eBook - ePub

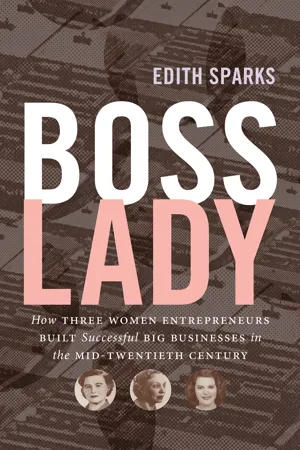

Boss Lady

How Three Women Entrepreneurs Built Successful Big Businesses in the Mid-Twentieth Century

- 326 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Boss Lady

How Three Women Entrepreneurs Built Successful Big Businesses in the Mid-Twentieth Century

About this book

Too often, depictions of women’s rise in corporate America leave out the first generation of breakthrough women entrepreneurs. Here, Edith Sparks restores the careers of three pioneering businesswomen — Tillie Lewis (founder of Flotill Products), Olive Ann Beech (cofounder of Beech Aircraft), and Margaret Rudkin (founder of Pepperidge Farm) — who started their own manufacturing companies in the 1930s, sold them to major corporations in the 1960s and 1970s, and became members of their corporate boards. These leaders began their ascent to the highest echelons of the business world before women had widespread access to higher education and before there were federal programs to incentivize women entrepreneurs or laws to prohibit credit discrimination. In telling their stories, Sparks demonstrates how these women at once rejected cultural prescriptions and manipulated them to their advantage, leveraged familial connections, and seized government opportunities, all while advocating for themselves in business environments that were not designed for women, let alone for women leaders.

By contextualizing the careers of these hugely successful yet largely forgotten entrepreneurs, Sparks adds a vital dimension to the history of twentieth-century corporate America and provides a powerful lesson on what it took for women to succeed in this male-dominated business world.

By contextualizing the careers of these hugely successful yet largely forgotten entrepreneurs, Sparks adds a vital dimension to the history of twentieth-century corporate America and provides a powerful lesson on what it took for women to succeed in this male-dominated business world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Boss Lady by Edith Sparks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Constructing Entrepreneurial Pathways

“I know you, you go do it … six months from now you’re going to be bored.” That was what the husband of Virginia Rometty, IBM’s first female CEO, said to her when earlier in her career she was offered a “big job” but worried that she did not have sufficient professional experience to be successful in it. She had “told the recruiter that she needed to think about it,” but while reviewing the opportunity that evening with her husband, he said to her, “Do you think a man would have ever answered that question that way?” While Rometty reported that the experience had taught her the importance of confidence, the story also reveals the supportive role that husbands have played in the lives of some successful businesswomen. Such emotional support can help facilitate the kind of risk-taking inherent in business leadership for which confidence is a necessary ingredient. And as Rometty has been quick to emphasize, in addition to providing emotional support, her husband has also been an equal partner in their marriage, helping to facilitate her rise to the top of corporate America.1

Rometty’s relationship with her husband and the role his support and household participation have played in her success are emblematic of female business leaders more generally at the beginning of the twenty-first century. In fact, for many women in the upper echelons of the business world, marriage plays an important role in both their success and persistence, according to a variety of sources. One Harvard Business Review article titled “Manage Your Work, Manage Your Life,” for example, reported that “many of those [executives] we surveyed consider[ed] emotional support the biggest contribution their partners have made to their careers.”2 But in other studies, the division of household labor is the focus and husbands are singled out for the impact their willingness or resistance to participate has on married women’s professional careers and success. The 2014 national bestseller Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, for example, includes a chapter titled “Make Your Partner a Real Partner,” which documents the importance of sharing the work of house and family to women’s success and encourages men to “lean in” to parenting. When professional women have husbands who do not share the work, it has a negative impact on their careers. In fact, a variety of research studies make clear that at the beginning of the twenty-first century, few women who are married to men will retain demanding professional jobs and remain married if they do not have the active support of their partners—both in the form of encouragement and participation in the day-to-day work of their household and parenting if they have children.3 Thus, husbands figure prominently in the biographies of many married female business leaders at the beginning of the twenty-first century for the ways they help or hinder their wives’ success.

This chapter takes up that topic—marriage and male family members—and examines the role both played in the careers of female entrepreneurs almost three-quarters of a century earlier, but not as sources of emotional support or household partnership. In fact, it is unlikely women received both or either of these forms of support from male relatives at this time in history. Rather, for women in the middle of the 1900s, marriage and male family members were stepping stones on the pathway to entrepreneurial opportunity.

