- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Folk Medicine in Southern Appalachia

About this book

In the first comprehensive exploration of the history and practice of folk medicine in the Appalachian region, Anthony Cavender melds folklore, medical anthropology, and Appalachian history and draws extensively on oral histories and archival sources from the nineteenth century to the present. He provides a complete tour of ailments and folk treatments organized by body systems, as well as information on medicinal plants, patent medicines, and magico-religious beliefs and practices. He investigates folk healers and their methods, profiling three living practitioners: an herbalist, a faith healer, and a Native American healer. The book also includes an appendix of botanicals and a glossary of folk medical terms.

Demonstrating the ongoing interplay between mainstream scientific medicine and folk medicine, Cavender challenges the conventional view of southern Appalachia as an exceptional region isolated from outside contact. His thorough and accessible study reveals how Appalachian folk medicine encompasses such diverse and important influences as European and Native American culture and America’s changing medical and health-care environment. In doing so, he offers a compelling representation of the cultural history of the region as seen through its health practices.

Demonstrating the ongoing interplay between mainstream scientific medicine and folk medicine, Cavender challenges the conventional view of southern Appalachia as an exceptional region isolated from outside contact. His thorough and accessible study reveals how Appalachian folk medicine encompasses such diverse and important influences as European and Native American culture and America’s changing medical and health-care environment. In doing so, he offers a compelling representation of the cultural history of the region as seen through its health practices.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Folk Medicine in Southern Appalachia by Anthony Cavender in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médecine & Médecine alternative et complémentaire. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Health and Disease in Southern Appalachia

An agrarian existence premised mainly on subsistence agriculture was evident in much of Southern Appalachia well after the onset of industrialization in the 1880s. This chapter examines selected aspects of agrarian life at the turn of the twentieth century relative to the health status of Southern Appalachians and compares the epidemiologic profile of Southern Ap-palachia with rural America and America at large.

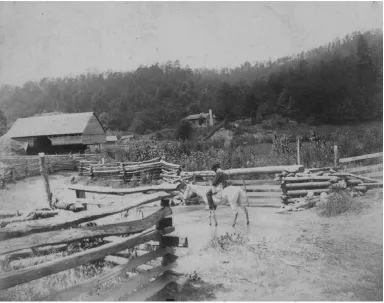

According to a study reported in Ronald Eller’s Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, the average farm in preindustrial Appalachia contained about 187 acres. Roughly 25 percent was in cultivation, 20 percent in pasture, and the rest in forest.1 Corn was the staple crop, but sorghum, potatoes, wheat, and buckwheat were extensively cultivated. Most households maintained a vegetable patch for growing beets, cabbage, turnips, sweet potatoes, potatoes, peppers, onions, beans, and herbs for culinary and medicinal use. Tomatoes were a relatively rare part of the diet prior to the late nineteenth century but gradually became widely cultivated thereafter. Intercropping of squash, melons, and pole beans with corn was common. Many families maintained beehives and orchards of apple and peach trees. Dried fruit was available year around. The diet was supplemented with foods gathered in the wild, including a variety of berries, nuts, and “sal-lets” such as cressy greens, watercress, dandelion, dock, and poke.2 Pinto beans, also known as “brown beans” or “soup beans,” a mainstay of the diet, were not cultivated but purchased at general stores, as was whiteflour, salt, sugar, coffee, canned goods, soda crackers, and exotic fruits like bananas and orang

Most families had one or two milk cows, a horse for transportation, a mule or ox for plowing, a flock of chickens, and hogs, but some kept sheep and goats. Buttermilk was a favorite beverage and much preferred over “sweet milk.” Hog meat, which was smoked or salted for preservation, was a mainstay of the diet throughout the year. Hogs were turned loose in the forest in the fall to forage on the abundant mast.3 Cattle, too, were allowed to forage in forests, which sometimes resulted in, as discussed in Chapter 4, the dreaded milk sickness. Hunting and fishing, both pleasant pastimes for men, provided rabbit, dove, turkey, groundhog, deer, squirrel, opossum, and a variety of fish for the dinner table.

The diet of farming families appears to have been well rounded nutritionally. Unfortunately, however, there were subsistence farming families on tracts of unproductive land in the remote hills and hollows, those known locally as “dirt poor,” whose diet was much like the “three M” diet (pork meat, cornmeal, and molasses) typical of poor sharecroppers in the lowland South.4 One consequence of this diet was pellagra, a disease caused by a deficiency of niacin. Pellagra was reported by missionaries and doctors in the early 1900s as common among poor families in Tennessee, Kentucky, and North Carolina.5 John C. Campbell, a missionary and social scientist, observed that physicians in Southern Appalachia began noticing an increase in the incidence of pellagra in some areas in the early 1900s,6 a period marking the region’s transition into industrialization, which suggests a change in diet coinciding with the shift from farming to employment in low-wage jobs in the mines and mills. Another relatively common disease related to nutrition was goiter, which in most cases was caused by an iodine deficiency. Surveys of selected schools in eastern Kentucky done in the early 1900s indicated a prevalence of goiter ranging from 35 to 75 percent.7

