eBook - ePub

St. Francis of America

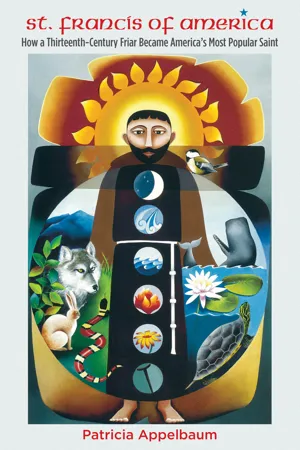

How a Thirteenth-Century Friar Became America's Most Popular Saint

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

St. Francis of America

How a Thirteenth-Century Friar Became America's Most Popular Saint

About this book

How did a thirteenth-century Italian friar become one of the best-loved saints in America? Around the nation today, St. Francis of Assisi is embraced as the patron saint of animals, beneficently presiding over hundreds of Blessing of the Animals services on October 4, St. Francis’s Catholic feast day. Not only Catholics, however, but Protestants and other Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, Jews, and nonreligious Americans commonly name him as one of their favorite spiritual figures. Drawing on a dazzling array of art, music, drama, film, hymns, and prayers, Patricia Appelbaum explains what happened to make St. Francis so familiar and meaningful to so many Americans.

Appelbaum traces popular depictions and interpretations of St. Francis from the time when non-Catholic Americans “discovered” him in the nineteenth century to the present. From poet to activist, 1960s hippie to twenty-first-century messenger to Islam, St. Francis has been envisioned in ways that might have surprised the saint himself. Exploring how each vision of St. Francis has been shaped by its own era, Appelbaum reveals how St. Francis has played a sometimes countercultural but always aspirational role in American culture. St. Francis’s American story also displays the zest with which Americans borrow, lend, and share elements of their religious lives in everyday practice.

Appelbaum traces popular depictions and interpretations of St. Francis from the time when non-Catholic Americans “discovered” him in the nineteenth century to the present. From poet to activist, 1960s hippie to twenty-first-century messenger to Islam, St. Francis has been envisioned in ways that might have surprised the saint himself. Exploring how each vision of St. Francis has been shaped by its own era, Appelbaum reveals how St. Francis has played a sometimes countercultural but always aspirational role in American culture. St. Francis’s American story also displays the zest with which Americans borrow, lend, and share elements of their religious lives in everyday practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access St. Francis of America by Patricia Appelbaum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teologia e religione & Denominazioni cristiane. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One: The Nineteenth Century

A Protestant Catholic and Catholic Protestants

An English-speaking Protestant of the mid-nineteenth century, preparing to explore continental Europe for the first time, might have picked up Octavian Blewitt’s 1850 guidebook to central Italy. Along with its descriptions of Rome, Florence, and Ravenna, the book noted that “Assisi is the sanctuary of early Italian art.” A similar book in 1905, however, declared, “Assisi is the city of St. Francis.” In the space of some fifty years, St. Francis of Assisi went from an insignificant, almost unknown figure to a universally familiar one. How did this transformation take place? Why was St. Francis the center of a description of Assisi in 1905, but not in 1850?1

This chapter shows how American non-Catholics gradually grew acquainted with the figure of St. Francis during the second half of the nineteenth century. As we shall see, many events and cultural forces contributed to the process. First of all, Protestants were beginning to realize that the history of Christianity before the Reformation was also their own history. At the same time, travel to Europe was becoming more accessible, which meant more exposure to European art and architecture, including many images of saints. American Protestants were also encountering Catholics more often at home. All of this, along with broader cultural currents, led to a reassessment of their relationship with Catholic traditions in general and saints in particular.

Other saints also caught Protestants’ interest, but none became as popular as Francis. He was attractive for many reasons—not least the fact that there was a reasonable amount of historical evidence for his life. It was clear that he had actually lived, and in a particular place, at a particular time. But not all readers interpreted the evidence the same way, and it is incomplete in any case. Thus a number of different images of Francis emerged during the nineteenth century, emphasizing different features of Francis and meeting different needs. Francis was a subject for imaginative elaboration, personal relationship, and collective appropriation. All of these images, however, grew out of the culture and concerns of the nineteenth century. And instead of affirming cultural standards, most of them proposed alternatives.

A chronological outline gives us a good overview of the way Francis became familiar to non-Catholics. A body of literature about Francis written by non-Catholics built up slowly from the 1840s until about 1870. Around that year the pace of publication increased. Events in 1870—the first Vatican Council and the final unification of Italy—drew international attention to Italy. More broadly, the last quarter of the nineteenth century was a time of growing prosperity and also of an emerging cultural critique. Both of these forces contributed, in different ways, to the increasing interest in Francis. The seven-hundredth anniversary of Francis’s birth, in 1881–82, prompted a new outpouring of scholarly literature and popular works. Thus by 1888 it was possible for a book reviewer to say, “The story of St. Francis has been fully and frequently related.” And in 1893, a new biography shaped perceptions of Francis for the twentieth century. The process was not uniform—some writers in the 1880s and 1890s still had to explain who Francis was and why Protestants should be interested in him—but this was the general trajectory.

