eBook - ePub

The Art and Science of Aging Well

A Physician's Guide to a Healthy Body, Mind, and Spirit

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Art and Science of Aging Well

A Physician's Guide to a Healthy Body, Mind, and Spirit

About this book

In the past century, average life expectancies have nearly doubled, and today, for the first time in human history, many people have a realistic chance of living to eighty or beyond. As life expectancy increases, Americans need accurate, scientifically grounded information so that they can take full responsibility for their own later years. In The Art and Science of Aging Well, Mark E. Williams, M.D., discusses the remarkable advances that medical science has made in the field of aging and the steps that people may take to enhance their lives as they age. Through his own observations and by use of the most current medical research, Williams offers practical advice to help aging readers and those who care for them enjoy personal growth and approach aging with optimism and even joy.

The Art and Science of Aging Well gives a realistic portrait of how aging occurs and provides important advice for self-improvement and philosophical, spiritual, and conscious evolution. Williams argues that we have considerable choice in determining the quality of our own old age. Refuting the perspective of aging that insists that personal, social, economic, and health care declines are persistent and inevitable, he takes a more holistic approach, revealing the multiple facets of old age. Williams provides the resources for a happy and productive later life.

The Art and Science of Aging Well gives a realistic portrait of how aging occurs and provides important advice for self-improvement and philosophical, spiritual, and conscious evolution. Williams argues that we have considerable choice in determining the quality of our own old age. Refuting the perspective of aging that insists that personal, social, economic, and health care declines are persistent and inevitable, he takes a more holistic approach, revealing the multiple facets of old age. Williams provides the resources for a happy and productive later life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Art and Science of Aging Well by Mark E. Williams, M.D.,Mark E. Williams M.D. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Geriatrics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Aging Secret 1: Appreciate Your Reality

There is no cause for fear. It is imagination, blocking you as a wooden bolt holds the door. Burn that bar.

— Rumi

Don’t judge each day by the harvest you reap but by the seeds that you plant.

— Robert Louis Stevenson

Most of us spend a large portion of our lives seeing older people as “other.” We were all at some point children, so we remember to a certain extent what that was like. As we reach adulthood and journey through middle age, we discover our interests, find an occupation, carve out our niche in the world, and perhaps build a family of our own. Along the way we create identities for ourselves that stem from our roles in the family, workplace, or community. But although we all encounter older people throughout our lives and may have the opportunity to watch loved ones grow into old age, the view of older people as a group different from oneself often remains stubbornly persistent.

The truth is that old age is not some distant place or group of “others” but an integral part of who we are now. The body we reside in today is also our future dwelling place in old age. And at any age we are all people—equally valuable, capable, and worthy. The essence of aging secret 1 is to face the truth that we are likely to grow old and to begin to consider what this means to each of us. In the analogy of the horse, carriage, driver, and master introduced in the prologue to this book, the first step is for the driver to emerge from the tavern and critically examine his own state and that of his horse and carriage. With this examination I hope you will see—perhaps with some relief—that your later years do not have to be marked by deterioration and fear. In many ways, old age can be more a culmination of life than a prelude to death.

Of course, although aging is an intimate, personal process, it does not occur in a vacuum. The larger demographic trends of one’s society and the way in which aged people are perceived and treated greatly influence the experience of growing old. Today the United States, in common with other nations, is undergoing a social revolution—one rooted not in a new ideology but in our changing population patterns. For the first time in history, infants in fortunate nations like ours can expect to live well into their eighties. This demographic revolution increases pressure on resources as it also creates further social change and new opportunities for older people. Many of our deep-seated cultural stereotypes do not describe accurately the “new wave” of elderly people or their potential contributions to society. The next few chapters aim to create a more realistic picture of aging by taking a critical look at the roles, understanding, and perceptions of aging and older people in our society today and in the past.

