- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In 1890, more than 100,000 Welsh-born immigrants resided in the United States. A majority of them were skilled laborers from the coal mines of Wales who had been recruited by American mining companies. Readily accepted by American society, Welsh immigrants experienced a unique process of acculturation. In the first history of this exceptional community, Ronald Lewis explores how Welsh immigrants made a significant contribution to the development of the American coal industry and how their rapid and successful assimilation affected Welsh American culture.

Lewis describes how Welsh immigrants brought their national churches, fraternal orders and societies, love of literature and music, and, most important, their own language. Yet unlike eastern and southern Europeans and the Irish, the Welsh — even with their “foreign” ways — encountered no apparent hostility from the Americans. Often within a single generation, Welsh cultural institutions would begin to fade and a new “Welsh American” identity developed.

True to the perspective of the Welsh themselves, Lewis’s analysis adopts a transnational view of immigration, examining the maintenance of Welsh coal-mining culture in the United States and in Wales. By focusing on Welsh coal miners, Welsh Americans illuminates how Americanization occurred among a distinct group of skilled immigrants and demonstrates the diversity of the labor migrations to a rapidly industrializing America.

Lewis describes how Welsh immigrants brought their national churches, fraternal orders and societies, love of literature and music, and, most important, their own language. Yet unlike eastern and southern Europeans and the Irish, the Welsh — even with their “foreign” ways — encountered no apparent hostility from the Americans. Often within a single generation, Welsh cultural institutions would begin to fade and a new “Welsh American” identity developed.

True to the perspective of the Welsh themselves, Lewis’s analysis adopts a transnational view of immigration, examining the maintenance of Welsh coal-mining culture in the United States and in Wales. By focusing on Welsh coal miners, Welsh Americans illuminates how Americanization occurred among a distinct group of skilled immigrants and demonstrates the diversity of the labor migrations to a rapidly industrializing America.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Welsh Americans by Ronald L. Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1: Emigration, Immigration

Americans and Welshmen think of the industrial migration of the mid-to-late nineteenth century as the historical tissue connecting the two nations, but the links actually stretch back to the origins of the United States. Although an indeterminate number of Welsh went to the American colonies, they were few in number and they went as individuals. This changed with the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 when a significant number of Quakers, Baptists, and Presbyterians departed for the New World. The victory of Oliver Cromwell and the Protestants over the royalists in 1645 during the first civil war stimulated the growth of Protestantism in Wales. The inability to preach in the Welsh language also rooted out many Anglican clergy, further weakening the power of the established church in Wales. Restoration of the British monarchy, however, threatened the Nonconformists with persecution, and emigration became an avenue of escape.1

The first individuals to migrate to the American colonies were led by the Swansea Baptist, John Miles, who led his congregation to New England in 1663. Finding the Plymouth Puritans too repressive, he established the permanent and prosperous colony of Swanzey in Rhode Island. Other Nonconformist groups motivated by similar pressures created by the Restoration soon followed. The first major Welsh migration to Pennsylvania came with the Quakers and Baptists from northern and western Wales, who settled on William Penn’s lands. Penn himself thought about naming the colony “New Wales,” but Charles II, who granted the charter, christened it “Pennsylvania.” Hoping to attract Welsh Quakers, Penn agreed that a large forty- or-fifty-thousand-acre tract known as the “Welsh Tract” (present-day Bala Cynwyd) would be set aside for the Welsh to control. Led by Richard Davies, the first group of Welsh sailed for Pennsylvania in 1682, and many more followed. The migrants were disappointed, however, when Penn surveyed the Welsh Tract and divided it into townships. Whatever hope remained for establishing a Welsh domain were put to rest in 1691 when the Welsh Tract was opened to non-Welsh settlers. Welsh Anglicans and Welsh Baptists were also attracted to Pennsylvania. The Baptists’ tendency to splinter soon overtook them, and in 1703 those who wanted services in Welsh split from those who did not and moved to the Welsh Tract near present-day Newark, Delaware. Another group established a colony along the Black River in North Carolina in the 1730s, and a third established Welsh Neck on the Pee Dee River in South Carolina in 1737. By the 1790s, the inability of the Welsh to maintain compact ethnic settlements, the drying up of new immigrants from Wales to replenish the culture, and the economic advantages of assimilation led to the decline in Welsh language and customs in the American colonies.2

