![]()

Chapter 1: God May Choose a Country Boy

William Rohl Bright was born on 19 October 1921, the sixth child and fifth son born to Forrest Dale and Mary Lee Rohl Bright. Since her last pregnancy had ended in a stillbirth, Mary Lee worried that she would not be able to carry her next child to full term. When she became pregnant again, she “made a commitment to God that the next child would be dedicated to him.” Earlier that year, the Brights had settled on a ranch located on the outskirts of Coweta, Oklahoma. Coweta was—and still is—a small town situated on the railroad line running southeast from Tulsa to Muskogee. Sam Bright, Bill Bright’s grandfather, had made a small fortune in the Oklahoma oil business shortly after the federal government officially opened the old Indian Territory to white settlement. Aiming to provide his children with a source of stable income, he bought sizable ranches for Forrest Dale and his other three sons. Dale, as he was known, occasionally bought and sold horses and other livestock, but cattle were the heart of his ranching operation. He employed several hired hands, who helped the family raise cattle and grow crops for feed. Although the Brights never became wealthy, they were prosperous by comparison with most Coweta families.1

As a child, Bill Bright’s main activities were ranching and reading. His first chores were collecting eggs and gathering dry corncobs and wood to heat the family’s stove. Throughout his entire childhood, the ranch did not have electricity, but running water was provided by a windmill that pumped water into an elevated tank, from which it was fed by gravity into the house. The family installed gas lights after Dale Bright hit gas while drilling for oil on the property. As he grew older, Bill Bright “took his place alongside his four brothers and other hired men in milking the cows, feeding the hogs, caring for the horses and cattle, working in the fields, plowing, cultivating, harvesting, threshing the grain and baling hay for the cattle.” The family rose well before sunrise each morning, and the boys took kerosene lanterns to the barn to milk the cows and feed the hogs and chickens before breakfast. The Brights cranked their own cream and on Saturdays traveled by horse or wagon on the narrow five-mile gravel road that led to Coweta, where they traded eggs and cream for groceries and other necessities.

Mary Lee had taught school briefly before marrying Forrest Dale, and she devoted herself to her children’s intellectual formation, instilling in them a love for literature and books. On days when it was his responsibility to herd cattle, Bright would put a book in his saddlebag and read “whenever precious moments allowed.” “There are also vivid recollections,” he wrote about days devoted to reading, “of those special days when in the providence of God it rained, and it was impossible to work outside.” In the evenings, Mary Lee would read to the family Walter Scott novels and poetry by James Whitcomb Riley, a distant cousin and popular early-twentieth-century poet. Bright’s mother, who had a conversion experience in a Methodist church at age sixteen and whose brother became a Methodist minister, read her Bible every morning and evening, sang hymns while doing housework, and took her children to Coweta’s Methodist Church. “I can remember seeing her kneeling at her bed and praying,” remembers Charley Bright, Bill Bright’s nephew who came to live with his grandparents in 1935. Bill Bright later recorded that his mother “gathered the children of neighborhood families together in her home to teach the Bible.” Following her example, he joined the Methodist Church at the age of twelve. Bright always maintained an especially close relationship with his mother, whom he would later refer to as his “saintly mother” or “Godly Christian mother.” “When it came to his mom,” comments Bright’s own son Brad, “there was a spot in his heart that nothing else could touch.”2

Bright’s father was hard-driving, domineering, and less pious than his wife. When Mary Lee disciplined her children, she sent them to bed. Dale employed the “strap.” He expected his children to follow his instructions. “He was always the boss in any circumstance,” comments Charley Bright. Dale would sometimes escort Mary Lee to church, but often he would only bring her to the church door and then find somewhere in Coweta to talk business and politics. He was active in local and county Republican politics and at one point became chairman of the Wagoner County Republican Party. During these years, the Oklahoma Republican Party displayed a Protestant commitment to Prohibition, probusiness sentiment (partly due to the strength of the state’s oil lobby), vitriolic opposition to the New Deal, and almost complete political impotency.3 Dale Bright’s partisan affiliation was unusual for his environs, as Coweta, like most of Oklahoma, was solidly Democratic territory. Partly because of that political reality, Dale would “usually get in a fight on election day.” Bill Bright never deviated from his father’s choice of political parties, and as a boy and young man he sometimes envisioned a career in politics. He also absorbed his father’s indifference to religion. Given the spiritual dynamics of his own family, Bright later wrote that he “thought Christianity was for women and children but not for men.”4

