- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Boundaries of American Political Culture in the Civil War Era

About this book

Did preoccupations with family and work crowd out interest in politics in the nineteenth century, as some have argued? Arguing that social historians have gone too far in concluding that Americans were not deeply engaged in public life and that political historians have gone too far in asserting that politics informed all of Americans' lives, Mark Neely seeks to gauge the importance of politics for ordinary people in the Civil War era.

Looking beyond the usual markers of political activity, Neely sifts through the political bric-a-brac of the era — lithographs and engravings of political heroes, campaign buttons, songsters filled with political lyrics, photo albums, newspapers, and political cartoons. In each of four chapters, he examines a different sphere — the home, the workplace, the gentlemen’s Union League Club, and the minstrel stage — where political engagement was expressed in material culture. Neely acknowledges that there were boundaries to political life, however. But as his investigation shows, political expression permeated the public and private realms of Civil War America.

Looking beyond the usual markers of political activity, Neely sifts through the political bric-a-brac of the era — lithographs and engravings of political heroes, campaign buttons, songsters filled with political lyrics, photo albums, newspapers, and political cartoons. In each of four chapters, he examines a different sphere — the home, the workplace, the gentlemen’s Union League Club, and the minstrel stage — where political engagement was expressed in material culture. Neely acknowledges that there were boundaries to political life, however. But as his investigation shows, political expression permeated the public and private realms of Civil War America.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Boundaries of American Political Culture in the Civil War Era by Mark E. Neely Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1: Household Gods Material Culture, the Home, and the Boundaries of Engagement with Politics

Before the Civil War, the poet Walt Whitman was a beer-swigging Bohemian, but when the war came he finagled himself an easy patronage job in Washington, D.C., and in the abundant spare time provided by that sinecure, he transformed himself into a saint. Instead of patronizing saloons at night as he had done customarily in Brooklyn, he left work early each day in Washington to visit the wounded in Union hospitals. He watched pus run out of wounds and wretched men vomit and waste away with dysentery. After a while, he took a leave to go back to Brooklyn, to visit his old pals from his Bohemian days, and to vote. It was the election summer of 1864.

When he got to Brooklyn, Whitman discovered that he had changed. He did paint the town once again, but he now felt different about nightlife:

Last night I was with some of my friends . . . till late wandering the east side of the City—first in the lager bier saloons & then elsewhere—one crowded, low, most degraded place we went, a poor blear-eyed girl [was] bringing beer. I saw her with a McClellan medal on her breast—I called her & asked her if the other girls there were for McClellan too—she said yes every one of them, & that they wouldn’t tolerate a girl in the place who was not, & the fellows were too—(there must have been twenty girls, sad ruins)—it was one of those places where the air is full of the scent of low thievery, foul play, & prostitution gangrened—1

Whitman had undergone a profound change in point of view. His old Bohemian life now seemed diseased and immoral, whereas his new life, spent in Washington with real disease and gangrene, seemed elevated by national self-sacrifice.

A political historian cannot help noticing the importance of voting to the Whitman anecdote. The pains the poet took to get home to vote made the scene possible. Whitman was a peculiarly lucky beneficiary of the political system as a patronage officeholder, but casting a ballot was a persistent habit for many others who qualified to vote in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Whitman’s letter also offers readers a rare glimpse of lower-class political culture—with a surprising gender twist in the bargain. The path to arriving at this image of political engagement in 1864 turns out to be the low and neglected one of material culture: had the barmaid not been wearing a McClellan political button, this rich election summer vignette would never have been recorded.

Walt Whitman voted regularly and the barmaids in Brooklyn wore Democratic campaign medals because politics engaged the attention and enlisted the emotions of vast numbers of Americans in the mid-nineteenth century. Political history in universities has fallen on hard times in recent years, but it has clung tightly to its claim that politics mattered immensely to Americans then—in fact, that the percentage of voter participation from the 1840s to the 1890s has not been equalled or surpassed before or since. Glenn C. Altschuler and Stuart M. Blumin’s Rude Republic: Americans and Their Politics in the Nineteenth Century thus took aim at the principal claim made for the importance of American political history in the nineteenth century, namely, people’s unparalleled level of involvement in political activities.