It would be natural to attribute the motives of these early emigrants to rural poverty and agricultural distress, for both were plentiful, but most of them were people with some means. Moreover, they had a broader political and religious consciousness than is generally ascribed to peasants. Several prominent Nonconformist clergymen with a wide following in Wales and a deep understanding of American affairs embraced the American War for Independence and took the lead in defending it from opponents in Britain. In his Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty (1776), the dissenter Richard Price anticipated Thomas Paine’s application of the “rights of man” to the Revolution, and David Williams, another Welsh dissenter who knew Benjamin Franklin, advanced an intellectual defense of the Americans in Letters on Political Liberty (1782). Both argued for the God-given right to national self-determination, and Williams went a step further by advocating universal manhood suffrage, the ballot, payment of MPS, annual parliaments, and smaller constituencies—reforms that presaged the Chartist Manifesto. The identification of America with radical democratic ideals had a strong appeal in Wales, particularly coming from these highly respected religious leaders, and while they did not stimulate emigration, they did keep America in the collective thought as a legitimate alternative for Welsh settlement.3

Welsh emigration in the nineteenth century was divided into two phases characterized by occupation, first an agricultural migration from 1815 to the 1840s, and then an industrial migration from the 1840s to the 1920s. The Welsh agricultural migration was generated by major social and economic changes on the land similar to those stimulating the mass migrations in Europe following the Napoleonic wars. For most of the nineteenth century, Wales was two nations, according to historian Alan Conway. The rural areas were occupied by a “Welsh-speaking, non-conformist, politically Liberal Welsh peasantry and an English-speaking, Anglican, politically Tory landowner class.” In the industrial districts “the same linguistic, ethnic, religious, and political differences divided the foundry men from the ironmasters.” This was more or less true for the colliers as well, who were employed in the captive mines belonging to the iron companies, but less so in the sale-coal segment of the industry where more Welshmen could be found among the owners. Nevertheless, in the heavily capitalized segments of the iron and coal district of South Wales, the Royal Commission on the State of Education in Wales emphasized this division in 1847: “In the works the Welsh workman never finds his way into the office. He never becomes either clerk or agent.… Equally in his new, as in his old, home, his language keeps him under the hatches, being one in which he can neither acquire nor communicate the necessary information. It is a language of old-fashioned agriculture, of theology and of simple rustic life, while the entire world about him is English.”4

In the early nineteenth century, life in rural Wales remained much as it had been for centuries. People clothed themselves in homemade woolens, their diet was poor, and so was their health. Housing was primitive, with families of a dozen children sharing small cottages with the pigs and poultry. The English village was rare in the rural areas of North and mid-Wales, where the prevailing pattern was scattered farmsteads and squatters occupying the high wasteland. The economy depended upon cattle, sheep, and goats, and, since roads were almost nonexistent, Welsh drovers herded their stock to markets over trails followed by their ancestors since medieval times.5

The agricultural revolution that transformed England in the eighteenth century was slow in coming to Wales. The rugged terrain to the west of the South Wales coalfield was remote from major cities, and landowners with the capital to promote improvements generally were nonresidents more concerned with their English lands, while the resident gentry lacked the capital and landholdings were much smaller. This meant that Wales was unprepared for the great population explosion that began in the early nineteenth century and doubled the population of Wales by midcentury. The enclosure movement disrupted traditional patterns of landholding and land use by changing the rules of the “moral economy,” which gave the poor access to commons they could use to sustain themselves. In Wales the enclosure movement was precipitated by the dramatic increase in the price for corn during the wars with France between 1793 and 1815, which made it attractive to enclose uplands formerly regarded as wastelands suitable only for the poor. The impact was felt throughout the British countryside. In Ireland plots traditionally used by the poor to grow potatoes were fenced off. Welsh farmers removed from the moorland grew into an “army of landless farm laborers” forced to migrate to the burgeoning South Wales coal and iron district, or to immigrate to America where cheap land was available.6

