- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Black Politics in New Deal Atlanta

About this book

When Franklin Roosevelt was elected president in 1932, Atlanta had the South’s largest population of college-educated African Americans. The dictates of Jim Crow meant that these men and women were almost entirely excluded from public life, but as Karen Ferguson demonstrates, Roosevelt’s New Deal opened unprecedented opportunities for black Atlantans struggling to achieve full citizenship.

Black reformers, often working within federal agencies as social workers and administrators, saw the inclusion of African Americans in New Deal social welfare programs as a chance to prepare black Atlantans to take their rightful place in the political and social mainstream. They also worked to build a constituency they could mobilize for civil rights, in the process facilitating a shift from elite reform to the mass mobilization that marked the postwar black freedom struggle.

Although these reformers' efforts were an essential prelude to civil rights activism, Ferguson argues that they also had lasting negative repercussions, embedded as they were in the politics of respectability. By attempting to impose bourgeois behavioral standards on the black community, elite reformers stratified it into those they determined deserving to participate in federal social welfare programs and those they consigned to remain at the margins of civic life.

Black reformers, often working within federal agencies as social workers and administrators, saw the inclusion of African Americans in New Deal social welfare programs as a chance to prepare black Atlantans to take their rightful place in the political and social mainstream. They also worked to build a constituency they could mobilize for civil rights, in the process facilitating a shift from elite reform to the mass mobilization that marked the postwar black freedom struggle.

Although these reformers' efforts were an essential prelude to civil rights activism, Ferguson argues that they also had lasting negative repercussions, embedded as they were in the politics of respectability. By attempting to impose bourgeois behavioral standards on the black community, elite reformers stratified it into those they determined deserving to participate in federal social welfare programs and those they consigned to remain at the margins of civic life.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I Life at the Margins

CHAPTER 1 The Wheel within a Wheel

Black Atlanta and the Reform Elite

In 1933, at the very dawning of the New Deal, the Neighborhood Union (NU), black Atlanta's preeminent voluntary social-work agency, commemorated its twenty-fifth anniversary by looking back. Celebrating its founder, Lugenia Burns Hope, the NU produced a pageant highlighting the inspiration that led her to create the settlement-work organization. According to NU legend, in 1908 an invalid woman living on Atlanta's west side died needlessly after being neglected by her neighbors, who knew nothing of her or her illness. This woman lived in the shadow of Atlanta Baptist (later Morehouse) College, where Hope's husband, John, was then president. Hope, an experienced social worker who had trained at Hull House in Chicago and worked for years for the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA), was appalled that this incident could take place in her neighborhood. Brooding, the pageant portrayed Hope looking down at the black neighborhoods that surrounded the hills of the campus, a broad cross-section of Atlanta's black community, including “large beautiful dwellings, humble cottages, rich and poor, learned and ignorant, block after block.”1 She wondered about these neighbors, asking, “How did they fare? Who suffered? What were their ambitions? What were their problems?”2 From these questions a desire began to burn inside her “for a more neighborly understanding” in the black community, “to have the strong help hear the infirmities of the weak, to have the learned share their learning and culture in re-creating the environment of the unlearned, to have the rich share (at least in idea and ideals) their bounties with the poor.”3

The NU'S founding story perfectly evokes Du Bois's “wheel within a wheel,” of a community united by the forces of segregation to which all its members were subjected, yet as socially, economically, and culturally diverse as the white city that confined black Atlanta from without. Hope's ability to see the full scope of the African American community from her lofty perch and her identification with all she observed attests to the common experiences of every African American in a Jim Crow city. However, her questions about the lives of her neighbors and the elitism of her reform vision suggest the social distances that needed to be breached in order to accomplish her vision of racial solidarity. Understanding Hope's perspective and black Atlanta's history in the quarter century leading up to the New Deal sets the stage for what would transpire in the decade to come.

