- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In 1860, Somerset Place was one of the most successful plantations in North Carolina — and its owner one of the largest slaveholders in the state. More than 300 slaves worked the plantation’s fields at the height of its prosperity; but nearly 125 years later, the only remembrance of their lives at Somerset, now a state historic site, was a lonely wooden sign marked “Site of Slave Quarters.”

Somerset Homecoming, first published in 1989, is the story of one woman’s unflagging efforts to recover the history of her ancestors, slaves who had lived and worked at Somerset Place. Traveling down winding southern roads, through county courthouses and state archives, and onto the front porches of people willing to share tales handed down through generations, Dorothy Spruill Redford spent ten years tracing the lives of Somerset’s slaves and their descendants. Her endeavors culminated in the joyous, nationally publicized homecoming she organized that brought together more than 2,000 descendants of the plantation’s slaves and owners and marked the beginning of a campaign to turn Somerset Place into a remarkable resource for learning about the history of both African Americans and whites in the region.

Somerset Homecoming, first published in 1989, is the story of one woman’s unflagging efforts to recover the history of her ancestors, slaves who had lived and worked at Somerset Place. Traveling down winding southern roads, through county courthouses and state archives, and onto the front porches of people willing to share tales handed down through generations, Dorothy Spruill Redford spent ten years tracing the lives of Somerset’s slaves and their descendants. Her endeavors culminated in the joyous, nationally publicized homecoming she organized that brought together more than 2,000 descendants of the plantation’s slaves and owners and marked the beginning of a campaign to turn Somerset Place into a remarkable resource for learning about the history of both African Americans and whites in the region.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Somerset Homecoming by Dorothy Spruill Redford,Michael D'Orso in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Voices from the Past

They are dead now, all of them. The Collinses, the Pettigrews, and their slaves. Nineteenth-century ghosts. But even now, they are still apart, white and black, as separated in death as they were when they were living.

The whites left snapshots of their lives behind. In letters and ledger books they told me who they were and how they lived. I knew what the Collinses ate, how they dressed, where they slept, how they spoke. They spoke on paper, and their voices can still be heard a century after their bodies were put in the ground. There is little that is magical about lives like that, little to imagine, little room for mystery when the mundane is so specifically preserved.

The black people whose names I held in my hand left nothing. What they wrote, neither they nor their owners kept. And when they spoke, really spoke, it was only to one another. The voices their owners heard were not the voices they shared among themselves. When they died, their real voices went with them. And the echoes that were left became mystery, then more. The mystery became magic. It’s that way with the dead—the less we know about the lives they led, the more we make them myths when they are gone. We fill the void with our own imagining, with our own hopes.

That is what I had done as I worked my way to Somerset. Because of the very fact that all I had were lists of slave names and dates culled from courthouse records and company account books, I wrapped each of those names in an aura of wonder, of richness. Once I arrived at the place where they lived, I realized there was the chance I would be robbing that richness by digging into the reality of their pasts. In a way I was intruding, peeling away their mystery by reaching for the concrete, the three-dimensional. In a way it seemed right to leave my ancestors among the mists of myth, to keep them apart from the Collinses—to allow them in death to be more than the people who owned them in life.

But that would be to deny their own very real lives, to put my dreams above theirs. I was here now, at Somerset. I had the names. I had the place. I had to go on, to piece together their existence—as individuals; as a group.

There were no straightforward, firsthand accounts of slave life at Somerset. Only references among the Collinses’ and Pettigrews’ correspondence. Costs of slaves in old ledger books. Entries of money paid for slave shoes and buttons.

Tiny slivers of reality, mere shavings of the past, disjunctive fragments of time.

Mention of a persistent runaway in an overseer’s letter. Plantation inventories listing slaves by cabin, telling me who lived with whom, giving me a sense of families, but only a sense. An archaeologist’s reconstruction describing where those cabins stood, how they were built, even their color—white.

I walked into a church where my ancestors had sung both before and after they were told they were free. There were records in that church’s registry—more names, more dates of births, of marriages, of deaths. I pushed through brambles and sank in mud, hunting for family cemeteries in the woods beyond the plantation, where the emancipated slaves who moved off Somerset after the war buried their dead and where I found gravestones that gave me more names, always more names.

