, 1901 128

Los Estados Unidos General Store, Antilla, ca. 1905 131

Central Railway Station, Old Havana, 1912 135

Raising of the Cuban flag, May 20, 1902 142

Hotel Manhattan, Havana, 1919 171

Tourist postcard, ca. 1920 172

Sloppy Joe’s Bar, Havana 173

Hotel Almendares, Marianao, ca. 1920s 174

Oriental Park Race Track, Marianao 175

Golf course, el Country Club, Havana, ca. 1920s 176

Jack Johnson-Jess Willard fight, 1915 177

Kid Chocolate (Eligio Sardinas) 178

Kid Gavilán (Gerardo González) 180

Nocaut sports magazine, early 1930s 182

Gran Casino Nacional, Marianao, ca. early 1930s 183

Sheet music covers, ca. 1910s-1920s 184

Havana nightlife by day 195

Tropicana Casino, Havana 197

Professional rumba stage dancers, Havana, ca. early 1930s 200

Sheet music cover of Perry Como “mambo” hit, 1954 209

Home of Jatibonico sugar mill administrator, Camagüey province, ca. 1920 223

Preston batey of United Fruit Company 225

Delicias residential zone, ca. 1920s 227

U.S. servicemen arriving at Caimanera, ca. 1940s 241

Baptist church, Cabaiguán 244

Presbyterian church, Havana 245

Quaker schoolhouse, Banes, 1925 246

Quaker Sunday school class, Gibara, 1910 248

Camilo Pascual 262

Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso 263

Pedro “Pete” Ramos 264

Edmundo “Sandy” Amorós 265

Team portrait of Habana Baseball Club, 1911 268

Ford advertisement in La Mujer Moderna, March 1926 318

One-cylinder Oldsmobile, 1901 337

Street scene, Caimanera, ca. 1950s 352

Advertisement for U.S. correspondence school in Bohemia, 1958 362

Capitolio, a replication of the U.S. Capitol 375

Gibara Yacht Club, Oriente, ca. 1930s 376

Tip Top Baking Co. cake advertisement 378

Methodist Candler College, Havana 403

Advertisement for school placement service of Continental Schools, Inc., Havana 407

Advertisement for “modern” furniture, 1957 475

Miami storefront, “Cuba in Miami” 502

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Change recurs with such frequency in Cuba that it assumes the appearance of a changeless condition. Not exactly like history repeating itself, but rather what writer Antonio Benítez Rojo alluded to when he imagined Cuba as “the island that repeats itself,” a place in which “every repetition is a practice that necessarily entails a difference.” The novelty of change was normal. But the changes that repeated themselves were necessarily different, if only because the historical circumstances of change were different.

The pattern of recurring change originated early in the nineteenth century, in the very sources by which Cubans arrived at a shared sense of nationality and collective idea of nation. The pages that follow examine the ways that change was induced: by way of production strategies and market forces, through the transfer of technology and knowledge, as a result of the migration of people and the movement of ideas. The changes were interrelated, and most were related to sugar. All through the nineteenth century the increase of sugar production, the expansion of trade relations, the formation of new social classes, the growth of population—especially among people of color, free and enslaved—combined to shape a distinctive political economy in which the logic of nation took form. Cultural systems evolved as a function of changing material circumstances and shifting moral imperatives, and inevitably served as the context in the which the sensibility of nationality took shape. Culture played a central role in the process by which change was normalized, to enable and enact transition, which suggests too that culture was the means by which change was registered and ratified.

Change begot change: new economic forms, new political possibilities, new social relationships, and inevitably new tensions and new contradictions. And more change followed: revolution and insurrection, emancipation and migration, war and peace, intervention and independence. The twentieth century witnessed epochal national transformations: from colony to republic, from dictatorship to democracy—and vice versa—from capitalism to socialism. The late twentieth century—“the Special Period in the Time of Peace”—was a time of still more change. Not since the early 1960s were existing value systems subject to as much pressure as they were during the 1990s, when a belief system unable to sustain faith in the political order upon which it rested could no longer plausibly command moral credibility. It was not a question of if change would come, or even when it would come: change was necessary, immediately, and on that matter Cubans were unanimous. Simply put, things had to change. The only questions were how much would change, at what speed, and with what result.

