![]()

chapter one children seen and heard

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

First Communion Celebrations

All during the Mass, we prepare our hearts to welcome Jesus, who comes to us in Holy Communion. When Communion time comes, the priest or Eucharistic minister holds the Host up to each of us and says, ‘‘The body of Christ.’’ . . . After we receive Jesus in Holy Communion, we return to our places to pray and sing. The word Communion means that we are united with Jesus Christ and one another.—Coming to Jesus (1999)

Blessed Sacrament’s textbook, Coming to Jesus, from Sadlier’s Coming to Faith Series, tells children what to expect during their First Communion. In just a few sentences, the children learn what they should do during Mass—prepare their hearts, pray, sing —and the result of receiving the Sacrament—it connects the children with Jesus and fellow Catholics. As the children would soon learn, however, First Communion encompasses much more than this generalization reveals. It is a rich, complicated, and dynamic ritual that has the potential to do more than unite the children with Jesus and the Church. In the children’s First Communion Mass, they would dance, present the offering, and speak before the congregation. And in so doing they would enact and help shape their parish’s ethnic heritage as well as its Catholic traditions. The usual descriptions erase these aspects of heritage and action. They focus instead on the uniform structure of the ritual and its intended universal result. This focus both flattens the ritual and assumes that it will succeed in bringing the child and the Church together. Though this union may occur on a theological level, it is not necessarily true that every child leaves the altar table feeling connected to the Church. I would have to wait until I talked with the children after their participation in the Eucharist to see if the ritual succeeded in the ways that they were told it would.

Although I could not learn how the Sacrament affected individual children from the liturgies, the ceremonies did offer great insight into the parish’s self-understanding. For, in this moment of celebration, both Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church and Holy Cross Catholic Church brought together the characteristics that catechists felt best represented the parish’s unique identity. Within these liturgies the parishes signaled their ethnic as well as regional identities. In the South (unlike in most other parts of the country), to be Catholic, let alone an African American or a Hispanic Catholic, is to be suspect. Each of the First Communion Masses, however, demonstrated that regional and ethnic identity were of a piece with their Catholic practices.

I begin this chapter with a description of Holy Cross’s First Communion day, a description that raises many themes that I will discussmore fully in the following chapters, such as the children’s understanding of gestures, dress, and transubstantiation, the process by which the bread and wine become Jesus’ body and blood during the Mass. I follow this description with an analysis of what this liturgy revealed about the parishes’ identities and what they hoped to pass on to the communicants.1 I then follow the same format to examine Blessed Sacrament’s bilingual First Communion Mass as well as its supplemental Spanish Mass. From there, Imove to a discussion of how these liturgies reinforced the participants’ Catholic and parish-specific identities that the adults sought to pass on to the children, paying particular attention to how the history of Catholicism in the South and patterns of migration have shaped these identities.

Holy Cross’s First Communion

As I opened the door to the Activity Center just before 9:30 a.m. on a rainy First Communion Saturday, I could see Ryan, who was standing just inside the door, greeting his friend Michael with a big hug, exclaiming, ‘‘Today is the big day.’’When I walked in the building, near to where Cara’smother was fixing Cara’smakeup, I quickly became aware that First Communion preparations were well under way. The boys had gathered in one classroom where some of them were dancing, others were drawing on the blackboard, and still others were checking to make sure everyone’s tie was hanging correctly.Meanwhile, the girls wandered up and down the hallway showing off their dresses, adjusting their veils, and offering each other good luck.