Boiling and frying were the typical methods of food preparation, and both are common in the region today. Pork grease was frequently used for frying meats and vegetables and was poured into cornbread and biscuit batter. Side meat and ham hocks were used to season vegetables. Campbell speculated that the excessive consumption of pork fat was causally related to what he perceived as an unusually high prevalence of “risin’s” (boils) and gastrointestinal disorders.8

Bly family cabin, Mt. Nebo, Blount County, Tennessee, 1886. (Cochran Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee)

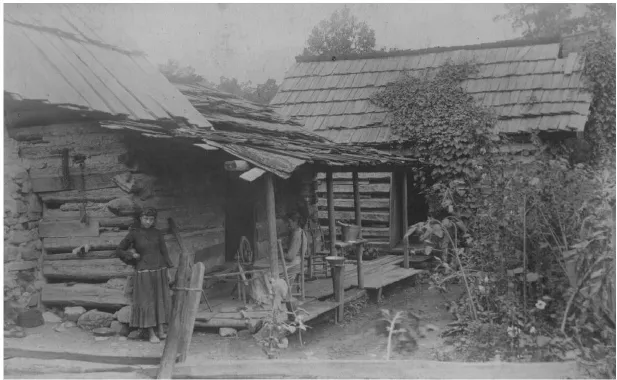

“Auntie Bly” at her spinning wheel, Mt. Nebo, 1886. (Cochran Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee)

Two boys carrying bags of charcoal, Millers Cove, Blount County, 1886. (Coch-ran Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee)

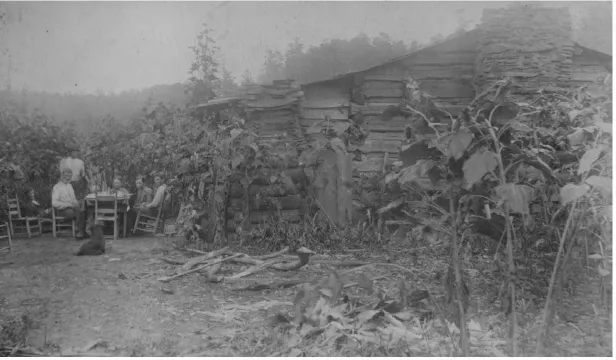

Dorsey family at breakfast, Blount County, 1886. (Cochran Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee)

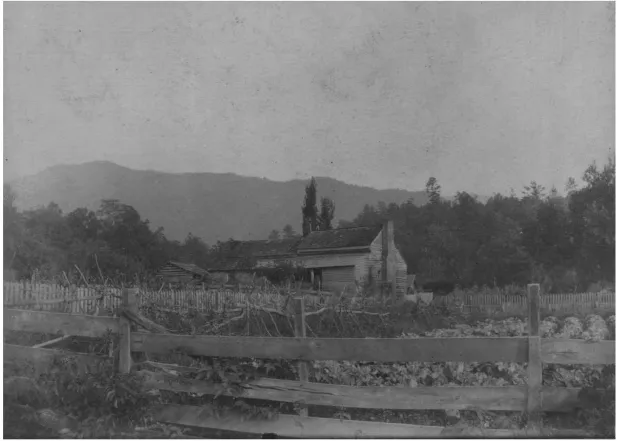

Caughron family farm, Tuckaleechee Cove, Blount County, 1886. (Cochran Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee)

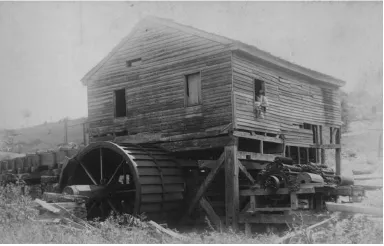

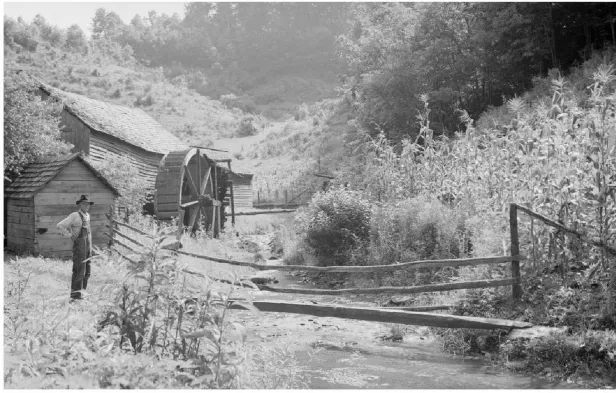

Yearout’s Mill, Tuckalee-chee Cove, 1886. (Cochran Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee)