This edition of On Becoming Cuban goes to press nearly a decade after the appearance of the original publication and fifty years after the triumph of the Cuban revolution. Into the twenty-first century the specter of change was the problematic of the Cuban future. It was implied in the persistent question, “What will happen after Fidel dies?” The presentiment of change meant that vast numbers of Cubans lived their lives in a state of waiting: some waited in hopeful anticipation of impending change, others waited in dread of change. Cubans resigned themselves to a condition of anticipation, waiting for change, waiting for something to happen, even as they went about engaged in the most routine activities of daily life—all a matter of change certain to come, portending an uncertain outcome.

These conditions had far-reaching cultural implications. They reached deeply into the psychology of a people. Men and women across the island were required to develop new survival strategies, to question the efficacy of the assumptions and commitments that had previously informed everyday life, and inevitably to devise new ways — inventar was the verb of choice—to negotiate the changing material circumstances and the new moral order of their time.

This book considers the ways that vast numbers of Cubans engaged the condition of change in their daily lives, as a matter of a constant process of adjustment and adaptation, by way of relentless negotiations to get by and do better, to develop adequate coping mechanisms and shape appropriate survival strategies, to fashion ways to make life easier and, in the end, to obtain a measure of happiness.

Not necessarily a remarkable endeavor, of course: it is what engages the vast portion of humanity. The Cuban case was particularly intriguing in the sense that very early Cubans found themselves deeply implicated in, and at times inexorably drawn into, the material environment and moral systems of North American origins, circumstances that contributed to shaping the people that Cubans have become. The United States influenced decisively the meaning of Cuban, providing a government to resist, hence a factor of national identity and means of self-definition, and a culture to embrace and adapt, hence a means and measure of well-being.

To contemplate Cuba at the beginning of the twenty-first century is to reflect on patterns of the past as portents of the future at a time when the presentiment of change is palpable. It is on such occasions of change, of course, in the process of adaptation and adjustments, when a people are most susceptible to outside influences—specifically, when the internal paradigms around which daily life have been previously organized reveal themselves wanting and external ones offer the promise of a better life. So it was in Cuba at the start of the twenty-first century, as it had been at the start of the twentieth century.

The difficulty lies in making sense of these developments, not as a way to predict outcomes but rather as a way to contemplate possibilities. It is almost impossible not to marvel at the similarities over the span of two centuries. All through the second half of the twentieth century — just as in the second half of the nineteenth century — vast numbers of men and women emigrated in the hope of finding a way to a better future somewhere else. Cuba seemed unable to guarantee them a future commensurate with their expectations, and they departed in search of the future in other lands. In the final years of the twentieth century, an estimated 10 percent of the Cuban-born population lived abroad, mostly in the United States; in the final years of the nineteenth century, approximately 10 percent of the Cuban-born population had taken up residence in the United States. Cuba at the end of the twentieth century experienced conditions not dissimilar to circumstances at the close of the nineteenth century: diminished production, deteriorating infrastructure, declining fertility rates, disrupted transportation, abandoned factories, deserted fields and farms.

What these circumstances implied for the future of Cuba, and especially for the impact of North American cultural forms in Cuba, was impossible to predict, of course. But the developments were suggestive, and given the historical trajectory along which this book traverses the years between the 1850s and the 1950s, the portents were intriguing. The patterns of past change suggest the parameters of future change.

By the early twenty-first century, the Cuban relationship with the United States seemed to have gone full circle. North American influences had insinuated themselves into Cuban daily life in the most subtle and often in the most improbable ways. Between the late 1990s and early 2000s a flash of the future revealed itself. The value of U.S. exports to Cuba increased steadily, from $30 million in 2001 t...

Table of contents

- The Louis A. Perez Jr. Cuba Trilogy, Omnibus E-book

- The War of 1898

- On Becoming Cuban

- Cuba in the American Imagination