The solid foundation of that old claim, not denied by Altschuler and Blumin, was behavioral. It rested firmly on deeds and not mere words: in the period 1840–96 national voter turnout averaged 78 percent in presidential elections, according to historian Joel H. Silbey. The 78 percent represents an average for all the states lumped together. Statistics from individual states could be even more impressive. Between 1840 and 1892 voter turnout in presidential elections in New York state, Silbey points out, was 88.6 percent.2

The statistics on nineteenth-century voter turnout remain to this day the bedrock of the modern analysis of American politics in that period. But that remarkable level of engagement can be irrefragably documented on election day only, and what happened in people’s lives in the long stretches between elections is difficult to get at—hence the modern debate over the level of nineteenth-century Americans’ engagement in politics.

For some historians, those voting statistics have provided the foundation of a view of the wider American culture in Abraham Lincoln’s era. In a famous article, historian William E. Gienapp invoked a quotation from a journalist covering the 1860 presidential campaign as the title of the piece and the epitome of the times: “Politics Seem to Enter into Everything.” “More than in any subsequent era,” Gienapp contended, “political life formed the very essence of the pre–Civil War generation’s experience.”3 In a later book on the origins of the Republican Party in the 1850s, Gienapp described the political culture of the era in these words: “Individuals viewed events, facts, and observations through the prism of party identity.”4 That idea has been echoed by political historian Michael E. McGerr, who describes the political party of the nineteenth century as “a natural lens through which to view the world.”5

Eager to make the best case for our subject, political historians such as McGerr, Silbey, Gienapp, and me have embroidered the hard voting statistics with anecdotal descriptions of the great torchlit parades, barbecues, fireworks displays, and mass political rallies that offered nineteenth-century Americans the time-filling amusement later provided by sport, the ritual provided by state religions in Europe, and the spectacle (minus a great ceremonial military presence) offered by the powerful central governments of monarchical and aristocratic countries.6

The authors of Rude Republic are justifiably suspicious of claims that the nineteenth century constituted a golden age of “vibrant” and “young” democracy in which there was an unequalled level of political engagement on the part of individual Americans. On the contrary, Altschuler and Blumin argue essentially that the activities of election day constituted an anomaly, an interruption in family and workaday lives. To these social historians, the salient characteristic of the seasons of party activity was their brevity. The periods of election enthusiasm, they say, were the products of feverish attempts by a dedicated but small core of political activists to use every available technique to cajole and nudge and persuade and stampede and hornswoggle an American populace that was generally indifferent to politics and suspicious of political parties—to drive them to the polls for a brief moment of political engagement. The high level of party organizational activity, in this new point of view, proves only how difficult it was to make Americans care about politics and to overcome their natural distaste for politicians. Americans retained suspicions that such ambitious men were not to be trusted with the welfare of the republic. Electioneering and its apparatus were, for the authors of Rude Republic, “the efforts of those who were deeply involved in political affairs to reach and influence those who were not. The very intensity of this ‘partisan imperative’ suggests the magnitude of the task party activists perceived and set out to perform.”7

Altschuler and Blumin assert “the primacy of the community” as against “the proper limits of partisan conflict.” They discern in nineteenth-century American society a “carefully constructed boundary between politics and other communal institutions—the church, the school, the lyceum, the nonpartisan citizens’ meeting.” At bottom they posit a well-defined and hierarchical separation between home and the public realm. They believe that the worldview of the mass of middle-class Americans can be described as “vernacular liberalism,” defined this way:

It is no more than unreflective absorption in the daily routines of work, family, and social life, those private and communal domains that the small governments of the era hardly touched. . . . We suspect that the radical disconnectedness and “privatism” observed in America by Tocqueville and other European visitors in this period translated in many instances into a primacy of self and family that confined politics to a lower order of personal commitment than is generally recognized. Tocqueville himself argued that Americans were passionately interested in politics, but he would not have seen much or many of those people to whom we refer. Neither have many historians ferreted them out from their chimney corners and workbenches. Most Americans did vote, and for many historians that has been enough. We would look more closely at “liberalism,” not merely as a political theory, but also, for some, as an apolitical way of life.8

Such “apolitical” people would stand as the polar opposites of those, described by Gienapp and other political historians, who saw the nineteenth-century world through the lens of party political affiliations. The argument reaches to the most profound assumptions not only about political history but about the very nature of the “people.”

