![]()

1 Designs of the Monied Gentry

The first designs for internal improvement in the new United States were articulated by such revolutionary heroes as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Robert Morris, and Philip Schuyler. Members of a class George Washington called the “monied gentry,” these individuals shared a common commitment to the success of the republican experiment, the security of the Union, the preservation of the national government, and the prosperity of their countrymen. Possessed of continental experience and broad vision, such gentlemen assumed a right to lead based on superior knowledge, patriotic feeling, and what they called “wisdom.” Although the Revolution was eroding all hierarchies of power, these men survived for a time as America’s home-grown aristocrats.

Inland navigation particularly attracted this first generation of American improvers. They saw a rising empire of settlement and commerce in the future American West. Canals and river improvements, designed to connect the interior region with the Atlantic trading communities, promised to facilitate growth and insure the loyal integration of the frontier within the Union. When local politicians and taxpayers balked at improvers’ grand schemes of public investment, they formed corporations instead, which enjoyed government sanction to solicit private subscriptions. By thus farming out the work of the sovereign government, these elite promoters appeared to pursue the public good at private expense, while they reduced the need to win public approval or taxpayer support for their futuristic schemes. In other words, such postwar gentry found that their power to tax the people had been weakened by the Revolution, but their authority to set the agenda for future development had not yet disintegrated completely.

These gentleman-entrepreneurs designed on a fluid field: commercial networks, trade routes, settlement patterns, even the opinions of scientists and technical experts—all floated as on a pool of opportunity, waiting for the organizing hand of improvers to anchor the first elements. Everything was experimental. Neither engineers nor economists yet enjoyed the skill or credibility to settle competing claims made by politicians. Yet men of large vision understood that the first few steps might define the framework of development for generations to come. The future literally depended on seizing advantages now. If these gentlemen’s favorite local projects could chart the course of national growth, so much the better for them and their neighbors.

Because they planned on a large scale, members of the “monied gentry” tended to favor an energetic federal government and integrated national development. They never failed to stress moral and intellectual uplift along with material well-being as the objects of their improvements, and they renounced the vulgar interests of mere adventurers in speculation. Nevertheless, their pet projects reflected local and selfish interests as much as any others. Almost nobody promoting internal improvements conceded the importance of works outside his own region. Instead, all kinds of promoters schemed to have government favor their own improvements while deflating the claims of others. As a result, the rhetoric of disinterestedness that united such gentleman-improvers rings a little false in historians’ ears—and it engendered some suspicions among their contemporaries as well.

Before long, the presumed authority of the monied gentry to make designs based on their patriotic motives, superior knowledge, benevolence, or wisdom gave way to the insistent demands of more common people to make all decisions affecting the future of American liberty through the system of popular politics. Enduring suspicions toward any ruling class predisposed many ordinary voters to question the pretensions of their “betters,” while the failure of elites to prove the superiority or disinterestedness of their schemes exposed early designers as perhaps no less ambitious than other “grasping” persons. Thus belief and experience conspired to unseat traditional authorities in the experimental United States. No individual better illustrates both the impulse to create designs and the decline of authority to implement them than the nation’s first president, George Washington.

George Washington’s Republican Vision

October 1783 found Washington in Princeton, New Jersey, biding his time, having “the enjoyment of peace, without the final declaration of it.” Formalities bound him to the army but left him nothing useful to do. Inactivity depressed him, and for relief he recently had toured the waterways of upstate New York, dreaming of interior development. Poring over available maps and information, the restless general marveled that Providence had “dealt her favors to us with so profuse a hand. Would to God,” he concluded, “we may have wisdom enough to improve them.”1 It is important that Washington used the term “wisdom” in this homely context. His prayer was not for money, or time, or technical expertise; it was for wisdom. Apparently he worried about the wisdom of his newly liberated countrymen, and he questioned their ability or willingness to do the right thing. His Continental Army had suffered scandalously at the hands of the people; just then Congress sat in exile in Princeton, driven out of Philadelphia by angry unpaid soldiers. Great possibilities—or anarchy—lay ahead. Washington’s phrase resonated with the urgency and apprehension that filled the atmosphere of postwar America.

