- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

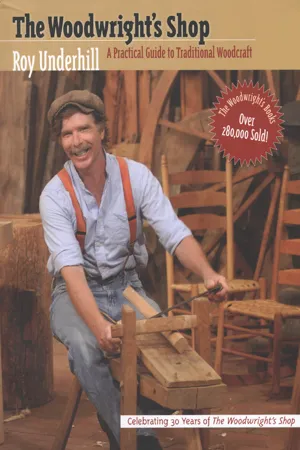

About this book

Roy Underhill brings to woodworking the intimate relationship with wood that craftsmen enjoyed in the days before power tools. Combining historical background, folklore, alternative technololgy, and humor, he provides both a source of general information and a detailed introduction to traditional woodworking. Beginning with a guide to trees and tools, The Woodwright’s Shop includes chapters on gluts and mauls, shaving horses, rakes, chairs, weaving wood, hay forks, dough bowls, lathes, blacksmithing, dovetails, panel-frame construction, log houses, and timber-frame construction. More than 330 photographs illustrate the text.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Woodwright's Shop by Roy Underhill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Technical & Manufacturing Trades. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1. Trees

The best and the poorest grow together, even of the same varieties. . . . It doesn’t seem to be locality so much as it is the individuality of the tree itself. It is something I cannot explain.

—W. G. Shepard in Practical Carriage Building (1892)

Like an old recipe for rabbit stew that begins “first you catch a rabbit,” so in traditional country woodworking you first must find and fell a suitable tree. Even craftsmen who relied on others to fell the timber often bought their wood still in the round log. Before anything else, then, you need to be able to recognize the right tree when you see it, not only by the characteristics common to its particular species, like the toughness of elm, which suits it so well for wheel hubs, but also by the looks of the individual tree.

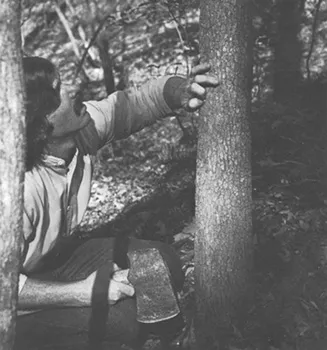

The bark of this white oak spirals up to the right. The wood inside will do the same.

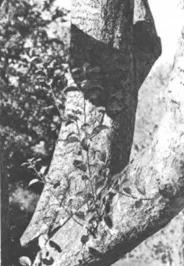

The bark on this old dead red oak showed that it would split straight.

Reading the Bark

Wood forms in a layer of rapidly dividing cells called the cambium, which is located just inside the inner bark. As the tree grows, this layer produces wood to the inside and bark (essentially) to the outside. Since both bark and wood are produced in the same place, some of the characteristics of the wood can be inferred from the appearance of the bark. If the furrows in the bark spiral up the tree, the wood probably does the same. Places where the bark has healed over old branches are easily seen; they, of course, mean knots down in the wood. Soft bark with long flakes is a good indicator of slow growth and tight-grained wood. Daily experience from working with trees from the forests and hedgerows that I see every day has taught me what to look for. This is the only way that you can come to know what to expect from the trees in your particular part of the forest. Look at your trees and see what their outsides tell you about how they have grown. After a while, you’ll be able to look at a tree and tell exactly what sort of chair, basket, or house it has within it.

Sapwood and Heartwood

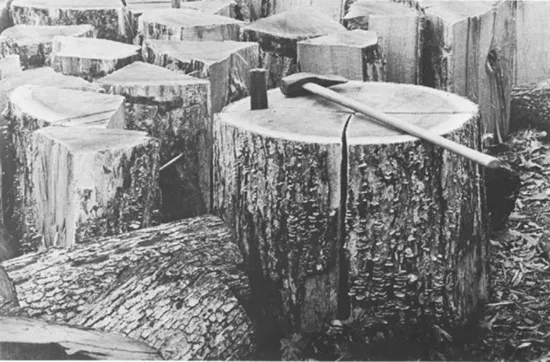

When you chop into a tree as you fell it, notice how the color of the outer few inches of wood is lighter than that further in. In some species the difference may be hard to spot. Only these outer few inches of lighter colored sapwood are alive and functioning; the darker interior wood is essentially dead, but provides the tree with mechanical support. The dividing line between the two is constantly moving outward as the tree grows because the older sapwood to the inside is constantly turning into heartwood.

As the living cells of the sapwood “turn off” and become heartwood, they build up deposits of chemicals called extractives, which are resistant to fungi and insect attack. This passive defense against bugs and rot lasts after the tree is cut. The living sapwood of the tree, however, depends on active, biological resistance, an ability it loses when the tree is cut. This is why any sapwood left on a fence post will rot off long before the heartwood is affected; it can defend itself only when it is alive. This also explains how insects and decay that are able to overcome the passive resistance of the heartwood of a tree but not the active resistance of the living sapwood can completely hollow a tree out without killing it. This last trick is one that we humans have yet to figure out. The properties of heartwood make it very useful to man, and the tree could go on living without it, but we have yet to discover how to get to it without killing the tree.

The heartwood of the maple log on the left was eaten out while the tree was still alive and growing. The sapwood of the red oak on the right decayed when the tree died, but its heartwood is still sound.

