eBook - ePub

Persons of Color and Religious at the Same Time

The Oblate Sisters of Providence, 1828-1860

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Persons of Color and Religious at the Same Time

The Oblate Sisters of Providence, 1828-1860

About this book

Founded in Baltimore in 1828 by a French Sulpician priest and a mulatto Caribbean immigrant, the Oblate Sisters of Providence formed the first permanent African American Roman Catholic sisterhood in the United States. It still exists today. Exploring the antebellum history of this pioneering sisterhood, Diane Batts Morrow demonstrates the centrality of race in the Oblate experience.

By their very existence, the Oblate Sisters challenged prevailing social, political, and cultural attitudes on many levels. White society viewed women of color as lacking in moral standing and sexual virtue; at the same time, the sisters' vows of celibacy flew in the face of conventional female roles as wives and mothers. But the Oblate Sisters' religious commitment proved both liberating and empowering, says Morrow. They inculcated into their communal consciousness positive senses of themselves as black women and as women religious. Strengthened by their spiritual fervor, the sisters defied the inferior social status white society ascribed to them and the ambivalence the Catholic Church demonstrated toward them. They successfully persevered in dedicating themselves to spiritual practice in the Roman Catholic tradition and their mission to educate black children during the era of slavery.

By their very existence, the Oblate Sisters challenged prevailing social, political, and cultural attitudes on many levels. White society viewed women of color as lacking in moral standing and sexual virtue; at the same time, the sisters' vows of celibacy flew in the face of conventional female roles as wives and mothers. But the Oblate Sisters' religious commitment proved both liberating and empowering, says Morrow. They inculcated into their communal consciousness positive senses of themselves as black women and as women religious. Strengthened by their spiritual fervor, the sisters defied the inferior social status white society ascribed to them and the ambivalence the Catholic Church demonstrated toward them. They successfully persevered in dedicating themselves to spiritual practice in the Roman Catholic tradition and their mission to educate black children during the era of slavery.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Persons of Color and Religious at the Same Time by Diane Batts Morrow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Persons of Color and

Religious at the Same Time

THE CHARTER MEMBERS OF

THE OBLATE SISTERS

Persons of Color and

Religious at the Same Time

THE CHARTER MEMBERS OF

THE OBLATE SISTERS

Roman Catholic reference sources define the term “charism” as a spiritual gift, talent, or grace that God gives individuals to use for the spiritual welfare and benefit of the Christian community. These sources consider charisms manifestations of the Holy Spirit animating the church; as such, charisms constitute social graces in that they lead their recipients to the total service of Christ in the church. Church sources maintain that in every age the Holy Spirit has endowed saints, founders of religious orders and movements, and individuals from both the clergy and the laity with charisms to speak to their own age.1

Historically, founders of religious societies imprinted their respective communities with their personal charisms. The secular definition of the term “charism”—a special quality of leadership that captures the popular imagination and inspires unswerving loyalty—reflects this essential relationship between religious founders and their communities. This integral component of religious formation also occurred in the Oblate experience. Much of the life of Elizabeth Clarisse Lange, Oblate cofounder with James Joubert, remains undocumented prior to 1828. However, two salient characteristics of her pre-Oblate life prove verifiable: her fervent devotion to the Roman Catholic faith, noted by both her confessor and her cofounder, and her vocation to teach.2 The Oblate Sisters incorporated these personal qualities of Elizabeth Lange in their community identity.

The historical and sociocultural contexts in which sisterhoods formed also influenced their respective identities. As did all societies of women religious in the nineteenth-century United States, the Oblates contended with both the entrenched, male-centered orientation of the Roman Catholic Church and the encroachments of patriarchal tendencies in American society. In studying nineteenth-century women in general as well as the histories of communities of women religious operating within the concentric circles of male-dominated church and society, determining female agency frequently proves challenging. Standard histories customarily credit men with the foundation of women’s teaching communities. Indeed, for the first decade of Oblate existence, their Sulpician cofounder James Joubert personally maintained the Oblate annals, imposing a male perspective on the only extant account of the community’s history. Furthermore, two of the earliest histories of the community, written by Oblate Sisters, followed the annals closely and portrayed Joubert as the sole founder and Elizabeth Lange merely as a charter member and first superior of the community.3