The twenty-five years commemorated by the Neighborhood Union also represented the quarter century in which the Jim Crow system achieved its greatest institutionalization and stability in Atlanta. From the vicious riot of 1906, marking the triumph of white supremacy in the city, to the beginning of the New Deal, black Atlantans were trapped behind a white-imposed bulwark of segregation with few opportunities for escape. The “Gate City” that white boosters liked to promote as the South's most modern and progressive place, was also one of the region's most repressive cities for African Americans, whom whites managed to exclude from a burgeoning industrial economy and to consign to a paternalistic and exploitative order. In fact, as historian Tera Hunter has noted, “modernization and Jim Crow grew to maturity together” in Atlanta, where “each adoption of advanced technology or each articulation of platitudes of progress” strengthened a “commitment to keeping blacks subordinate and unequal.”4

The Atlanta riot, a five-day orgy of white violence against the city's black community, marked Jim Crow's victory. Raised to fury by the gubernatorial campaigns of Hoke Smith and Clark Howell, both of whom raised the specter of “Negro domination” in their election speeches, white Atlantans sought to purge the city of black influence in a period when African American upward mobility, migration to the city, and potential political power threatened white supremacy. The targets of white violence during the riot pointed to these white fears. The assaults began on Decatur Street, the city's most infamous vice district, with the vigilantes in search of the black “rapists,” whom Atlanta's pernicious yellow press and Hoke Smith's campaign claimed roamed the city's streets seeking white victims. Then the mob moved the short distance to the central business district, where it first sought out prosperous black businesses catering to whites, destroying their property and attacking their employees, and then moved on indiscriminately to attack any African Americans they could find in the area, sometimes even dragging black passengers off of streetcars passing through. Finally the crowd moved into black neighborhoods, both poverty-stricken downtown neighborhoods and relatively prosperous enclaves such as Brownsville in south Atlanta, torching houses and vowing to “clean out the niggers.”5 At least twenty-five black Atlantans were killed in the riot, with hundreds seriously wounded or left homeless.6

The Atlanta riot attested to whites’ determination to suppress or destroy any possibility of black equality with whites, whether “social” or economic, and to move African Americans once and for all beyond the pale of civic life, where white Atlantans believed they belonged. The riot was meant to show black residents that they had no claim on public space and no legitimate place in the city's economy except as the dependent employees of paternalistic and exploitative white employers. To entrench their position after the terror, white Atlantans enforced an increasingly rigid color line, threatening the resumption of violence against any African American who dared break it. This was the white-imposed order that bound together all black Atlantans on the eve of the New Deal.

By the early 1930s, Jim Crow's consolidation meant that black and white Atlantans lived more separately than ever before. Where the two groups had once lived in a checkerboard pattern throughout the city, now African Americans lived in solidly black enclaves behind a rigid color line. If these overcrowded black neighborhoods overflowed into white districts, racial violence always ensued, with residents defending the “whiteness” of their communities by attacking their new black neighbors or stoning the windows or dynamiting the porches of their homes. Where once the most prominent black-owned businesses catered to a white clientele in the city's central business district, now black entrepreneurs’ only opportunities lay in serving the African American community. As this segregation suggests, African Americans were treated as unwelcome and temporary interlopers outside of their own neighborhoods. They could make no claim to the city's “white” public space.

The only truly legitimate place in the white city for black Atlantans was as workers under the protection and authority of a white employer. The root of black Atlantans’ isolation from the social and political mainstream lay in their occupational and economic segregation. Like African Americans around the country, black Atlantans faced extremely limited vocational opportunities. Outside of the black economy, they were only permitted to perform those jobs deemed “Negro work” by whites. The vast majority of these occupations were closely related to the work blacks had performed in slavery, and constituted the hardest, dirtiest, and most menial jobs. These occupations were so poorly paid that many families required more than one wage-earner to survive. Consequently, over 57 percent of black women and girls over the age of ten participated in the work force in Atlanta in 1930, almost twice the rate of white women.7

The occupational category that most exemplified “Negro work” was domestic and personal service. In 1930, 58 percent of all gainfully employed black Atlantans, and almost 90 percent of employed women served whites as maids, cooks, in-home and commercial laundry workers, janitors, bellmen, porters, and waiters. They worked in hotels, office buildings, railroad stations, commercial laundries, and in private homes. African Americans filled almost all service positions in the city. For example, of the 13, 245 female house servants in Atlanta in 1930, only 265, or 2 percent, were white.8

