- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

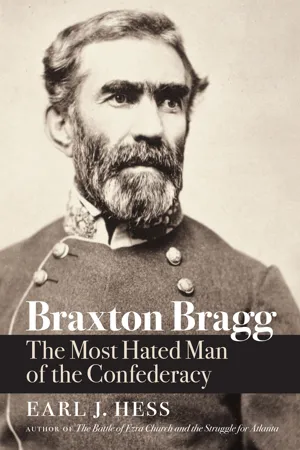

As a leading Confederate general, Braxton Bragg (1817–1876) earned a reputation for incompetence, for wantonly shooting his own soldiers, and for losing battles. This public image established him not only as a scapegoat for the South’s military failures but also as the chief whipping boy of the Confederacy. The strongly negative opinions of Bragg’s contemporaries have continued to color assessments of the general’s military career and character by generations of historians. Rather than take these assessments at face value, Earl J. Hess’s biography offers a much more balanced account of Bragg, the man and the officer.

While Hess analyzes Bragg’s many campaigns and battles, he also emphasizes how his contemporaries viewed his successes and failures and how these reactions affected Bragg both personally and professionally. The testimony and opinions of other members of the Confederate army — including Bragg’s superiors, his fellow generals, and his subordinates — reveal how the general became a symbol for the larger military failures that undid the Confederacy. By connecting the general’s personal life to his military career, Hess positions Bragg as a figure saddled with unwarranted infamy and humanizes him as a flawed yet misunderstood figure in Civil War history.

While Hess analyzes Bragg’s many campaigns and battles, he also emphasizes how his contemporaries viewed his successes and failures and how these reactions affected Bragg both personally and professionally. The testimony and opinions of other members of the Confederate army — including Bragg’s superiors, his fellow generals, and his subordinates — reveal how the general became a symbol for the larger military failures that undid the Confederacy. By connecting the general’s personal life to his military career, Hess positions Bragg as a figure saddled with unwarranted infamy and humanizes him as a flawed yet misunderstood figure in Civil War history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Braxton Bragg by Earl J. Hess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1: The Making of a Southern Patriot

Braxton Bragg came from a successful middle-class family in the Upper South. His father Thomas Bragg owned slaves and made a living by contracting the construction of various buildings in the state. Born in Warrenton, North Carolina, on March 21, 1817, Braxton had eleven brothers and sisters. The eldest, John, graduated from the University of North Carolina and served in the U.S. Congress and as a judge in his adopted state of Alabama. Thomas Bragg Jr. graduated from Captain Partridge’s Military Academy in Middleton, Connecticut, and later served as governor of North Carolina and attorney general of the Confederate government. Brother Alexander was an architect, Dunbar was a merchant in Texas, and William, the youngest son, was killed in the Civil War. Thomas Bragg Sr. fathered six daughters as well.1

A tragic incident accompanied the family history. Braxton’s mother, Margaret Bragg, shot and killed a free black man who apparently spoke impertinently to her one day. She was arrested and held in jail for a while before being acquitted in a jury trial. The exact date of this incident remains unclear, leading some historians to speculate that she may have been pregnant with Braxton at the time. Moreover, historians have also speculated that the incident made an impression on the young Braxton when he became old enough to understand it. Grady McWhiney states that “this unquestionably affected Braxton.” “Consciously or subconsciously he may have been ashamed of his mother’s jail record,” McWhiney continued, even though there is no evidence to support such a conclusion. This incident seems the only explanation for Bragg’s sensitivity and fierce resolve to prove his standing in society, in McWhiney’s view.2

One ought to be able to support such a conclusion with documentary evidence, but there simply is none to use in this argument. Bragg’s many battles with other men throughout his life do not need such a hypothetical explanation, for there are many other ways of interpreting that part of his contentious personality.

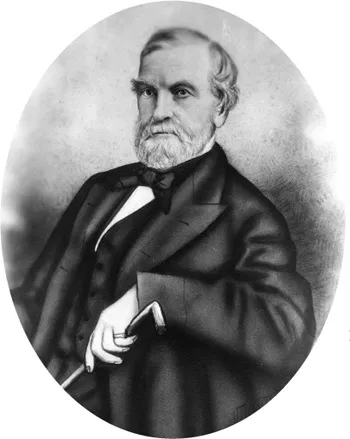

THOMAS BRAGG SR. A builder and contractor in North Carolina, Bragg fathered five sons and six daughters. One son, John Bragg, served in the U.S. Congress; another, Thomas Bragg Jr., was governor of North Carolina and attorney general in the Confederate government; and Braxton Bragg was a full general in the Confederate army. (Bragg Family Photographs, ADAH)

Bragg’s lot in life was a military career; it suited him professionally and temperamentally, and he became a superb soldier. After graduating fifth in a class of fifty cadets from the U.S. Military Academy in 1837, the very year that the Second Seminole War broke out, his first assignment was in Florida to fight Native Americans as a second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery. The next year he became seriously ill and never fully recovered from the effects of malaria. In fact, the young lieutenant was given a sick leave in 1838 to recuperate before returning to duty.3