But the Oblate Sisters formed one of four sisterhoods founded in the United States between 1809 and 1829 that evolved from previously existing associations of lay women teachers organized in response to perceived community needs. Reinterpreting James Joubert’s role as more that of a facilitator and less that of a micromanager of daily Oblate affairs restores focus on the original personal charisms of Elizabeth Lange and Marie Balas.4

The fact that Lange and Balas had independently established a school in Baltimore demonstrated their determination to address a perceived need for education in their new country without seeking white, male, or institutional approval to proceed. Circumstantial evidence suggests the Fells Point area in east Baltimore as the probable location of their home-based school. Lange and Balas had discussed with Reverend John Francis Moranvillé, pastor of St. Patrick Church in Fells Point, prospects for establishing a school for colored people at the Point, “the home of many French sea-captains engaged in trade with the West Indies, and they, with their families and slaves, made up the early congregation.”5

Oblate member and Superior Sister Mary Theresa Catherine Willigman, generally recognized as the first Oblate historian, recalled in her late-nineteenth-century accounts that black Caribbean émigré parents “lost no time in placing their children in Miss Lange’s school,” which was “filled with the children of the most intelligent families of Baltimore.” Significantly, Willigman continued, “However, let me add here that no distinction whatever was made among the pupils, and a very large number of the poorer class who had no means of paying for their tuition was admitted.”6 Lange’s school evidently served a broad spectrum of the black Francophone community, from poor families to those enjoying sufficiently comfortable circumstances to finance their children’s education at the school.7

Joubert’s own account of his first meeting with Elizabeth Lange and Marie Balas in 1828 clearly indicated his full appreciation of their teaching competence and their independent means. He further acknowledged that Lange and Balas revealed to him spontaneously and unsolicited their pre-existing religious vocations:

In consequence I imparted my plans on this subject to two excellent colored girls, well thought of and very capable of keeping this school. Both of them told me that for more than ten years they wished to consecrate themselves to God for this good work, waiting patiently that in His own infinite goodness He would show them a way of giving themselves to Him. . . . They promised to do everything that I should think of to further this work, and they put themselves and all that they had entirely at my disposal, which necessitated their discontinuing a small free school which they had been having for a number of years at their home.8

After Lange and Balas declared their religious vocations, Joubert asserted, “Up to this time I had been thinking of just founding a school.” Citing considerations of stability and efficiency, he concluded, “I thought of founding a kind of religious society. . . . Hence it was then that I conceived the idea of founding the Sisters of Providence. I declare before God that I had no other desire than to advance His glory.”9 Beneath the veneer of his exclusive assumption of the credit for the Oblate foundation, Joubert’s account suggests that he himself remained fully cognizant of the collaborative, mutually advantageous nature of the Oblate venture. Joubert acquired the services of experienced teachers while Lange and Balas gained official church sanction of their teaching endeavors and the realization of their religious vocations.

That these two black Catholic women persisted in their religious vocations for a decade prior to fulfillment reveals much about the personal charisms of two of the charter members of the Oblate Sisters of Providence. In common with the lives of founders of other religious communities, the lives of Lange and Balas embodied the charismatic model of the “grace of constant, lifelong fidelity to the living of the Christian life in one’s state in the Church, despite trials and difficulties of every type.”10 Unaided by external acknowledgment or official encouragement, Lange and Balas relied exclusively on their internalized commitments to their religious vocations based on their faith that God would provide.

Joubert himself may have sensed this wellspring of black Catholic female activism at the inception of the Oblate community. The Oblate Sisters of Providence adopted as a patron St. Frances of Rome, who in the fifteenth century had founded an oblate community of women religious engaged in charitable works in the world. The term “oblate” means “one offered” or “made over to God.”Throughout church history, oblate has referred variously to children dedicated to monasteries by their parents, to laymen and -women who did not take the vows binding religious but affiliated and worked with monks or nuns, and to several different societies and congregations of priests and nuns.11

St. Frances of Rome organized a group of Roman noblewomen already engaged in charitable hospital work into a religious community that received papal approval of their constitutions in 1433. She ranked among the first female founders of a church-sanctioned service sisterhood who both institutionalized a preexisting mission in the identity of her community and earned recognition as the exclusive founder of her community, without male collaboration.12 While apparently conforming to contemporary social conventions and expectations about white male dominance, Joubert nevertheless acknowledged black female initiative within southern U.S. society and the patriarchal Roman Catholic Church. Elizabeth Lange and Marie Balas had already committed themselves to religious vocations and engaged in the Oblate community’s defining mission: the education of children of color. The choice of St. Frances of Rome as an Oblate patron consequently reflected the seminal roles of these two women in the formation of the Oblate Sisters of Providence.