The central conflict of aging is between you today and you in the future. Who are you becoming? How will you look? What will you be able to do physically and mentally? What goals and projects will you pursue? How will you handle crises? The end of life? From the beginning of history people have asked these questions and have searched for ways to approach the later years with grace—productively, creatively, and with satisfaction. Each of us influences the answers to these questions through the choices we make in earlier years. If you avoid premature death, you are ultimately obliged to live in old age whether you develop a satisfactory image of yourself or not. You have a choice in the attitude you take about your own aging—and that attitude will be a critical factor in your success. The first order of business is to appreciate your reality and develop an understanding of what you can expect as you grow old. Then you can examine for yourself the rich potential of your later years.

Chapter 1: You’ll Probably Grow Old

He who loves practice without theory is like the sailor who boards ship without a rudder and compass and never knows where he may cast.

— Leonardo da Vinci

We must be willing to let go of the life we’ve planned to have the life that is waiting for us.

— E. M. Forster

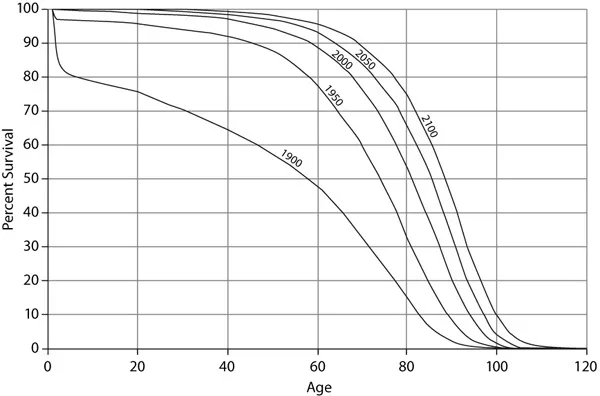

For the first time in human history many of us can realistically expect to live into old age. A baby born today in most parts of America, Europe, and the Pacific Rim has a better than 50 percent chance of living beyond the age of eighty. In Monaco, the country with the most impressive longevity, the average life expectancy at birth is over eighty-nine! If you are already eighty you have a 50 percent chance of reaching ninety. To put these startling statistics in context, consider the fact that during the Bronze Age (about 3000 B.C.) the average life expectancy at birth was eighteen. By the days of the Roman Empire it had risen to about thirty-five. In early twentieth-century America it was only forty-seven. This means it took humankind two millennia to increase average life expectancy by twelve years (from thirty-five to forty-seven). In the last one hundred years the average life expectancy at birth has nearly doubled from forty-seven to eighty.

Our increased longevity has dramatic implications at numerous levels—the individual, the family, the community, and society. Between 1900 and 2012 the percentage of Americans over age sixty-five more than tripled, from 4 percent (3.1 million) to over 13 percent (43.1 million). According to census projections, this population will almost double to reach nearly 80 million by 2040. Moreover, these are not idle speculations—all of the people who will be “old” in the year 2040 are alive today!

Illustration 1. Estimated survival curves for the U.S. population in 1900, 1950, 2000, 2050, and 2100. These curves show how longevity has increased over the years—a trend that is expected to continue in the future. (Social Security Administration, “Life Tables for the United States Social Security Area 1900–2100,” fig. 5, http://www.ssa.gov/oact/NOTES/as120/LifeTables_Body.html)

WHAT DETERMINES LONGEVITY?

Though of course it is impossible to know how long a particular individual will live, we can learn a great deal from studies at the population level. Life course epidemiology is the study of the factors that influence our longevity. Recent research in this field has convincingly shown that the major causes of death—those accounting for about 70 percent of deaths—relate directly to one’s environment, such as having clean air and water, a stable supply of healthy food, and a safe place to rest at the end of the day. This observation appears to be consistent across cultures. The other 30 percent of our mortality hazard relates mainly to our genetics and health-adverse behaviors for specific diseases, such as heart disease.

Which environmental factors are associated with longer life-spans, and which may contribute to premature death? One key feature is socioeconomic status and, more specifically, the income gap between the wealthiest and the poorest members of a society, sometimes called the Robin Hood index. Technically, the Robin Hood index is the proportion of money needed to be transferred from the rich to the poor to achieve equality. However, it is not just the difference between the wealthiest and the poorest that seems to matter but how rich or poor you are relative to others in your specific community. This effect may stem from a sense of “social standing” related to job options, possessions, feelings of inadequacy, and a variety of personal and social factors.

