- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

William L. Shea offers a gripping narrative of the events surrounding fighting at Prairie Grove, Arkansas, one of the great unsung battles of the Civil War, which effectively ended Confederate offensive operations west of the Mississippi River. Fields of Blood provides a colorful account of a grueling campaign that lasted five months and covered hundreds of miles of rugged Ozark terrain. In a fascinating analysis of the personal, geographical, and strategic elements that led to the fateful clash in northwest Arkansas, Shea describes a campaign notable for rapid marching, bold movements, hard fighting, and the most remarkable raid of the Civil War.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fields of Blood by William L. Shea in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Amerikanische Bürgerkriegsgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 HINDMAN

BY THE SUMMER OF 1862 THE CONFEDERCY WAS IN SERIOUS TROUBLE.. Southern military and naval forces west of the Appalachian Mountains had suffered an unrelieved string of defeats and disasters. Significant portions of Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Mississippi had fallen under Union control, and the Stars and Stripes flew over two state capitals, Nashville and Baton Rouge. All of the bustling commercial centers along the Mississippi River had been lost except Vicksburg, and it was uncertain whether the reeling Confederates could maintain their grip on that beleaguered citadel.

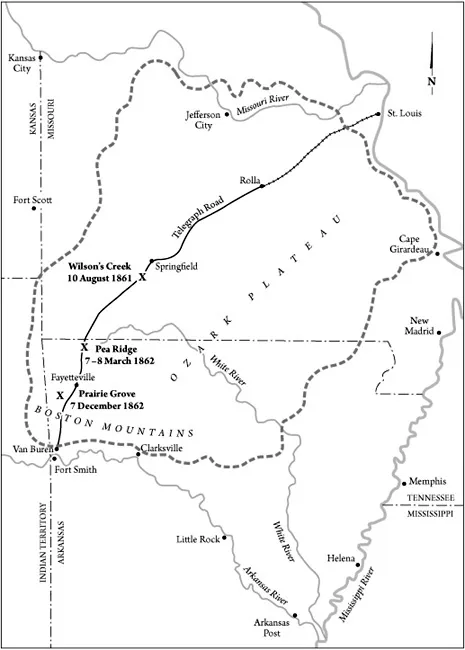

The situation was particularly grim in the trans-Mississippi Confederacy, an immense region composed of Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, the Indian Territory, the Arizona Territory, and, after a fashion, Missouri. Most Missourians were loyal to the Union, but a substantial minority favored secession and made a vigorous effort to bring the state into the southern fold. The secessionists suffered several early setbacks and were pushed into the southwest corner of the state around Springfield. There they rallied and won small but heartening victories at Carthage, Wilson’s Creek, and Lexington in the summer and early fall of 1861. The leader of the secessionist faction in Missouri, Governor Claiborne F. Jackson, was so encouraged by this turn of events that he convened a rump session of the state legislature in Neosho. To no one’s surprise, the legislators voted to leave the Union and join the Confederacy. By the close of 1861, the secessionists appeared to be gaining momentum. Then came a series of calamities from which the Confederate cause in the trans-Mississippi never recovered.

In early 1862, a Union army commanded by Major General Samuel R. Curtis drove into southwest Missouri. Sterling Price, commander of the secessionist Missouri State Guard, fled south with the Federals in hot pursuit. The Missourians joined forces with Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch’s Confederate army in northwest Arkansas and withdrew into the Boston Mountains. Curtis halted just inside Arkansas. He was satisfied at having rid Missouri of its Rebels and was determined not to let them return. The Confederates, of course, were equally determined to do exactly that. Major General Earl Van Dorn arrived from the East and combined Price’s and McCulloch’s forces into a single army under his overall command. He struck Curtis at Pea Ridge on 7–8 March 1862, but the outnumbered Federals stood their ground and won a decisive victory. Van Dorn retreated to the Arkansas River, his army wrecked and demoralized. Pea Ridge seemingly settled the fate of Missouri but left open the future of Arkansas and the Indian Territory.

