![]()

1

The Genesis of the Political Ideology of Slavery

Domestic servitude is the policy of our country.

—BRUTUS [Robert J. Turnbull], 1827

By the dawn of the antebellum era, the southern half of the United States had given rise to a distinct slave society. More than any other southern state, South Carolina represented the coming of age of American slavery. As in Virginia, slavery had roots stretching far back to the colonial period, and as in the new southwestern states, the cotton boom of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries made racial slavery an expansive rather than a declining institution. In South Carolina, slavery lay at the heart of a relatively unified plantation economy presided over by a statewide planter class. A majority of the population were slaves, and in no other state did the nonplantation-belt yeomanry lie more at the fringes of slave society.1

On the eve of the nullification crisis, the state’s planter class was poised not only to take over the leadership of the slave South from Virginia but also to formulate a new brand of slavery-based politics that would culminate thirty years later in the creation of the southern Confederacy. They had already played a historic role in the formation of the Constitution as the most articulate and fervent champions of slavery and opponents of democratic measures. Lowcountry South Carolina had been a stronghold of proslavery Federalism in the early republic. The state had long represented a conservative alternative to the republicanism of Virginian slaveholders.2

It was neither periodic bouts of lunacy nor an adherence to the tenets of an archaic republicanism but, rather, the unfolding of the political ideology of slavery during the nullification crisis, that can best explain the sectional extremism of antebellum South Carolina. Despite the establishment of some important precedents during the Missouri crisis and the Hartford convention, the idea of nullification or a state veto of federal law presented the first substantive challenge to the survival of the American republic. Historians have rightly looked to South Carolina for the seeds of southern separatism. However, while they have discussed the emergence of the issue of slavery with the tariff question, they have not sufficiently shown us how slavery affected the very nature of Carolinian political discourse.3 Indeed, some recent historians have argued that nullification had little to do with slavery and that South Carolina’s repudiation of the tariff was an exercise in the defense of republican liberty.4

But Carolinian planter politicians’ attempt to nullify federal tariff laws encompassed a rousing vindication of slavery and the interests of a slave-holding minority in a democratic republic. The Carolina doctrine of nullification was the political expression of a self-conscious and assertive slaveholding planter class that deviated significantly from the republican heritage of the country and the growing democratization of national politics. Couched in the language of states’ rights and constitutionalism, the nullifiers, led by John C. Calhoun, poured new wine into old bottles. They were political innovators. In their rejection of majority rule and democracy and in their aggressive defense of slavery, nullifiers articulated a political ideology that owed its inspiration to the values of a mature slave society.

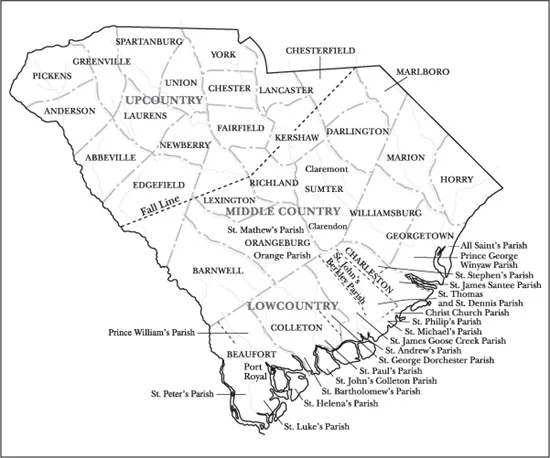

South Carolina’s peculiar social geography allowed its planter politicians to emerge as the spokesmen of a new slavery-centered political discourse. Geographically divided into three broad sections—the lowcountry, the middle country, and the upcountry, which lay above the fall line—the state contained a very small mountainous region; most of its terrain formed no barrier to the spread of plantation agriculture. By the turn of the nineteenth century, with the rise of short-staple cotton cultivation, plantation slavery spread from the lowcountry to the piedmont. This development undermined internecine sectional divisions, which spurred democratic reforms in the rest of the South, and marked the emergence of a new slaveholding elite in the interior. In South Carolina, the non-plantation belt dominated by slaveless yeoman farmers was extremely small and continued to shrink throughout the antebellum era. Significantly, a majority of the Carolinian yeomanry lived in the plantation belt, and many participated in the slave economy as slave owners, slave hirers, overseers, and patrollers. By 1850, the growth of plantation slavery had converted the state into one gigantic black belt. And even though the lowcountry, with its high concentration of slaves, wealth, and large rice and sea island cotton plantations, differed from the rest of the state, South Carolina achieved a unified slave economy and society virtually unique in the South.5

MAP 1. South Carolina Districts and Parishes in 1860

Source: William A. Schaper, “Sectionalism and Representation in South Carolina,” Annual Report of the American Historical Association (Washington, 1900–1901), facing p. 245.

Demographically also, the expansion of slavery and slaveholding made South Carolina a slave state par excellence. The slowing down of the cotton economy in the 1830s and 1840s did not spell the decline of slavery here. Throughout this period the plantation belt continued to grow. South Carolina’s average farm size was the largest in the nation in 1850, even as many small farmers were squeezed out of the state. From 1830 to 1850, the proportion of whites in the state’s population fell, and many more whites migrated out of the state than into it. The slump in the state’s economy would not be relieved until the cotton boom of the 1850s. By mid-century just over 50 percent of Carolinian white families owned slaves; South Carolina became the first southern state to have a slaveholding majority in its white population.6

TABLE 1. South Carolina Population, 1820–1860 |

|

| | White | Black |

| | | |

| Year | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage |

|

| 1820 | 237,440 | 47.2 | 265,301 | 52.8 |

| 1830 | 257,863 | 44.4 | 323,322 | 55.6 |

| 1840 | 259,084 | 43.6 | 335,314 | 56.4 |

| 1850 | 274,563 | 41.1 | 393,944 | 58.9 |

| 1860 | 291,300 | 41.4 | 412,320 | 58.6 |

|

Source: Jullian J. Petty, The Growth and Distribution of Population in South Carolina (Columbia, S.C., 1943), 64.

The number of slaves in the state also grew. In 1810, slaves composed over 80 percent of the total population in most lowcountry parishes, half of the population of most middle districts, and nearly one-third of the population in much of the upcountry. Only the population of the mountain districts of Greenville, Spartanburg, and Pendleton contained less than 20 percent slaves. In 1820, the black population of the state would surpass the white, re-creating its slave majority of the colonial days. On the eve of nullification, black people comprised over 40 percent of the population in a majority of the state’s districts. By 1850, they constituted less than 50 percent of the population in only seven of the state’s twenty-eight districts and they made up around 59 percent of the total population. For every 100 whites in the state there were 140 slaves. Only during the last decade before the Civil War did the black proportion of the state’s population fall slightly. In 1840, South Carolina’s population consisted of 259,084 whites and 335,314 blacks, of whom 327,158 were enslaved and 454 owned slaves themselves. The state’s free black population comprised only around 1 to 2 percent of its population through much of the pre–Civil War period, of whom only a few achieved economic prosperity. An overwhelming majority of black people were enslaved and labored in the swampy rice and sea island cotton plantations and the short-staple cotton fields of the piedmont.7

Slavery, more than any other issue, determined the state’s geopolitics. Carolinian rice aristocrats and the cotton planters from the hinterland formed an intersectional ruling class, bound together by kinship, economic, political, and cultural ties. They presided over the state government and gave birth to the most undemocratic political structure in the Union. South Carolina’s antebellum government was based on its archaic 1790 constitution. An all-powerful, planter-dominated state legislature lay at the heart of a highly centralized system of governance with weak local political organization. Carolinian slaveholders monopolized not only state but also local offices. Legislative apportionment was incredibly lopsided, as the small lowcountry parishes were accorded the same representative weight as the much larger and more populous interior election districts. State representatives were required to have 500 acres and 10 slaves or real estate valued at 150 pounds sterling clear of debt, while state senators had to have a minimum of estate valued at 300 pounds sterling, also clear of debt. An estate of 15,000 pounds sterling clear of debt qualified a citizen for the governorship. Property-holding qualifications for local offices also insured that in South Carolina, as Ralph Wooster notes, “county government remained thoroughly undemocratic.”

The Compromise of 1808, which increased representation for the upcountry, and the 1810 law granting suffrage to most adult white males were enacted after the state was made safe for slavery. The constitutional amendment of 1808 based representation in the house on taxation and population. The amendment increased representation for the interior while keeping intact the entrenched hold of the propertied slaveholding elite on the state government. The 1808 amendment was, as Rachel Klein has argued, an official though belated recognition of the rise of a planter-led slave society in the backcountry. The state senate remained a stronghold of the rotten borough lowcountry parishes. The retention of the parish system and high property qualifications for office holding still gave the lowcountry aristocracy and the planter class as a whole a decisive representative edge in the legislature. In 1810, when all resident, adult, white, male citizens, with the exception of paupers and noncommissioned officers and soldiers of the United States Army, were given the right to vote, the state government was already firmly under the control of the slaveholding planter elite. South Carolina’s antebellum citizenry could exercise its right to vote only in the elections for state legislators and congressional representatives, as state and local officers, the governor, and presidential electors were appointed by the legislature. While voter turnout fluctuated widely, the rate of turnover in the legislature rarely exceeded 50 percent in the antebellum period. Most of the congressional elections were “non-competitive” and “involved no opposing candidates at all.”8

Even those historians who have tried to weave the Old South into an overarching democratic interpretation of American politics were careful to note the exception of South Carolina. The state remained immune to the wave of constitutional reforms that inaugurated Jacksonian democracy in the country. South Carolina was the only state in the Union that did not have a two-party system or popular elections for the presidency, the governorship, and a host of state and local offices. And it retained property and slaveholding qualifications for political office as well as a severely malapportioned legislature until Reconstruction. In the 1850s, Carolinian leaders allowed only a few minor changes to the state’s political system. The upcountry district of Pendleton was divided into two, Pickens and Anderson, and a few local offices were made elective. However, repeated attempts to institute popular elections for governor and for presidential electors and to reapportion the legislature failed.9

Antebellum Carolinian planters’ local stranglehold on state politics went hand in hand with their declining national power. Recent works reveal the highest levels of slaveholding, real and personal property ownership, and planter status among South Carolina state and local officials in comparison to those in the rest of the South. Many prominent planter families such as the Butlers, Mannings, Richardsons, Middletons, Manigaults, Pinckneys, Rutledges, Rhetts, Lowndes, Calhouns, Hamptons, and Smiths retained political power through generations. At the same time, between 1832 and 1842 the state would lose two representatives in Congress, and between 1840 and 1860 its overall congressional representation would fall from nine to six.10 South Carolina’s slaveholding planter class, so potent at home but increasingly impotent in the national arena, would become the foremost spokesmen for southern separatism.