Tillie Lewis, Olive Ann Beech, and Margaret Rudkin all provide examples of how successful mid-twentieth-century female entrepreneurs in large-scale manufacturing companies carved out a place for themselves at the top of the American business world by leveraging their relationships with the men in their personal and professional lives. This is different from arguing that men gave their wives [or sisters-in-law, in Lewis’s case] a leg up. That was true too. But the goal here is to understand the way in which this generation of women, hampered by marriage bars, professionally crippling domestic expectations, and lack of access to higher education (none of the three received a college education, let alone an MBA), made the most of their relationships with male family members to plot their paths into business leadership and ownership.

For female entrepreneurs, who carry responsibility for a business’s success or failure as opposed to female business professionals who manage it, connections gained through male relatives have been an especially important avenue to opportunity and success, and this is even clear in the lives of women at the start of the twenty-first century. Family studies scholars, for example, have coined the term “spousal social capital” to capture the “resource and interpersonal transactions” that entrepreneurial spouses provide and that studies confirm have a measurable impact on the sustainability of the firm. These include everything from time invested to participation in decision-making and representing the firm in the community. Wives have long played such a role in their husbands’ businesses, often unnamed in official records yet essential in day-to-day operations. But women have often not been able to count on that same support from husbands and other male relatives. In fact, researchers theorize that because female entrepreneurs tend to have “less involved spouses during firm creation” relative to men, this may help explain what others have labeled the underperformance of woman-owned ventures.4 Spousal contacts make a difference to female entrepreneurs too. For example, educated middle- and upper-class white women in the United States enjoy access to social capital and investors as an advantage of marriage because their husbands are likely to be employed professionally and to have connections to networks of power and privilege.5 Thus, husbands’ involvement, and their willingness and ability to share valuable connections, has tangible impact and can make a measurable difference in facilitating married women’s entrepreneurship and success.

Studies of women entrepreneurs in American history have confirmed that marriage has played an important role in facilitating women’s access to business ownership. Married and formerly married (widowed and divorced) women have constituted the majority of all female business owners, a finding that is consistent across several studies of women in colonial America up through the early twentieth century. They gained experience and expertise by working in businesses owned by their husbands, accessed capital through their husbands’ income and property, and inherited their businesses when they died. The influence of a husband, however, was not always advantageous, as individual stories of profligate, foolhardy, and controlling spouses reveal. And during the nineteenth century, marriage also restricted women’s legal independence, including their ability to own property and enter into contracts, both common aspects of entrepreneurship; this remained true in many states and hampered women’s ability to “conduct business in their own name” until the laws were changed. Yet even then, as widows (or formerly married women), female business owners in the nineteenth century tapped into marital property and capital to independently operate enterprises now accessible because of their new status as “sole” traders. Thus, in spite of the important ways in which marriage restricted women’s economic enterprise, in general historians of businesswomen agree that marriage also facilitated entrepreneurial opportunities for women by providing them access to capital and experience.6

Yet while a husband’s resources might have provided access to entrepreneurship, women had to seize that opportunity. The frequency with which women married to business executives with contacts and capital did not launch entrepreneurial business careers clearly makes this point. Thus, to study mid-twentieth-century female entrepreneurs is to study women who actively pursued the opportunities before them to create pathways into business ownership.

For Lewis, Beech, and Rudkin, this was certainly true—all three leveraged the contacts, capital, and opportunities their husbands and other male family members provided to gain entry into the business world and business ownership. Lewis married a wholesaler and, while working in the business he owned jointly with several of her male relatives, gained experience and contacts that she used to launch Flotill Products. And both Olive Ann Beech and Margaret Rudkin were hired as secretaries to the men who later became their husbands and business partners and whose professional stature and contacts opened the doors to business ownership. But all three women walked through those opened doors themselves, leveraging their marital relationships and relationships with male relatives to create their own opportunities.