Dispirited by his failure to recover Missouri, Van Dorn decided to try his luck elsewhere. Without consulting or even informing his superiors, he moved his entire force, along with all the arms, ammunition, stores, equipment, animals, and machinery that he could lay his hands on, to the east side of the Mississippi River. By the end of April the only Confederate forces left in Arkansas, Missouri, and the Indian Territory were a handful of cavalry regiments and a few hundred irregulars.1

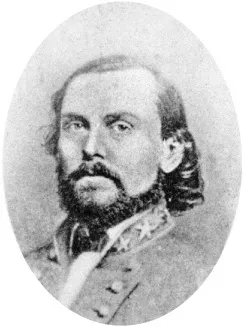

Arkansas was thrown into turmoil by this stunning development. Howls of outrage from political leaders and prominent citizens soon reached General Pierre G. T. Beauregard, who exercised nominal authority over the trans-Mississippi from his headquarters in Corinth, Mississippi. Under normal circumstances Beauregard would have referred a problem of this magnitude to the Confederate government in Richmond, but the urgency of the situation compelled him to act at once. Beauregard needed manpower after the recent bloodletting at Shiloh, so he decided against sending Van Dorn and his men back across the Mississippi. Instead, he appointed an interim commander for the abandoned trans-Mississippi. The man he chose was Major General Thomas C. Hindman Jr.

Thomas Hindman was a southerner to the core. Born in 1828 to a prosperous Tennessee family, he attended the Lawrenceville Classical Institute in New Jersey and was salutatorian of the class of 1843. He moved to Mississippi where he raised cotton and studied law. When the Mexican War broke out, Hindman joined the Second Mississippi and served capably as a junior officer. The regiment was ravaged by disease and saw no action, but after the war Hindman found his true calling in the arena of political combat.2

In 1854 Hindman left Mississippi to seek his fortune in the neighboring state of Arkansas. He must have found what he was looking for as soon as he set foot on Arkansas soil, for he settled in the port of Helena on the west bank of the Mississippi River. Hindman plunged into politics and quickly became a leading figure in the Democratic Party. His meteoric rise threw the state’s political establishment into turmoil and generated scores of enemies. Elected to Congress in 1858 and again in 1860, he was an uncompromising advocate of state’s rights and, ultimately, secession. Hindman was blessed with boundless energy and a remarkable gift for oratory. “I must say that as a speaker for the masses I never heard his superior,” recalled an acquaintance. His most memorable quality was a fiery temper. “Hindman had a wonderful talent to get into fusses,” said a friend, “from which he always came off either victor or with credit.” Friends and enemies alike—and he had plenty of both—described him as outspoken and confrontational. He rarely backed away from a scrape, and his political career was marked by a number of violent incidents.3

Hindman was short, slight, and fair-complexioned. He had blue eyes and his hair was a “light auburn, almost golden color, very fine, and worn long, combed, like a girl’s, carefully behind his ears.” As Hindman grew older he let his wavy locks grow longer, probably to compensate for a receding hairline. He dressed stylishly—he had a penchant for pastels—and undoubtedly was regarded as a dandy by many Arkansans. While campaigning for Congress in 1858, Hindman broke his left leg in a carriage accident; the bones did not heal properly, and the injured leg became two inches shorter than the other. Thereafter he wore a boot with a built-up heel and carried a cane.4

Hindman became close friends with another newcomer to Arkansas, an Anglo-Irish immigrant named Patrick R. Cleburne. In 1856 the two men engaged in a shootout with three members of the Know-Nothing Party on a Helena street in broad daylight. Both Hindman and Cleburne suffered serious chest wounds. Hindman recovered quickly but Cleburne lingered near death for several days. One member of the opposing group was killed, apparently by Hindman, but no charges were filed and everyone seemed to take the incident in stride. Politics in antebellum Arkansas clearly was not for sissies.5

When the Civil War began, Hindman resigned his seat in Congress and hurried home to organize military forces for the nascent Confederacy. He and Cleburne each led a brigade in Major General William J. Hardee’s corps at Shiloh in April 1862. Both men survived the hail of fire unscathed, but Hindman suffered another fractured leg when his horse went down. He was promoted to major general upon his recovery and given command of a division. In war as in politics, Hindman seemed destined for great things. Then came Beauregard’s request, made at the “earnest solicitation of the people of Arkansas,” that Hindman return to his adopted state and prevent the trans-Mississippi from going under. Hindman was reluctant to leave the Army of Tennessee where his star was in the ascendant, but after talking things over with Cleburne he accepted the challenge and set out for Arkansas. “In the existing condition of things General Beauregard could not spare me a soldier, a gun, a pound of powder, nor a single dollar of money,” Hindman recalled. He may have been flattered by the thought that Beauregard considered him a one-man army.6

Thomas C. Hindman (Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Va.)