While almost 80 percent of black women workers labored outside the commercial or industrial work place as domestic workers in private homes, only about 7 percent of black men did so. They had more choice when it came to their place of work, if not the kind of work they performed. Just fewer than three-quarters worked in manufacturing, in Atlanta's important transportation and communication industries, and in trade. Yet aside from constituting a significant minority of the total number of skilled construction workers, and a majority of tailors, locomotive firemen and mail carriers in the city, black men in these industries were consigned almost entirely to work as unskilled laborers. This labor category constituted the most physically demanding and dangerous work in the city, as well as the most insecure. Unlike black women, who could almost always find some kind of domestic work, black men often were part of the surplus industrial labor force, subject to frequent layoffs, and unable to find steady, let alone permanent, work.9 (See Appendix, Table 2.)

Although Atlanta had a large population of high school or college-educated African Americans, this group was never considered for white-collar work in the white community. Similarly, black Atlantans were almost entirely excluded from any kind of modern mechanical work in the city's prosperous railroad yards, textile mills, and steel factories. Black men working in this sector were almost never permitted to operate machinery as operatives, machinists, or mechanics, work that was automatically defined as “white.” The only skilled occupations that blacks were permitted to practice were the “trowel trades”—brickmasonry, plastering, painting, and carpentry—crafts with which African Americans had been associated historically and which did not involve mechanical work. Racial custom was entrenched into local labor relations by the politically powerful Atlanta Federation of Trades, most of whose craft union members banned blacks outright, making it impossible for African Americans to learn a craft through a union apprenticeship, let alone practice it, and making it difficult for skilled black tradesmen, such as brickmasons, to find work on construction sites.

Many black men and most black women did not participate in Atlanta's white commercial or industrial economy in any way. Instead, they worked in private homes, where their work most closely mimicked the premodern paternalism, coercion, and exploitation of slavery. Low wages made domestic work's ubiquity possible. In the 1930s, most female domestic workers in Atlanta earned six dollars or less for a seven-day work week in which they were expected to work twelve or more hours a day, except for an afternoon off on Thursday. Given that in 1930 almost a third of black households in Atlanta were headed by women, many of which included children, thousands of black women in Atlanta were forced to support their families on less than a dollar a day.10

Along with residential and occupational segregation, black Atlantans were subordinated through their exclusion from politics. The 1906 election that provoked the Atlanta riot was also the one that cemented black disfranchisement in Georgia. Like African Americans across the South, black Atlantans were barred from voting in the white Democratic primary, the crucial election for choosing all public Officials in the region. And while they could cast ballots in general and “special” elections for municipal bond issues, the recall of public Officials, and plebiscites on issues like Prohibition, voter registration was contingent on the payment of a one-dollar, cumulative poll tax, which kept all but a few hundred black Atlantans from registering by 1930. Without the power to participate in the electoral process, the black community could not extract support from local politicians or Officials. Instead, these whites could ignore African Americans or turn against them to curry favor from their white constituencies, as Howell and Smith had, with brutal results, in 1906.11

The condition of the neighborhoods in which black Atlantans had to live was the most visible manifestation of their noncitizenship in the city. Black Atlantans lived in neighborhoods largely bereft of city services such as electricity or sewers. The city neglected to collect garbage in black neighborhoods except sporadically yet located at least five municipal dumps in the African American community, including two adjacent to those most venerable of black Atlanta's institutions, the colleges. Many black Atlantans lived in neighborhoods tolerated by city Officials as de facto vice districts where corrupt police allowed large-scale bootlegging operations and prostitution to prosper, for a cut of the profits. In all black neighborhoods the police acted with unchecked brutality, arresting people at will for no other reason than loitering. They often beat and even sometimes killed those who resisted such specious arrests. In short, black Atlantans, even if they resided in the middle-class enclaves of Auburn Avenue or on the west side or within the gates of the colleges, were reminded every day of their marginal position in the city by police harassment, their neighborhoods’ lack of city services, or their homes’ proximity to a city dump. Racial subordination and segregation consigned all black Atlantans to the same living conditions no matter their wealth or background.12