Although Bragg saw no combat in Florida or during his participation in Indian Removal, his professional advancement was impressive. He served as adjutant of his artillery regiment and was promoted to first lieutenant on July 7, 1838, captain eight years later, major in 1846, and lieutenant colonel dating from the battle of Buena Vista in 1847.4

But Bragg’s rise was not without trouble. His contentious personality came to the fore within the context of soldiering. Because he had a strong tendency to analyze the army’s system and find it wanting, he often wrote testy letters to officers as well as politicians who might be interested in reforming the military establishment. While serving at various posts, Bragg became acquainted with many other officers and developed friendships with some, including William T. Sherman. But he also rubbed many other colleagues the wrong way. Erasmus D. Keyes remembered Bragg from their mutual service in South Carolina as ambitious, “but being of a saturnine disposition and morbid temperament, his ambition was of the vitriolic kind.” Keyes recognized that Bragg was intelligent “and the exact performance of all his military duties added force to his pernicious influence.”5

Keyes also recalled that Bragg had already developed into a fierce defender of his native region by the mid-1840s. “He could see nothing bad in the South and little good in the North, although he was disposed to smile on his satelites and sycophants wheresoever they came.” Keyes failed to get along with Bragg because the Northerner was “not disposed to concede to his intolerant sectionalism.” Forty years later, Sherman recalled an incident wherein he mediated to prevent a duel between Bragg and a correspondent of the Charleston Mercury. The newspaperman disparaged North Carolina while making a toast at an Independence Day banquet in 1845, calling it a “strip of land lying between two States.” Bragg challenged him to a duel. Friends asked Sherman and John F. Reynolds to stop it, and Sherman was able to convince the correspondent to “admit that North Carolina was a State in the Union, claiming to be a Carolina, though not comparable with South Carolina.” Sherman recalled this incident with a good deal of sardonic humor, but it is obvious that Bragg’s hotheaded defense of his home state nearly resulted in bloodshed.6

Bragg was ready, in short, to take on all comers. He certainly had no hesitation in taking on the U.S. Army. The young officer wrote a series of nine articles that were published in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1844–45, all of them highly critical of army administration and organization. He did not spare certain high-level individuals as well. Although Bragg signed these articles “A Subaltern,” it soon became common knowledge that he was the author. The person targeted for the most criticism was Winfield Scott, general-in-chief of the army. Many of Bragg’s suggested reforms were needed, but the tone of his articles was very unkind and unprofessional. That tone brought nothing but trouble. Bragg applied for a leave of absence, being deliberately vague about its purpose, and used it to travel to Washington, D.C., in March 1844. There he lobbied various congressmen regarding his proposed army reforms. When the adjutant general learned of this, he ordered Bragg to leave, but the ambitious young man refused and continued his lobbying efforts, testifying before a congressional committee. Bragg was arrested, tried, and found guilty of disrespect. Unfortunately, he was given a light punishment, and it failed to instill any sense of regret or repentance.7

Grady McWhiney has aptly written of “Bragg’s distinction as the most cantankerous man in the Army. He had been court-martialed and convicted; he had been censured by the Secretary of War, the Adjutant General, and the Commander of the Eastern Division. No other junior officer could boast of so many high ranking enemies.”8

The Mexican War offered Bragg a distraction from his obsession with military reform. He commanded one of only two light batteries in the army, joining Zachary Taylor’s field force in southern Texas in 1846. His unit participated in Taylor’s capture of Monterey in September of that year, but the battle of Buena Vista on February 23, 1847, created national fame for the young officer. Outnumbered three to one, Taylor’s army of mostly untried volunteer troops was sorely pressed. If not for the steadiness of the few regular units, the American position might well have collapsed. The widely circulated story that Taylor encouraged Bragg by telling him to fire “a little more grape” is certainly apocryphal. Bragg himself later told acquaintances that Taylor really said, “Give them hell!”9

Buena Vista marked the beginning of Bragg’s relationship with Jefferson Davis, whose Mississippi regiment did well in the battle. In his official report, Davis praised Bragg’s handling of the guns: “We saw the enemy’s infantry advancing in three lines upon Capt. Bragg’s battery; which, though entirely unsupported, resolutely held it’s position, and met the attack, with a fire worthy of the former achievements of that battery, and of the reputation of it’s present meritorious commander.” In fact, Davis moved his Mississippians to support Bragg and helped the artillery drive away yet another Mexican attack.10

Bragg praised Davis’s regiment as one of the few reliable volunteer units with Taylor’s army. In general, his criticism of volunteers was deep and intense. Humphrey Marshall had graduated from West Point but commanded volunteers in Mexico. “He was at Buena Vista,” Bragg told his brother John, “where his regiment did some fine running & no fighting, as all mounted volunteers ever will do. He is a great humbug and a superficial tho fluent fool.”11

