![]()

PART I

Constructing Material religion Material Religion

![]()

Chapter 1

THE CITY CHURCHES

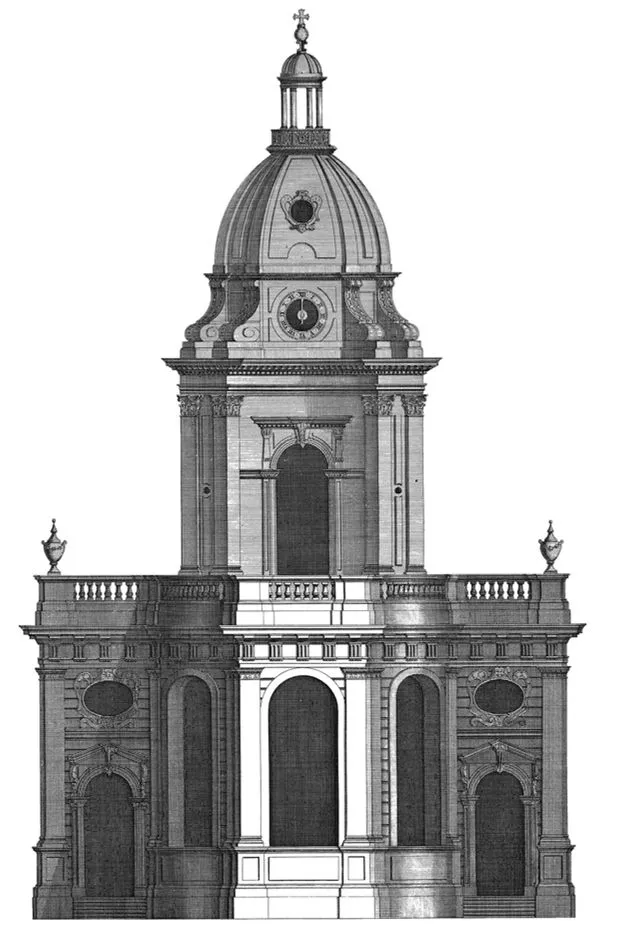

In June 1753 the Gentleman’s Magazine published an engraving of the west prospect of “St. Philip’s Church in Charles Town, South Carolina” (FIG. 1.1).1 Shade and shadow exaggerate the monumentality of the building’s three giant-order Tuscan porticos, while engaged pilasters carrying a continuous cornice extend the classical order to the body of the church. Rising from behind the porticos, a tall cupola of two octagonal stages supports a dome, a square lantern, and a cock weathervane.2 St. Philip’s was far superior in finish and scale to the tenements, small shops, and houses that lined the streets of the colonial city (FI G. 1.2). A description accompanying the image praised the building as “one of the most regular and complete structures of the kind in America. The design was sent to us from Charles Town, where it has a very advantageous situation, at the upper end of a broad and extensive street.”3 The engraving, completed sometime before 1737, was probably sent to London by Charles Woodmason, a prominent South Carolina Anglican minister who in the subsequent edition of the Gentleman’s Magazine published a poem extolling Carolina as a “Second Carthage” where “Domes, temples, bridges, rise in distant views / And sumptuous palaces the sight amuse.”4 When recounting domes and temples, the poet-priest certainly had in mind the soaring cupola and triple porticos of St. Philip’s. Woodmason was not alone in his praise for the building. Writing just prior to the completion of the new church in 1722, South Carolina’s Anglican clergy celebrated the church as “not paralleled in his Majesty’s Dominions in America.”5 Published in a London monthly, the west prospect of St. Philip’s asserted an architectural sophistication at the fringe of empire that must have surprised the magazine’s cosmopolitan readership.

