- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Kottick presents technical information in an accessible, but entertaining, way: the forms and styles of harpsichords, advice on purchasing decisions, maintenance techniques (such as voicing, regulating, and changing strings, tongues, plectra, springs, and dampers), aids in troubleshooting common problems, and detailed instructions on tuning and temperament. As builder of some thirty keyboard instruments, Kottick is well qualified to speak on the subject.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

The Harpsichord and Its History

Chapter 1

How the Harpsichord Works

Explaining how the harpsichord works seems simple. A key is pressed. The back of the key rises, pushing up a jack from which protrudes a plectrum. The plectrum plucks the string, which vibrates. These vibrations are transmitted to the soundboard. In turn, the soundboard vibrates, radiating sound throughout the room and to the listener.

Obviously these few words of explanation beg the question. Although it may be convenient to think of the harpsichord in such elemental terms, it is not a straightforward tone generator. It is a complex mechanism, designed to convert mechanical energy into pressure waves, which, in turn, are transmitted to people’s ears through a gaseous medium composed mostly of nitrogen and oxygen. Thus, it is a sound-producing device that must be considered mechanically, acoustically, and physiologically. Although we do not know nearly enough about it, we do have more information than those few opening sentences give us. Nevertheless, all the topic headings needed for a detailed discussion of how the harpsichord works are present in that opening paragraph, and it is by means of these key words—keyboards, jacks, strings, soundboard, room, and listener—that this chapter will proceed.

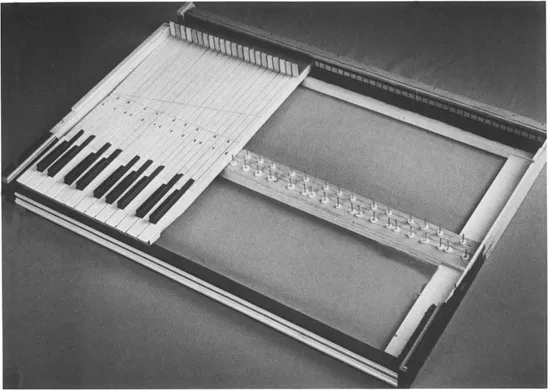

KEYBOARD

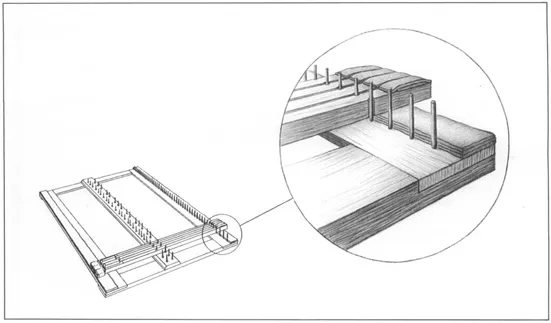

A keyboard begins with a keyframe—literally a “frame” of wood, with two end pieces and usually three cross pieces. The middle crosspiece is the balance rail. Balance pins are driven into it, and a cloth or felt bushing (balance punching) is placed on each pin. These are the fulcrums on which the keys pivot. The backs of the keys rest on the padded back rail (Figure 1-1). The fronts of the keys may or may not contact the front rail, depending on the way in which the action is stopped.