The fame accorded Bragg at Buena Vista did not turn the officer’s head. He continued to serve dutifully even though suffering “two severe attacks” of malaria in the summer of 1847. During this time period one of Bragg’s artillerymen tried to kill him, but the motive remains obscure. Samuel B. Church placed a loaded and fused twelve-pounder shell outside Bragg’s tent on August 26, 1847. Although exploding only two feet from the sleeping officer, the shell failed to injure him. At the time no one knew who planted the bomb, and Church was free to try another in October 1847 but failed again. He later deserted the battery and was hanged as a horse thief.12

ELISE BRAGG. Commonly known as Elise, Eliza Brooks Ellis was born in Mississippi and lived on the family’s Evergreen plantation near Thibodeaux, Louisiana. She and Braxton Bragg married in 1849. (Confederate Veteran 4 [1896]: 103)

Buena Vista fame translated into social advancement for Bragg. He was greeted as a hero in many Southern cities after the war, and it was during one such reception that he met his future wife. Eliza Brooks Ellis, more familiarly known as Elise, was the oldest daughter of Richard Gaillard Ellis and Mary June Towson Ellis. She had been born in Mississippi and was for a time a schoolmate of the future Mrs. Jefferson Davis. The family estate, a sugar and cotton plantation called Evergreen, was located in Terre Bonne Parish, Louisiana. Elise met Bragg at a ball given in his honor at Thibodaux, forty miles west of New Orleans. The couple was married on June 7, 1849.13

Soon after her marriage, Elise confided to a correspondent that she initially believed Bragg was a bit too reserved and cold, but she had been attracted by his strong character and commitment to the truth. Now that she had come to know him better, Elise was surprised by the “depth of affection” that lay behind “such an exterior—he is an ardent & devoted husband.” Bragg fully reciprocated her feelings. He wrote of his longing for her upon leaving to attend court-martial proceedings six months after their wedding. “My first thought is for you . . . what in this world can make a man so happy, especially when he possesses such a wife.”14

Bragg’s army career after Mexico became more complex, and he was shifted around to a number of army posts largely along the frontier, causing numerous separations from Elise. He continued to criticize high-level administrators in the army and in the executive branch of the national government and pushed for army reform, hoping for a time that his brother John could capitalize on his tenure in the U.S. Congress to aid the cause. As with the Subaltern articles, his ideas made sense. Now, however, he pursued them with more tact and less bristle. Bragg also proved loyal to trusted subordinates and colleagues. He wrote glowing letters of recommendation for George H. Thomas and Daniel Harvey Hill, both of whom had served in his battery. Given the bitter controversy that erupted between Bragg and Hill growing out of the Chickamauga campaign, it is interesting to see that Bragg referred to him as “my young friend” in 1848. He praised Hill as “without a superior for gentlemanly deportment and high moral character.” Bragg also thought very highly of Henry J. Hunt, another friend of the post-Mexico era, who, like Thomas, would fight in the Union army.15

Numerous partings with Elise were hard to bear. “I am lost without you, dear wife,” he wrote from Fort Leavenworth in June 1853. Bragg often complained that he rarely heard from his numerous siblings. What Bragg called “my old Florida complaint of the liver” continued to trouble him. “Every summer I have these attacks, and I can . . . only keep about by almost living on Mercury (Blue Mass & Calomel). No constitution can stand it,” he told his friend Sherman. An undated prescription “for Chronic Chill & fever,” written in Bragg’s hand but coming from a doctor in North Carolina, probably relates to this time period in the officer’s life.16

By the mid-1850s Bragg’s army career reached a crisis point. Jefferson Davis, as secretary of war in the Franklin Pierce administration, instituted significant army reforms. One of them involved introducing rifled artillery and phasing out light batteries. Bragg was devastated by the decline of efficiency in his battery, and he was ordered to join a cavalry regiment on the frontier. The distant but respectful relationship between Bragg and Davis now became bitter, with the officer sarcastically referring to the secretary as “our friend” in his correspondence. Bragg resigned his commission in the U.S. Army on January 3, 1856, “disgusted & worn down” as he told a correspondent. Davis was “absolutely bent on substituting long range rifles for Light Artillery, though nominally keeping it up at a heavy expense.” As a result, “my command was destroyed, my usefulness gone. . . . The finest battery I ever saw was destroyed in two years at a cost of $100,000.”17

As Grady McWhiney...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures and Maps

- Preface

- Chapter 1 : The Making of a Southern Patriot

- Chapter 2 : Pensacola

- Chapter 3 : Shiloh

- Chapter 4 : Corinth and High Command

- Chapter 5 : Kentucky

- Chapter 6 : Controversy and Recovery

- Chapter 7 : Stones River

- Chapter 8 : Turning Point

- Chapter 9 : Tullahoma

- Chapter 10 : Chickamauga

- Chapter 11 : Revolt of the Generals

- Chapter 12 : Chattanooga

- Chapter 13 : Military Adviser to the Confederate President

- Chapter 14 : Davis’s Troubleshooter

- Chapter 15 : Defeat

- Chapter 16 : After the War

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index