- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Rural women comprised the largest part of the adult population of Texas until 1940 and in the American South until 1960. On the cotton farms of Central Texas, women's labor was essential. In addition to working untold hours in the fields, women shouldered most family responsibilities: keeping house, sewing clothing, cultivating and cooking food, and bearing and raising children. But despite their contributions to the southern agricultural economy, rural women's stories have remained largely untold.

Using oral history interviews and written memoirs, Rebecca Sharpless weaves a moving account of women's lives on Texas cotton farms. She examines how women from varying ethnic backgrounds — German, Czech, African American, Mexican, and Anglo-American — coped with difficult circumstances. The food they cooked, the houses they kept, the ways in which they balanced field work with housework, all yield insights into the twentieth-century South. And though rural women's lives were filled with routines, many of which were undone almost as soon as they were done, each of their actions was laden with importance, says Sharpless, for the welfare of a woman's entire family depended heavily upon her efforts.

Using oral history interviews and written memoirs, Rebecca Sharpless weaves a moving account of women's lives on Texas cotton farms. She examines how women from varying ethnic backgrounds — German, Czech, African American, Mexican, and Anglo-American — coped with difficult circumstances. The food they cooked, the houses they kept, the ways in which they balanced field work with housework, all yield insights into the twentieth-century South. And though rural women's lives were filled with routines, many of which were undone almost as soon as they were done, each of their actions was laden with importance, says Sharpless, for the welfare of a woman's entire family depended heavily upon her efforts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fertile Ground, Narrow Choices by Rebecca Sharpless in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One: Women, Daughters, Wives, Mothers

Gender and Family Relationships

“To be a [southern] woman has meant, for most, to be a woman among their people,” says Elizabeth Fox-Genovese.1 Like their counterparts elsewhere in the South, many farm women in Central Texas before World War II lived their entire lives among a network of kin, heavily influenced by the other women in their families. Most began life as daughters of farm people, taught by female relatives to carry out their duties. They married, often while they were still in their teens, and began having babies within a year of their marriage. By the time that a farm woman reached her thirtieth birthday, she might have five or six children, and she might continue pregnancy and childbirth for another fifteen years. As old age and widowhood approached, a woman might begin to speculate about who would watch over her in her last years, hopeful that her children and grandchildren would care for her as she had cared for them. Within the sweeping cycles of birth, life, and death, a woman knew that her life was shaped by her sex and defined by her connections as a daughter, wife, and mother. Her experience contrasted greatly with those of her husband and sons even as their choices had great impact on her life. This chapter examines the experiences of women enmeshed within their families.

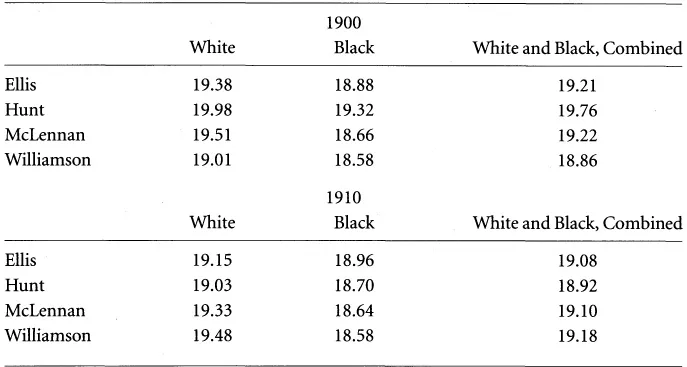

When a woman in the Blackland Prairie married, she was following the cultural expectations of rural southern society. Census data for the region show that the women’s average age at first marriage was nineteen. In rare cases, a girl might marry as young as ten or eleven, or a woman might delay marriage until her midthirties. Black women tended to marry slightly younger than white women, by about six months. The mean for both groups, however, was in the late teens. Table 2 illustrates the average age of marriage for farm women in four Blackland Prairie counties.

TABLE 2. Average Age of Farmers’ Wives at First Marriage in Four Blacklands Counties, by Ethnic Group, 1900 and 1910

Sources: Twelfth Census of the U.S., 1900; Thirteenth Census of the U.S., 1910.

Note: N=100 white women and 50 black women for each county.

Girls of all ethnic groups were brought up with the expectation that they would marry. Mary Hanak Simcik recalled “baptism clothes, and go-to-communion, and brides and grooms and all that stuff” as a Czech Roman Catholic child making doll clothes.2 In the African American community near Robinson, McLennan County, Alice Owens Caufield remembered the hope chest of her aunt Emma Owens Mayfield, whom Alice and her sister Peaches “idolized”: “I can remember Aunt Emma’s hope chest with all them beautiful gowns. Like it was embroidered with the ribbon running. And she always had the neatest things. Aunt Emma was neat and everything had to be just right.”3 Despite her parents’ and brother’s status as sharecroppers, Emma Owens gathered pretty clothes in preparation for her marriage, and her young nieces watched with intense interest.