Like revolutionaries everywhere, Washington cherished a vision of the rising new nation he had worked so hard to rescue from the British. His vision comprehended the existing Atlantic community, while his imagination leaped across the mountains to embrace seemingly limitless space in the continental interior. Western lands had fascinated Washington since his 1748 trip as a youthful surveyor into Lord Fairfax’s western claims. In the last years before the Revolution, he had labored to pry open the western country and to interest provincial legislatures in the Potomac route to the West. “Immense advantages” awaited Virginia and Maryland, he argued in 1770, if they would make the Potomac a great “Channel of Commerce between Great Britain” and the interior.2

The word “channel” here originally meant less than modern readers might expect, for Washington’s early vision was extremely limited, and therefore practicable. By clearing boulders and trash from the riverbeds and building portage roads between streams (or around unmovable obstructions), he hoped to facilitate the passage of canoes and flat-bottomed bateaux from the western to the eastern waterways, especially during high-water seasons. The downstream movement of bulky furs and foodstuffs concerned him more than return shipments of manufactured goods, which could better stand the cost of land transportation. Such limited expectations justified the small sums often spent by individuals and local governments toward the improvement of these rivers. At the same time European engineering offered splendid encouragement for greater ambitions. For nearly a century the famous Languedoc Canal had carried passengers and goods across the south of France, through more than one hundred locks and fifty aqueducts. More recently the duke of Bridgewater’s English canal convinced American dreamers that technical solutions lay just ahead even for the Great Falls of the Potomac, an eighty-foot shelf of rock some twenty miles upstream from Washington’s Mount Vernon.3

The Revolutionary War postponed the improvement of the Potomac, but Washington’s interest in the project only increased with the winning of independence. In early 1784 he explained again to Jefferson the compelling advantages of the Potomac navigation, adding now his fear that the “Yorkers” would lose “no time” in improving their own route to the Great Lakes. Most Virginians did not see the “truly wise policy” of Potomac improvement, and they certainly resisted “drawing money from them for such a purpose.” Even so, Washington hoped, as he went west in September to explore the Ohio country, that men of “discernment and liberality” could be made to see the value of the project.4

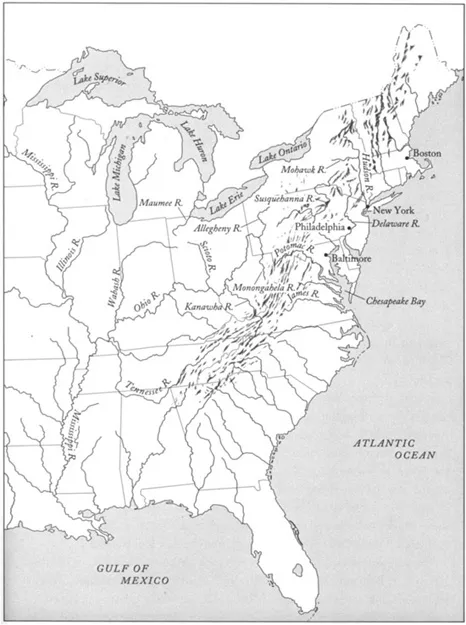

Firsthand knowledge only quickened Washington’s convictions. He saw or heard how a short portage between the Miami and Sandusky Rivers might link the whole Great Lakes system with the Ohio; how the Allegheny, the Monongahela, the Kanawha, and their many branches might be connected with the Susquehannah, Potomac, and James to form passages from the Ohio waters to the Atlantic coast. Geographical features came so near to meeting in a network that it seemed to Washington as if nature had designed the interior region expressly for improvement by the new United States (Map 1). As things stood in 1784, however, such improvements were not forthcoming. Western Pennsylvanians talked of opening the Susquehannah (which ran to Baltimore), but Philadelphia’s merchants blocked their efforts. New York’s water-level route to the lakes was well known, but British troops still occupied Niagara and other Great Lakes forts. The people of the West themselves had not the means to make improvements and—more distressing to Washington—had no “excitements to industry” because the “luxuriency of the Soil” gave too easy a living, while the impossibility of trade discouraged ambition. Open a good communication with these settlements, however, and exports to the East must be increased “astonishingly.” Even more important, he presumed that the political allegiance of the pioneers would follow their commerce: so long as Spain blocked the Mississippi and Britain the Great Lakes, the Atlantic states enjoyed a unique opportunity to “apply the cement of interest,” binding all parts of the Union with “one indissolvable band.”5

“Great Falls of the Potomac,” upstream a few miles from the new federal capital city. The falls symbolized both literally and figuratively the enormous challenge facing American internal improvers. Lithograph by T. Cartwright after a painting by George Beck, 1802. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Map 1. Geographical features of the eastern United States, showing the potential routes that captured George Washington’s geopolitical imagination.