I studied books and historical articles on the African slave trade, on slave life on other plantations in other states, on runaway slaves in eighteenth-century North Carolina, even on naming patterns among slaves and owners in the antebellum South. I read interviews with former North Carolina slaves collected by the federal government during the 1930s, accounts that included one precious conversation with a former Somerset slave.

As these scattered splinters of the past piled before me, images took shape. Some of the pieces were linked without question. Others required logic and deduction to join them together. Sometimes I had no choice but to guess my way from one to another. The lives I resurrected were shaped by facts, but they remained ghostly—cryptic outlines shimmering with the dignity of vagueness.

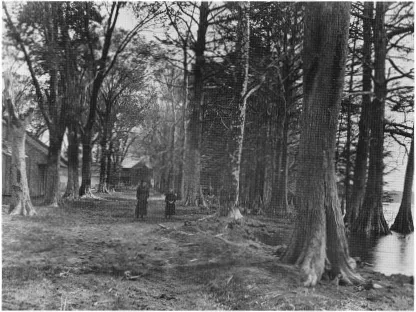

Slave cabins and the rear of the mansion at Somerset Place, ca. 1900–1915. (N.C. Department of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History)

The Africans were the vaguest.

All I knew of the Camden’s journey was that the eighty-ton brig was sent north in the winter of 1784 with a hold full of tobacco, pork, beef, rice, and molasses and came back to Edenton a year and a half later carrying eighty Africans. In between—probably during the “fitting out” in Boston—I was sure the brig’s hold was loaded with a healthy supply of New England rum. When American ships shopped for African slaves in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, rum was the going currency. Anyone who ever took a high school history class knows about the triangular slave trade system: rum for slaves for molasses for rum. But now I was seeing it in human, not historical terms. These were my relatives being bartered for liquor. So when I read a passage like this one from a book called Black Cargos: A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade, the idea was more than academic:

[A]t the home port the vessel would take on a cargo chiefly or entirely of rum. In Africa it was exchanged for as many slaves as it would buy. On the return trip slaves were sold in the West Indies and a part of its proceeds would be invested in molasses, usually in French or Spanish Islands where it was cheaper. On the final leg of the voyage, the vessel would carry the molasses back to New England to be distilled to make more rum, to buy more slaves.

Such efficiency. But the Camden’s journey was different. First, the standard slaving vessel was crammed with as many bodies as it could carry. “Tight packing,” they called it, and the traders counted on losing an average of 30 percent of their slaves during the voyage—to heat, disease and, often, suicide. Three out of ten human beings were written off like so many spoiled vegetables. A hundred-ton ship typically carried two hundred and fifty slaves, most of whom were unclothed, sleeping in their own excrement and crying for help in languages their captors had no reason to understand.

The Camden’s load of eighty was a light one—“loose packed.” And the fact that a grist mill was installed on board to grind fresh meal to feed the Africans indicates that Collins and his partners wanted healthy bodies to step off that ship. Their canal was a special project, and these men were taking care of the human machinery—the skilled labor they’d sought in Africa—that would dig it. There was no humanity in their kindness—it was just good business. They weren’t pampering their cargo—the Lake Company account books listed “handcuffs and fetters” bought for the Camden.

I had no way of knowing exactly where the Camden loaded its slaves. I could find no records of the ship’s African destination. But the history books I studied told me the western Gold Coast—where tribes such as the Ashanti, Bono, Brong, and Fante had moved during the seventeenth century, and where European colonists had set up trading posts earlier than that—was the center of African slave trade when the Camden sailed there in 1785. If the brig did dock there, the natives it picked up would have shared a common language—Akan—and a common culture. Indeed, after talking with a professor of African studies I met through a friend from my church in Norfolk, I learned that the African-sounding names I had found among the company’s 1803 inventory included anglicized versions of Akan names: “Quaminy” for the Akan “Kwame”; “Donkey” for “Donko”; “Cuff” for “Kofi.”