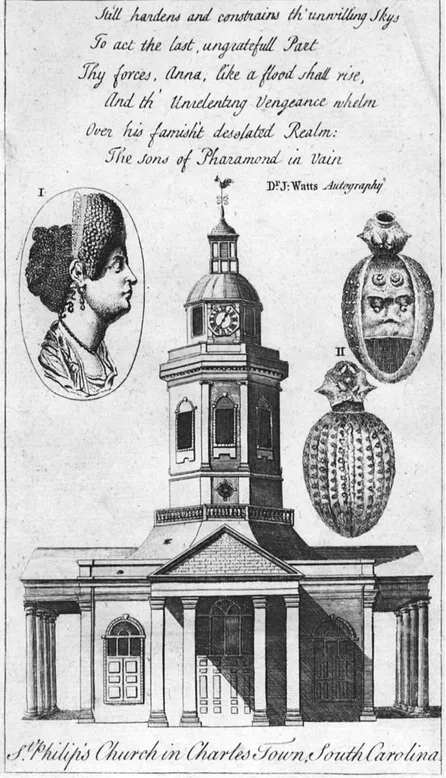

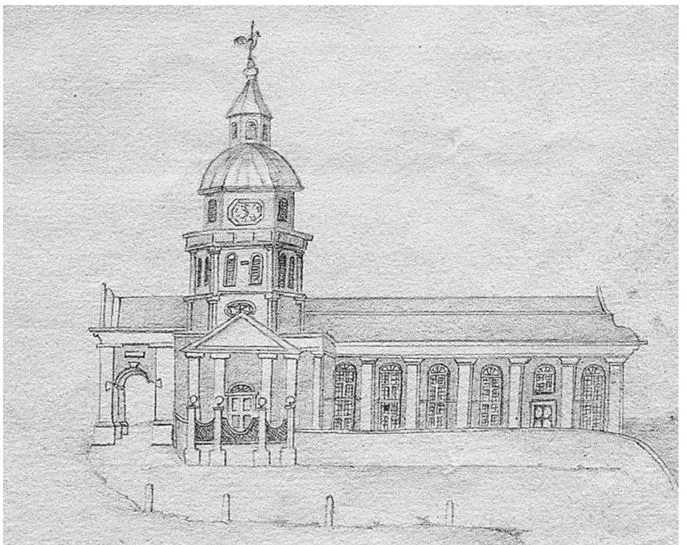

Standing on the highest point within the city walls, St. Philip’s cupola reigned over Charleston, and its southern portico dominated the city’s principal north-south street (FIG. 1.3). As evident in the 1739 Ichnography of Charles-Town, the church of St. Philip’s was easily the principal building in this colonial town, the capital of a colony with an estimated 20,000 white and almost 40,000 enslaved black inhabitants by 1740.6 The church stood at the northern end of the city in blocks that were in the early eighteenth century still fairly open; just to the northwest stood the colony’s powder magazine. The blocks immediately to the south were densely constructed with merchants’ houses, shops, tenements, and warehouses nearest the wharfs. While some of the wealthiest might leave a multistoried private house like the few evident in the 1739 Bishop Roberts’s view of Charleston, most Anglicans who came to the church for regular worship departed domestic settings of only a few very plain chambers, often shared with a number of other people. Three- and four-story brick tenements with multiple, irregularly located doors and often unstable wood balconies projecting overhead lined the street and stood cheek by jowl with warehouses and unassuming frame shops less than ten feet wide. Rising from the midst of this landscape, St. Philip’s seemed wholly other. More than sixty feet wide and seventy feet long, the church occupied a more prominent place than any other space in the real or imaginary landscape of the majority of Carolina Anglicans.

FIGURE 1.1 Engraving titled “St. Philip’s Church in Charles Town, South Carolina” (Gentleman’s Magazine, June 1753)

FIGURE 1.2 Thomas You, St. Philip’s Church, Charleston, ca. 1760 (South Carolina Historical Society)

Begun in 1711, St. Philip’s was the first of three Anglican churches erected in colonial South Carolina that demonstrated the remarkable cosmopolitan fluency of this remote outpost of the British Empire. Together with St. Michael’s, also in Charleston (1751-62), and Prince William’s Parish Church (1751-53), in a remote plantation parish, St. Philip’s was one colonial example of a revolution in elite Anglican church design. In 1711 Parliament passed an act for building fifty new churches in London and her immediate environs, initiating a flurry of discussion and debate among English architects and clergy about appropriate design for Anglican churches. While only fourteen new churches were built in London as a direct result of this act, the process of formulating the urban Anglican church informed an extraordinary number of new churches rising in cities throughout the British Empire.7 In London and elsewhere, these new churches often boasted substantial masonry construction, steeples, and porticos as markers of their participation in an emerging cosmopolitan identity.8 But in Charleston, as in her counterparts on the English mainland, Anglican church designers turned to London churches not as ideal models to be replicated but as fashionable design sources for consideration in local construction. The architectural histories of these three South Carolina churches suggest a complex design process shaped by numerous individuals drawing from a multiplicity of sources. From the new city churches in London to theological discourses on precedents for form and ritual and the design challenges of integrating the church into the public sphere, Anglicans in colonial South Carolina integrated multiple sources and responded to diverse challenges as they raised these three markers of South Carolina’s emerging cosmopolitan identity.