After eight years in a rural “one-room schoolhouse,” Bright attended Coweta’s high school. While the Works Progress Administration completed a new building, the school’s lower grades met in church basements and classrooms. Most of the school teachers also taught Sunday school in Coweta’s churches, and school days included a blend of Christianity and patriotism alongside reading, writing, and arithmetic. Curtis Zachary, Bright’s brother-in-law, describes the atmosphere at Coweta’s school. “You had prayer in schools, you sure did,” Zachary remembers, “and the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer and oftentimes individual prayer … even in high school.” “We would always sing the Star Spangled Banner and have a flag salute,” Zachary continues, “and then the pastor would give an invocation.”

Alongside thirty-two classmates, Bright graduated in 1939. He enrolled at Northeastern State College in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, a former normal school that still primarily trained teachers. Now anticipating a career in medicine, Bright explored other academic options after he earned a C in chemistry during his first semester.5 A solid B student for the rest of his collegiate years, Bright juggled academics, social events, several part-time jobs, and extracurricular activities with the boundless energy he would maintain for most of his life. He pledged the Sigma Tau Gamma fraternity chapter, performed in plays, and won first prize in an intercollegiate Prohibition oratorical contest sponsored by the Anti-Saloon League. In his junior and senior years, respectively, Bright served as student body vice president and president. He also managed to find time to enjoy campus social life, attending and organizing several dances during his years in Tahlequah. In the spring of 1941, he drummed up publicity for Northeastern’s annual Sadie Hawkins dance; the Northeastern, the college’s newspaper, described Bright’s ideal consort as a “tall, lean freckled thin girl.” He also cooked, waited tables, and washed dishes in the college dining hall to pay for his meals, cleaned a dormitory to pay for his room, and became the campus representative for a local laundry and dry cleaner. He neither attended church nor gave much thought to religion. “There was no challenging Christian organization on campus,” he later lamented, and he was “not disposed to seek such fellowship in the local churches.”6

By 1942, the headlines of the Northeastern reported on Tahlequah students and alumni serving in the armed forces during the early months of American involvement in World War II. In November, Bright enlisted in the naval reserve and planned to assume active duty status following his graduation the following May. He left Northeastern with a bachelor’s degree in education and considered becoming a rancher, lawyer, and politician after the war. There were only nine men among Northeastern’s thirty-six graduating seniors in 1943. After he graduated, Bright learned that a burst eardrum he had sustained playing high school football rendered him ineligible for military service. While three of his brothers and a brother-in-law served in the military, Bright returned home to Coweta. Oklahoma A&M College hired him as an agent for Muskogee County, and Bright traveled around his home county meeting with farmers and agricultural students to discuss state and national programs on such topics as commodities futures and fertilizers. Perhaps because he was missing out on the war and unsure of his future vocation, Bright decided to search out new horizons. Like many other Oklahomans in the 1930s and 1940s, he moved to California.7

