eBook - ePub

The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture

Volume 5: Language

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture

Volume 5: Language

About this book

The fifth volume of The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture explores language and dialect in the South, including English and its numerous regional variants, Native American languages, and other non-English languages spoken over time by the region’s immigrant communities.

Among the more than sixty entries are eleven on indigenous languages and major essays on French, Spanish, and German. Each of these provides both historical and contemporary perspectives, identifying the language’s location, number of speakers, vitality, and sample distinctive features. The book acknowledges the role of immigration in spreading features of Southern English to other regions and countries and in bringing linguistic influences from Europe and Africa to Southern English. The fascinating patchwork of English dialects is also fully presented, from African American English, Gullah, and Cajun English to the English spoken in Appalachia, the Ozarks, the Outer Banks, the Chesapeake Bay Islands, Charleston, and elsewhere. Topical entries discuss ongoing changes in the pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar of English in the increasingly mobile South, as well as naming patterns, storytelling, preaching styles, and politeness, all of which deal with ways language is woven into southern culture.

Among the more than sixty entries are eleven on indigenous languages and major essays on French, Spanish, and German. Each of these provides both historical and contemporary perspectives, identifying the language’s location, number of speakers, vitality, and sample distinctive features. The book acknowledges the role of immigration in spreading features of Southern English to other regions and countries and in bringing linguistic influences from Europe and Africa to Southern English. The fascinating patchwork of English dialects is also fully presented, from African American English, Gullah, and Cajun English to the English spoken in Appalachia, the Ozarks, the Outer Banks, the Chesapeake Bay Islands, Charleston, and elsewhere. Topical entries discuss ongoing changes in the pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar of English in the increasingly mobile South, as well as naming patterns, storytelling, preaching styles, and politeness, all of which deal with ways language is woven into southern culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture by Michael B. Montgomery, Ellen Johnson, Michael B. Montgomery,Ellen Johnson, Charles Reagan Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781469616629Subtopic

North American HistoryLANGUAGE IN THE SOUTH

Few traits identify southerners so readily as the way they talk. It is often the first thing nonsoutherners notice about them, sometimes ridiculing southern speech as being “uneducated” or “incorrect” but at other times admiring it as “down-to-earth,” “friendly,” or “polite.” Southerners are frequently renowned for their linguistic skills and verbal dexterity, whether as raconteurs, preachers, politickers, or just good talkers. When Georgian Jimmy Carter and Arkansan Bill Clinton ran for the presidency, the country took notice of their speech, and the media gave it much attention, curious about and often baffled by it. Carter’s campaign spawned a rash of paperbacks of the How to Speak Southern ilk in 1976. Bubba jokebooks and one-liners played off the candidacy of “the man from Hope” in 1992, and when Clinton responded to a reporter’s question on the campaign trail with the common regionalism “That dog won’t hunt,” journalists were quick to phone linguists at southern universities for a translation. For many southerners, the way they speak English marks their loyalties, their upbringing, their roots, and their identity, even if it often provokes stereotypes and prejudice when they travel, and not infrequently in southern schoolrooms as well.

Although the South is the most distinctive speech region in the United States, it is also the most diverse, little more uniform than the nation as a whole. Outsiders may think that all southerners talk pretty much alike, but southerners certainly know better. Some of the most unusual types of American English are found on the periphery of the South, in areas such as the southern Appalachian and Ozark mountains and such coastal areas as the Outer Banks of North Carolina, the Chesapeake Bay Islands of Virginia, and the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia. But these varieties only begin to outline the linguistic picture of the region. Even so, many accounts, both popular and scholarly, have regrettably obscured the diversity of speech within the region by contrasting a generalized “Southern English” with “General American English” or “Standard English,” the latter two being abstract, even hypothetical entities never described and certainly not homogeneous. Even the well-worn stereotypes so often featured in cinematic and other media portrayals of southern speech do not typify speakers throughout the South. For example, the lack of r after a vowel, once a hallmark of much of the region, is fast disappearing and is increasingly confined to older and African American speakers. The expression y’all, though as trademark a southernism as one can find and routinely acquired by transplants from outside the South, is still replaced by you’uns in some parts of southern Appalachia.