On 13 June 1828 San Domingan émigré Rosine Boegue joined Elizabeth Lange and Marie Balas to begin their novitiate, or period of spiritual preparation and training prior to professing the vows of a full member of a religious community. During this trial year the sisters collaborated with Joubert in the formulation of the Oblate Rule and Constitutions, the customized set of regulations guiding all facets of behavior for members of religious communities. That same day the School for Colored Girls opened with eleven boarding and nine day students. A rented residence at 5 St. Mary’s Court, in close proximity to St. Mary’s Seminary and Lower Chapel, served as both Oblate convent and school that first year.

A year later, on 2 July 1829, in their second rented residence at 610 George Street, James Joubert received the professions of the four charter members of the Oblate Sisters of Providence. The fourth candidate, Almaide Duchemin, although born in Baltimore, claimed San Domingan ancestry through her mother, Betsy Maxis Duchemin. Elizabeth Lange became Sister Mary Elizabeth; Marie Balas, Sister Mary Frances; Rosine Boegue, Sister Mary Rose; and Almaide Duchemin, Sister Mary Therese.13

No extant record reveals the self-perceptions or understandings of Elizabeth Lange, Marie Balas, Rosine Boegue, and Almaide Duchemin about their own roles in the founding of the Oblate Sisters of Providence. But the racial prejudice prevalent in American church and society precluded “their taking the direct and public initiative to start an order of black religious women.”14 The Roman Catholic Church required all communities of women religious to function under the spiritual directorship of a priest. For the black Oblate Sisters, considerations of race compounded their gender status, doubly requiring the intervention and sponsorship of the white Sulpician priest James Joubert to validate their existence as constituencies in both the Roman Catholic Church and antebellum American society.

In fulfilling their missions, founders of nineteenth-century American sisterhoods established schools, hospitals, or orphanages. These institutions had such obvious social utility that the general public patronized and recognized them as both serving a public need and consonant with social values. However, unlike founders of white communities serving white society, Elizabeth Lange and James Joubert proposed to provide for the despised black population both a corps of teachers from its own ranks and an education, neither of which the general public considered serving a public need or consonant with prevailing social values. Indeed, some segments of American society objected to education for free black people as much as for slaves.15 The Oblate Sisters’ very existence as free women of color organized into a religious community to educate black children challenged prevailing social and episcopal attitudes about race and gender. If not revolutionary, Lange’s and Joubert’s foundation of the Oblate Sisters constituted a heroic feat.

THE DEARTH OF extant evidence frustrates efforts to reconstruct the pre-Oblate lives of the charter members of the Oblate community in detail. Nevertheless, sufficient evidence survives to document a broad outline of some of their personal histories. Born of racially mixed parentage probably in the 1780s in either Saint Domingue or Cuba,16 Elizabeth Clarisse Lange apparently enjoyed a relatively privileged life, including a formal education. The Sisters of Notre Dame du Cap-Français had established an academy for girls in Le Cap, St. Domingue, in 1733. The sisters had intended to educate young girls of both races originally, but the white colonists objected so strenuously to the prospect of racial integration that the sisters acquiesced to their demands that even catechetical instruction occur only on a segregated basis. However, in 1774 the English fleet lay siege to the city and Mother de Columbas, superior of the Sisters of Notre Dame du Cap-Français in that mission, vowed to institute special classes for mulatto and black girls if Le Cap escaped destruction. According to the Notre Dame du Cap-Français annals, a fierce storm arose and destroyed the English fleet in the harbor. Mother de Columbas fulfilled her vow, and from 1774 the sisters’ school accepted mulatto and black pupils as well.17 Elizabeth Lange and other early Oblate members of Caribbean origin may have enrolled in this convent school. Such an educational experience would have exposed these young girls of color to the religious life as an appropriate and viable vocation.

