eBook - ePub

Talkin' Tar Heel

How Our Voices Tell the Story of North Carolina

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Are you considered a “dingbatter,” or outsider, when you visit the Outer Banks?

Have you ever noticed a picture in your house hanging a little “sigogglin,” or crooked?

Do you enjoy spending time with your “buddyrow,” or close friend?

Drawing on over two decades of research and 3,000 recorded interviews from every corner of the state, Walt Wolfram and Jeffrey Reaser’s lively book introduces readers to the unique regional, social, and ethnic dialects of North Carolina, as well as its major languages, including American Indian languages and Spanish. Considering how we speak as a reflection of our past and present, Wolfram and Reaser show how languages and dialects are a fascinating way to understand our state’s rich and diverse cultural heritage. The book is enhanced by maps and illustrations and augmented by more than 100 audio and video recordings, which can be found online at talkintarheel.com.

Have you ever noticed a picture in your house hanging a little “sigogglin,” or crooked?

Do you enjoy spending time with your “buddyrow,” or close friend?

Drawing on over two decades of research and 3,000 recorded interviews from every corner of the state, Walt Wolfram and Jeffrey Reaser’s lively book introduces readers to the unique regional, social, and ethnic dialects of North Carolina, as well as its major languages, including American Indian languages and Spanish. Considering how we speak as a reflection of our past and present, Wolfram and Reaser show how languages and dialects are a fascinating way to understand our state’s rich and diverse cultural heritage. The book is enhanced by maps and illustrations and augmented by more than 100 audio and video recordings, which can be found online at talkintarheel.com.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Talkin' Tar Heel by Walt Wolfram,Jeffrey Reaser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Tar Heels in North Cackalacky

I think North Carolina has a level of cultural and historical resources that are unsurpassed nationally. We are known and envied across the country. —LINDA CARLISLE, secretary of the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, quoted in the Raleigh News and Observer, December 9, 2011

“From Manteo to Murphy” (or “from Murphy to Manteo”) is a common expression used throughout North Carolina. The idiom spans 475 miles (544 driving miles)—from the Intracoastal Waterway community of Manteo (population 1,500) on Roanoke Island, located at the site of the first English settlement in North America, to the southwestern border town of Murphy (population 1,700), nestled in the Smoky Mountains. The physical geography extends from the most expansive coastal estuary on the East Coast of the United States to the lush, rock-garden vegetation of the Smoky Mountains. But “Manteo to Murphy” refers to much more than distance and topography. History, tradition, arts, food, and sports also define the cultural landscape.

North Carolinians like their state a lot, and so do the 50 million yearly visitors. We are surprised by how many people we encounter who decided to move to North Carolina without any previous connection to the state—and even without a destination job—simply because it seemed like a good place to live. North Carolina is not shy about marketing its resources as one of the top states for both living and vacationing. There is, however, one notable characteristic that rarely makes it into advertisements about its cultural and historical resources: its language and dialect heritage. Language reflects where people come from, how they have developed, and how they identify themselves regionally and socially. In some respects, language is simply another artifact of history and culture, but language variation is unlike other cultural and historical landmarks. We don’t need to visit a historical monument, go to an exhibit, view an artist’s gallery, or attend an athletic event to witness it firsthand; language resonates in the sounds of ordinary speakers in everyday conversation. Other landmarks recount the past; language simultaneously indexes the past, present, and future of the state and its residents. The voices of North Carolinians reflect the diversity of its people. They came to this region in different eras from different places under varied conditions and established diverse communities based on the natural resources of the land and waterways. The range of settlers extends from the first American Indians who arrived here at least a couple of thousand years ago from other regions in North America to the most recent Latino immigrants from Central and South America in the late twentieth century. The diverse origins and the migratory routes that brought people to North Carolina have led to a diffuse, multilayered cultural and linguistic panorama that continues to evolve along with the ever-changing profiles of its people.

Dialects and Legacy

When Walt Wolfram first moved to North Carolina in 1992, he often described his midlife passage as “dying and going to dialect heaven.” Since then, he and the staff of the North Carolina Language and Life Project (NCLLP) have conducted several thousand interviews with residents of the state—literally from Manteo to Murphy—which have only reaffirmed his observation (though his colleagues may have tired of hearing his heavenly proclamation). So why is North Carolina so linguistically intriguing? And why has this richness not been celebrated in the same way as other cultural and historical treasures of the Tar Heel State?