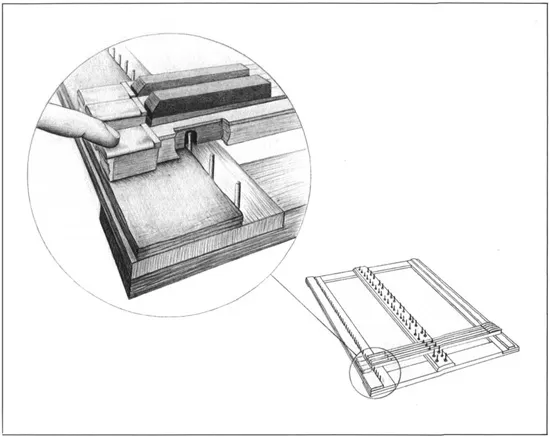

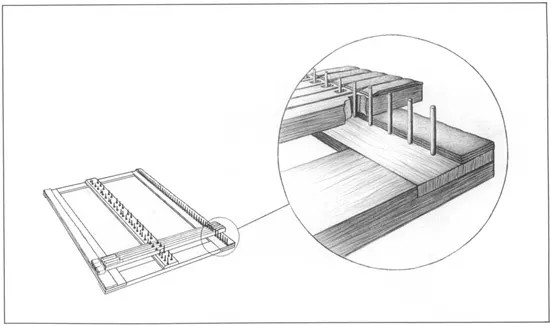

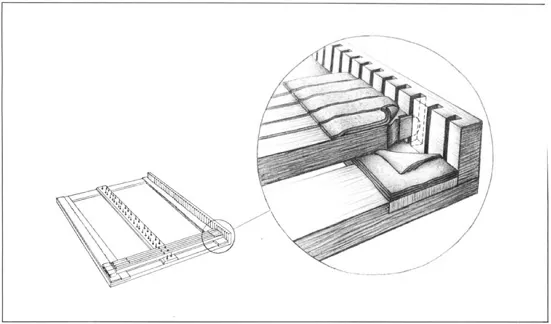

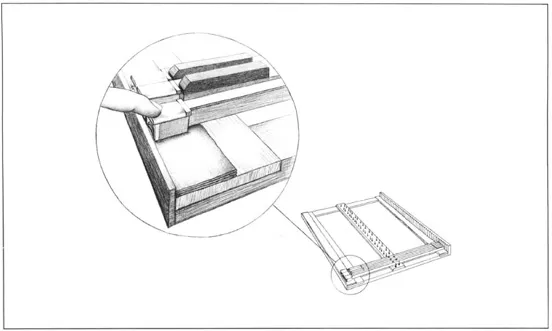

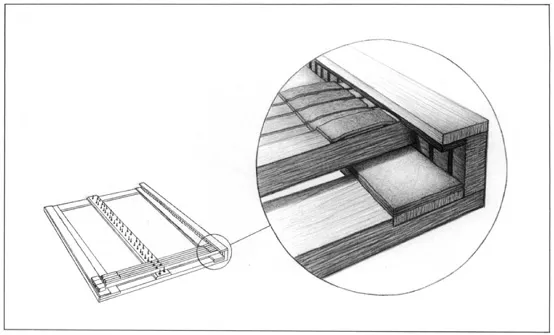

A key needs to be guided at two points, or else it will swivel like a compass needle. The balance pin provides the first point, and the second can be either at the head of the key or at the rear. The English seem to be the only ones who provided a guide pin that operated in a hole drilled under the head of the key (Figure 1-2). Rear guides can be either guide pins that run through holes in the backs of the keys (as on the upper manuals of French harpsichords (Figure 1-3), pins that run between the backs of the keys (as on many bentside spinets, Figure 1-4), or they can be rack guides (as on Italian and Flemish harpsichords). A rack guide consists of another rail, called the rack, fastened upright to the rear of the back rail. Slots are cut into the rack, and a metal pin or a slip of wood, bone, or plastic, protruding from the back of each key, is inserted into the slot and is guided by it (Figure 1-5).

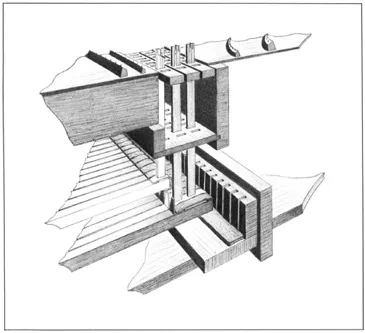

FIGURE 1-1. Typical keyframe.

The dip of the keys, that is, the distance they descend when pressed down in playing, is a crucial element of regulation, affecting both the player’s comfort as well as his ability to perform rapid passage work. Key dip is set according to one of the three ways in which the action may be halted: by head stop, rack stop, or jackrail stop. In the first, normally found on Italian and English harpsichords, the motion of the key is stopped when the bottom of the head of the key meets the front rail, which is appropriately padded. Key dip is regulated at this juncture, with more padding giving a shallower dip (Figure 1-6). In a rack stop, as found on Flemish instruments, the top of the rear end of the key is stopped with a padded touchrail fastened to the top of the guide rack. Key dip is regulated either by the amount of padding sewn to the touchrail, or by adjusting the height of the touchrail (Figure 1-7). Finally, the action may be stopped when the tops of the jacks contact the padded inner surface of the jackrail. This is the manner in which the manuals of a French harpsichord are stopped, and dip is regulated by the amount of padding on the jackrail or by adjustment of the rail’s height.