Lange emigrated with her mother to the United States, where she may have resided briefly in Charleston, South Carolina, and Norfolk, Virginia. Only the friendly intervention of certain ship captains who were indebted to Lange’s mother enabled the two émigrés to circumvent Charleston’s restrictions on the admission of colored people. Elizabeth Lange resided in Baltimore from at least 1813.18 Financial support from her father’s estate allowed Lange to maintain her independence in the slave city of Baltimore. The Oblate Sisters of Providence did not own slaves. But Elizabeth Lange, and later the Oblate community through her inheritance, clearly benefited from the institution of slavery, which generated planter wealth. Oblate accounts note that “Sister Mary [Lange] especially was very often the recipient of large sums of money, sent from her home in Santiago” and that Lange had inherited “$2000 left her by Monsieur Lange her father” and had “received in settlement $1411.59 which was due her” in 1832 and 1833, respectively.19 Like James Joubert, Elizabeth Lange probably maintained more direct connections with slave society than acknowledged in previous accounts. Unlike Joubert, Lange became an anomaly in her adopted home of Baltimore. Elizabeth Lange was a genuine victim of the slave insurrection so constantly feared yet seldom realized in U.S. slave society. But as a free woman of color, she elicited little sympathy from southern slaveholders or other white people who noted her “of color” designation more assiduously than either her planter connections or her free status.

The appearance of the names of Elizabeth Clarisse Lange and Marie Magdelaine Balas on the registers of three religious confraternities or devotional societies proves instructive. Within the universal Roman Church, religious confraternities were literally catholic in their membership, encompassing laity, clergy, and religious, male and female, rich and poor, young and old alike. Each confraternity selected one act, such as reciting a specific prayer, wearing a certain medal, or regular assistance at Mass as its distinguishing feature or bond of association. Such groups might also hold regular, exclusive meetings or weekly rites, thus fostering a sense of bonding and cohesion.20

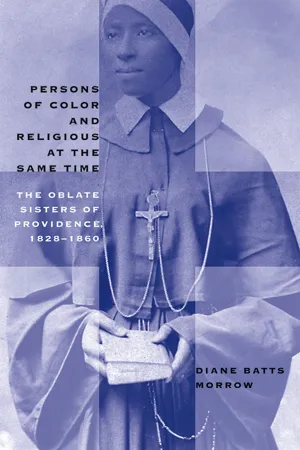

Sister Mary Elizabeth Lange, O.S.P., Oblate cofounder and first superior, photographed in her later years (Courtesy of Archives of the Oblate Sisters of Providence, Baltimore, Md.)

Entries in the registers of three religious confraternities cite the names Elizabeth Clarisse Lange and Marie Magdelaine Balas adjacent to each other. This consistent pairing of their names in the registers documented their close pre-Oblate collaboration. Early in his association with these tw...

Table of contents

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- CHAPTER ONE - Persons of Color and Religious at the Same Time: The Charter Members of the Oblate Sisters

- CHAPTER TWO - James Hector Joubert’s a Kind of Religious Society

- CHAPTER THREE - The Respect Which Is Due to the State We Have Embraced: The Development of Oblate Community Life and Group Identity

- CHAPTER FOUR - Our Convent: The Oblate Sisters and the Baltimore Black Community

- CHAPTER FIVE - The Coloured Oblates (Mr. Joubert’s): The Oblate Sisters and the Institutional Church

- CHAPTER SIX - The Coloured Sisters: The Oblate Sisters and the Baltimore White Community

- CHAPTER SEVEN - Everything Seemed to Be Progressing: The Oblate Sisters and the End of an Era, 1840–1843

- CHAPTER EIGHT - Of the Sorrow and Deep Distress of the Sisters . . . We Draw a Veil: The Oblate Sisters in the Crucible, 1844–1847

- CHAPTER NINE - Happy Daughters of Divine Providence: The Maturation of the Oblate Community, 1847–1860

- CHAPTER TEN - Our Beloved Church: The Oblate Sisters and the Black Community, 1847–1860

- CHAPTER ELEVEN - The Oblates Do Well Here, Although I Presume Their Acquirements Are Limited: The Oblate Sisters and the White Community, 1847–1860

- Conclusion

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography