![]()

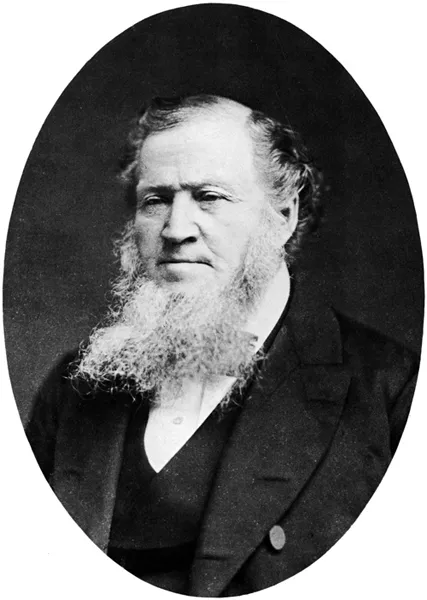

1 Brigham Young’s Romance with American Higher Education, 1867–1877

In the 1860s, Mormons began knocking at the doors of American colleges and universities. Reversing the course of their westward-bound pioneer ancestors, these academic emigrants sought to retrieve what their forerunners had left behind, by force or by choice: their access to higher education. By 1940, hundreds of Mormons had left Utah and Idaho to study “abroad” in the elite universities of the United States. In the earliest cases, church leaders sent the students as missionaries, but not to proselytize. Rather, they tapped these women and men for specialized training in professions ranging from law, medicine, and engineering to education. Mormons saw education in “Gentile” universities as a means to realize a corporate hope: a kingdom of God in the Mountain West. The goal was, in the words of Brigham Young, to gather the world’s knowledge to Zion, to help build the perfect society in the “latter days” before God’s millennial reign.

Religious and secular motives drove the students’ migration. Mormons had long believed that education hastened their spiritual progression toward godhood. Before his assassination in 1844, Joseph Smith had taught that “the glory of God is intelligence” and instructed believers to “study and learn, and become acquainted with all good books, and with languages, tongues, and people.”1 The impulse to learn intensified, however, in the 1870s, when the completion of the transcontinental railroad forced Utah Mormons to adopt new strategies for maintaining their cultural and economic independence. Higher education was no longer just a means of spiritual progress; it was also a way to survive. In the mind of Brigham Young, sending women and men “abroad” to receive advanced degrees would reduce the church’s dependence on outside doctors, lawyers, and teachers, preserving Mormons’ dignity and strength.

The first Mormon to venture east for training in the professions appears to have been Elvira Stevens Barney, who left Utah in 1864 to spend nearly two years studying medicine at Illinois’s Wheaton College.2 Mormon academic migration would not become a movement, however, until it had the explicit sanction of Young, the church’s president and prophet. Earlier in his administration, he had made important practical and theological arguments in support of education. In 1859, for example, he had urged the Saints to go forth and gather the best of the world’s knowledge, to build the perfect society. He affirmed that “it is the business of the Elders of this Church … to gather up all the truths in the world pertaining to life and salvation, to the Gospel we preach, to mechanism of every kind, to the sciences, and to philosophy, wherever it may be found in every nation, kindred, tongue, and people and bring it to Zion.”3 Later, in 1860, Young proclaimed that “intelligent beings are organized to become Gods, even the Sons of God, to dwell in the presence of the Gods, and become associated with the highest intelligencies [sic] that dwell in eternity. We are now in the school, and must practice upon what we receive.”4 The rewards of education were great, here and in the hereafter.

Young was not especially inclined, however, to promote a large-scale academic migration. In 1866, he told a Mormon correspondent that “going abroad to obtain schooling will be labor spent in vain.”5 Such study would be costly and unnecessary, Young argued, since Utah boasted well-trained teachers in virtually all branches of learning. At best, the claim was debatable; opportunities for higher education in Utah virtually did not exist.6 The distortion revealed Young’s reluctance to endorse education abroad unless it met the urgent needs of the Mormon kingdom.

Authorizing Mormon Study “Abroad”

Pressing concerns about the welfare of the Saints finally prompted Young to approve a limited student migration in 1867. He knew that his developing territory desperately needed trained surgeons, especially in the fledgling settlements north of Salt Lake City. Yet Young hoped that after just one or two students received their eastern degrees, they could train others back home and eliminate the need for additional outside training. Mormon independence was paramount.7

Young also harbored suspicions of the medical profession itself. Mormon scripture justified that skepticism, with its abundant testimony to the healing power of faith. Teachings revealed in the Doctrine and Covenants, the collection of modern revelations given mainly to Joseph Smith, convinced Mormons that their elders could heal the sick through the laying on of hands. In cases where the patient could not muster the requisite faith, Smith forbade medical care at “the hand of an enemy,” prescribing only “herbs and mild food” as treatment.8 These attitudes toward healing and the medical profession led Brigham Young to allow Mormons to study surgery, but not medicine. He contended that “surgery will be much more useful in our Territory than the practice of medicine, [because] simple remedies such as herbs and mild drinks are in operation in our faith, and it is my opinion that too many of our people run to the doctor if they experience the slightest indisposition, which is decidedly opposed to the revelation which governs us as a people.”9 Young tried to ensure that when he endorsed academic training abroad, he would not lead the faithful to question the sufficiency of revelation or faith. He was walking a tightrope.

Brigham Young first authorized Mormon study “abroad” in the 1860s. Used by permission, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo.