(John L. Hart FLP, and Creators Syndicate, Inc.)

The South has never been a linguistic region unto itself. Nearly all features of English usually ascribed to the region can be found outside the former Confederacy among older-fashioned or rural speakers in one or another part of the country. Neither the Mason-Dixon Line nor any other geographical or political demarcation has ever set off the region linguistically. This became even less the case after World War I as countless African Americans took their southern-derived speech to northern cities in several large waves of migration. Southern English has also been exported abroad from time to time for more than two centuries, by African Americans to Nova Scotia, Sierra Leone, and the Bahamas in the 1780s and 1790s and to Liberia in the 1820s–1850s, and by disaffected whites after the Civil War to Brazil (where their English-speaking descendants are still known as Confederados). (Interestingly, Bahamian English was later brought back to the United States to form a prime constituent of Conch, a variety spoken in the Florida Keys.) The diaspora of southerners thus left its mark on the use of English in several areas overseas.

Early immigrants to the South from Europe were as heterogeneous as migrants to any other region (more so when those from Africa are considered), and into at least the antebellum period the South was no more isolated as a whole than other regions of the United States. Some cosmopolitan types of Southern English, such as those of New Orleans and Charleston, are among the nation’s most recognizable, showing that ethnic mixes and social dynamics often produced distinctive American dialects. These factors were at play even in “isolated” areas. Most Americans, southerners and nonsoutherners alike, tend to view the South as a speech region (perhaps because of its shared history), even though linguistic research can hardly identify common features that definitively mark a “southern accent” or a “southern dialect.”

Although no one common linguistic denominator distinguishes the South, linguists still identify it as a speech region, on the basis of three main characteristics: (1) a unique combination of linguistic features, (2) the use of these features more often and by a wider range of the population than elsewhere in the country, and (3) the consciousness of the people in the South that they form a region with distinctive speechways. These characteristics are clearly interrelated, in that a person’s use of “southern features” can usually be correlated with his or her attachment to the region.

The persistent folk notions alleging distinctive speech in the region often refer vaguely to a “drawl” or “twang” and attribute it to the influence of the hot climate, the slower pace of life, or similar factors. However, the heart of why the region’s speech is distinctive lies in the mundane realms of history, demography, and social factors, on one hand, and in the realm of psychology—in the consciousness of the region’s people—on the other.