The third decade of the nineteenth century, beginning with the Missouri crisis and ending with the collision between South Carolina and the federal government over the tariffs, was a period of incubation for the politics of slavery. While Carolinian slaveholders had defended slavery since the earliest days of the republic, the emergence of a systematic body of proslavery literature and thought in the state during the 1820s marked the start of a new era. It was not just slavery itself but the tariff issue that ultimately led to the construction of the political ideology of slavery. But slavery transformed a dispute over economic policy into one of unsurpassed sectional bitterness. By the end of the decade, both slavery and the tariff had emerged as points of sectional dispute in the national political arena. It was the fatal intertwining of these two issues in the hands of Carolinian nullifiers by the end of the decade that precipitated nullification.

In the 1820s, Carolinian planter politicians were convinced that internal and external threats endangered slavery. Between the Haitian revolution and Nat Turner’s uprising, the state suffered from a host of slave rebellion scares, including the famous Denmark Vesey conspiracy of 1822. The plot was discovered and put down by such future nullifiers as Robert J. Turnbull, Robert Y. Hayne, and James Hamilton Jr., then the intendant or mayor of Charleston. In response to the Vesey affair, the legislature passed the Negro Seamen’s Act, which interred all black sailors visiting Charleston on the theory that all free black people should be viewed as potential security risks. Passed in defiance of federal treaties and law, this act has been claimed as the first nullification by South Carolina. Despite the disapproval of the federal government, it remained on the statute books until the 1850s and became a model for similar laws in other southern states. Governor John Wilson, a “violent nullifier” and author of a handbook on dueling, defended the act as a “law of self-preservation.” Leading planters formed the South Carolina Association in 1823 to more strictly police slaves and free African Americans. As Edwin C. Holland, an early proslavery pamphleteer, bemoaned, the slaves were the “true Jacobins” and “anarchists” in his state.11

Proposals for emancipation and colonization in the 1820s also evoked a strong reaction in South Carolina, and the state senate warned the federal government against interfering “with the domestic regulations and preservatory measures in respect to that part of her property which forms the colored population of the State.” Whitemarsh Seabrook, pro-slavery writer and nullifier, asked, “Did not the unreflecting zeal of the North and East, and the injudicious speeches on the Missouri question inspire Vesey in his hellish efforts?” The rise of Garrisonian abolitionism seemed to confirm Carolinian slaveholders’ suspicions that northern antislavery feeling encouraged slave resistance. Judge William Harper, second only to John C. Calhoun as a nullification theorist, somberly noted, “It was the ‘Amis des Noirs’ who set on foot the Insurrection at St. Domingo.”12

Slavery, according to Carolinian slaveholders’ construction, was well on its way to becoming the wellspring of southern thought.13 Long before Thomas R. Dew wrote one of the most well-known proslavery tracts in the aftermath of the Virginia slavery debates, Carolinian planters and clergymen produced a slew of proslavery pamphlets in the 1820s. They began defending slavery as the essential and defining element of southern society. Anticipating the main lines of the antebellum proslavery argument, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney argued that slavery was an institution of “Mosaic dispensation” and that it was not “a greater or more unusual evil than befalls the poor in general.” Approving of the destruction of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in the wake of the Vesey conspiracy, Reverends Richard Furman and Frederick Dalcho developed the biblical defense of slavery while pleading for the proper religious instruction of the slaves.14

The Carolinian view of slavery became the justification of a new theory of politics with the rise of the tariff controversy. Besides being the major source of national revenue, tariffs for the protection of infant manufactures were part of an economic program resurrected after the 1812 war in Henry Clay’s American system. The system included the establishment of a national bank and internal improvement projects. The only detractors, at this point, were a group of southern conservatives led by John Randolph of Virginia and younger states’ rights men such as William H. Crawford of Georgia and his ally, William Smith of South Carolina. In 1825, under Smith’s guidance, the South Carolina legislature passed resolutions declaring the system of internal improvements and the tariff unconstitutional. Calhoun and William Lowndes, both of whom had begun their careers as War Hawks, led the dominant nationalist group against the states’ rights Smith faction. The ardent George McDuffie, whose only fault according to unionist Benjamin F. Perry was that he allowed his mentor, Calhoun, to dictate his public course, went so far as to declare states’ rights the refuge of ambitious and less talented men who could not make their mark in national politics. But even as McDuffie put his view of states’ rights to the test of a bullet in a series of duels with an offended Geor...