FIGURE 1.3 Detail of W. H. Toms, The Ichnography of Charles-Town at High Water, 1739. St. Philip’s is designated “A” on the plan (lower right).

ON MARCH 1, 1711, South Carolina’s General Assembly passed an act charging six church commissioners with the responsibility of erecting a new brick church in their city to replace their first building, a smaller wooden church standing near the city gates, then about a quarter century old.9 The commissioners were empowered to receive subscriptions and “to purchase and to take a grant of a town lot or lots . . . and to build the Church of such height, dimensions, materials, and form as [the commissioners] shall think fit.”10 The act also established taxes on rum, slaves, and other merchandise to support construction. Of those six commissioners, one was the Reverend Dr. Gideon Johnston, the Anglican commissary in the colony and minister to the city parish, and five were prominent lay Anglicans: William Rhett, Alexander Parris, William Gibbons, John Bee, and Jacob Satur. The commissioners selected a new site at the northern end of the city—the highest point within the city walls—for the erection of their monumental brick church.

The church as it was begun in 1711, however, differed greatly from the building that opened for services in 1723 and was finally completed in 1733. In the spring of 1713, with the building shell under way, Gideon Johnston sailed for London carrying a list of complaints about various acts of the Carolina Assembly that had injured “the Privileges of the Clergy.”11 The letter was addressed to both the bishop of London and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. As part of their report on the state of the church in the colony, the clergy mentioned that Anglicans “are now building a large brick Church at Charles Town 100 foot long in the clear and 45 broad.”12 The church as it was completed in 1733, however, measured seventy-four feet by sixty-two feet, with a western vestibule measuring thirty-seven by sixty-two. In the midst of construction, the church had been fundamentally redesigned.

Fairly soon after he arrived in London, Johnston received the news that a hurricane had extensively damaged the unroofed shell of the new church in Charleston, causing £100,000 damage to the building.13 According to another report, the church was “blown down and demolished by a furious Hurricane.”14 This first hurricane in September 1713 was followed by another in November of the following year. After hearing the news of the second storm, Johnston noted in a letter to the S P G that the new brick church had been ready to roof, but that it “is now considerably damaged by this storm, ye windows broken and shattered to pieces.” Another commentator noted that after the 1714 hurricane, only the water table remained of the building’s long northern and southern walls.15 Undaunted, Johnston desired to make “a second effect, and design, please God to prevent a like accident, to carry it to its former height, I hope people will be so charitable to assist me in so good a design.”16 After learning of the destruction of the incomplete St. Philip’s, Johnston turned his efforts to “procuring subscriptions for ye building a church in his parish among ye merchants trading to that place.” Without support from London merchants, Johnston noted, “it is not possible to finish [the church].”17 When Johnston returned to Charleston in the fall of 1715, he commented that “nothing has been done to our new Church since its being blown down by the Hurricane.”18 The church remained a ruined shell for another five years; the outbreak of the Yemassee Indian War diverted funds and workmen from the church reconstruction to fortification projects.

In December 1720 the Assembly finally turned their attention to the reconstruction of St. Philip’s by passing an act to effect the completion of the church.19 In addition to instituting another rum tax to help fund construction, the act appointed a second set of five commissioners, this time all lay Anglicans: Thomas Hepworth, Ralph Izard, William Blakeway, Alexander Parris, and William Gibbon.20 Parris, the royal treasurer from 1712 to 1735, was the only commissioner named in both 1711 and 1720 and appears to have been a central figure in the construction of the church.21 In Parris’s 1736 obituary, the South Carolina Gazette indicated that he “had very much at heart the building and finishing the present Church in Charles-Town, and was not wanting either by persuasion or example to do all that in him lay to compleat the same.”22

The work of the second set of church commissioners was also greatly encouraged by the arrival of Francis Nicholson as royal governor of South Carolina in May 1721. The Anglican clergy of the colony wrote to the S P G in 1722: “It is chiefly owing to his great example that generous encouragement he hath been pleased to give to do good a work, that the new Church of St. Philip’s Charles City . . . is now in such forwardness that in a few months we hope to see it fitted for Divine Service, a work of that magnitude, regularity, Beauty and stability as will be the greatest monument of this City, an Honor to the Whole Province.”23 From his involvement in the city plans for both Williamsburg, Virginia, and Annapolis, Maryland, and major building programs in South Carolina and other colonies, Nicholson’s reputation in architecture has been well established.24 While governor ...