Indigenous Languages

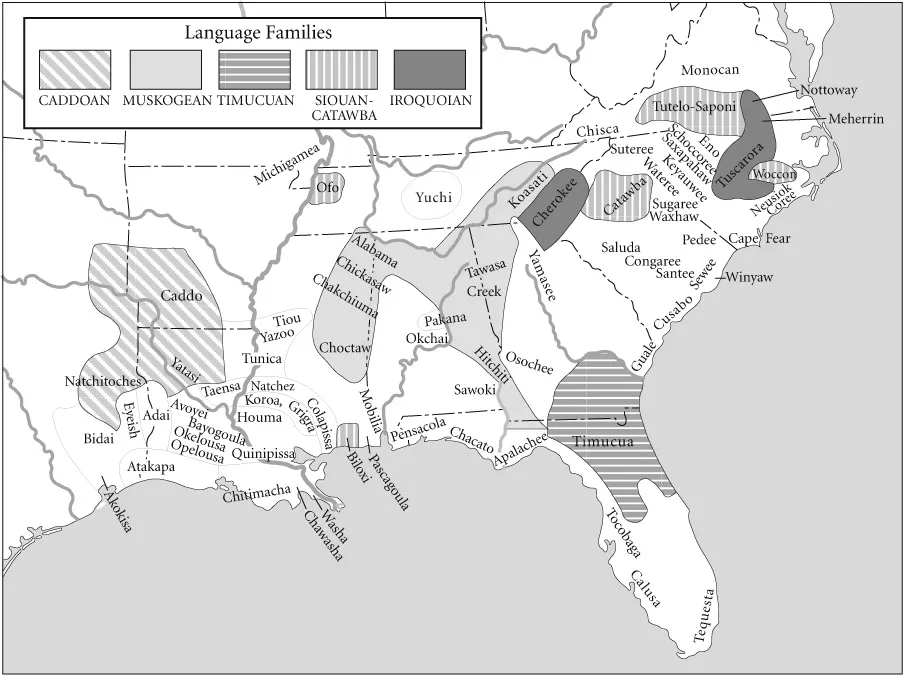

Long before the many varieties of English in the South developed or other European languages arrived, the linguistic landscape of the region was an intricate patchwork of indigenous languages from five important families: Iroquoian, Algonquian, Siouan, Muskogean, and Caddoan. There were also other unaffiliated languages and scattered languages from other families in Texas, making several dozen indigenous tongues in all. Some had been in the region for millennia, but others had arrived in comparatively recent times (e.g., the Biloxi came to Mississippi from what is now the Midwest). Already by the 16th century, contact with the Spanish in Florida and South Carolina had put the existence of many small groups under threat of extinction from forced labor, disease, competition for land, and capture and sale into slavery (a common practice in British colonies into the 18th century). The identity, even the existence, of some tribes and the languages they spoke are known only from a highly fragmentary record that often contains only a few place-names. Though missionaries and other early workers were handicapped in their efforts to analyze languages very different in nearly every way from European ones, having only a Latin-based grammatical framework to base their descriptions on and lacking such tools as a phonetic alphabet, they left behind an impressive record on these languages for later scholars and tribal officials. The literature they produced dates from the early 17th century, when the Spanish and, later, British, French, Americans, and native peoples themselves began collecting word lists, devising systems of spelling, and describing the indigenous languages of the South.

By the beginning of the 21st century all remaining indigenous languages in the South were endangered, as few of them had any native speakers under the age of 20. Extinction of indigenous languages seemed inevitable, abetted by the dominance of English speakers economically, numerically, and politically and by such official policies as the forcible removal in the 19th century of native speakers to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) and prohibition against the use of native languages in tribal schools until recent years. However, revival and revitalization movements have begun sprouting around the region, even where the ancestral language is known only from decades-old recordings (e.g., among the Catawba in South Carolina). Today more courses in tribal languages are offered in schools and community centers than ever before, so their future is by no means so uncertain as it was a few short years ago.

Map 1. Native Languages of the American South

Algonquian and Iroquoian speakers lived in the east. There were several varieties of Algonquian, with Powhatan, spoken in Virginia, being the best-known southern member of the family; it survived until almost 1800. Of the Iroquoian languages, Tuscarora was spoken in eastern North Carolina until 1722, when a remnant of its war-decimated speakers moved to New York, where a handful of older speakers remain on two reservations. Cherokee is still used today in both Oklahoma and among some of the Cherokee who remained behind and now live in western North Carolina. The Cherokee linguist Sequoyah devised a writing system for the language by 1821, bringing rapid literacy to his people; newspapers are still printed using this Cherokee syllabary. The number of Cherokee speakers declined dramatically during the 20th century; but some groups are promoting education in and about the language, and it has for the first time become a required course in a local high school in North Carolina. Speakers of Siouan languages (to which Catawba is distantly related) also lived in Virginia and the Carolinas as well as in Tennessee and Mississippi.