There was another reason the Camden would have wanted West African slaves: rice. The Lake Company needed bodies that could resist the malaria that festered in the swamps where the canal was to be dug and in the wet fields where the rice would be grown. Not only were West Africans skilled rice planters who had grown the crop on the Windward Coast for centuries, but they were known to have a relative resistance to malaria, an immunity we now know is linked to the sickle-shaped blood cells of black people from tropical climates. But Ebenezer Pettigrew didn’t know anything about sickle cells when he wrote a letter commenting on the African slave labor. All he knew was the necessity for ditch-diggers, a need he described in a blunt letter:

Negroes are a troublesome property, and unless well managed, an expensive one, but they are indispensable in this unhealthy and laborious country, for these long canals that are all important in rendering our swamplands valuable must be dug by them or not at all.

The canals were dug by what the Lake Company account book called “the new negros.” And even with their “immunity,” they fell sick. “Ague,” “flux,” and “bilious fever”—each a different way of describing malaria—were rampant. If the sickness was treated at all, the treatment was quinine, a poison that usually made the patient violently ill. Survive the cure, they said, and you’d have little problem with the disease. Samuel Dickinson was a doctor, and according to the Lake Company’s account books, his obligations included treating the medical needs of the slaves. Each month’s ledger book entry for “medicine for Negroes” was mostly for quinine.

But worse than the Africans’ hideous voyage to America or the disease-ridden swamps they were herded into once they got here was the emotional shock of being ripped from their tradition-soaked homeland and the unspeakable anguish of ending up in a completely unrecognizable land. According to a company overseer at the canal site, some of those first eighty Africans were actually driven into Lake Phelps by their grief:

At night they would begin to sing their native songs… . In a short while they would become so wrought up that, utterly oblivious to the danger involved, they would grasp their bundles of personal effects, swing them on their shoulders, and setting their faces towards Africa, would march down into the water singing as they marched till recalled to their senses only by the drowning of some of the party.

It wasn’t long before Collins ordered the singing stopped. Losing slaves to the lake was not cost-efficient.

Still, the Africans held on to what they could of their culture. An archaeology team from Duke University studied the Somerset site in 1982 and discovered pieces of “crude” pottery. In an article entitled “Digging up Slave History,” the team leader—a Duke history professor named Peter Wood—noted that simple, unglazed pottery had been found at eighteenth-century colonial sites for years and had always been assumed to be Indian. But this stoneware, he concluded, was “definitely Afro-American pottery.” So, he guessed, were many of the shards that had been found at other southeast Atlantic sites and assumed to be Indian.

“Archaeologists have been excavating these fragments for years without understanding them,” wrote Wood. “They were wearing cultural blinders that prevented them from recognizing evidence that was right in front of them.”

The message is obvious: Even scientists can be racists. Well intentioned, maybe. Unaware of their biases, hopefully. But racists nonetheless.

By recognizing the Somerset evidence for what it was, it was easy for Wood to give the clay fragments a simple, obvious explanation, one that escaped his colleagues at similar sites: “Perhaps they were made by men who had watched women create pottery in Africa and who were now obliged to make bowls on their own.”

Men without women. This was another adjustment my African ancestors had to make. The Camden’s cargo was almost all men. Women and children were not needed to dig a canal. These men left behind their African families and were forced to form new ones in North Carolina—yet another adjustment, since they shared neither the language nor the culture of American-reared slaves.

View of Somerset Place from Lake Phelps, ca. 1936. (N.C. Department of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History)

The early account books I found were filled with records of Collins and his partners “hiring out” their own personal slaves to the Lake Company, sending these American-born slaves from Edenton to the Somerset site. While the Africans dug, these “company slaves” built roads and cabins. By 1790 there were five slave houses standing along the shore of the lake. By that year thirty-three of the company’s Edenton-based slaves had joined the Africans in the swamp. And that was the year Guinea Jack and Fanny Collins were married.