The conditions for dialect and language diversity are tied closely to physical geography and the human ecology of the region that eventually became known as North Carolina. From the eastern estuaries along the Atlantic Ocean, the terrain transitions into the Coastal Plain, the Piedmont, and the mountains of southern Appalachia—from sand to rich loam, to red clay, to mixed rock and dirt. The varied soils and climates contribute to diverse vegetation, wildlife, natural resources, and cultural economies. Waves of migration at different periods originating from different locations here and abroad have helped establish communities in both convenient and out-of-the-way areas that still reveal a distinct “founder effect” in language even centuries after settlement. (Founder effect is the term linguists use for a lasting influence from the language variety of the first dominant group of speakers to occupy an area.) So, the western mountains of North Carolina still bear the imprint of Scots-Irish English, brought by the many settlers who came from their homeland to Philadelphia before traveling west and south on the Great Wagon Road in the early 1800s.1 For example, the use of anymore in affirmative sentences such as “We watch a lot of videos anymore,” the use of you’uns for plural you in “You’uns can tell some Jack Tales,” and the use of whenever to refer to “at the time that” as in “Whenever I was young I would do that” can all be attributed to the lasting influence of linguistic traits originally brought by the Scots-Irish. In fact, the current use of anymore in positive sentences follows the migration route from Philadelphia through western Pennsylvania and down the Great Wagon Road, diffusing outward from this path as travelers set up communities along the way.

Similarly, the coastal region and the Outer Banks still echo the dialect influence of those who journeyed south by water from the coastal areas of Virginia. Dialect features like the use of weren’t in “I weren’t there,” the pronunciation of high tide as hoi toid, and the pronunciation of brown more like brane or brain are shared along this and adjoining estuaries. The interconnected waterways and the settlement history help explain why speakers from North Carolina Outer Banks communities, such as Ocracoke and Harkers Island, sound much more like the speakers of Virginia’s Tangier Island and Maryland’s Smith Island in the Chesapeake Bay than they do the speakers of inland North Carolina. Mix in the contributions of American Indian languages; the remnants of African languages; and Europeans speaking Gaelic, German, French, and other languages, and the result is a regional and ethnic language ecology as varied as North Carolina’s physical topography and climate—the most varied of any state east of the Mississippi River.

Tar Heels in North Cackalacky

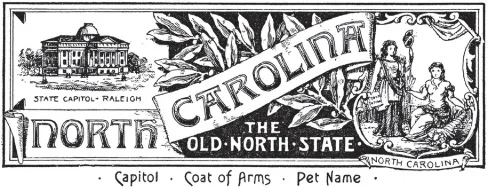

States commonly bear nicknames that highlight some attribute of the state, ranging from shape (for example, Keystone State for Pennsylvania) and location (Bay State for Massachusetts; Ocean State for Rhode Island) to its natural resources (Granite State for New Hampshire; Peach State for Georgia) or even presumed character attributes of the people (Show-Me State for Missouri; Equality State for Wyoming). There is always a story behind the nickname. Carolina, derived from Carolus, the Latin word for Charles, was originally named after King Charles I in 1629. The land from Albemarle Sound in the north to St. Johns River in present-day South Carolina was appropriated in the original territorial designation. When Carolina was divided into North Carolina and South Carolina officially in 1729, the older settlement in North Carolina was referred to as the Old North State, a nickname commonly used for a variety of purposes, including a state banner from 1893 (Figure 1.1). The official song of North Carolina, “The Old North State,” was adopted by the State Assembly in 1927. Though less common today, the nickname is still used on occasion.

FIGURE 1.1. The state banner of North Carolina, 1893. (Florida Center for Instructional Technology)

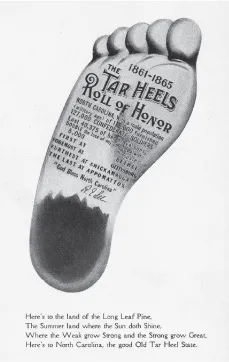

North Carolina, however, is much more frequently called the Tar Heel State, most likely alluding to major products of the colonial era—tar pitch and turpentine made from the longleaf and loblolly pine trees so prominent in the state. Earlier legends attribute the name to the laborers who walked out of the woods with the sticky black substance on their shoes or to stories of incidents during wars. One legend comes from the Revolutionary War, when North Carolina soldiers continued marching after wading through a river coated with liquid tar, but the most popular stories involve the Civil War, when the tar and turpentine industries were flourishing. One story, preserved in the Creecy Family Papers, reports that a regiment from Virginia supporting the North Carolina troops was driven from the field, leaving the North Carolina troops to fight alone. After the battle was won by the North Carolinians, they were greeted by the deserting soldiers from Virginia with the question, “Any more tar down in the Old North State, boys?” The North Carolinians responded, “No; not a bit, old Jeff’s bought it all up,” referring to Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America at the time. When asked by the abandoning regiment what old Jeff was going to do with it, they were told: “He’s going to put it on you’ns heels to make you stick better in the next fight.” The legend continues that General Robert E. Lee was told about this incident, to which he responded, “God bless the Tar Heel boys”—and the name stuck.2

