- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In 1950 the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China signed a Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance to foster cultural and technological cooperation between the Soviet bloc and the PRC. While this treaty was intended as a break with the colonial past, Austin Jersild argues that the alliance ultimately failed because the enduring problem of Russian imperialism led to Chinese frustration with the Soviets.

Jersild zeros in on the ground-level experiences of the socialist bloc advisers in China, who were involved in everything from the development of university curricula, the exploration for oil, and railway construction to piano lessons. Their goal was to reproduce a Chinese administrative elite in their own image that could serve as a valuable ally in the Soviet bloc’s struggle against the United States. Interestingly, the USSR’s allies in Central Europe were as frustrated by the “great power chauvinism” of the Soviet Union as was China. By exposing this aspect of the story, Jersild shows how the alliance, and finally the split, had a true international dimension.

Jersild zeros in on the ground-level experiences of the socialist bloc advisers in China, who were involved in everything from the development of university curricula, the exploration for oil, and railway construction to piano lessons. Their goal was to reproduce a Chinese administrative elite in their own image that could serve as a valuable ally in the Soviet bloc’s struggle against the United States. Interestingly, the USSR’s allies in Central Europe were as frustrated by the “great power chauvinism” of the Soviet Union as was China. By exposing this aspect of the story, Jersild shows how the alliance, and finally the split, had a true international dimension.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Sino-Soviet Alliance by Austin Jersild in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Chinese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Mao’s First Visit to Moscow

December 1949–January 1950

Chapter 1

Proletarian Internationalism in Practice

Pay, Misbehavior, and Incentives under Socialism

Unfortunately many Muscovites do not want to understand the simple fact that the PRC is still a young and poor republic, and that their economic regime is not a matter of idle talk; and the voracious eating, sleeping in luxury rooms, and traveling in the international car at the expense of the PRC is not helping things.

—Aleksei Stozhenko to Andrei M. Chekashillo, 1956

—Aleksei Stozhenko to Andrei M. Chekashillo, 1956

The study of the distorted economic incentives of socialism has attracted the attention of scholars of both the Soviet economy and intrabloc exchange.1 The topic is especially interesting for its striking contrast to the many public discussions about the virtues of socialist bloc exchange, which extolled the great accomplishments achieved by bloc “unity” in the struggle against “imperialism,” the rational use of resources and people that served as a contrast to the world of capitalism, and the virtues of new forms of consumption and economic activities. This chapter ignores the grandiose claims about socialism and instead explores the messy and contested business of adviser pay and behavior, Soviet ministerial practices, disputes over contracts, and related matters in China. New archival materials, largely in this case from Moscow, also offer insight into disputes over resources, such as the transfer of blueprints from the bloc to China, that constituted an important part of the advising program.

All of these issues illuminate Chinese frustration with the exchange and the supposedly “selfless” Soviet aid. Colonial inequality and Chinese sensitivity to it again inform the background to the disputes and frustrations described here. The Chinese were far from simply victimized, however. The issue of blueprints, for example, reminds us of Chinese duplicity about their own role in the relationship, and hypocrisy concerning their own frequent rhetoric about “self-reliance.” The straightforward copying of blueprints is tempting for a less developed society struggling to modernize—why not just import the entire industrial product and skip the process of indigenous development? As the discussion of the Changchun Automobile Factory suggests, their claims to “self-reliance” notwithstanding, numerous Chinese industrial officials active in intrabloc exchange expected to use the socialist bloc advising program in this way for their own benefit. The everyday practices and experiences of bloc exchange were far removed from the many sentimental proclamations about the virtues of “proletarian internationalism” and socialist bloc “unity” against “imperialism.”

Komandirovka as a Transnational Institution

The system of komandirovka (work-related travel, or the dispersal of advisers throughout the bloc) was interestingly similar to the administrative practices of the empire of the Russian tsars.2 Imperial Russia also covered the vast multinational territory of Eurasia and devised administrative distinctions and practices that did not conform to national or ethnic borders. Its system of sosloviia (estates) also functioned as a transnational administrative institution, which also clarified the important distinction between those borderland figures loyal to Moscow and those serving a competing power. Imperial officials in the borderlands were eager to cultivate a local elite who would prove worthy of the responsibilities of “subjecthood [poddanstvo]” to the Russian throne, which included forms of privilege and high status that went along with association with the highest soslovie.3 In a time of peasant emancipation and general social reform in the 1860s and 1870s, officials continued to value the estate system and especially the privileged estate as a source of stability and order.4 Reform was for officials an opportunity to incorporate newly educated and capable non-Russians, assuming they were at least from “respectable” families, into the imperial administration. In many cases officials decided to grant high status to those historically not part of the highest soslovie but deserving in their view because of their “service to the State.”5 Officials and commentators thought of the concept in different ways, but in part the notion suggested an occupational category or function, with related expectations about service and responsibility. Importantly, the notion and practice was divorced from national identity. The institution of soslovie was attractive to the state not simply because of the importance attached to privilege in an old regime society but because of its enduring usefulness as a transnational institution of administration, distant from the developing and threatening national question of the imperial era.

