eBook - ePub

Gender and the Mexican Revolution

Yucatán Women and the Realities of Patriarchy

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The state of Yucatán is commonly considered to have been a hotbed of radical feminism during the Mexican Revolution. Challenging this romanticized view, Stephanie Smith examines the revolutionary reforms designed to break women’s ties to tradition and religion, as well as the ways in which women shaped these developments.

Smith analyzes the various regulations introduced by Yucatán’s two revolution-era governors, Salvador Alvarado and Felipe Carrillo Puerto. Like many revolutionary leaders throughout Mexico, the Yucatán policy makers professed allegiance to women’s rights and socialist principles. Yet they, too, passed laws and condoned legal practices that excluded women from equal participation and reinforced their inferior status.

Using court cases brought by ordinary women, including those of Mayan descent, Smith demonstrates the importance of women’s agency during the Mexican Revolution. But, she says, despite the intervention of women at many levels of Yucatecan society, the rigid definition of women’s social roles as strictly that of wives and mothers within the Mexican nation guaranteed that long-term, substantial gains remained out of reach for most women for years to come.

Smith analyzes the various regulations introduced by Yucatán’s two revolution-era governors, Salvador Alvarado and Felipe Carrillo Puerto. Like many revolutionary leaders throughout Mexico, the Yucatán policy makers professed allegiance to women’s rights and socialist principles. Yet they, too, passed laws and condoned legal practices that excluded women from equal participation and reinforced their inferior status.

Using court cases brought by ordinary women, including those of Mayan descent, Smith demonstrates the importance of women’s agency during the Mexican Revolution. But, she says, despite the intervention of women at many levels of Yucatecan society, the rigid definition of women’s social roles as strictly that of wives and mothers within the Mexican nation guaranteed that long-term, substantial gains remained out of reach for most women for years to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gender and the Mexican Revolution by Stephanie J. Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Mexican History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Notes

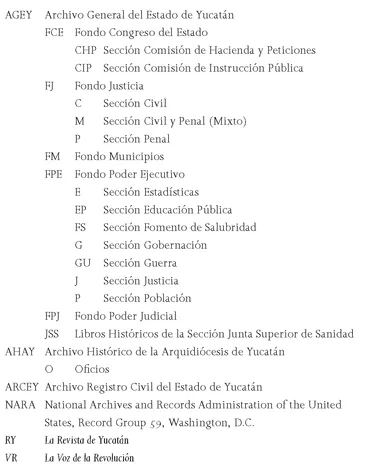

Abbreviations

Introduction

1 AGEY, FM Valladolid, caja 387, vol. 48, exp. 9, 1915; AGEY, FM Ticul, caja 79, vol. 79, 1914-20; AGEY, FM Valladolid, caja 387, vol. 48, exp. 12, 1915; AGEY, FM Valladolid, caja 387, vol. 48, exp. 4, 1915; AGEY, FM Valladolid, caja 387, vol. 48, exp. 3, 1915; AGEY, FJ, C, caja 977, 1915; AGEY, FM Valladolid, caja 387, vol. 48, exp. 18, 1915.

2 I am aware of the difficulty in reading historical texts as well as recent discussions surrounding the topic of the historical archive. See Mallon, “The Promise and Dilemma of Subaltern Studies,” especially 1506-9.

3 Alvarado, Mi actuación revolucionaria en Yucatán, 77. Also see Joseph, Revolution from Without, 108-9.

4 García Peña argues that the Mexican liberal reforms maintained the idea of the natural subordination of women to men in El fracaso del amor, 50. Also see Alvarado, La reconstrucción de México, 2:109-16.

5 Vaughan, “Rural Women’s Literacy and Education during the Mexican Revolution,” 106-7.

6 See Yuval-Davis’s work on women and nation, Gender and Nation.

7 See Kaplan, Crazy for Democracy.

8 Steve J. Stern, “What Comes after Patriarchy?,” 60. Also helpful is Stacey’s discussion of the differences between patriarchy and “post-patriarchy” in “What Comes after Patriarchy?,” and Vaughan, “Modernizing Patriarchy,” 194-202.

9 Besse, Restructuring Patriarchy; Caulfield, In Defense of Honor.

10 This study utilizes Scott’s definition of gender as a “constitutive element of social relationships based on perceived differences between the sexes, and . . . [as] a primary way of signifying relationships of power.” Joan Wallach Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” 42. Also see Weinstein, “Inventing the Mulher Paulista.”