Changes

Traditional country woodworking means working with the wood from a living tree. Beyond changing the shape of the wood from the tree, the woodworker also changes its environment. Life inside a tree is very wet; living wood is up to two-thirds water by weight. Once taken down and exposed, however, wood starts drying out and continues drying until it reaches an equilibrium with the relative humidity of its new environment. In wood left outside under cover (air drying), the moisture content drops slowly until it is about one-sixth water by weight. This drying process is known as “seasoning.”

The post-seasoning distortion of wood shaped while green. The red-oak disk has cracked or checked to relieve the stress caused by the shrinkage in circumference being twice as great as the radial shrinkage. The sycamore bowl is now humped on the end-grain sides. The pine board begins to cup slightly near the heart, and the rectangle of the red-oak beam has become lopsided.

But it doesn’t stop there. Fully seasoned wood is at peace with its surroundings only insofar as those surroundings remain constant. If the humidity changes, the wood will absorb or release moisture until it is again in balance. Wood that has been kept in a dry house will take on additional water from the air if it is moved to a damp garage. Firewood from the garage will lose moisture when brought into the house. Water in wood affects its weight, strength, color, dimensions, and a host of other properties. This is what makes wood “alive.” A large part of working with wood is the ability to anticipate and work with these changes.

Strength

A constant source of amazement to the casual observer is the ease and speed with which traditional woodworkers are able to shape their materials. Of course, they know how to use their tools, but more important, they are often working in freshly cut wood. When wood has been freshly cut and is soft and swollen with water, it chops easier, splits easier, bends easier, and saws easier than it does when it dries out.

Green wood does have its drawbacks, however. An article made of wood that is still green is easily broken if it is not allowed to dry before being used. A wooden beam placed in a building before it has had a chance to dry out will often sag under its own weight and dry with the sag in it. The message here is shape the wood while it is green and use it when it has dried. As the wood dries out, its weight decreases and its strength and stiffness increase.

Dimensional Changes

If the strength of wood were all that changed with changes in its moisture content, working with wood would be a lot simpler. But the structure of wood is such that as it dries, it shrinks, and as it takes on water, it swells. Fit a handle of green wood into the head of an axe, and it will come flying off within a week. Drive a peg of dry wood into a hole drilled into rock and pour water on it, and it will split the stone. This swelling and shrinking is why some wooden doors stick in the summer and open up cracks in the winter. The wood is constantly moving in response to changes in the humidity.

But there’s more to this simple swelling and shrinking. Wood also swells and shrinks differently in different directions. Along the length of the grain, change is negligible. A 4-foot length of green firewood will still be 4 feet long when it dries. In the two transverse directions—across the grain—however, the change is quite significant and must be allowed for. In the radial plane (across the growth rings) the shrinkage from green to air dried is about 3 percent. In the tangential plane (parallel to the growth rings) shrinkage is twice what it is radially. This is why a disk sawed off the end of a log will crack open on its radius as it dries. The tangential shrinkage is so much greater than the radial shrinkage that cracking is the only way for the circumference to contract. This uneven shrinkage also causes the distortion of sawn lumber and other articles made from green wood. As long as the weather keeps changing, this motion never stops. You have to learn to anticipate its effects. Design with this potential for change in mind.

Directional Strength

The strength of wood also varies with the direction of the grain. A block of wood stood on end can be split with one blow of the axe. Many strokes would be needed to cut through the same piece of wood laid flat so that the blows cut across the grain. This resistance to splitting (tension failure) is different from what happens when the wood is hit with the flat poll of the axe. In this case the wood is under compression. A blow that leaves the end grain undented will easily smash in the side of the log. This is why the business end of a wooden mallet is end grain.

The shear resistance of wood also varies with the direction of the grain. Imagine clamping a 2-inch cube of wood halfway down in the jaws of a vise and then trying to knock off the top half with a hammer. If you clamp the block so that the failure will be along the grain, this shouldn’t be too difficult. If, however, you try it with the end grain of the block facing upward so that the shear would have to be across the grain, you may knock the vise off the bench.

These general characteristics of the way wood behaves have shaped the world we live in. A great part of the evolution of design has been dictated by the nature of this material. We shape and join our creations with this understanding.

The Trees

There is a right kind of wood for every job. The thousands of different species of woody plants that populate the earth all have their individual characteristics that we have discovered and learned to use to our advantage. We even use this shared knowledge in speaking about one another. Someone called “Old Hickory” is obviously quite a bit different from someone described as “willowy,” but there are places for both—some situations call for toughness and some for grace.

Here are a few of the trees that I work with:

The smooth, platy bark of apple trees is often perforated by yellow-bellied sapsuckers.

APPLE (Malus sp.). This is the tree that taught Sir Isaac Newton about gravity. Apple and pear wood are excellent for making wooden machine parts, especially wooden screws and nuts. The wood takes a deep polish; it is often used in decorative carving and...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Woodwright’s Shop

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Trees

- Chapter 2. Tools

- Chapter 3. Gluts and Mauls

- Chapter 4. Shaving Horses

- Chapter 5. Rakes

- Chapter 6. Chairs

- Chapter 7. Weaving Wood

- Chapter 8. Hay Forks

- Chapter 9. Dough Bowls

- Chapter 10. Three Lathes

- Chapter 11. Blacksmithing

- Chapter 12. Dovetails

- Chapter 13. Panel-Frame Construction

- Chapter 14. Log Houses

- Chapter 15. Timber-Frame Construction

- Sources

- Index