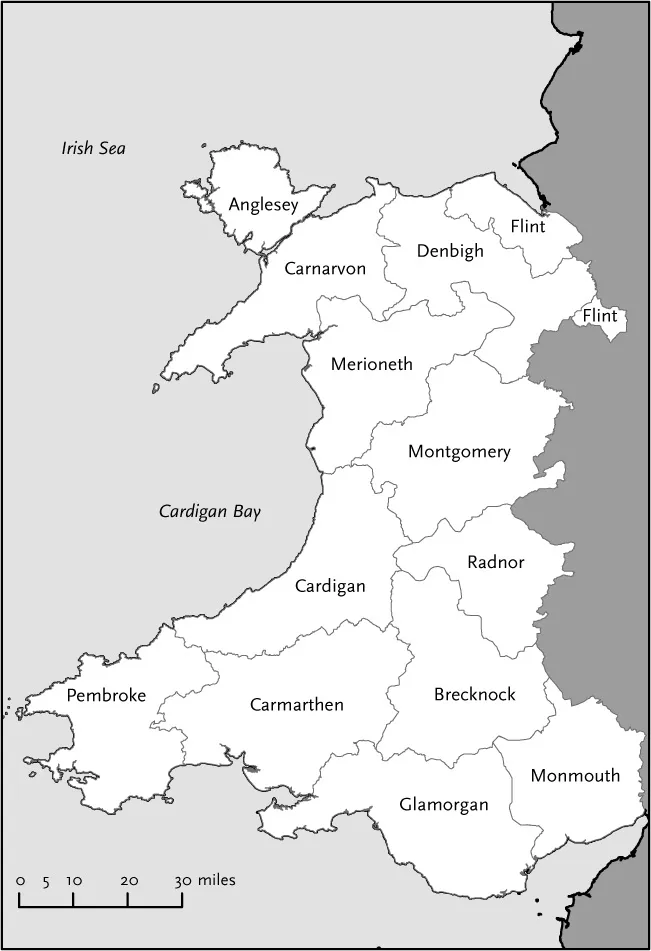

MAP 1. Counties of nineteenth-century Wales. Map by Sue Bergeron, adapted in part from Alexander K. Johnston, England and Wales.

Corn prices collapsed with the end of war, and depression ensued. By 1817 Wales was in the throes of a famine. Although not quite so desperate as in Ireland, the experience in Wales was not entirely dissimilar. The agricultural crisis in Wales was compounded by the government in 1836 when commutation of tithes to money payments became compulsory, an act that was deeply resented in a segment of the population whose religious Nonconformity was becoming nearly universal. To the class and language antagonisms dividing the gentry and tenants was added religion. Like their Irish counterparts, the normally conservative Welsh peasants became radicalized, and their grievances exploded in the Rebecca Riots following passage of the Highways Act of 1835. The act initiated a turnpike system in Wales, maintained by tolls collected at gates erected every few miles. The first riot erupted in 1839 in West Wales and spread to South Wales during the early forties. Like the better-known rural violence of the Whiteboys, Ribbonmen, and Molly Maguires in Ireland, Welshmen with their faces blackened and disguised in women’s clothes destroyed tollgates and drove off the keepers and constables attempting to protect them. Initial success prompted an expansion of the attacks against the barns of grasping landowners and the hated workhouses. By the mid-forties the authorities had stamped out these protests, and the main Rebecca leaders had been transported to the penal colony in Australia.7

The agrarian unrest had major implications, however, as the Welsh became much more politically conscious. The Nonconformist ministers emerged from the smoke of cultural war as the uncontested leaders of the people in the struggle against the Anglican, English-speaking, Tory landowners who still controlled society. The rising tide of Welsh nationalism broke in full force over the “Treachery of the Blue Books” (Brad y Llyfrau Gleision), an inquiry conducted for Parliament by the Royal Commission on the State of Education in Wales and released in 1847. The three commissioners were English Anglicans ignorant of the Welsh language and culture who conducted themselves with an arrogance that exceeded what even the Welsh had come to expect from the English. The reports contained a wealth of social information, but the commissioners managed to insult patriotic Welshmen with their conclusions that the indigenous language, culture, and institutions of Wales were inferior. The most hostile response was prompted by the commissioners’ characterization of rural Welsh women as “almost universally unchaste.” The report was received in Wales with bitter indignation, and galvanized the Welsh behind the Noncomformist ministers who launched a counterattack against English imperialism.8

The “Treachery of the Blue Books” shifted the balance of power in the political struggle for the hearts and minds of the Welsh-speaking Nonconformist ministers who rose up in unison to denounce the Blue Books. Their position was heightened by the great religious revival of 1859, and by the actions of landowners who evicted tenants who refused to become Anglican or to vote for politicians the landowners found acceptable. The politics of dissent attracted some notable candidates into the field during the general elections of 1868. Perhaps most prominent was the election to Parliament of the Reverend Henry Richard of Merthyr, a leading Nonconformist spokesman in Wales and outraged critic of the Blue Books. He and several other dissenters were elected that year, and they brought the issue of disestablishment of the Anglican church as the official state church to the forefront of Welsh politics.9