Bright’s early years in Oklahoma left enduring marks on his outlook and personality. He was always reserved in personality and demeanor, suspicious of intellectuals from elite universities, and devoted to small-town “values.” Admiring the success of his grandfather and father in the oil and ranching businesses—and adhering to his father’s politics—Bright maintained a lifelong commitment to free markets and small government. Ironically, even though Bright claimed to have had no personal Christian faith as a young man, he clung to the way Coweta’s public schools combined faith, patriotism, and education. For example, Bright later traced America’s ills to the early 1960s Supreme Court decisions that ruled that public schools could not lead students in prayer and other religious devotions. Several other leaders of the evangelical movement that emerged after the war came from small towns across the American South and Midwest, many of which roughly resembled Coweta. Billy Graham grew up on a farm outside Charlotte, North Carolina, Oral Roberts on the Oklahoma sawdust trail, and Rex Humbard near Little Rock. Jimmy Swaggart, Jim Bakker, and James Robison—all younger than Bright—haled from the backwaters of the American South and Midwest. Pat Robertson, though he experienced a more cosmopolitan upbringing as the son of a U.S. senator, spent much of his childhood in rural Virginia. By contrast, the very first cluster of evangelical leaders in the 1940s had come from major metropolitan centers: Harold Ockenga from Chicago and Carl F. H. Henry from New York City. The rising generation of evangelical leaders—Graham, Bright, and Roberts—displayed a fascination with modernity, particularly with technology and popular culture. Yet their conception of what America should be always remained linked to the small towns and farms where they had come of age.

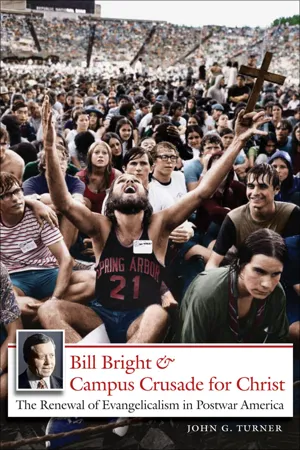

Bill Bright as a student at Northeastern State College, 1942. Courtesy of the Northeastern State University Archives, Tahlequah, Okla.

Mears Christianity8

When Bright arrived in Los Angeles in 1944, he again sought entrance into the military. He knew that another rejection was a distinct possibility, but he had also come to California with other aspirations. “There were several career options open to me,” Bright later chronicled, “but the most attractive was a move to Los Angeles.” Richard Quebedeaux, who wrote a biography of Bright in the 1970s, suggests that Bright was simply another Oklahoma migrant seeking wealth in the Golden State during an explosive wartime boom. “He was seeking his fortune,” confirms Bright’s friend Esther Brinkley. An admirer of Clark Gable, Bright planned to seek acting jobs in local theaters. He hoped to make money quickly and parlay his fortune into a political career.9

Bright, who at the time had no particular interest in religion, met several fervent Christians on his first night in Los Angeles. As he drove around town, he picked up a young man thumbing a ride. The hitchhiker worked for the Navigators, a ministry founded by Dawson Trotman in 1933 that evangelized servicemen, involved them in Bible studies, and encouraged them to memorize large caches of Bible verses. The Navigator brought Bright to Trotman’s home, where Bright received an invitation to spend the night. After dinner, Bright accompanied his hosts to a birthday party for Dan Fuller, the son of the famous radio evangelist Charles Fuller, whose Old-Fashioned Revival Hour was among the most popular radio programs in America.10

Spiritually unchanged from these encounters with Bible-believing Christians, Bright visited the local draft board but was again disqualified because of his burst eardrum. He worked for a short time as an electrician’s assistant for a contractor at a local shipyard but quit when he ascertained that his employer was billing for unperformed work. A new friend invited him to become a partner in a specialty food business, and after several weeks Bright bought out his friend and established Bright’s Epicurean Delights, later renamed Bright’s California Confections and Bright’s Brandied Foods. Initially, the business was successful. Since wartime rationing had largely eliminated the chocolate industry, Bright’s confections—containing, he once told a reporter, “brandy by the hogshead”11—sold well and caught the notice of distributors and department stores, such as Neiman-Marcus and B. Altman. Bright soon drove a convertible and had enough money for fine clothing and horseback riding in the Hollywood Hills. He rented an apartment from an elderly couple in Hollywood, undertook an amateur radio spot, and studied drama at the Hollywood Talent Showcase.

Bright’s landlords attended the First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood, and they encouraged their new tenant to join them on Sundays. In the 1940s, Hollywood Presbyterian was the nation’s largest Presbyterian church, and it attracted upwardly mobile businessmen and Hollywood stars. Lauralil Deats, daughter of Louis H. Evans Sr., then Hollywood Presbyterian’s pastor, recalls “millionaires falling out of every pew.” Bright’s landlords introduced him to affluent businessmen who both modeled the life of material success that Bright desired and simultaneously insisted that a relationship with Jesus Christ was more important than worldly wealth and success. Initially reluctant, he eventually sampled a few services at the church, where he listened to the preaching of Evans and the Bible teaching of Henrietta Mears. One of the young women from Mears’s thriving “College Department” invited Bright to attend a party held at the ranch of a movie star, and, impressed with the caliber of young people at the gathering, he began attending the church on Sundays and Wednesday evenings. The testimonies of these Christian peers and the evangelistic Bible lessons of Mears agitated Bright spiritually and convinced him to investigate scriptural accounts of Jesus Christ. One night Mears taught a lesson on the eighth chapter of Acts, which chronicles Paul’s conversion experience on the road to Damascus. Mears encouraged her listeners to return to their homes, get on their knees, and pray as Paul had done: “Lord, what wilt Thou have me to do?” Bright followed Mears’s advice and later identified this moment as the first major spiritual turning point in his life. “The dollar was no longer his [Bright’s] god,” he later wrote in an autobiographical account, “the materialistic philosophy had been abandoned for the Christ Who died for his sins.” Bright experienced no “cataclysmic emotion,” but he was convinced that Jesus was the son of God.12

Henrietta Mears exerted a strong influence on Bright’s theology and the later shape of Campus Crusade for Christ; hence, it is necessary to explain at some length the shape and significance of her ministry at Hollywood Presbyterian. Reared in fundamentalist kingpin William B. Riley’s First Baptist Church of Minneapolis, Mears taught high school chemistry following her graduation from the University of Minnesota. She also remained active at First Baptist, where scores of high school girls attended her Bible study class. In 1928, Hollywood Presbyterian’s minister, Stuart MacLennan, recruited Mears to be his church’s director of Christian Education, and within a few years several thousand children and adults attended the weekly programs she organized. Mears herself taught the College Department, which by the mid-1930s attracted several hundred young adults to a mixture of Bible teaching and social events. She encouraged her “boys” to become ministers, and she soon had a network of College Department alumni installed in Presbyterian pastorates across California. During the 1930s, Mears also launched two ventures that established Hollywood Presbyterian as a regional fundamentalist force. She wrote her own age-graded Sunday school curriculum and founded Gospel Light Press to publish it. Gospel Light became one of the most popular publishers of fundamentalist Sunday school curricula. Charles and Grace Fuller joined Lake Avenue Congregational Church in large measure because they respected its Christian Education Department, which used Mears’s materials. In 1938, Mears arranged the purchase of Forest Home, a resort in the San Bernardino Mountains, which she turned into a Christian retreat center. Forest Home became an important conduit for fundamentalist networking and growth in Southern California, as “Forest Home churches” of various denominations sent delegates to retreats and teacher training conferences organized and often hosted by Mears.13

Mears’s career illustrates both the possibilities and limitations women encountered when they pursued careers in ministry within the context of midcentury fundamentalism. Mears, who was single and lived with her sister Margaret, worked hard to avoid transgressing fundamentalist gender norms. She officially served under a male superintendent and insisted her expository lessons were “teaching” rather than “preaching.” Yet adherence to such standards masked her true authority and power. Her superintendent was a figurehead, and Mears ran the church’s Christian Education program, Gospel Light Press, and Forest Home. Mears always served under male pastors who were renowned in their own right, but those connected with the church in these decades recall her as “the power behind the throne.” “All the elders of the church and all the pastors of the church were men,” explains longtime Hollywood Presbyterian member Anna Kerr, “and there were forty-five men on the session that seemed to be all delighted to eat out of her hand.” With the prominent exception of herself, Mears wished to preserve traditional patterns of gendered leadership in the church. Citing the church’s difficulty in attracting sufficient numbers of men, she claimed to select women as leaders as a matter of last resort. She argued for this course not as a matter of doctrine or Scripture but on the basis of pragmatic expedi...