The upper keyboards of two-manual harpsichords differ little from the lower, except that the key levers are shorter and the keyframe often does not have a front rail. French double-manual harpsichords have a coupling mechanism, in which either the top manual slides in or the bottom manual pulls out. This brings some dogs, which are wood posts mounted at the ends of the lower manual keys, in contact with the bottoms of the rears of the upper manual keys, thus pushing up those keys and their jacks when the lower manual is played. This allows the front 8' to be added to the sound of the back 8'; uncoupled, only the back 8' (considering the two 8's only) is available from the lower manual. Figure 1-8 should make this description clear. English, and most of the classical Flemish double-manual harpsichords do not couple; instead they use a dogleg action (not to be confused with coupler dogs). It is given this strange name because the front 8' jack (which, with a determined effort, could be imagined to look like a dog’s leg) has a step cut into it so that it can be lifted at one of two points; thus, dogleg jacks can be operated from either the upper or the lower manual, and both 8's are available on the lower manual. The front 8' can be shut off by moving its register, but then it cannot be played from either manual (Figure 1-9).

FIGURE 1-2. Keys guided by pins under the key head.

FIGURE 1-3. Keys guided by pins through the backs of the key levers.

FIGURE 1-4. Keys guided by pins between the backs of the key levers.

FIGURE 1-5. Keys guided by slips in a rack.

FIGURE 1-6. A head stop.

FIGURE 1-7. A touchrail stop.

A light, responsive action is desirable in almost all harpsichords. For this reason, builders usually attempt to keep the mass of the keys as low as possible commensurate with the touch desired. Keys are often balanced by carving wood out of the front as well as by adding weight to the rear (Figure 1-10). The position of the balance points is also important, since it affects not only the balance of the keys, but also the effort needed to depress the keys, the extent of the dip, and the velocity with which the plectra pluck the strings.

The tops of the key fronts are covered with a variety of materials. Italian harpsichords normally have boxwood naturals, but sometimes ivory or bone. Sharps are made of fruitwood, often stained and covered with slips of ebony. Flemish instruments usually have bone naturals, with oak or fruitwood for the sharps. French keyboards use ebony naturals and sharps, but the sharps are covered with slips of bone. English harpsichords cover the naturals with ivory, and their sharps are stained black. These are, of course, generalizations, and exceptions abound.

JACKS

While appearing to be rather simple objects, jacks, like keyboards, are fabricated with a high degree of sophistication. They could be thought of as the heart of the harpsichord’s mechanical system, since it is the jacks that translate the motion of the fingers on the keys into the pluck of the strings.

FIGURE 1-8. French coupler action.

FIGURE 1-9. English dogleg action.

FIGURE 1-10. Keys balanced by carving wood out of the front.