With Young’s blessing, the first Mormon to train in surgery was Heber John Richards, a twenty-seven-year-old elder living in Salt Lake City. In 1867, Young arranged for Richards to study under Dr. Lewis A. Sayre at the Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City. Young had met Sayre the previous year in Salt Lake City, and the Mormon leader recognized in him a wealth of knowledge that “could not perhaps be excelled on this continent.”10 When Sayre offered to train one or two Latter-day Saint students in surgery at Bellevue, Young encouraged Richards to go.11 In November 1867, Richards left for New York.

Given the financial support and the blessing of the church, Richards understood his academic errand as a mission.12 Although the prophet did not expect Richards to devote much time to securing converts, he nevertheless wanted Richards to see his studies as a sacred calling. Young instructed him to pursue his course of study diligently, ever mindful that “you hold the priesthood.” To help reinforce Richards’s religious commitments, the prophet prescribed regular meetings with other Saints in New York; preaching to the inhabitants of the city whenever possible; and, when among non-Mormons at school, association only with “those of steady and virtuous habits.” Young offered his admonitions to fortify Richards for his time in “the world.”13

A more formal, ritualized blessing accompanied the prophet’s personal advice. In keeping with Mormon rites established to consecrate a missionary for labors in the world, Elder John Taylor (who would eventually succeed Young as president of the church) “sealed” a blessing upon Richards: “[W]e pray God the Eternal Father to cause His holy spirit to rest down upon you that your mind may be expanded that you may be able to understand correct principles, that the blessings of the Most High God may be with you, that the spirit of inspiration may rest upon you while you are studying those principles to which you have been appointed[.]”14 Richards left Salt Lake City armed with the blessings of God, God’s prophet, and God’s holy priesthood. He planned to return with uncorrupted faith and acquired expertise.

Richards’s academic and spiritual success mattered to the Saints at home. In their eyes, New York was a dark, lost city of “Babylon,” a place of spiritual darkness and omnipresent vice, a proving ground for the righteous. At the same time, paradoxically, many admired New York as a center of culture and refinement. They eagerly awaited news of Richards’s exploits. Reports occasionally came in from David M. Stewart, a Mormon in the missionary field. In 1868, Stewart gave the following news: “Br. Heber John Richards writes me … occasionally. He says he is … preaching the gospel every opportunity that offers. He is hale in body, cheerful in spirit, but says in conclusion, ‘there is no place like home.’ ”15 In early 1869, Stewart visited Richards and filed another report: “We spent a very interesting day with Bro. Heber John Richards in New York, and we saw sights never to be forgotten in the ‘Bellvue [sic] Medical College,’ and other places of interest. He is rapidly improving in the study of anatomy, and treasuring up classic lore, which if properly applied will be of great benefit to its possessor.”16 Such accounts reassured and flattered the faithful at home. Richards eventually returned to Salt Lake City with his degree from Bellevue. He had a successful practice in Salt Lake until 1892, when he moved south to Provo and practiced there until his retirement.17

By 1869, the importance of sending Mormon students “abroad” became even more apparent in an increasingly diverse, modernizing Utah territory. The transcontinental railroad, which Young famously welcomed because it would hasten the gathering of Mormon converts to Zion,18 nevertheless introduced unwelcome competition in the realms of business, law, politics, religion, and education. To ensure that he had lawyers to ward off Gentile attacks on his financial holdings, doctors to administer healing to the suffering, and engineers to build the infrastructures of Zion, Young began to consider sending some of his own children east on educational missions. As most contemporary Americans knew, he had dozens from whom to choose.19

The first to go east in the 1870s was Willard Young, born in 1852, Brigham’s third child by Clarissa Ross Young. Brigham thought his bright, strong son was well suited for an educational mission to a fortress of American patriotism and strength: West Point. (As governor of the Utah territory, it was Brigham’s prerogative to choose a representative from the territory to attend the New York military academy.) Brigham knew that Willard would not only receive a first-rate, “practical” education there, but also enjoy a rare opportunity to demonstrate that Mormons were as rational and civilized as other Americans.

To help strengthen Willard for his time in “Babylon,” Brigham had him, like Heber John Richards, blessed and “set apart” as a missionary by members of the church’s First Presidency. The church’s highest-ranking authorities prayed over Willard that he might “go and fulfill this high and holy calling and gain this useful knowledge, and through the light of truth, make it subservient for the building up of the Kingdom of God.”20 Just after Willard arrived in New York, the prophet wrote with additional assurances (“our prayers are constantly exercised in your behalf”) and warnings (“the eyes of many are upon you”).21

By December of his first academic year (1871–72), Willard had good news to report. He felt that the blessings the brethren placed upon him were coming to fulfillment. “I am succeeding quite well in my studies, and I never enjoyed more the spirit of our religion,” he avowed. He marveled at the effect he seemed to be having on other cadets, whose anti-Mormon sentiment had waned. Some of his non-Mormon peers, he said, now even went so far as to say that aggressive anti-polygamists were “entirely wrong.”22

Again, the Saints at home took special notice of how their representative was faring in the eyes of the world. When Willard was interviewed by a curious New York reporter, Salt Lake City’s pro-Mormon newspaper, The Deseret News, reprinted the exchange in full. With equal insecurity and pride, the Salt Lake editors noted that the interviewer “evidently found the young gentleman, though a resident of these mountains from birth until now, well prepared to answer his questions.”23 Home pride swelled again when Cadet Young graduated in 1875, fourth in his class of forty-three, and was promoted to the Corps of Engineers. The Deseret Evening News opined that Willard had vindicated Mormonism and polygamy:

The success of Utah’s first West Point cadet further confirms the erroneousness of the idea that the minds of polygamous children are inferior to those of monogami...