Education also clearly plays a role in determining your socioeconomic status and thus also influences longevity. Another critical factor is job satisfaction. If your boss is a tyrant and your work environment is stressful, your longevity is compromised no matter how much money you make. For example, several studies document that being laid off or experiencing loss of job security is associated with earlier death, often from heart disease.

Living with a loving partner extends longevity. Caring for a pet also confers a salutary effect. On the other hand, activities such as smoking can accelerate aging of the skin, heart, lungs, blood vessels, and bone and can cause cancer, resulting in premature death. A great many environmental factors also affect quality of life but do not necessarily affect longevity. For example, excessive noise affects the ears, and ultraviolet light ages the eyes and skin. The following chapters explore the ways we can influence our environment for the benefit of both our longevity and our quality of life.

WHAT DOES “REDUCING YOUR RISK” REALLY MEAN?

In addition to identifying broad associations between life-span and environmental factors, epidemiology can also help us connect specific causes of death with their associated risk factors. The technical term for these studies is “proximate cause epidemiology.” Let’s take cardiovascular disease (also called heart disease) as an example. As the number one cause of death worldwide, cardiovascular disease has been extensively studied. Its well-recognized risk factors include age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, high cholesterol, smoking, and family history, among many others. What you may find surprising is that modifying these risk factors (at least those that are under one’s control) may reduce a person’s likelihood of dying from heart disease, though probably not by very much. More telling, modifying these risk factors has little or no effect on mortality. In other words, we may be able to change the likely cause of our death without meaningfully lengthening our lives. Consider which matters more to you: what your death certificate will ultimately list as your primary cause of death, or the ability to have a meaningful life as long as it lasts.

A lot of risk factor modification is much ado about the trivial. If we carefully examine the mountains of scientific evidence, it becomes clear that the impacts are typically on the order of absolute reductions in deaths of 0.5 to 2 percent. In other words, fifty to two hundred people need to be treated over extended periods of time (a decade or so) to prevent one premature death (that otherwise would not have occurred). Realistically, an intervention such as aggressively treating high blood pressure might reduce an otherwise normal individual’s risk of a bad outcome such as a stroke or heart attack from 5 percent to 3 percent, a 2 percent reduction over five to ten years.

It is easy to be confused about risk factor modification by what we read or hear in the media. Absolute risk reduction, the difference between our baseline risk and the reduced risk with the intervention, is what really matters. But clinical studies and the media frequently trumpet relative risk reduction, which is the percentage your risk has been reduced. In the example above for treating hypertension, the relative risk reduction would be a 40 percent drop in the risk from 5 percent to 3 percent. Which sounds more convincing, “We can reduce your risk of a stroke or heart attack by 40 percent” or “We can lower your absolute risk of a stroke or heart attack by 2 percent (or one in fifty)”? These statements are mathematically equivalent.

YOU STILL CAN’T LIVE FOREVER

Despite recent gains in longevity, the death rate has held steady at one per person (it has remained remarkably constant for millennia). Although you are likely to attain old age, living indefinitely is not an option. The implication of our inevitable mortality is that the nature of life’s journey becomes more important than its length. And the good news is that a wealth of scientific evidence shows that we can significantly influence the quality and possibly the rate of our aging.

The target of modern preventive health care is to extend longevity by reducing premature death, which certainly seems reasonable in very young populations with many decades of remaining life. However, defining “premature death” becomes increasingly problematic the older we become and ultimately misses the point because the death rate is still one per person. It is my view that at some stage of life the target of prevention needs to shift from maximizing longevity to maintaining function and minimizing dependency. As we live longer and better, we should focus on those factors that threaten our independence, such as problems of vision, hearing, mobility, and memory. As a geriatrician I tell my very elderly patients that my goal is to keep each of them smiling and happy for as long as possible. So far, no one has voiced a different objective.

WHAT DOES OLD AGE MEAN TODAY?