11 Generally, we can define patriarchy as a system of social, cultural, and political control where men exercise power and superior status over women in various aspects of their lives, including their labor and their rights within the family. See Steve J. Stern’s insightful discussion of patriarchy in The Secret History of Gender, 20-21.

12 As Varley notes, women as well as men could reinforce patriarchy within the home, as when mothers-in-law exercised control over their sons’ wives. Varley, “Women and the Home in Mexican Law,” 247.

13 Here I want to thank Florencia Mallon and Barbara Weinstein for their immensely helpful comments on the tensions between patriarchy and gender hierarchy/subordination.

14 Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Patriarchy, 3-11. McNamara also examines the transformation of patriarchy during the Porfirato in Oaxaca in Sons of the Sierra.

15 Stacey, Patriarchy and Socialist Revolution in China, 261.

16 Steve J. Stern, The Secret History of Gender, 21.

17 Similarly, Besse analyzes the modernization of patriarchy under Brazil’s Getúlio Vargas in Restructuring Patriarchy, 202-3.

18 Stacey argues that one of the keys to the success of the communists in China was their ability to harness the patriarchal peasant family to the cause of the socialist revolution, demonstrating that the Chinese communists “saved” the traditional patriarchal peasant family through their land reform and military recruitment policies during the 1920s and 1930s. Stacey, Patriarchy and Socialist Revolution in China, 134-35, 156. Of course, Mexico’s agrarian reform also shored up rural patriarchy.

19 Randall, Gathering Rage; Molyneux, “Mobilization without Emancipation?”

20 For a discussion of liberal theories, see Pateman, The Problem of Political Obligation, 5. Jaggar contends that liberalism cannot provide a philosophical basis for women’s liberation in Feminist Politics and Human Nature. Additionally, MacKinnon argues that the “liberal state coercively and authoritatively constitutes the social order in the interest of men as a gender—through its legitimating norms, forms, relation to society, and substantive polices.” Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, 162.

21 Pateman and other critics of liberalism and the Enlightenment note the ease with which the philosophes and their intellectual descendents reconciled liberal theory and patriarchy. Pateman, The Disorder of Women, 120-21.

22 See Landes, Women and the Public Sphere, 61-65. Also see Joan Wallach Scott, Only Paradoxes to Offer, 63-65; and Hunt, The Family Romance of the French Revolution. While Scott argues that the source of unequal gender relationships lies in liberalism, Hunt instead suggests that patriarchal authority predates the Enlightenment, and its persistence after the French Revolution marks a failure of liberal ideas to completely supplant the culture of the old regime.

23 See Fauré, Democracy without Women, 85-90.

24 Habermas, “The Public Sphere,” 231.

25 Piccato, “Introducción: ¿Modelo para armar?,” 17. For a discussion of Habermas and liberalism in Latin America, see Buffington, “Introduction: Conceptualizing Criminality in Latin America,” in Reconstructing Criminality in Latin America.

26 Revealing the continuity of the ties between liberalism and gender over time, Dore argues that the privatization of land and the legal reform of property rights during the nineteenth century generally “points to a widening of gender inequalities, particularly in Mexico.” Dore, “One Step Forward, Two Steps Back,” 20.

27 For analyses of liberalism’s evolution in Mexico, see Lorenzo Meyer, “Reformas y reformadores”; and Knight, “El liberalismo mexicano desde la Reforma hasta la Revolución,” 59-61. Semo argues that it is difficult to speak only of one strand of liberalism since the political thinking and ideological currents of the time influenced its character. Semo, “Francisco Pimentel, precursor del neoliberalismo,” 475. As an example, see Tutino’s analysis of the links between the development of liberalism and an increase in crime in rural agrarian families during the latter half of the nineteenth century in the state of Mexico in “El desarrollo liberal, el patriarcado y la involución de la violencia social en el México Porfirista.”

28 Hale, The Transformation of Liberalism in Late Nineteenth-Century Mexico; Hale, “Jose Maria Luis Mora and the Structure of Mexican Liberalism.” For the historiography on the pros and cons of liberalism in Mexico, see Hale, Mexican Liberalism ...

Table of contents

- Table of Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- One - Redefining Women

- Two - Broken Promises, Broken Hearts

- Three - Honor and Morality

- Four - If Love Enslaves ...Love Be Damned!

- Five - Women in Public and Public Women

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography