![]()

1: A Perfectly Irresistible Change

The Transformation of East Coast Agriculture

There is nothing particularly new about migrant labor in North America. The continent’s earliest human inhabitants were nomadic hunters who crossed a land bridge from Siberia as early as 40,000 years ago in search of caribou and woolly mammoths. The first Europeans who came “to Plant an English nation” at Roanoke 500 years ago were followed by thousands of immigrant workers: farmers and artisans, servants and slaves. Indeed, American history is in large part the saga of successive waves of migrant workers and the conflicts and cultures they wrought. What distinguishes labor migrations in the “Age of Capital” from earlier movements of working people is less the total absence of woolly mammoths than the preeminence of wage labor. By the nineteenth century more people than ever were moving great distances to sell their labor power at a price.1

What was new also in the late nineteenth century was the growing importance of migrant labor to agriculture in the United States. In the hops fields of California, the beet farms of Michigan, the strawberry fields of Virginia, and the potato farms and cranberry bogs of New Jersey, farm owners relied on men, women, and children who would appear in time for the harvest and disappear thereafter.

Agriculture the world over had always been characterized by short seasons of intensive labor. But in the decades after the Civil War two changes transformed agriculture more dramatically than anything since Jethro Tull invented the plow. The first was the widespread availability of horse-drawn agricultural machinery. The second was the rapid worldwide rise of cides, whose inhabitants had to be fed. These changes led American farmers to plant new crops in new ways and sent them scurrying in search of new sources of labor.

New Jersey farmers were particularly well placed to supply perishable produce to city people as their crops grew in the shadow of New York, Philadelphia, Newark, and a score of smaller industrial cities. Their success made South Jersey the ideological center of “progressive” agriculture and transformed farmers in the Garden State into buyers on the international labor market.

The labor they bought was sold to them by Italian immigrants—mostly women and children who lived in nearby Philadelphia—and African American men from the upper South. Farm labor was unpleasant work, but for those who enjoyed few other opportunides, it was a way to earn quick cash in a world of account books, pawnshops, and eviction notices.

This story begins, however, not in New Jersey but in the vast, sparsely settled lands of the Dakota Territory’s Red River Valley, where mechanized farm producdon first reached massive propordons. When economic depression struck in 1873, the directors of the Northern Pacific were left with railroad tracks that ended in what seemed to be the middle of nowhere. The Sioux had recently been expelled from the region, but the vast expanse of prairie that the federal government conquered and then gave to the railroad was uncultivated and apparently infertile. Not certain if they were opdmists or fools, the railroad’s directors and investors gambled that, if they could demonstrate the land’s fertility, they could both profit from the sale of wheat and attract settlers to the valley. Once settlers were ready to ship their own grain out of the region, the railroad would be back in business. Together the company’s officers traded their nearly worthless bonds for large portions of the railroad’s land, hired an experienced wheat grower and ex-lawyer to manage their operation, and ordered him to turn the land almost exclusively to wheat2

Others soon followed their example. The Grandin brothers of Pennsylvania also exchanged their Northern Pacific securities for 100,000 acres of rich, black Red River Valley soil. Seemingly undaunted by the vicissitudes of a crash-and-boom economy, the Grandin brothers made the Dakota Territory their Palestine and reconsecrated their faith in the holy trinity of men, monopoly, and machinery. They hired the same ex-attorney and wheat grower to manage their colony, supplied him with steel plows, cultivators, and harvesters, and ordered the land planted, not with settíers, but with 61,000 acres of wheat. The seeds of hope and profit that had failed with the Northern Pacific were thus replanted on the enormous, highly mechanized estates that soon came to be known across the nation as “bonanza farms.”3

These massive, mechanized estates of the West were not typical of late nineteenth-century agriculture. In fact, they were not even typical of landholding in the Dakota Territory, which came to be characterized by much smaller, family-owned farms. But it was the bonanza farms, not the family farms of German and Swedish settlers, that captured the imagination of the nation’s prophets of progress and symbolized the boom in agricultural production that would flood grain markets the world over. Indeed the bonanza farms monopolized the nation’s dailies and magazines, much as they monopolized the best lands of the West. There they were presented to contemporaries as harbingers of a new era of harmony between agriculture and industry and as models of efficiency and productivity.

The Grandin brothers and other absentee bonanza farm owners may have been captains of agricultural industry, but they were less innovators than they were the beneficiaries of fifty years of improvements in farm implements. John T. Alexander’s 80,000-acre estate, capitalized at perhaps a half-million dollars, employed 150 steel plows, 75 breaking plows, and 142 cultivators.4 But what had occurred in the preceding half-century was not so much a revolution in farm technology as it was an application of the intellectual and material products of industry—size, steel, and speed—to agriculture. The horse-powered machines of the Civil War era hardly differed in concept from the scythes, sickles, plows, and flails that had been in use in agriculture for a thousand years, but the strength and durability of steel over wood gave postwar farmers increased power, speed, and proficiency.5

Although John Deere’s all-steel plow went on the market in 1847, agricultural mechanization remained relatively unimportant until the outbreak of the Civil War. Once the war was under way, however, the dearth of labor and spiraling grain prices catapulted the farmers of the West and Midwest into the machine age. Over 100,000 reapers were used in 1861, and the mechanization of all operations between plowing and harvesting followed with a flurry of new patents and improvements.

The urgency with which improvement followed improvement was assured by the inflexible schedule imposed by nature. The production of a crop involved five tasks: preparing the soil, seeding, cultivating, harvesting, and preparing the harvested crop for market. No matter how great the demand for a particular product, the amount that could be planted was always constrained by the amount of labor needed to cultivate and harvest the crop. Any change in the machinery available for one of the five operations affected the rest. Improved plows made it possible for farmers to plant greater acreage, but growth was still limited to the amount that could be harvested by scythe and cradle. The mechanization of the soil preparation process thus created a bottleneck that could only be solved by the mechanization of the other four operations. The greatest bottleneck was the harvest, which had to be accomplished in the least amount of lime and required the greatest amount of labor.6

By the end of the Civil War almost every demand of grain production was met by a whirl of horse-drawn steel. Perhaps 250,000 reapers harvested the grain that fed the Union army, and plows, harrows, drills, planters, binders, spreaders, and threshers all assisted in the process.7The ability to mechanize every stage of wheat production was thus the bonanza farmers’ inheritance. They simply took this bequest and used it to hold down the largest expense of wheat production after land and equipment: labor.

Mechanization dramatically increased the productivity of labor. An early McCormick reaper could cut twelve to fifteen acres of wheat in a ten-hour day, while an individual could cut only one-half to three-quarters of an acre with a sickle. But machines still required operators, and on a farm five times the area of Manhattan, one could hardly call on one’s neighbors for assistance.8 On the Grandin estate the workforce ranged from only to men during the five coldest months of the year to 200 to 500 during the harvest in August and September. Harvesting and threshing crews traveled from estate to estate, starting in Kansas and following the ripening wheat northward into Dakota, Minnesota, and sometimes Canada.9

Having demonstrated the fertility of the land by producing as many as 5,000 bushels of wheat for every 100 inhabitants of the valley, the Northern Pacific joined with the Milwaukee and North-Western railroads “and with one accord flooded the country with literature,” wrote an observer for the World To-Day. As if by summons the setüers arrived. When they reported home that opportunities had not been exaggerated, “others came flocking into Dakota and Minnesota by hundreds and by thousands.” “Marvellous the change,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine heralded, “in 1869 a furrowless plain; 1879, a harvest of eight million bushels of grain—ere long to be eighty million.” In another five years the region’s population had increased 279 percent and wheat production was up 645 percent; every 100 inhabitants now produced 11,500 bushels of wheat.10

“How invention has simplified husbandry,” the nation’s magazines marveled: “The employment of capital has accomplished a beneficent end, by demonstrating that the region, instead of being incapable of settlement, is one of the fairest sections of the continent.11 The Red River Valley was not alone in its bounty. In the United States as a whole over 21.5 million more acres were devoted to cereals in 18go than just ten years before. Between 1860 and 1910 the number of farms and the acreage of improved farmland trebled.12