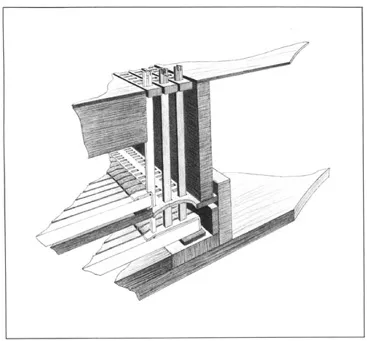

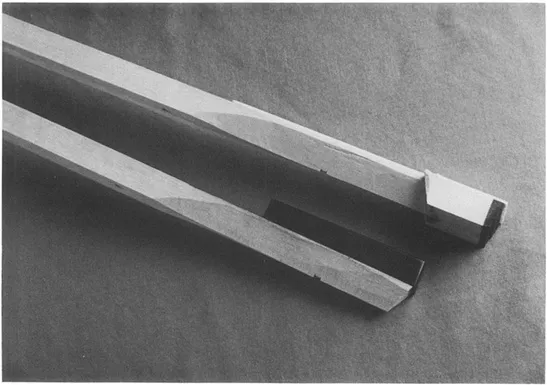

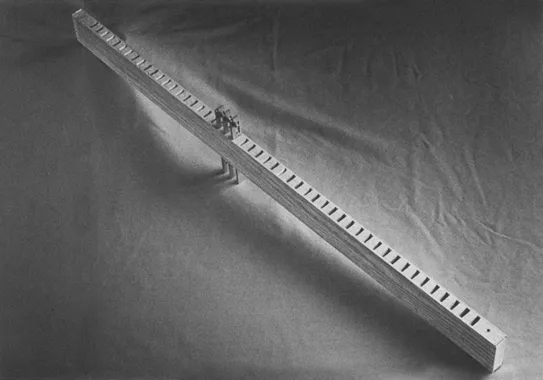

Jacks are supported in guides, or registers, which are thin, narrow lengths of wood, approximately 3/8" thick and ¾" wide, that are found in the gap between the wrestplank and the bellyrail. The registers are slotted to admit the jacks (the French practice was to make the slots oversize and to cover the register with leather, which was then slotted to the size of the jacks). Terminology is somewhat imprecise here. The words “guide” and “register” are often used interchangeably, even though the word “register” also refers to the sound and/or the mechanism of a choir of strings, as in “the back 8' register has a mellow sound.” Furthermore, the word “slide” is sometimes used to distinguish a movable upper guide from a fixed lower. A separate guide is required for each row of jacks. Italian harpsichords and bentside spinets have registers called box guides—bars of wood some two inches deep through which slots are cut. Box guides combine the functions of upper and lower guides (Figure 1-11).

On harpsichords with more than one set of strings, some of the registers are made so that they can be turned on or off. This is done by making the upper guide movable end to end, with just enough motion so that the plectrum either misses the string (register off) or plucks it (register on) when a key is depressed and its jack is raised. The guides are moved either by levers found on the wrestplank (as on many German harpsichords), or by levers that come through the name board (as on later French harpsichords); otherwise, the ends of the guides themselves project through the cheek of the case (as on earlier Flemish harpsichords and 1×8', 1×4' Italians). Nonmovable guides are found only when there is one set of jacks on a manual, as on the upper manual of a French harpsichord, or on a single-strung instrument like a virginal.

FIGURE 1-11. A box guide.

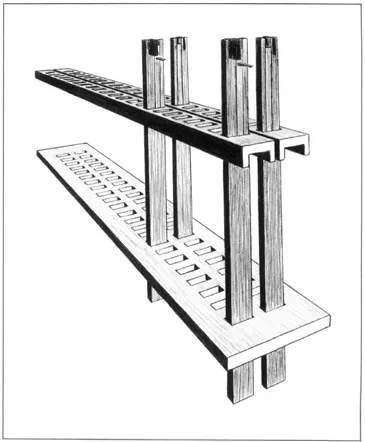

Northern harpsichords have separate upper and lower guides: the lower, just over the keys, is fixed, and the upper, at the level of the soundboard, is normally capable of on-off motion. Separate upper guides are necessary so that individual registers can be turned on or off independently, but the lower, fixed guide can be one piece, combining all the slots of the two or three upper guides into one member (Figure 1-12).

Modern jacks are made of either wood or plastic. Although a number of woods are suitable, European varieties of pear and apple proved themselves centuries ago as excellent materials for jacks. They are of medium density, easy to work, and have smooth, close grains. Most wooden jacks are still made from them. A jack has a wide slot cut through it at the top, into which is set the tongue, usually made of holly. The jack also has another, narrower slot in which the damper cloth is wedged. A mortise is cut through the top of the tongue to receive the quill. At appropriate points a hole is drilled through the jack, and a slightly larger one through the tongue. An axle, usually made from a pin, is driven through the assembly, and the tongue is now free to swivel in the slot. Another two holes are drilled in the jack, beneath the tongue, and a spring of boar bristle, plastic, or wire is inserted here (the Italians often used a thin, flat brass spring instead of a boar bristle). Riding in a groove cut into the tongue, the spring insures that the tongue, displaced by the act of plucking the string, will return to its resting place.1

FIGURE 1-12. Upper (movable) and lower (fixed) guides.

The plectrum is a part of the harpsichord that has engendered many complaints over the centuries. Bird quill was used in the harpsichords of old, and experience proved that only quills made from the primary feathers of crows (sometimes ravens) were suitable. Bird quill was used for hundreds of years, but when the harpsichord was revived at the beginning of this century, hard leather was almost universally employed. Since the early 1960s a plastic called Delrin has become the preferred quilling material, and it is used by most builders.