FIGURE 1.2. The Tar Heels Roll of Honor. (North Carolina Collection, UNC–Chapel Hill archives)

A less-flattering story of the origin of Tar Heel was recorded in John S. Farmer’s Americanisms, Old and New, published in 1889.3 He recounts a battle involving Mississippi and North Carolina soldiers in which the brigade of North Carolinians performed poorly. According to Farmer, the Mississippians taunted the North Carolinians about their failure to tar their heels in the morning, leaving them unable to hold their position.

People from North Carolina have also been referred to as Tar Boilers in reference to the distillation process used for producing tar and pitch. Pine logs were stacked and covered with dirt and burned, the tar running through channels on the low side of the pile—a messy and smelly process. In fact, poet Walt Whitman derisively referred to North Carolinians as Tar Boilers in 1888.4 This term faded, however, while Tar Heel has remained.

For a period after the Civil War, Tar Heel was viewed as a derogatory reference to North Carolinians, but it was rehabilitated by the turn of the twentieth century. Once a state nickname becomes associated with a university sports program, it sticks—much to the chagrin of rival athletic programs. The fact that Tar Heels as a nickname has been appropriated by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has certainly promoted its visibility and popularity. But those from rival state universities, such as North Carolina State University and East Carolina University, would prefer not to talk about the Tar Heel Nation as if it were synonymous with the state where they have competing athletic programs. The popularity of the nickname, however, is clear, and a book titled Talkin’ Tar Heel might just as readily be interpreted as a description of speech by students and staff on the UNC–Chapel Hill campus as a book about the speech of North Carolinians.

Tar Heel and Old North State are not the only nicknames for North Carolina, though competing monikers like Land of the Sky, Turpentine State, or Good Roads State have little popular currency. One of the popular and spreading nicknames for the state and its neighbor to the south, however, is the term Cackalacky. North Cackalacky and South Cackalacky, or their abbreviated forms, North Cack and South Cack, have both increased in popularity in recent years. The term’s currency is strong enough that it has been appropriated by commercial products that wish to reflect their regional heritage. Original Cackalacky Spice Sauce, a zesty, sweet potato–based sauce, was trademarked in 2001 and is now distributed in twenty-six states.5 The term Cackalacky for a sweet potato–based sauce is fitting since North Carolina produces approximately 40 percent of all the sweet potatoes consumed in the United States. In 1995 the tuber was designated as the state vegetable of North Carolina following a two-year campaign initiated by a group of fourth graders from Elvie Street School in Wilson.6 While the origin of Cackalacky is still uncertain, its history began long before the sauce was created. At the very least, we can definitively trace the term to 1937, when it was used in a popular song. It is likely that Cackalacky’s etymology runs much deeper than this song, however, and there remains much popular speculation and discussion about its possible origins.

The term may have arisen from a kind of sound-play utterance used to refer to the rural ways of people from Carolina—a play on the pronunciation of the state. Another hypothesis is that Cackalacky was derived from the Cherokee term tsalaki, pronounced as “cha-lak-ee,” the Cherokee pronunciation of Cherokee. Yet another hypothesis traces it to a cappella gospel groups in the American South in the 1930s, who used the rhythmic (but apparently meaningless) chant clanka lanka in their songs. Derivations related to the German word for cockroach (kakerlake) and a Scottish soup (cocklaleekie) have also been suggested, but no one really knows the origin. Certainly, the popularity of Cackalacky has risen in the last decade, and it has now become a positive term of solidarity used throughout the state. We favor the sound-play etymology for C...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Talkin’ Tar Heel

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Tar Heels in North Cackalacky

- 2. The Origins of Language Diversity in North Carolina

- 3. Landscaping Dialect

- 4. Talkin’ Country and City

- 5. The Outer Banks Brogue

- 6. Mountain Talk

- 7. African American Speech in North Carolina

- 8. The Legacy of American Indian Languages

- 9. Lumbee English

- 10. Carolina del Norte

- 11. Celebrating Language Diversity

- Notes

- Index of Dialect Words and Phrases

- Index of Subjects