Wheat production increased beyond all expectations, but the nation’s wheat growers did not get rich. By the turn of the century the nation’s farmers were producing six times more wheat than they had harvested a halfcentury before, but their share of the nation’s wealth was less than half of what it had been in 1860. The railroads’ reports of opportunities in the West had, in fact, been exaggerated. From 1875 to 1883 “uniformly large yields and high prices prevailed,” but this was more a matter of good fortune than the magic of machines. Wheat prices were uncommonly high because Europe’s wheat crop had failed several years running, and yields were encouraged by unusually wet weather and a brief lull in the voracious attacks of grasshoppers. By the mid-1880s rising taxes, drought conditions, and falling prices proved to absentee owners that speculation in large-scale farming was at least as risky as speculation in railroads. By the 1890s the bonanza farms were virtually gone, broken up and sold off to German, Swedish, and native-born families brought west by the Northern Pacific on special excursion trains. Only on the Pacific Coast did such massive estates remain.13

The settlers who bought pieces of the bonanza farms found that rising interest rates on mortgaged land ate away their savings about as fast as a grasshopper could chew through a stalk of wheat. Without cash the necessity of buying machines and hiring men forced them quickly into debt.14 With railroad directors out of the wheat-growing business, farmers also found freight rates less favorable and storage prices nearly criminal. As farm sizes shrank and tenancy, indebtedness, and bankruptcy rates expanded, western farmers responded by growing more wheat. Even as they organized farmers’ alliances and channeled their frustrations into the populist movement, western farmers flooded world markets, including East Coast markets, with wheat.

The most immediate, obvious, and lamented effect of western wheat production on the East Coast was the abandonment of eastern farms. With eroded soil and small farms broken up into plots “hardly larger than a Western corral,” eastern growers were unable to compete with the staples produced on the vast, fertile, and less costly lands of the West. Peculiarly unsuited to large-scale mechanization because of their uneven terrain and rocky soil, northeastern farms were transformed by mechanized staple producuon in the West, not because northeastern growers emulated its example, but because they lost their markets to the volume and cheapness of western grain.15

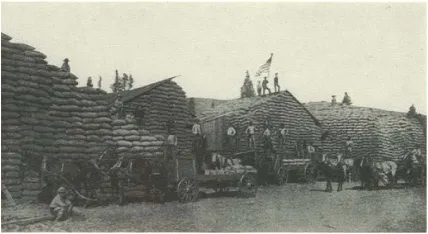

“Sacked wheat produced in the West awaiting shipment to world markets” (World To-Day magazine, 1905)

While the number of farms in the nation increased throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, the North Adantic region alone reported a decline. From 1880 to 1890 twenty-six states increased their acreage in cereals, while northeastern farmers took over 5 million acres out of producuon and produced over 10 percent less grain. In some northeastern regions the decline was far more dramatic. Between 1860 and 1899 New England’s wheat producuon plummeted from 1 million bushels a year to just 137,000.16

To contemporaries the effects of western competition were tragic. As one observer noted in 1890, “The New England farmer has found his products selling at lower prices because of the new, fierce, and rapidly increasing competition. One by one he has had to abandon the growing of this or that crop because the West crowded him beyond the paying point.” The Nation, after considering “a cumulaüve mass of evidence that is perfectly irresistible,” determined that the state of Massachusetts’s agriculture could be summed up in two words: “rapid decay.” Among the signs were absentee owners, sagging productivity, lower wages, “a more ignorant population,” and increasing numbers of women employed at hard outdoor labor, “the surest sign of a declining civilization.” Maine’s Board of Labor counted 3,398 abandoned farms in 1890. Massachusetts published A Descriptive List of Farms . . . Abandoned or Partially Abandoned. Connecticut released a Descriptive Catalogue of Farms for Sale, and Vermont issued a List of Desirable Farms at Low Prices. Farther south the warnings were just as dire. In New Jersey, Gloucester County officials reported to the State Board of Agriculture in 1890 that land values had fallen 40 percent in twenty years due to overproduction; the opening of cheap, fertile lands in the West; and increased railroad facilities, “which bring all parts of this country in competition with us.” Such were the symptoms of a seemingly incurable affliction. Despite their proximity to urban markets, eastern growers simply could not compete with the volume and prices of western products.17

Even the nation’s monthly magazines, which usually devoted their space to glowing accounts of resort towns, joined in the lament for East Coast farms. Century Magazine blamed the “rich and level Western prairies, with their farm machinery and cheap transportation,” for the decay of the stony, hilly farmsteads of the East, which once furnished wheat and corn for an eastern market ...