The communist party elite of the bloc shared some similarities to the multiethnic service elite that formerly served the tsar in the sprawling and multiethnic empire ruled from St. Petersburg. High-level communist party officials in Eastern and Central Europe now cast their lot with their new rulers from Moscow, “self-Sovietizers” in the formulation of John Connelly, eager to carry out the transformations of their own societies while aligning themselves to the new system of rule from the Kremlin.6 Privilege, opportunity, and security often accompanied the new form of political loyalty.7 There were new bureaucracies, militaries, and national security committee departments to staff and manage. Local communists were eager to benefit from their collaboration with the Soviets, and Soviet officials had a strong hand in the emergence of the new postwar elite and its “psychology,” as a collection of Russian scholars explains.8

The Soviets functioned as administrators of a patron state in its relation to its client parties and administrative elites, inviting them to the Soviet Union for vacations at fancy resorts such as “Sosny” and “Pushkino” on the outskirts of Moscow, to sanatoriums in Gagra and Sochi along the Black Sea, or for special medical treatment at privileged hospitals. There they socialized with party and state officials from other countries in the socialist “camp.” Eastern and Central European communists on holiday enjoyed “delicacies and drinks obtained by phone from Moscow,” as T. V. Volokitina and her colleagues put it.9 The bloc administrative elite frequently experienced these privileged forms of socialization, with Eastern Europeans mixing with Soviet winners of the Stalin prize, members of the Supreme Soviet, engineers, professors, and trade union officials.10 Leftist figures from around the world sometimes visited.11 Maurice Thorez of the French Communist Party flew to Moscow for medical treatment in November 1950.12 Czechoslovak official Karol Tomášek received special ophthalmology treatment in Moscow in 1957.13 Cultural figures were similarly privileged. East German writer Günter Simon enjoyed four weeks with his wife on the beaches of the Black Sea in May 1954 and assured his hosts that the experience had prepared him for future literary work.14 Leading administrative families within the socialist world took these practices for granted. Kim Il Sung of North Korea personally intervened to rearrange study arrangements in the Soviet Union for the son of one of his top officials.15 The wife of the Mongolian minister of internal affairs spent seven months in Soviet sanatoriums and resorts in 1955.16 Relatives of communist party figures from Lebanon, Syria, Iran, Cameroon, and Finland, among others, inhabited this world.17 Sometimes socialist families even intermarried. Stalin’s daughter Svetlana I. Allilueva was married to an Indian communist until his death in 1966.18

The Chinese were now exposed to similar opportunities and privileges. Party cadres, especially those weary from “many years of revolutionary struggle,” enjoyed month-long stays at health resorts and spas in Karlový Vary in western Bohemia (historically “Karlsbad” to the Germans).19 Zhu De’s military delegation spent time in a resort there in January 1956.20 Liu Shaoqi spent a month on the beaches of the Black Sea after attending the 19th Party Congress in October 1952, as did Deng Tuo, the editor-in-chief of Renmin ribao, in the summer of 1955.21 Those who had lived in the Soviet Union sought opportunities there for their children.22 Liu Shaoqi sent his fourteen-year-old son, Liu Yunbin, to the Soviet Union in 1939, where he eventually became a doctoral student in chemistry at Moscow State University, a Soviet citizen, and a party member in 1948. In 1950 he married Margarita S. Fedotova, also a chemist from Moscow State University, and the two of them returned to China to participate in the exchange in 1955. They left behind a three-year-old daughter, Sofia, with Margarita’s parents.23 Before their return to China, they enjoyed an extended stay at an exclusive sanatorium in the Soviet Union, where they were granted all the privileges due “foreign party and social activists.”24 Sophisticated medical treatment for high Chinese officials was also sometimes an option. The future ambassador, Wang Jiaxiang, came to Moscow for this purpose in early 1947, as did the future minister of defense, Lin Biao, in October 1950, also finding time there to address Sino-Soviet planning for the Korean War.25 Yang Shangkun and several other Central Committee secretaries found care in Moscow in the summer of 1952.26 Jiang Qing, the wife of Chairman Mao, almost traveled to Moscow to receive cobalt treatment for skin cancer. Instead, she sent her doctor, Yu Aifun, who returned to Beijing in 1956 with a collection of top doctors, radiologists, and professors.27

The Soviet notion and practice of komandirovka sent advisers, experts, managers, and party officials around the bloc engaged in the collaborative construction of “socialism,” which resulted in the extension of Soviet norms to lands far from Moscow. These figures were not as privileged as the leading cadres of the communist parties, of course, but they too were privileged, politically loyal, and engaged in matters of social and political administration. Most but not all of them were communist party members, especially the most skilled and educated. In China the advisers enjoyed the resorts generally reserved for Chinese cadres in Qingdao and Lüshun, special schools for their children in Beijing, and special shops and forms of transportation. The “Friendship Stores,” today a curious relic long made irrelevant by China’s dynamic economy, were originally created in 1955 to provide special goods for the advisers and bloc visitors.28 The advising communities in Shenyang and Anshan were served by accompanying Soviet physicians.29 In contrast to leading political figures, the advisers at least possessed actual credentials, skills, and educational attainments that they put to use in the far reaches of the bloc. Especially on the China exchanges, many of them possessed a sense of adventure, a desire to travel, and an inclination to share their skills with what they perceived as the needy Chinese. Like “reliable” figures from “respectable” families in the nineteenth century, they were both dependent on the state for their privileges and status and crucial to the state’s administrative goals and projects. Their goal was to facilitate a bloc cohesion and “unity” that transcended traditional national borders, and they functioned with the support of a series of transnational organizations and institutions.

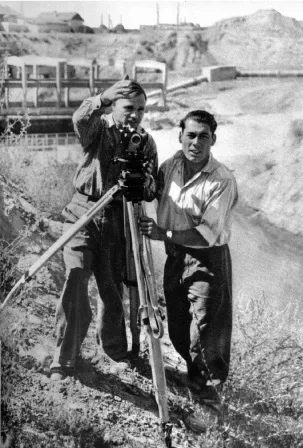

Soviet engineers in China. From S...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Sino-Soviet Alliance

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Mao’s First Visit to Moscow

- Part 2 Mao’s Second Visit to Moscow

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series