Cultural Currents

The Protestant rediscovery of Francis began in the context of an ambivalent Protestant encounter with Catholicism. In the United States, this encounter began in the late eighteenth century, but gained force after 1830, with increased immigration from Catholic countries, the annexation of the Southwest, and the gradual growth of overseas travel. The literary historian Jenny Franchot argued in a classic work that Protestants reacted with both approach and avoidance, attraction and repulsion. Since the Reformation of the sixteenth century, Protestantism had generally regarded Roman Catholicism as a threatening “other.” In nineteenth-century America, anti-Catholicism was common and sometimes violent.2

But many non-Catholics responded to the encounter with curiosity, appreciation, and selective appropriation. Travel and genteel education exposed them to the surprising attractions of pre-Reformation art and architecture. Midcentury travel literature dwelt on Catholic peasant and urban life as well. Some writers of fiction—notably Nathaniel Hawthorne and Harriet Beecher Stowe, descendants of New England Puritans—explored such Catholic themes as confession and intercession. There were a few prominent public conversions to Catholicism and a small but steady stream of less visible ones.

There were many dimensions to Protestants’ ambivalence. First, Catholic power attracted and puzzled them. They could not quite account for the Roman church’s survival “after [its] having been directed offstage nearly four centuries earlier.” Saints also proved puzzling. Franchot argues that Protestant writers came to terms with them by framing them as heroic individuals acting in spite of, or even against, the church—not as holy or divinely gifted persons. As we shall see, this tendency continued well into the twentieth century and was surely a way of thinking about Francis. Catholic worship posed yet another problem. The Anglican churches struggled for years over the Oxford Movement, which among other things encouraged the revival of pre-Reformation practices. At the same time, many American Protestants developed a “deeply mixed fascination for Roman Catholic worship.” As historian Ryan Smith has observed, Gothic buildings, visual symbolism such as crosses, and liturgical practices such as processions were derided as “popery” in the 1830s, but were common in mainstream Protestantism—including its Anglican branch—by the 1890s.3

A related phenomenon was the medievalist movement, which was well established in Britain by 1850, reached its height in the United States after the Civil War, and remained influential long after that time. Medievalism was not only an artistic movement but a far-reaching cultural one. Against the dominant ideology of progress and the growing industrial economy, medievalism appealed to a desire for simplicity, self-reliance, and closeness to nature. These qualities were thought to foster a more deeply grounded local and national identity. Proponents regarded the Middle Ages as a time of almost childlike innocence, fresher and purer than the jaded nineteenth century. Gothic architecture shared in the ideal of purity because it followed forms found in nature. More significantly, it relied on human craft, in contrast to the anonymous production of the industrial model.

Both medievalism and the encounter with Catholicism contributed to a late-century cultural phenomenon known as antimodernism. Historian T. J. Jackson Lears has described the complex mental world of educated Victorians who reacted against the alienation and impersonality of modernity, especially in the years between 1880 and 1920. For these antimodernists, the Middle Ages represented authentic experience and cultural unity. Peasants, saints, and mystics embodied innocence, simplicity (both material and spiritual), faith, imagination, vitality, nature, access to sacred mystery, and “primal irrationality,” together with, paradoxically, moral strength and self-control. In this reading Francis epitomized the medieval ideal for late-century antimodernists.4

Protestantism struggled with modernity in another dimension as well. The nineteenth century brought stunning challenges to traditional belief—most significantly the rising authority of science, the theory of evolution, and the historical criticism of the Bible. At the same time, a popular theology of consistent, all-forgiving love began to displace the long tradition of self-scrutiny and conviction of sin that was rooted in American Calvinism. One consequence of these shifts was a reconsideration of the idea of Jesus. Historical criticism generated interest in the historical Jesus—questions about what was really “true” about him. At the same time, it intensified questions about the truth of miraculous and supernatural claims. On the other hand, many liberals, “seekers,” and dissenters distinguished between Jesus himself and church teachings about him, retaining a sense of personal relationship to Jesus even when they drifted away from formal ecclesial structures. The result was a widespread emphasis on the human Jesus, his teachings, and his love.5

A final factor was the ideology of nature. Idealization of the natural world was a long and complex cultural tradition, but in the later nineteenth century it functioned especially as an outlet for disaffection with urban and industrial growth and as a way of resisting religious authority. It drew not only on the long Romantic tradition but on the particular expression of that tradition in New England transcendentalism and, later in the century, on nostalgia for the vanishing wilderness.6 Francis’s close association with nature was a far less prominent theme in the nineteenth century than it is in the twenty-first, but it was a persistent undercurrent. Distinctive among saints, this connection with nature undoubtedly resonated with nineteenth-century sensibilities, even among those who resisted formal religious ties.

Within these contexts I want to look more closely at the process by which American non-Catholics came to know about Francis and affirmed his legitimacy, and at the images of Francis they constructed. Much of this process drew on European sources, as we shall see.