Working-class African American neighborhood, 1930s. (Charles Forrest Palmer Collection, Special Collections Department, Robert W. Woodruff Library, Emory University)

While the Atlanta riot marked the retrenchment of Jim Crow in Atlanta, it also produced a revitalization of black community life as African Americans fought back and sought to protect themselves from the white onslaught. As soon as black Atlantans understood the fury and size of the white mobs involved in the riot, they began to organize for the defense of their own neighborhoods. In districts throughout the city, black men armed themselves through an underground network, creating informal militias to patrol their communities and fend off white attack. In working-class Dark Town, adjacent to the central business district, such a band of black men shot out the streetlights and at any intruders, successfully thwarting them. In south Atlanta's Brownsville, an ambush surprised a group of county police and white vigilantes intending to confiscate firearms in the neighborhood, resulting in the death of one of the police officers and injuries for many of the interlopers. Black institutions, including churches and the colleges, opened their doors to their neighbors, and this show of racial solidarity protected many African Americans from white attack. Indeed, the worse place for black Atlantans to be caught during the riot was outside their neighborhoods, and without community support.13

Black Atlanta's swift response reflected the ways in which African Americans had always responded to white supremacy and the expanding Jim Crow order. Defending themselves against the myriad ways in which white Atlantans actively and passively marginalized them from the political, social, and economic mainstream of city life, black Atlantans forged their own distinct, parallel city behind the veil of Jim Crow. In the words of historian Earl Lewis, they turned the negative white impulses of “segregation” into the constructive force of “congregation” by shifting their energies inward away from the white city to find support and sustenance within their own communities. In this way, they created an independent and autonomous life outside the knowledge, experience, and understanding of the whites who would control them.14

After the riot, black Atlantans sought again to strengthen their institutions to protect themselves against the white city. While at one time they had lived scattered throughout the city in small enclaves near their employment, after the riot African Americans intensified their concentration in black Atlanta's most established neighborhoods, such as those close to the Auburn Avenue business district or the west side, where Atlanta University (AU), and Spelman, Morehouse, and Morris Brown Colleges were located. While the consolidation of Jim Crow residential segregation was partly responsible for this trend, black Atlantans made the move willingly; anchored by the black economy and the city's most powerful and independent black institutions, these neighborhoods provided the best insulation from the white city and its residents.

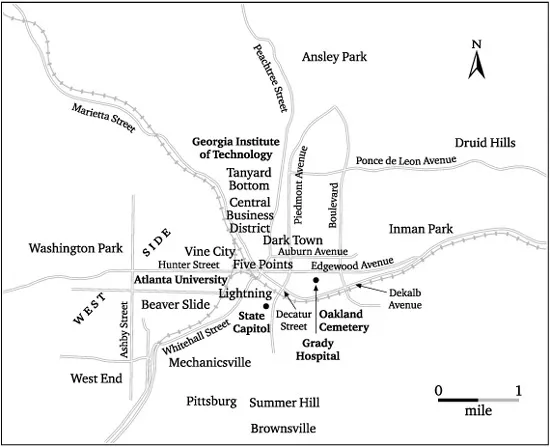

Map 1. Atlanta, 1930. (Adapted from map in Tera Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors after the Civil War [Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997])

Within these enclaves, black Atlantans intensified efforts geared toward community self-help. Both formal and informal social service efforts in black neighborhoods mushroomed after the riot as their residents sought to cope with the hardening segregationist order. The Neighborhood Union, created in the months after the riot, brought women from Atlanta's west side together across class lines to provide many of the social services city Officials denied to black neighborhoods. For example, the agency built a playground on the campus of Morehouse College to provide children with safe recreation. It al...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Black Politics in New Deal Atlanta

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Maps and Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- PART I Life at the Margins

- PART II The New Deal

- PART III The New Deal & Local Politics in Black and White

- PART IV Wartime Atlanta & the Struggle for Inclusion

- Epilogue The Politics of Inclusion

- Appendix Tables

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Black Politics in New Deal Atlanta by Karen Ferguson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.