Guinea Jack was one of the eighty Africans loaded on the Camden. He was among the oldest of the Somerset slaves still living when Josiah Collins III took over the plantation and began keeping extensive records of his human property. Guinea Jack was eighteen when he arrived at Lake Phelps. And he was still alive fifty-three years later, when his name appeared on an 1839 Collins slave inventory next to that of his African born wife of forty-nine years, Fanny. She and her husband survived the early years and had six children, only two of whom were still living in 1839. I also know Guinea Jack clung to at least one of his African customs—at the same time he was married to Fanny, he had another wife named Grace, who bore him one son. Although the practice faded as later generations of Somerset-born slaves replaced the original Africans, polygamy was not uncommon in the plantation’s early years.

I didn’t know how Guinea Jack lived, what his job was once the canal was finished, how he blended his African culture and language with those of the English-speaking slaves he met at Somerset. The picture of daily life on the plantation before Josiah III arrived in 1830 is a sketchy one. But just scanning the lines from the account books gave me telling glimpses into the early years. In 1787—a year after the Africans arrived and the same year the U.S. Constitution was signed—the following entries were among dozens recorded in the Lake Company logbooks:

April 19—Nine pounds to

Nathaniel Allen “for 3 days hire of Caesar.”

Nathaniel Allen “for 3 days hire of Caesar.”

May 22—Three pounds. “paid Caleb Benbridge for apprehending Negro Sam.”

May 24—One shilling to Josiah Collins “for Beef & Bread for Negroes.”

May 26—Two pounds, nine shillings to Samuel Dickinson “for sundry medicines for Negroes this month.”

May 26—Six shillings to Ebenezer Spruill “for bringing home runaway Negroe.”

June 11—Four pounds, six shillings “paid Wilkins for apprehending Negro Sam.”

June 27—Eight shillings “for 4 qts. Rum for Negroes.”

July 1—Four pounds “paid Joseph Oliver for building two Negroe houses.”

July 10—Twenty pounds, fourteen shillings “for 138 yds. Osnaburg for Negroes clothes.”

July 10—Two pounds “pd. James Ambrose for taking up two Negroes.”

August 21—Seventeen pounds, fifteen shillings “paid for making 60 shirts, 43 shifts, 60 pr. trousers & 33 coats.”

December 4—Two pounds, sixteen shillings “paid John Alexander for hogs stolen by our Negroes.”

December 4—Four pounds “paid John Porter for taking up Smart & Sambo.”

As the canal was being dug, Collins and his partners were buying clothing, building housing, even supplying rum for their slaves’ medicinal needs. All the necessities, as Collins probably saw it.

But still there were runaways.

It didn’t make sense for Collins to beat or whip the slaves who ran—he needed able bodies. If slaves like Sambo (who was also called Sam) or Smart insisted on slipping into the swamps every chance they got, Collins didn’t waste time with discipline. He simply sold them. An account book entry for April of 1789 listed Smart and Sam running away yet again. But this time, there was another entry in the same month, for the “net sale of sugar received for the Negro Smart, sold in the West Indies.”

In the end, sugar was worth more to the company than Smart. And there was a particular, brutal sting to his punishment—it would have been one thing to sell Smart to another plantation, but to dump him in the West Indies was, for the family he left behind, like sending him to the other side of the world. They could not even hope to ever see or hear of him again.

Another chronic runaway was Yellowman Dave Hortin, one of Ebenezer Pettigrew’s slaves. By 1820, Hortin and another Pettigrew slave named Pompey had earned a reputation for several escape attempts. Each time they left, it took nothing more than an ad in the local newspaper and they were found and returned. So Pettigrew probably expected a quick response from the following notice, printed in a September 1820 issue of the Edenton Gazette:

50 DOLLARS REWARD

My negro Pomp and Dave having run away I will give the above reward to any one who will deliver them to me or half the sum for the delivery of either one.

But this time the pair stayed at large for more than a year before they were spotted several counties away by a man who threatened to “kill them on the spot.” That’s how the man described his warning in a letter to Pettigrew:

Their reply was we cannot drop our guns but if you will not kill us we will lower the muzzles and come to you if you will give your word you will not kill nor try...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Somerset Homecoming

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Beginnings

- ‘Over de River’

- The Road Home

- The Arrival

- Voices from the Past

- Connecting

- Somerset Homecoming

- Epilogue

- Sources