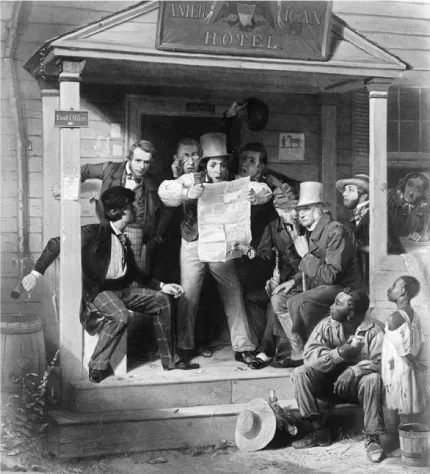

And yet, there is abundant evidence that there was more to nineteenth-century political commitment in America than a quadrennial trip to the polls. The evidence is under our very noses and constitutes one of the principal sources of information relied upon by the authors of Rude Republic for reaching contrary conclusions: the daily and weekly press. The American absorption in newspapers caught the attention of nearly everyone at the time—from genre painters (see Fig. 1.1) to census takers. Joseph C. G. Kennedy, the head of the census bureau, pointed out that the 1860 census “strikingly illustrates the fact that the people of the United States are peculiarly ‘a newspaper-reading nation,’ and serves to show how large a portion of their reading is political. Of 4,051 papers and periodicals published in the United States . . . three thousand two hundred and forty-two, or 80.02 per cent., were political in their character.”9

Newspapers had doubled in number since 1850, far exceeding the increase in population in the decade. The papers were functions of politicization rather than urbanization. Only 126 communities in the United States in 1860 had a population exceeding 3,200 people. The 3,242 political newspapers, then, must have blanketed the myriad small towns and villages across the land. Illinois provides a good example. The census of 1860 found 259 political newspapers in the state, which contained only 133 towns with populations exceeding 1,500. It follows that nearly every town of 1,500 enjoyed the circulation of two political newspapers, one for each major party, the typical pattern.10 These papers owed their existence, in small communities and large, to the sustained nature of the American involvement in politics.

FIGURE 1.1. Mexican News. Engraving by Alfred Jones, after painting by Richard Caton Woodville (1853). Reproduced from the Collections of the Library of Congress. The centrality of the newspaper to this genre scene suggests the importance of that essentially political medium to men, women, and children of different ages, social classes, and races.

The editors almost literally redoubled their efforts in election season, producing special campaign editions of the regular newspaper. The periods of intensive electioneering to which Rude Republic refers were thus marked by the appearance of still more newspapers specially got up for the presidential election seasons. These campaign papers came atop the weekly and daily drumbeat of political agitation that appeared steadily, year in and year out.

The Whig Party of Illinois provided examples. In its earliest organization, the founding of daily and weekly newspapers was essential. A press was what a party organization needed most. The proliferation of party newspapers in Illinois was remarkable. Before the end of the decade of the 1840s, even Little Fort, Illinois (later renamed Waukegan), sported the Whig Lake County Visitor to oppose the Porcupine and Democratic Banner. The ambitious Whig campaign for the presidency in 1840—the fabled “log cabin and hard cider” campaign—saw the Whigs of Springfield, the state capital, bring forth the Old Soldier (the “old soldier” was the Whig candidate for president, General William Henry Harrison). Eighteen issues of the campaign newspaper appeared between February and November 1840. The Old Soldier had its Democratic counterpart, the Old Hickory.11

The Whig Party of Illinois was relatively feeble. It never managed to elect a governor or senator. But Illinois Whigs were capable of strenuous electioneering. In addition to the Old Soldier in 1840, the Whig State Central Committee published seven issues of the Extra Journal for the important 1843 elections in the state, contests for the U.S. House of Representatives in seven congressional districts (for which the Illinois Whigs put forward candidates in only six).12 The existence of the Extra Journal reminds us of the important point made by the historian Roy F. Nichols years ago that the election calendar of the nineteenth century did not really allow fallow “off years.” The states established the election calendar, and important elections occurred over a broad range of times stretching from March to November and in odd and even years alike.13

The newspapers that provided the authors of Rude Republic with the names of the small core of activists who regularly attended party organizational meetings and caucuses were steady presences both in election season and out. The steady readership could not have been small. These newspapers bore witness daily or weekly, year in and year out, to the perennial interest of many Americans in political life. How else but through the amazing existence of these party newspapers could Altschuler and Blumin base their study i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Boundaries of American Political Culture in the Civil War Era

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Household Gods Material Culture, the Home, and the Boundaries of Engagement with Politics

- Chapter 2: A New and Profitable Branch of Trade Beyond the Boundaries of Respectability?

- Chapter 3: A Secret Fund The Union League, Patriotism, and the Boundaries of Social Class

- Chapter 4: Minstrelsy, Race, and the Boundaries of American Political Culture

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index