Popular amusements reflected the expectation of marriage. Among Anglos in the early twentieth century, one of the most widespread activities for young people was an event known as a play-party, in which participants played so-called ring games, singing and clapping a rhythm while moving about the room.4 Many different versions of the ring game existed, and most of them involved the pairing off of young couples.

In his autobiography, folklorist William Owens carefully described the ring games in which he participated while teaching school near Honey Grove, Texas, in the early 1920s. Owens recorded the words to the song and motions to the dance of a ring game called “Going to Boston,” in which a very young couple publicly declared their sentiments about each other:

Come on, boys, let’s go to Boston,

Come on, boys, let’s go to Boston,

Come on, boys, let’s go to Boston,

To see this couple marry.

We formed two lines, the boys facing the girls. The head couple, the girl from the eighth grade, the boy from the ninth, promenaded down the back between the lines while we sang:

Ha-ha, Arthur, I’ll tell your papa,

Ha-ha, Arthur, I’ll tell your papa,

Ha-ha, Arthur, I’ll tell your papa,

That you’re going to marry.

It was Arthur Halliburton, with a flush in his face, a laugh on his lips, a tenderness in his hand for the girl at his side. He left her at the head of the line and led the boys around the girls. Then it was Jennie Linn’s turn to promenade with him, as we sang:

Ha-ha, Jennie Linn, I’ll tell your mama…

She let us know by the pride in her step, the flash in her eye, that she cared only for Arthur. She led the line of girls around the boys and, when she came back to Arthur, they grasped hands and he guided her to the foot of the line, where they stood hand in hand while we sang:

Now they’re married and living in Boston,

Now they’re married and living in Boston,

Now they’re married and living in Boston,

Living on chicken pie.

They had paired off. They were glad for the others to see they had paired off.5

Despite their young ages, Arthur and Jennie Linn were beginning a courtship under the careful scrutiny of their peers. The projected “marriage” involved moving away from the farm. “Boston” could be Boston, Texas, a small community not far from Texarkana, or the large northeastern city, where, undoubtedly, none of the singers had ever been. Although the song indicates some parental disapproval (“I’ll tell your papa”), the “marriage” apparently becomes a satisfactory, if not luxurious, situation. The young couple lives on chicken pie, a typical Sunday southern meal.

Marriage was the expected outcome for both of these near-children. Folklorist Owens moved to Dallas at the end of the school year, so we do not learn of the result of the courtship. But many young people married while still in their teens. Another popular Texas ring game, “Weevilly Wheat,” featured the lyrics to the well-known American folk song “My Pretty Little Miss.” “My Pretty Little Miss” declares that she will go crazy if she doesn’t find a young man by her sixteenth birthday, upcoming the next Sunday.6

With marriage as the norm, rural Texans viewed being an “old maid” as a highly undesirable fate, and community amusements reflected this distaste. William Owens recorded a song called “The Old Maid,” which he classified as a humorous work. The song was known throughout Texas, and it classified an old maid’s objections to all of her possible suitors:

I would not marry a man that was tall

For he’d go bumping against the wall;

I’ll not marry at all, at all,

I’ll not marry at all.

Chorus: I’ll take my stool and sit in the shade

I’m determined to live an old maid.

I’ll not marry at all, at all,

I’ll not marry at all.

I would not marry a man that preaches

For he’d have holes in the knee of his britches;

I’ll not marry at all, at all,

I’ll not marry at all. (Chorus)

I would not marry a man that was small,

For he’d be the same as no man at all;

I’ll not marry at all, at all,

I’ll not marry at all. (Chorus)

I would not marry a man that was rich,

For he’d get drunk and fall in the ditch;

I’ll not marry at all, at all,

I’ll not marry at all. (Chorus)

The song could have an infinite number of verses, with local variations in names and situations. It declares the peculiarity of a woman who chooses not to marry, especially with her superficial reasoning and scorn for virtually all types of men. The willingness to “sit in the shade,” out of the sunlight of a nuclear family, marked the old maid’s withdrawal from the mainstream of society. The classification of this song as humorous demonstrates just how ridiculous people of the Blacklands found the option not to marry.7

Emma Guest Bourne remembered a school program from her childhood in the 1890s in the Detroit community, Red River County, called “The Old Maid’s Convention.” The program served as a warning to the young girls taking part in it: “There were about twenty of us girls dressed like the old maids of many years ago. We were bemoaning the fact that we were old maids and there seemed no chance for our ever capturing a husband.” The “old maids” were approached by a man who introduced himself as “Mr. Makeover,” explaining that “he had a machine that would turn us old maids into pretty young girls.” One by one, the old maids entered a “large box-like contraption with a handle which he could turn at will.” When the first old maid emerged from the box, she had become a “changed being, dressed in a beautiful long flowing costume of soft, pale, blue, material, followed by the others in succession dressed like the first.” Professor Makeover then played a march on his machine and the young girls showed their appreciation “by marching in circles around him singing joyful songs.”8 Bourne’s guileless recollection of “The Old Maid’s Convention” many years later indicates that the community apparently recognized easily the stereotypical character of the ugly old maid. The people of Detroit received unquestioningly, under the auspices of an educational institution, a performance in which a single male character could turn a handle “at will,” save an entire group of young women from the awful fate of being unmarried, and then get them to march to a tune of his own playing.