Old age, once the privilege of the very few, has become the modern destiny for most of us. This is a monumental achievement of the twentieth century that ranks with placing a man on the moon, advances in telecommunication, splitting the atom, and unraveling our DNA. But where is the celebration? No one seems to appreciate the truly historic human accomplishment of unprecedented life expectancy.

Our rapid demographic changes have left most of us living in the past in our generally negative attitudes about aging and elderly people. The same outmoded beliefs are embedded in many of our social programs. In our youth-oriented culture, most of us still view old people as physically decrepit or in rapid and inevitable decline. Mentally they are viewed as forgetful or childish, with little ability to learn and adapt. Socially and economically they often are considered a burden. With such stereotypes, where is the expectation and encouragement for the continuing capacity of elderly people to enrich their own lives and to enrich society?

Chronological age has virtually lost its meaning as a useful index of individual capacity. Today’s aging Americans are typically far from decrepit. Less than 25 percent of them experience any significant disability and less than 5 percent are in nursing homes. Intellectually, when they take advantage of new opportunities to learn and grow, they thrive. With suitable occupation they work with zest and competence well beyond the traditional age of retirement. Many have an emotional maturity and the kind of wisdom that come only with age and having experienced life in all of its phases.

To be sure, many old people have special needs for health care and other supports. But these cannot be provided competently without abandoning the old stereotypes and without a broader public understanding of today’s elderly population and its relationship to the rest of society. A humane society respects the special character inherent in every stage of life and in every person. We need to take a closer personal look at growing old, and we need to redefine the meaning of later life in our society. This vital redefinition requires public discussion that takes advantage of historical and cross-cultural perspectives, as well as research on aging in the biological and social sciences. This discussion begins with each of us as we face our own aging and consider the future we want to create.

Chapter 2: Eight Aging Myths You Don’t Have to Fall For

Myths which are believed in tend to become true.

— George Orwell

It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data.

— Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

A well-known parable describes a university professor who went on a pilgrimage to visit a famous Zen master. While the master quietly served tea, the professor talked about Zen. The master poured the visitor’s cup to the brim, and then kept pouring. The professor watched the overflowing cup until he could no longer restrain himself. “It’s overfull! No more will go in!” the professor blurted. “You are like this cup,” the master replied. “How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?” In the same way, we need to empty ourselves of myths and misinformation on aging so that we can appreciate the reality of our situation. Let’s examine some of the more destructive aging myths so that we can more accurately plan for and embrace the aging process.

MYTH 1: ALL OLDER PEOPLE ARE BASICALLY THE SAME, AND THEY ARE FALLING APART

This myth stems from a view of older people as “other” and is reinforced through caricature depictions such as those you might find in television commercials. In reality, as we age we actually become more unique and differentiated, more individualized, and less like one another. None of us ages in exactly the same way, and each of us ages at a different rate. Anyone who has attended a class reunion can verify that some classmates seem to have aged very little over the elapsed time while others seem to have grown considerably older. So we may see one elderly person with bright eyes and sagging muscles and another with creaking joints and an active mind.

The physical changes that accompany aging depend on a cluster of interrelated biological circumstances rather than a single dominant factor. Aging represents interactions among our unique genetic endowment, environmental factors that are largely outside our control, and factors that result from the choices we make. These choices may accelerate or retard the progression of physical change. For example, cigarette smoking appears to speed up aging of the lungs, heart, and blood vessels, in addition to substantially increasing the risk of cancer. Getting regular exercise, on the other hand, can slow the aging process by stimulating the body’s ability to repair itself.

On the whole, people today are not only living longer but aging better. Longitudinal studies from the United States, Sweden, and other countries show continued improvements in the health status of people sixty-five and older. The results show, for example, that a seventy-five-year-old person in 1990 was roughly the biological equivalent of a sixty-five-year-old in 1960. Such findings also confirm th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Art and Science of Aging Well

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue: A Parable and a Framework for Aging Well

- Aging Secret 1: Appreciate Your Reality

- Aging Secret 2: Challenge Your Body

- Aging Secret 3: Stimulate Your Intellect

- Aging Secret 4: Manage Your Emotions

- Aging Secret 5: Nurture Your Spirit

- Notes

- Index