The Muskogean language family, the largest in the region, covered the central portion of the South in present-day Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, northern Florida, and eastern Tennessee in the 19th century. It has nine members: Choctaw, Chickasaw, Alabama, Koasati, Mikasuki, Hitchiti, Creek, Seminole, and Appalachee. Choctaw and Chickasaw are closely related to each other and, like Cherokee, have been written languages since the 19th century; both have current revitalization efforts under way. Hitchiti was a dialect of Mikasuki. Creek and Seminole encompass three mutually intelligible dialects: Oklahoma Creek (also called Muskogee), Oklahoma Seminole, and Florida Seminole. Appalachee, a language originally spoken in the Florida panhandle, became extinct in the early 19th century, but not before the name of the tribe was applied on early Spanish maps to a vague range of mountains in the southern interior, which are today known as the Appalachians. The linguistic diversity of the lower Mississippi Valley led to the creation of a lingua franca known as Mobilian Jargon based on Muskogean vocabulary. It and other Indian trade languages (some of which became pidgins) arose in parts of the South that were particularly heterogeneous or where many groups had contact (as along rivers or seacoasts), in order to facilitate communication and trade between native groups. With between 30 and 60 distinct languages, the American South was a region more linguistically diverse than any other part of North America except California and the Pacific Northwest coast.

Of the Caddoan family, Caddo was the only member in the South, spoken in east Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana. Other indigenous languages have no known relatives, either in the South or elsewhere. Timucua was spoken in northern Florida and southern Georgia; Yuchi is thought to have been spoken in central Tennessee (it survives, but barely, in Oklahoma); Natchez, Tunica, Chitimacha, and Atakapa were spoken in Louisiana and Mississippi.

Beyond east Texas indigenous languages were sparse. Comanche, a member of the Uto-Aztecan language family, was formerly spoken in west Texas and is used now by a small band in Oklahoma. In south Texas there were one or two Apache dialects spoken, primarily Lipan, an Athapaskan language that is now apparently extinct. The seminomadic Kiowa may have gotten as far South as the Texas panhandle on occasion. Beyond these, there were several poorly known languages along the Gulf Coast in east Texas: Karankawa, Tonkawa, Comecrudo, Cotoname, and Atakapa.

The principal linguistic contribution of indigenous languages to English in the South, as elsewhere in the Americas, is in place-names, especially for watercourses (e.g., Tennessee and Yazoo). What they (as well as other languages) gave to regional American English can be judged most accurately and authoritatively from the Dictionary of American Regional English; these borrowings are mainly names for plants. In the dictionary’s first three volumes (encompassing A through O), one finds seven terms from Choctaw (e.g., appaloosa, bayou), three from Cherokee (e.g., conohany), one from Seminole (coontie), and two from Creek (e.g., catalpa). What English has borrowed from native sources in the South is surprisingly modest and obscure, the exception being from Algonquian languages (especially Powhatan or a pidginized form of it) in Virginia, from which John Smith and other early Virginia colonists took opossum, raccoon, persimmon, and other common terms for things novel to Europeans. In western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, and northern Georgia, the Cherokee intermarried with whites and introduced a substantial part of their traditional culture (e.g., their pharmacopoeia) to them, but their linguistic influence was minuscule except for place-names.

Other Non-English Languages

The American South has witnessed nearly five centuries of contact between Old World and New World languages originating on three continents. Speakers of major European languages arrived in permanent settlements in the early 16th century with Spanish in Florida, in the 17th century with English in Virginia and French in Louisiana, and in the 18th century with German in Virginia. In the colonial period these languages were sometimes found more widely than they are today (e.g., Spanish, French, and German in South Carolina). Many other, less prominent languages, such as Ladino (to South Carolina) and Scottish Gaelic (to North Carolina), having fewer speakers and less permanence, came in the 18th century. Immigrant languages have continued to arrive, meaning that the South remains quite a heterogeneous place linguistically and has become eve...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture Volume 5: Language

- Copyright Page

- Epigraph

- CONTENTS

- GENERAL INTRODUCTION

- INTRODUCTION

- LANGUAGE IN THE SOUTH

- INDEX OF CONTRIBUTORS

- INDEX