Most young people, then, entered their teens expecting to find their life mates within a few years, and courting rituals enabled them to mingle with possible partners. Young Anglo-Americans met at group activities such as community singings or play-parties, carefully chaperoned by older family members and neighbors. As historian Nancy Grey Osterud has pointed out, meeting in community settings provided young couples with chances to get to know one another without appearing too obvious.9 Lucille Mora Perkins and her future husband, Louis John Perkins, “the catch of the community,” courted through community activities in 1916 and 1917:

On Sunday evenings, we had singing. … Every Sunday, we’d go to a different home, in the evening from possibly, say, seven o’clock on to about nine o’clock or ten o’clock, depending. Then we didn’t have cars. We had buggies and horses. So I had met Louis at the church that day and, of course, he wanted to know if we could go to a singing that night. I said, “By all means. Sure. We’ll go singing.” So here he comes with his buggy and horse. That buggy was shined up. It was just sparkling. … So really, that evening, then about 6:30, 6:45, we went to the singing. We had a piano, organ, wherever we were going. … Of course, there is where I met so many of the people, you see. So from then on it was almost a regular thing.10

After the group activities, buggy rides provided a place of privacy for a couple that rarely existed in parents’ small houses with many siblings or in a home where the teacher boarded. According to Frank Locke, strict rules governed the buggy rides; the couple had to be going somewhere, with a “specified and approved destination.” In some locales, couples could ride together for pleasure on Sundays only.11

Bernice Porter Bostick Weir met her first husband, Pat Bostick, at a party in 1916, but their courtship was altered by a new invention, the automobile:

Well, my uncle that lived down here in the Liberty Hill community—he had the girl that’s my age—and I’d come up here and they had lots of parties up here at night where the whole family would go, the mother and the daddy. Well, I’d come up to Uncle Bruce’s, and he’d hitch up to the wagon and we’d all go wherever the party was. Everybody else was that way. And so I met Pat at a party. But the first time I ever went with him, I didn’t have a date. He had Grandma’s car, a little Ford. And we’s up here at church. And he and Lilburn Newman, which was a neighbor there—they were real close and went with different girls together—Lilburn never had any way to go and Pat did, you see. And so Pat was with Sadie and I was supposed to go with Lilburn. And when we went to get in the car, Pat grabbed me and put me on the back seat and Lilburn and Pat’s girlfriend had to get on the front seat. And that was our first date together.

As the owner of the car, Pat Bostick pressed his material advantage to persuade his male friend to switch dates with him: “He told Lilburn he could drive. Lilburn loved that because he didn’t have a car to drive at home.” He used his physical advantage to “grab” young Bernice and place her where he wanted her. Pat Bostick may also have employed the age difference to persuade his future bride to join him; she was barely sixteen, and Pat was twenty-four: “I considered him a man and I was just a little girl.”12

Several studies have shown that the rules of courtship changed with the coming of the automobile. As a young woman wrote to a male companion in 1923, “You can be so nice and all alone in a machine, just a little one that you can go on crazy roads in and be miles away from anyone but each other.”13 In the Blackland Prairie, parents tried to counteract the effects of the car by retaining an amount of control over the young, unmarried adults’ activities: “You’s supposed to come in at a certain time, of course, which we always did, it seemed to me like,” Myrtle Dodd said. “We’d always talk to Mama about where we’s going and where we expected to get back to. And when we started going to Waco to the show, that’s pretty bad if you—they probably set up and worried till you got back.”14

Young Roman Catholic men of Czech descent used a ritual method of showing their approval of chosen young women. A series of washing ceremonies took place around Easter, indicating the beginning of courtships. On the day after Easter, Mary Simcik recalled, “the young men would go and wash the eligible girls’ faces. If you were lucky he would come early Monday morning while you were still in bed and wash your face.” This action would “show that they were stuck on the girl, to show his affection.”15 In some areas, the young men washed the women’s faces on Easter morning, and the young women in turn washed the men’s faces on the day after Easter.16 Around the community of Wes...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Fertile Ground, Narrow Choices

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Women, Daughters, Wives, Mothers

- Chapter Two: Keeping Warm, Keeping Dry

- Chapter Three: Living at Home

- Chapter Four: Making a Hand

- Chapter Five: Life Beyond the Farm

- Chapter Six: Staying or Going

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index