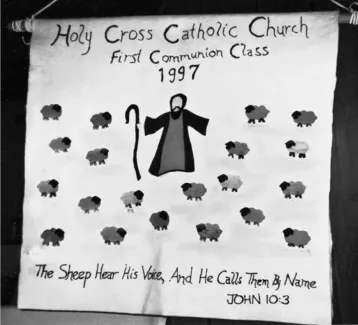

Soon, however, the rain had stopped, so Mr. Thomas, a catechist and the parent of a communicant, took the class outside and lined the communicants up for their procession into the church. As the class made its final preparations, I hurried over to the church. Family and friends already crowded the sanctuary. I found my place next to Ms. Williams, the assistant catechist, on a folding chair in front of the first pew on the right side of the room. From here I watched two African American communicants, Cara and John, who had entered the church through a side door, talking with each other as they waited to begin the welcome dance. The drumbeat started, and the chorus began singing in a mix of Swahili and English, ‘‘Funga la fia. Ashé, ashé,’’ to which the children answered, ‘‘Funga la fia. We welcome you, Funga la fia. Ashé ashé,’’ in a traditional African call-and-response pattern. Then John, Cara, and Ezekiel, who was too far back in the wings for me to see him before Mass, moved out from the wings on the right, sashaying toward the center of the church as they brought their arms out to their sides and in close to their bodies, matching the movement of their feet. At the center aisle, they met the three children who had begun the dance from the left-hand side of the altar, and together they danced up and down the aisle. The congregation began to clap in time to the drum, a beat that Ms. Michael, an African American dancer and lifetime member of Holy Cross, played at the front of the sanctuary. This dance simultaneously announced the start of the First Communion celebration and the parish’s African American heritage. Once these dancers reached their pews, the rest of their class, which had been waiting in the vestibule at the back of the church, proceeded two by two down the aisle to the drumbeat. They marched behind the 1997 First Communion banner, which was emblazoned with Jesus standing in the middle of his sheep—pink, orange, and blue—with one sheep for each child (Figure 1).2 The banner reflected the theme for this year’s Communion class: ‘‘The sheep hear his voice, and he calls them by name’’ (Jn 10:3).3 The children found their families’ pews and sat at the end closest to the center aisle. As Father David E. Barry, S.J., began the Mass, I turned to look at the children sitting in the first few pews behind me. Many of them had begun sucking or biting on their fingers by the end of the first reading. Halfway through the second reading, the communicants began shifting in their seats. As the murmur from the children quieted, Father Barry, who now stood at the lectern, began reading from the Gospel according to John, which he followed with a homily that recounted his visit to a sheep ranch. He said, ‘‘It was during that time that I finally understood what John was writing about in this Gospel. There were more sheep than there are people in New York City. . . . When it came the time for the shearing, that’s when I noticed that when each shepherd called out the word, those sheep who were all mixed together recognized his voice. . . . And all those particular sheep separated themselves from the other sheep and found their shepherd, . . . which brings us to the point.We hear Jesus say to us, ‘Listen to my voice. . . . If you belong tome you will only listen to my voice. You will only follow me.’ And this is what the good shepherd says, ‘I love you. I need you. I want you.’ And he says that to you constantly day in and day out.’’4 The congregation then said, ‘‘Amen.’’ However, I did not hear any of the communicants’ voices, perhaps because they did not know when to speak, or perhaps because their minds were focused on the impending Sacrament.

FIGURE 1. Holy Cross’s 1997 First Communion banner

After the prayers of petition, which the children had written themselves to thank their teachers, godparents, and God, the congregation sat while Ms. Smith, the African American woman who heads the gospel choir, played the opening bars of the gospel hymn ‘‘I’m in Love with Jesus Christ’’ on the electric piano.5 One by one, parishioners began to clap until almost the entire congregation marked the beat together.When the music began, the stilted quality of the Mass disappeared, replaced by the usual comfort, rhythm, and fullness of Holy Cross’s 9:00 a.m. Mass. ‘‘My First Communion was nothing like this,’’ remarked one communicant’s godmother, a white woman who flew in from Maryland for the event and sat in the pew directly behind me. Perhaps she was commenting on the more stereotypically Protestant style of the gospel music, the children’s African dance, or the congregation’s clapping. The soloist’s voice grew in intensity, signaling the hymn’s end. At this cue, Father Barry went to the front of the church. Simultaneously, four communicants and the altar servers headed down the aisle, bringing the gifts to the priest. The ruffling of dresses as the girls shifted in their seats and the general sense of movement in the church indicated the increasing excitement, as Father washed his hands with the holy water. From the children’s surreptitious attempts to practice performing the sign of the cross and making ‘‘thrones for Jesus,’’ it appeared that while they were trying to seem as if they were paying attention, they were anxiously anticipating receiving the bread and wine. (The sense of anticipation, I would learn, had a great in- fluence on their interpretation of the Sacrament.) First, however, Father Barry had to consecrate the Eucharist, or as the children had learned in their classes, he had to bless the bread and wine, transforming them into the body and blood of Christ.

The recitation of the Our Father was the only part of the liturgy of the Eucharist that broke through these last-minute preparations and successfully encouraged the communicants to participate in the Mass. Now everyone in the pews held each other’s hands saying the Lord’s Prayer, ‘‘Our Father, who art in heaven,’’ in an unbroken chain throughout the church.6 When each person let go of his or her neighbors’ hands, the congregation shared the Kiss of Peace. At this point most people left the pews to give hugs and kisses to their friends and neighbors (as they did each Sunday) and to wish the children congratulations. They offered signs of peace to those whom they could not reach, especially those in the balcony with the choir. Soon the piano music let the congregation know that it was time to return to their seats.