On 31 May 1862 Hindman arrived in Little Rock and assumed command of the newly created Trans-Mississippi District, which consisted of Arkansas, Missouri, and the Indian Territory. The desperate state of affairs in the district came as a profound shock. “I found here almost nothing,” Hindman informed the War Department in Richmond. “Nearly everything of value was taken away by General Van Dorn.” Undaunted, Hindman set to work. His first act was to issue a ringing declaration that began: “I have come here to drive out the invader or to perish in the attempt.” That statement was no rhetorical flourish; Hindman meant every word of it.7

The Trans-Mississippi District was under attack from two directions when Hindman assumed command. Following his victory at Pea Ridge in the spring, Curtis carried the war deep into Arkansas. He advanced to within forty miles of Little Rock before his line of communications broke down, then turned toward the Mississippi River where he could obtain supplies by way of the Union navy. Hindman appealed to Arkansans in Curtis’s path to burn their crops and poison their wells, but his call for a “scorched earth” campaign was largely ignored. In mid-July Curtis occupied Helena. For the rest of the war the town was a Union enclave, and the handsome new Hindman residence was Union headquarters.8

While Curtis headed toward Helena, Colonel William Weer advanced into the Indian Territory from Kansas. A resounding Union victory at Locust Grove convinced more than a thousand disillusioned Cherokees, many of whom had fought in Van Dorn’s ranks at Pea Ridge, to change sides. The swelling Union force reached Fort Gibson and Tahlequah in mid-July but could go no farther because of a brutal drought that dried up springs and reduced rivers to a trickle. Weer was removed from command by his subordinates, who promptly fell to squabbling among themselves. Parched and paralyzed, the Federals gave up and returned to Kansas.9

Curtis and Weer marched almost at will across large swatches of Arkansas and the Indian Territory during the summer of 1862. Their forces overran thousands of square miles of Confederate territory and seized or destroyed property worth tens of millions of dollars, much of it in the form of slaves who followed the blue columns to an uncertain freedom. The incursions were hindered more by distance and nature than by organized resistance. Confederate forces, such as they were, achieved little except to annoy the Federals. But when the dust settled and the fires burned out, the only permanent territorial loss suffered by the Confederacy was Helena, which would have fallen to Union gunboats had Curtis not gotten there first. Hindman could hardly believe his good fortune, though his relief was tempered by the certainty that the Federals would resume offensive operations in the near future. It was imperative that the Confederates meet them on more equal terms.

A more immediate problem was the breakdown in public order. The presence of Union forces in Arkansas and the Indian Territory generated a resurgence of Unionist sentiment that led to widespread disaffection. Judges, sheriffs, tax collectors, jailers, and other officials failed to carry out their duties or were prevented from doing so. With courts closed, jails open, and law enforcement suspended, some areas teetered on the verge of anarchy barely a year after the start of the war. Arkansas governor Henry M. Rector and the state legislature proved incapable of dealing with the situation. Conditions were even worse in the Indian Territory, where the Cherokee tribal government ceased to function altogether.10

Alarmed by what he described as the “virtual abdication of the civil authorities,” Hindman declared martial law throughout the Trans-Mississippi District. “Immediately he commenced issuing military orders, which under his vigorous government had all the force of Imperial decrees,” recalled an Arkansas industrialist named Henry Merrell. “Bad as it seems that there should ever be so much power in one man, it was in General Hindman’s case a very great improvement upon the state of things before his coming, and quiet citizens in our part of the country breathed freely once more.” Not everyone agreed, of course. There was the usual overheated rhetoric decrying “tyrannical acts” and “military despotism,” but most Arkansans discovered that Hindman’s heavy-handed approach got results. The Little Rock True Democrat, the state’s largest and most influential newspaper, supported the temporary imposition of martial law as a necessary evil. “It is the only means at hand to afford protection, and every good citizen should lend his earnest assistance to promote its success,” opined editor Richard H. Johnson.11

In his dual roles as district commander and (self-appointed) military governor, Hindman demonstrated what diligence, determination, and a disregard for legalities could accomplish. “His genius was especially administrative,” remarked a Confederate officer who knew Hindman well. “Nothing escaped his vigilance and his energy. Resources, arms, supplies and army sprang into being almost by the magic of his will.” Merrell noticed that after Hindman assumed control, a “kind of nervous energy was infused into every department of Government within his reach” and that no corner of the state was unaffected. “The whole country was taught that she could clothe, subsist and manufacture for her own necessities,” marveled another officer. Acting on his own authority, Hindman awarded military contracts and established facilities to manufacture arms, ammunition, clothing, shoes, camp equipment, medicines, harnesses, and wagons. He set price controls to stamp out profiteering and minimize inflation. He burned tons of cotton to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. He pared away incompetent and inefficient officers regardless of their political connections. He rigorously enforced the Conscription Act and established camps of instruction. He interpreted the Partisan Ranger Act in the broadest possible fashion and authorized the formation of irregular bands to harass Union forces and Unionists. All the while he badgered authorities in Richmond for more men, more arms, more supplies, more funds, more of everything.12