It was said that Bach spent fifteen minutes tuning and maintaining his harpsichord every time he sat down to play; undoubtedly some of that time was spent replacing the quills, since crow quill wears out and, being organic, reacts to changes in temperature and humidity. Leather also wears out, reacts to climatic changes, is even more finicky in its adjustment, and has an additional disadvantage in that there is little historical justification for its use (aside from its specialized application in the peau de buffle). Delrin has proved to be a satisfactory substitute for quill, although there is no historical justification for it at all. Delrin work-hardens, but it has an extremely long life; if cut properly, the quills can last anywhere from several years to a decade or more. Nevertheless, cutting Delrin quills properly is a skilled procedure, and improperly cut quills can lead to many annoying problems of regulation.

There are those who insist that Delrin, properly voiced, is indistinguishable in sound and feel from crow quill, while others assert that crow quill provides an ultimate tonal flexibility that Delrin does not quite achieve. For this reason a number of builders are returning to crow quill, and others will at least supply it for customers who are willing to put up with its idiosyncrasies in return for the “ultimate experience.” But crow quill, to some extent at the mercy of the weather, and with its high breakage rate, also requires a great deal of patience.

Plastic jacks look very much like wooden jacks. Some makers give the tongue a top screw which can be used to adjust the distance by which the quill underlaps the string; some jacks have adjustable end pins; some do not have axles passing through jack and tongue, but instead have little nibs projecting from the sides of the tongue, which snap into corresponding depressions in the jack; some have springs attached to the tongue rather than the jack. Axleless jacks have an assembly that combines the function of tongue and spring. French and Flemish jacks taper in width and breadth; they are designed to fit snugly in their register slots only when the jacks are at rest. Italian jacks are usually shorter than northern jacks, and are therefore made thicker to give them a little more weight. Sometimes they are even leaded. But regardless of type, material, or accoutrements, every jack will have a tongue, spring, quill, and damper.

Let us try to visualize the events that take place when a string is plucked. As the key is depressed the jack begins to rise, and the damper, rising with it, leaves its contact with the string. After the jack has traveled about 3/32", the plectrum contacts the string, exciting it like a clavichord tangent. The resulting sound is quite faint, but quite reproducible (particularly on bass notes) by anyone who wants to explore the effect for himself. This “clavichord effect” becomes part of the sound of the harpsichord—the initial part of the tone, called the transient.2 As the pressure of the plectrum against the string increases, the plectrum begins to bend, taking a roughly parabolic shape, and the string is raised. The pressure of the string against the plectrum thus begins to contain a lateral component, tending to force the jack to one side while the string slides down the parabolic curve. Finally, the string slips off the end of the plectrum and begins to vibrate.

Momentum carries the key to the bottom of its dip, and the jack to its maximum height, where its top is stopped by the jackrail. When the key is released, the jack is lowered until the bottom of the plectrum contacts the string. In the absence of prior knowledge one would expect that this would stop the jack from descending all the way, but the plectrum is angled, and its tip is cut in such a way as to cause the tongue to swivel back, thus allowing the plectrum to go around the string. Having done its job, the tongue is returned to its resting point by the force of the spring. The jack then comes to a halt, stopped by the padding on the end of the key. At the same time the damper contacts the string, causing it to stop vibrating. The contact of the plectrum and the damper with the string both produce another sound, which is simply recognized as part of harpsichord tone. Of course, all this takes place in far less time than it takes to read about it.

STRINGS

It has been known since at least the sixteenth century that a string sounds best when it is stretched to a tension near to its breaking point. That tension is not as high for metal string as it is for gut (tuning instructions in seventeenth-century lute and gamba tutors often began by advising the player to tune the top string as high as it would go without breaking). For the sake of convenience (that is, the convenience of not having to replace broken strings on a daily basis), it is usually assumed that from a half to a whole step below the breaking point is as high as one can practically go with metal strings, and usually one goes lower than that.

Things such as the angle of side bearing, down bearing, and back pinning can also affect the breaking point. Otherwise, at what point a string breaks depends on its composition: brass, for example, breaks before iron; iron breaks before steel. The problem for the harpsichord builder, therefore, is to choose strings that can be stretched to the “proper” point, whatever that might be. Thus, knowledge about the breaking points of various kinds of wire is important. Such knowledge can also provide information about the pitch levels to which the old instruments were tuned. F...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Harpsichord Owner’s Guide

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to the Paperback Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Introduction

- Part One The Harpsichord and Its History

- Part Two Maintenance Techniques

- Part Three Troubleshooting the Harpsichord

- Part Four Care of the Harpsichord

- Epilogue The Well-Regulated Harpsichord

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Harpsichord Owner's Guide by Edward L. Kottick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.