The Potomac navigation activated Washington’s whole vision of the rising American empire. The West held the key to America’s future greatness. The “vacant” lands back of the Atlantic states promised safety and prosperity for generations to come. Agriculture, he assumed, would occupy the masses; but without markets frontier farmers regressed toward a state of nature. Therefore commerce must propel the nation forward, and inland navigation would bind the wilderness communities to the Union by chains of commercial interest. National character, prosperity, respect among nations, the security of the Union (and by implication the liberty that flowed from independence)—public issues at the center of Washington’s concern—all depended on embracing westward emigration within the American national system. Inland navigation made the United States conceivable, and Washington’s vision soared high above the diggings: “I wish to see the sons and daughters of the world in Peace and busily employed in the more agreeable amusement of fulfilling the first and great commandment, Increase and Multiply: as an encouragement to which we have opened the fertile plains of the Ohio to the poor, the needy and the oppressed of the Earth.” Washington’s America was nothing less than “the Land of promise, with milk and honey.”6

Private interest, Virginia pride, and concern for the welfare of the Union mingled in Washington’s mind as he gazed west from the banks of his river. The value of nearly 60,000 acres of his own western lands promised to rise with the opening of tramontane commerce.7 His sense of urgency and his insistence that the Potomac was by nature the ideal route reflected a keen spirit of rivalry with other states that antedated the Revolution. Yet his persistent use of the language of national interest and political security rang true despite his obvious personal interests. For years he had cultivated national credibility; now he would use it to promote his design for the river, Virginia, and the new United States.

Washington pressed his vision on everyone he knew. Henry Knox, Richard Henry Lee, Benjamin Harrison, Lafayette, Chastellux, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, Charles Carroll, Robert Morris—all received long letters full of enthusiasm about inland navigation and the western country. In these same letters Washington often brooded over signs of chaos and disorder that seemed to be multiplying across America, reflecting the close connection in his mind between the question of government power and the opportunity to found an American empire. Petty visions competed everywhere. Interested parties worked against his navigation schemes in order to advance their own or to protect transient advantages. In the West, squatters seized Washington’s unimproved lands and dared any man to dispossess them. Speculators engrossed huge tracts, while northwest of the Ohio settlers provoked Indian reprisals. It seemed as if nothing could be done about these outrages, the general confided to his friend Henry Knox, because the people in the states were “torn by internal disputes, or supinely negligent and inattentive to every thing which is not local and selfinteresting.”8

In a seamless tapestry Washington saw his trouble with frontier squatters, the selfish localism of his Virginia neighbors, the indifference of the states toward the federal Congress, irresponsibility in public finance, and reckless assaults on the public domain all springing from the same malaise. “The want of energy in the Federal government,” he concluded, “has brought our politics and credit to the brink of a precipice; a step or two farther must plunge us into a Sea of Troubles, perhaps anarchy and confusion.” Similar conflicts plagued the Potomac navigation. Such engineers as could be found assured Washington and his friends that all technical problems could be solved. The objective was compelling, and the estimates by “experts” were encouraging; only human folly seemed to stand in the way. His prescription for national health? Instill vigor in the federal government, adopt an orderly plan for settling the West, and set to work immediately on inland navigation.9

Because the Potomac formed the boundary between Maryland and Virginia, both states had to sanction improvements. But Baltimore merchants schemed to block the project in favor of a Susquehannah Canal chartered in Maryland in 1783, while Virginians outside the Potomac Valley showed a maddening indifference to the general’s grand design. Finally in late 1784, the two legislatures authorized a joint-stock company to improve the river and collect tolls in perpetuity, according to fixed schedules. Commissioners were named to lay out and construct good roads (at public expense) from the head of navigation to the “most convenient” western waters, thereby completing communications with the frontier.10

The charter delighted Washington, yet his thoughts kept drifting back to the political urgency behind the project. He seemed disappointed that the two states “under their present pressure of debts” were so “incompetent” to carry on the work: would private parties really take hold? To Robert Morris, Washington explained that were he “disposed to encounter present inconvenience for a future income” he would “hazard all the money” he could raise on the Potomac navigation. But in fact he did not hazard all his money, and there lingered in his views a nagging concern that where his own purse failed others would too. Friends of the measure were “sanguine,” he wrote to Lafayette, but “good wishes” were “more at command, than money.” Because “extensive political consequences” depended on these projects, he felt “pained by every doubt of obtaining the means” for their completion.11

In Washington’s mind there was much more to inland navigation than clearing boulders from a riverbed and digging canals. He was building a nation as well as a waterway, and he preferred to think that men of vision would see the wisdom of his plan, seize it with the sovereign hands of government, and pursue it to the benefit of all. But Washington knew how investors behaved. Some subscribers were “actuated” by “public spirit,” and others by the hope of “salutary effects.” The latter “must naturally incline” toward support, but those who were “unconnected with the river” would not. Why not vest such an enterprise by law with “a kind of pr...