The boys in their white shirts and red ties and the girls in their white Communion dresses watched intently as Father Barry lifted the Host before the congregation. Again, the rustle of lace attracted my attention, and I turned to see Maureen, one of two white communicants, with short brown hair pulled back by a white headband, scooting to the edge of her pew as she sucked on her thumb. Since she sat in the first pew, Maureen would be the first one to receive the Sacrament. She looked over to her mother and her godparents for reassurance as the priest offered Communion to the two altar girls who stood on either side of him. The choir began to hum a gospel hymn, and a ripple of energy moved through the church. The 1997 First Communion class at Holy Cross was about to receive the Eucharist. Maureen’s godfather signaled that the time had finally arrived. After Maureen had watched the congregation receive Communion countless times in the last seven years, her turn had come at last. She slowly rose to her feet, holding her palms together in front of the white sash that defined her waist. With her godfather’s hand on her shoulder, Maureen walked anxiously toward the priest, whose white vestments of celebration had re- placed the green worn on ordinary Sundays. ‘‘The body of Christ,’’ he said, as he placed the consecrated Host in her hand. She put the Host into her mouth and then slowly walked to Ms. Hudson, the director of religious education, who held the chalice full of wine. Maureen sipped the wine. She performed the sign of the cross and returned to her pew, where she knelt and said her prayer of thanksgiving as Father Barry held aloft the consecrated bread that Maureen’s classmate Matt, a Filipino with short black hair, had also waited so long to taste. With each step down the aisle, Matt’s excitement (and self-consciousness) seemed to increase, for he knew that everyone was watching only him. With wide eyes and an anxious smile, he walked stiffly to the priest.His shoulders relaxed and his smile broadened as Father Barry placed the Host in his hands. As Matt put the Host in his mouth, the clicks of picture taking were emphasized by the burst of a flash, just as they were for each communicant.

I looked at Matt’s face as I would look at those of his nineteen classmates as they received their first taste of the Sacrament.When the communicants reached the altar their usual smiles left their faces, replaced by serious expressions that remained as they placed the Host in their mouths. Those communicants who remembered crossed themselves as they shifted over to Ms. Hudson, who offered them the wine (Figure 2). Others bowed, and still a third group forgot to make any motion and just stepped quietly to the right. Standing in front of Ms. Hudson, they carefully took the cup. They became a bit shakier as the tart wine touched their lips. Many of them scrunched up their faces as if they had just bitten into a lemon. Some of the children recovered from the taste and burst into big grins as they returned to their seats. Others returned to their pews with puckered faces, eliciting laughter from the congregation.

Once the communicants and the other eligible Catholics in the congregation had received the Eucharist, Father Barry returned to the front of the church. He stood by the paschal, or Easter, candle and said: ‘‘The second sacrament of initiation is First Communion. So we return to that great symbol of lighting the candle for the light of the world, using the Easter candle, which is the light of Christ and the light of the world.’’ Father Barry then moved behind the lectern and the Easter candle as the children walked one by one with their godparents to light their candles. The soloist began an impassioned rendition of ‘‘Jesus, You’re the Center of My Joy,’’ as Maureen’s godmother lit Maureen’s First Communion candle from the Easter candle and then handed it to her goddaughter.Her classmates followed, having their candles lit by their godparents and taking their places on the dais. With candles in hand, the children then lined up for a final picture with their godparents and Father Barry behind them. After the congregation took what the communicants believed were ‘‘too many pictures,’’ the children blew out their candles, and to the hymn ‘‘I Just Want to Thank You, Lord,’’ they moved back down the aisle in haphazardly assembled pairs that quickly formed a mass in the middle of the aisle, unlike the two straight lines by which they had entered the sanctuary.

FIGURE 2. A First Communicant receives the Eucharist

After the children proceeded out of the church, everyone headed to the Activity Center. Walking into the downstairs meeting room, I heard Julie, a shy blonde white girl, describing her dress to Father Barry. ‘‘It’s a bridesmaid’s dress really,’’ she explained. Father Barry replied, ‘‘You’re like the bride of Christ now.’’ Julie had no reaction to this comment, if she even heard it, which did not surprise me, since none of the teachers or parents ever mentioned that the communicants might become brides of Christ.However, this comment turned my attention to the power of dress. Although Julie did not explicitly make the connection between her dress and being a bride, Father Barry’s comment emphasized that there was a relationship that many adults recognized between this dress and the bridal gown Julie might wear someday. While I pondered the dress’s symbolism, Julie spun around in circles watching the dress’s skirt puff out around her (an activity I remembered well from my own girlhood).

Listening to the conversations as I walked through the room, I headed to the kitchen to help the older women of the parish fix the plates for lunch. Each plate displayed the feast of a true southern celebration, marked most clearly by the presence of congealed salad. Each plate held a square of red Jell-O salad centered on a lettuce leaf, candied yams, wild rice, turkey, and gravy. Each person also received a piece of sheet cake, which had been decorated with a Bible and a scroll.

Once everyone had been served, I carried my plate out of the kitchen and found a seat with Ms.Wright-Jukes, the lead catechist, her parents, and her son, a First Communicant. Before long, Father Barry joined us too. He quickly confessed that he had never seen a sheep or a sheep farm, despite the claims he made in his homily. I was shocked and a little saddened by the confession. No one else seemed bothered, although they were all somewhat surprised. We lingered together a long time. By the time we got over our surprise and finished laughing, we were the only people left in the room. Everyone else had probably gone to their own family celebrations. I walked out to the parking lot thinking about how the communicants would la...