The barrage of appeals, requests, and demands produced results. A large number of Missouri State Guard troops had refused to transfer to Confederate service during the Pea Ridge campaign. Van Dorn carried them off to Mississippi despite their status as civilian militiamen. The irate Missourians clamored to return to their state or at least to their side of the Mississippi River, a demand that Hindman strongly seconded. The War Department finally gave in. In late summer Brigadier General Mosby M. Parsons and nine hundred veterans of Wilson’s Creek and Pea Ridge made their way back to Arkansas. This was the only occasion during the Civil War when a Confederate force of any size crossed the Mississippi from east to west.13

Hindman envisioned Parsons’s command as the nucleus of a strong Missouri component in the army he was cobbling together. The Conscription Act could not be enforced in Missouri because a Unionist administration was in control of the state government, so Hindman launched a recruiting drive unique in Confederate history. During the summer of 1862 he sent dozens of Missouri State Guard and Confederate officers back to their home state. Some traveled alone or with a handful of companions, others were accompanied by small cavalry forces. They spread the news that Hindman was assembling an army in Arkansas capable of restoring Missouri to the Confederacy, and they encouraged fellow secessionists to take part in the climactic struggle by enlisting in regular forces or joining irregular bands on their home ground.14

The recruiters found receptive audiences, particularly in the “Little Dixie” region of west-central Missouri where sympathy for secession was wide and deep. Thousands of men took off for camps of instruction in Arkansas; thousands more took to the brush in Missouri. Emboldened by larger numbers and the promise of regular military support in the near future, guerrillas swarmed out of their hiding places and threw the state into turmoil. Ambushes, skirmishes, and small battles flared all across Missouri. Union authorities from St. Louis to Kansas City were caught off guard by the sudden shift in the military situation.15

When Hindman reached Little Rock at the end of May, Missouri was gone and Arkansas and the Indian Territory were practically defenseless. Union military forces were on the move from the Mississippi River to the Great Plains. Ten weeks later everything had changed. Federal offensive operations had come to a standstill. More than 20,000 Confederate troops—forty regiments of infantry and cavalry and a dozen batteries of artillery—were in the field or in camps of instruction in Arkansas and the Indian Territory. Thousands more were in irregular service, mostly in Missouri. The Confederacy west of the Mississippi River had come back from the dead.16

In only seventy days Hindman had created an embryonic army and a rudimentary logistical base in the least populous and least developed part of the Confederacy. It was an achievement without parallel in the Civil War. Nevertheless, his accomplishments were overshadowed by the rigorous and sometimes extralegal methods he employed. Hindman viewed war as a serious business. From the day he assumed command in Little Rock he made it clear that he expected everyone to make sacrifices to achieve victory. In short, Hindman demanded a level of commitment to the cause of southern independence that not every southerner was willing to make. Most Confederate citizens supported secession and independence in the abstract, but the harsh reality of war—shortages, inflation, hardships, destruction, and death—was more than many had bargained for.

Southern Missouri and northern Arkansas in 1861–62

The political and economic elites in Arkansas were particularly outraged by Hindman’s insistence that they make sacrifices lik...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- FIELDS OF BLOOD

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Maps

- Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 HINDMAN

- 2 FEDERALS

- 3 RETURN TO ARKANSAS

- 4 THE BOSTON MOUNTAINS

- 5 WAR OF NERVES

- 6 DOWN IN THE VALLEY

- 7 CANE HILL

- 8 RACE TO PRAIRIE GROVE

- 9 OPENING MOVES

- 10 ARTILLERY DUEL

- 11 HERRON STORMS THE RIDGE

- 12 FIGHT FOR THE BORDEN HOUSE

- 13 BLUNT SAVES THE DAY

- 14 CHANGE OF FRONT

- 15 CONFEDERATE SUNSET

- 16 RETREAT

- 17 AFTERMATH

- 18 RAID ON VAN BUREN

- 19 EPILOGUE

- APPENDIX: Order of Battle

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index