In this context, one can readily understand why the idea of establishing a new Welsh nation abroad, one that would preserve the language and culture of Wales, gained urgency during the nineteenth century. Nonconformist ministers, such as Morgan John Rhys, Rev. Benjamin Chidlaw, Rev. Samuel Roberts, and Rev. Michael D. Jones, played a prominent role in this movement, leading thousands of Welsh to new colonies abroad. Rhys, a Baptist preacher, began his search for a location for the new Gwalya, or homeland, in the American backcountry in 1794. The new colony, “Beulah Land,” was established in Ebensburgh, Cambria County, Pennsylvania, and hundreds of settlers sailed from Wales over the ensuing decade. Some of them continued down the Ohio River to found sister colonies in southwestern Ohio. One of them, Benjamin Chidlaw, had immigrated to Ohio with his parents as a youth but returned to Wales to complete his education. Shortly after he finished his studies, Chidlaw became the Congregationalist minister at the Welsh settlement of Paddy’s Run (now Shandon), near Cincinnati. He returned to Wales again in 1836 and 1839 to revitalize his command of Welsh and to preach the advantages of colonization. In 1840 he published his widely distributed Immigrant’s Guide to America to help newcomers.10

The Reverend Samuel Roberts of Llanbrynmair, Montgomeryshire, a close friend of Chidlaw, proclaimed that only by immigrating to the United States could Welsh farmers become landowners and preserve the Welsh language and culture. In establishing the Welsh colony of Brynffynon in Tennessee, Roberts received assistance from his cousin William Bebb of Ohio. William was born in 1802 to Edward and Margarett Bebb, who emigrated from Llanbrynmair with the first settlers of Paddy’s Run. Their son William became the first native-born governor of Ohio, serving from 1846 to 1848. Although Roberts’s experiment failed, he was instrumental in creating awareness in Wales of the benefits of emigration through his journal Y Cronicl, and a widely circulated pamphlet in Wales, Farmer Careful of Cil-Haul Uchaf. The third prominent minister seeking to establish a haven for the preservation of the Welsh language and culture was the Congregationalist preacher Michael D. Jones of Bala, Merionethshire. Former governor William Bebb seems to have had some influence on Jones as well. Jones’s sister, Mary Ann, had immigrated to Ohio in the 1830s and grew up in the Bebb household. Bebb encouraged Jones to migrate to Ohio in 1847, but Jones believed that Americanization was too powerful for Welsh culture to survive in the United States, so in 1865 he established a new Welsh colony in the Chubut Valley in Patagonia, Argentina.11 If a separate nation for the preservation of the Welsh language and culture are the only measurement, these colonies failed.

Undoubtedly, the promotional activities of these preachers stimulated interest and general awareness of emigration among the rural Welsh population. The vast majority of those who left for America went for pragmatic rather than idealistic reasons. Even though the vast majority did not seek an exclusive Welsh existence, the pre-1840s agrarian migrants tended to join family and friends in the Welsh agricultural communities of Pennsylvania, New York, and eastern Ohio, where they continued their familiar ways with little interference. Welsh settlers followed the American western agricultural migration into the fertile flatlands of the Midwest. Important Welsh settlements were established early in Ohio’s Western Reserve at Palmyra, and then in central Ohio at Gomer, and in the southern part of the state in Gallia and Jackson Counties, which became known as “Little Cardiganshire.” Continuing the westward migration, large concentrations of Welsh settled in Wisconsin, and others moved to Iowa, Missouri, and Kansas. The Welsh certainly were not averse to being pioneers, but, compared with other immigrant groups, their numbers were small, and the further west they migrated the thinner and more dispersed on the land they became. It is also clear that they emigrated individually or in family groups, relying on family to assist them in settling the new land. One section of the United States Welsh farmers avoided was the South. In 1860 the census reported that fewer than 500 of the 45,500 foreign-born Welsh lived below the Mason-Dixon Line. If the Welsh ethnic press and prominent chapel leaders are an indication, Welsh immigrants avoided the South because ideologically they found slavery repugnant. Solid material reasons also motivated their avoidance, however, for there was little cheap land available in the South, and there was little demand for their labor in a region dependent on oppressed African American workers.12

Occupying a unique place in the history of Welsh emigration in the mid-nineteenth century was the large number of Mormon converts who settled in Utah. I...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Welsh Americans: A History of Assimilation in the Coalfields

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations, Maps, & Tables

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Emigration, Immigration

- Chapter 2: Superintendents, Networks, and Welsh Settlement Patterns

- Chapter 3: Community, Republicanism, and Social Mobility

- Chapter 4: Welsh American Cultural Institutions

- Chapter 5: Professional Inspectors for a Disaster-Prone Industry

- Chapter 6: Ethnic Conflict: The Welsh and Irish in Anthracite Country

- Chapter 7: The Slav “Invasion” and the Welsh “Exodus”

- Chapter 8: Welsh American Union Leadership

- Chapter 9: From Nantymoel to Hollywood: The Incredible Journey of Mary Thomas

- Epilogue: Americanization and Welsh Identity

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index