Protestants, Francis, and History

From Martin Luther onward, most Protestants thought that religious orders were unnecessary at best and ungodly at worst. Franciscan friars were widely regarded as lazy, greedy, and corrupt. But Protestant thinking about Francis and his followers began to change in the mid-nineteenth century.7

One of the earliest sources of this altered thinking was Protestant historicism. “Church history” as a modern academic discipline began to emerge during the first half of the nineteenth century. As it developed, Protestants gradually, and not without controversy, came to realize that the history of the pre-Reformation church pertained also to them. Thus the earliest non-Catholic works on Francis—and many later ones as well—present themselves in the first instance as historical projects.8

Perhaps the most important of these works, especially for the general public, was an essay by Sir James Stephen. Stephen was a British government official, an evangelical Anglican, and, at that time, an avocational historian. His essay, published in 1847, was itself a review of two French biographies and made reference to an unfinished “History of the Monastic Orders” by the poet Robert Southey. The essay appeared in periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic and was reprinted in an 1849 collection.9

Stephen first had to argue that it was all right to study monastic orders—that they were “legitimate object[s] of ecclesiastical history.” By “monastic,” he meant all religious orders, although Franciscans were technically not monastics but mendicants. Like any good historian, Stephen discussed the sources on Francis, noting that they were “more than usually copious and authentic.” And he looked for the causes of historical events in human sources rather than in supernatural ones. In this context he recounted and reflected on the story of the saint’s life.10

Stephen was not alone in his work. At least three general histories of the church or of monasticism were published between 1855 and 1861. Charles Forbes de Montalembert’s Monks of the West, from St. Benedict to St. Bernard began publication in Paris in 1860 and appeared in English translation in both Boston and Edinburgh within a year. General ecclesiastical histories, such as Henry Hart Milman’s, also included biographies of saints. And in 1856, the German historian Karl von Hase published a life of St. Francis frequently cited by Anglophone writers. Thus scholars and educated readers encountered Francis through the study of history.11

Protestants found much with which to identify. Stephen, for example, argued that the Franciscan order survived its founder’s death because it was a forerunner of the Reformation. Unlike the Benedictines and other settled monastic orders, he said, the mendicant Franciscans restored religious purity, engaged with the world, and sided with the weak and humble. Above all, they fostered “the Mission and the Pulpit”—a Protestant trope that was still being repeated as late as 1886. The historian C. K. Adams wrote in 1870 that Francis’s purpose was “the work of a Reformation in the church” in the period when “the human intellect [sought] to rise up against the Roman yoke and throw it off.” His Baptist colleague Samuel L. Caldwell added, “There is a lesson, too, of the power there is in preaching.” Later authors suggested that Franciscans were the Puritans or Methodists of their day; one source in 1884 went so far as to compare Francis with the popular evangelist Dwight Moody. This proto-Protestant image of Francis, then, provided both a point of connection and a sense of reassurance for Protestants ambivalent about Catholicism.12

The image did not go unchallenged, however. The Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature (1870), whose editorial committee was a veritable Who’s Who of evangelical American Protestant scholars, was sharply critical of most claims about Francis. The Cyclopædia cited the documentary sources on the saint, but found in them evidence of an unstable and immoral figure. Francis “imagin[ed]” he heard a call from heaven and “pretended” to perform miracles. The pope’s approval of the order, said the writer, was the cynical use of a madman for the pope’s own purposes and also served Francis’s “ambition.” As for Francis’s moral character, the author comments, “Romish casuists say that [Francis’s sale of his father’s goods] was justified by the simplicity of his heart. It is clear that his religious training had not instructed him in the ten commandments.” Nevertheless, the Cyclopædia mentioned the stories about birds with a touch of sentimentality, even while condemning the potential for pantheism. And it made an entirely favorable judgment of Francis’s emphasis on love.13

Even among more sympathetic readers, the contested areas of Francis’s story were those that were most distant from Protestantism. These readers struggled with his relationship to Catholic institutions, his obedience to the pope, the power structures of the Franciscan order, corruption within the order, and the meaning of the divine command to “rebuild my church.” They were concerned about Francis’s apparent disregard for ordinary morality. They were also uneasy about his treatment of his body, starved and deprived in ascetic discipline and finally mutilated by the stigmata. Difficult as these issues were, however, non-Catholic thinkers did not ignore them, but thought and argued about them. In the end most followed Stephen, consciously o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- St. Francis of America How a Thirteenth-Century Friar Became America’s Most Popular Saint

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One: The Nineteenth Century

- Chapter Two: The Early 1900s

- Chapter Three: Between the Wars

- Chapter Four: Hymn, Prayer, and Garden

- Chapter Five: Postwar Prosperity

- Chapter Six: The Hippie Saint

- Chapter Seven: Blessing the Animals

- Chapter Eight: Living Voices

- Chapter Nine: Into the Future

- Epilogue

- Appendix: Survey

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of Names

- Index of Subjects