On the one hand, this is a familiar—even a clichéd—story. Marrying into opportunity is a literary trope with a long history and has been a driver of women’s (and men’s) social mobility over several decades. Stories about “office wives” abounded in the 1920s and 1930s—female secretaries who conducted the “housework of [the] business” for their male bosses in sociologist C. Wright Mills’s conception and became romantically and sexually entangled with them in fictional accounts such as Faith Baldwin’s The Office Wife (1930).7 And historians have documented that during this period a popular conception was that unmarried women secured secretarial jobs in order to find husbands.8

But the history of female owners of large-scale businesses in the mid-twentieth century is not a story about “gold diggers” or sexual trysts but about the ways in which women leveraged marriage to access business entrepreneurship and leadership. As biographical accounts reveal, most successful businesswomen of the era gained opportunities through their husbands or other family members. Fortune’s 1973 article on “The Ten Highest-Ranking Women in Big Business,” for example, reported that with only two exceptions, the executives featured “were helped along by a family connection, by marriage, or by the fact that they helped to create the organizations they now preside over.” Though the article puts the emphasis on the help these women received rather than the opportunities they seized, it’s clear that they actively pursued their leadership roles. As Dorothy Chandler of the Times Mirror Co. reported in the article, “If I had not been Mrs. Norman Chandler, I would not have had the opportunities I’ve had.”9 The opportunities were associated with her married name, but the achievements were all Dorothy’s.

Access to social capital was particularly key for women breaking into the male-dominated manufacturing fields Lewis, Beech, and Rudkin occupied, and male family members provided that connection. On the one hand, this did not distinguish them from men. Historian Pamela Laird, author of Pull: Networking and Success since Benjamin Franklin (2006), explains: “What the rare rags-to-riches story and all success stories prove … [with] no exception [is] … the necessity for connections and connectability—the rule of social capital.”10 But studies have shown that for women, social capital—access to mentors, networks, and information—has been a critical factor in “how and why [they] gain access to top leadership positions.”11 For female entrepreneurs in particular, breaking into industries in which few women have succeeded, connections to key players signaled expertise and legitimacy. One study of present-day entrepreneurship, for example, finds that this is even more important for women than it is for men. This is because they face a variety of barriers, especially in male-dominated industries, including doubts about their abilities and prospects for success—a particular problem when it is a perspective held by funders. Today, displaying ties to those perceived as “experts” in the industry—or “expert capital”—leads to strategic capital investments and venture longevity for female entrepreneurs because they are perceived as legitimate.12 For female entrepreneurs in the mid-twentieth-century United States, “expert capital” required associations with men of influence and/or experience. Most times male family members in the business world provided this legitimacy; other times ties to leading men in the industry with whom female business leaders cultivated connections through family members or family responsibilities provided it. Either way, integrating “experts” into their social capital networks was a key step in their entrepreneurial pathways.

Privilege paved the way toward entrepreneurship and leadership for all three women too—another corollary of the ties they forged and leveraged through marriage. As is still true today, economic status afforded a degree of autonomy out of reach for most other women. For Lewis, this meant independent investments and travel—the latter tied also to the professional advantages of childlessness for women. Beech and Rudkin, on the other hand, both mothers of young children, used their wealth to craft versions of motherhood that relied on full-time, live-in childcare as well as other helpers to free them to devote time, energy, and attention to their businesses. In interesting, important, and different ways, however, mothering and working overlapped for both of them, revealing the ways in which the separate identities and categories of labor we’ve imagined for mid-twentieth-century women were less clearly defined in the day-to-day lives of female entrepreneurs. Corporate jobs and motherhood were not irreconcilable for these women, but the “competing devotions” of career and family did collide. They mediated these conflicts by fashioning a version of motherhood that capitalized on pre–baby boom parenting definitions not yet saturated with what historian Jessica Weiss has called the “quest for togetherness” and relying on their wealth, allocating much of the work of day-to-day mothering to round-the-clock helpers.13 Thus, wealth and the privileges it afforded, including social capital, all initiated through marriage and connections to male family members, enabled these mid-twentieth-century women to construct entrepreneurial pathways into positions of leadership and influence.

Tillie Lewis

For Tillie Lewis, relationships were everything—the escape route, the leg up, and the bridge to business ownership. And it’s not that Lewis herself described her opportunities this way. Like many successful people, she tended to tell a tale of individual initiative when asked about her entrepreneurial pathway, underestimating both the degree of luck in her success and the contributions of the many other people who helped to facilitate her good fortune. Robert H. Frank’s recent Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy reveals how common this tendency is even today and the ways in which it can be characterized as a psychological adaptation that ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1: Constructing Entrepreneurial Pathways

- 2: Government and Women’s Business Ownership

- 3: Labor-Management Relations

- 4: Gender as Brand Management

- 5: Asserting Self-Worth

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index