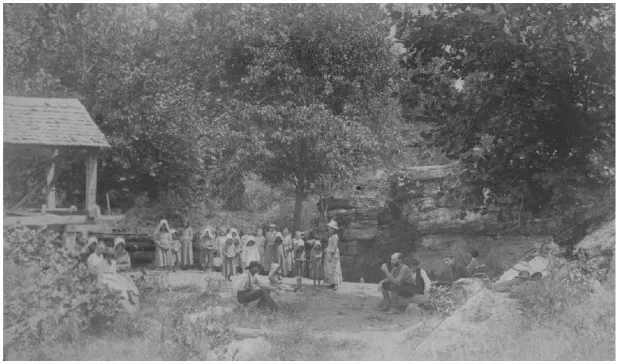

School recess at McCampbell’s Mill, Tuckaleechee Cove, 1886. (Cochran Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee)

D. B. Lawson family home, Cades Cove, Blount County, 1886. (Cochran Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee)

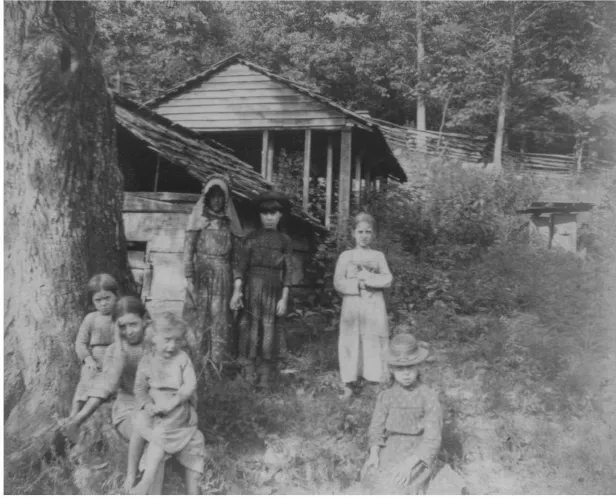

Children gathered at cider mill, Blount County, 1886. (Cochran Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee)

Barn and mill, Pittman Center, Sevier County, Tennessee, 1940. (Albert “Dutch” Roth Digital Photograph Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee; courtesy of Mary Roth)

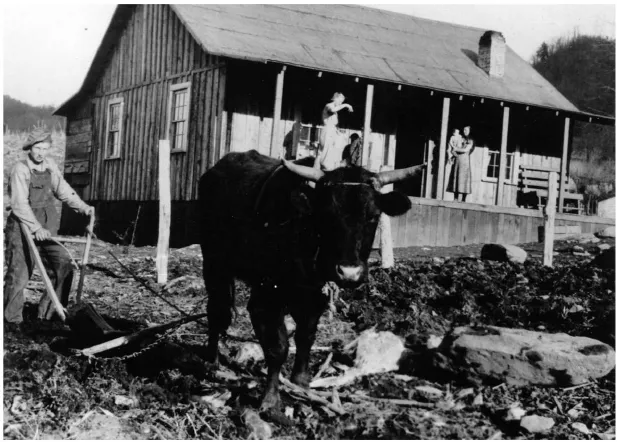

Man plowing with an ox, northeastern Tennessee, ca. 1930s. (Great Smoky Mountains National Park Archives)

Cabin on Roaring Fork, northeastern Tennessee, ca. 1930s. (Photograph by James E. Thompson; courtesy of Thompson Photo Products, Knoxville, Tennessee)

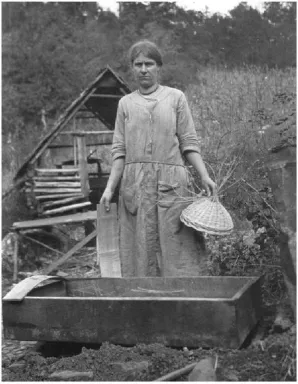

Right: Basket weaver, Roaring Fork, 1926. (Thornburgh Collection, Great Smoky Mountains Regional Collection, University of Tennessee)

Below: Women hoeing, northeastern Tennessee, ca. 1930s. (Great Smoky Mountains National Park Archives)

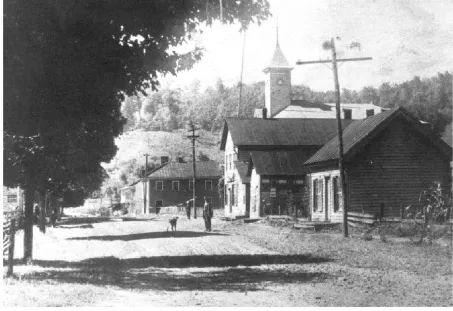

Main Street, Sneedville, Hancock County, Tennessee, 1914. (Courtesy of Charles Turner)

Constructing an epidemiologic history of Southern Appalachia is difficult because birth and death statistics for the region were not included in the U.S. registration area until the early 1900s. Furthermore, statistics subsequently gathered are no doubt flawed by the underreporting of deaths and the lack of accuracy in determining cause of death. The first systematic study of health conditions in Southern Appalachia is John C. Campbell’s analysis of the mortality rates in 1916 for specific diseases in the mountainous areas of Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia as compared to the rural United States and nation at large.9

The mortality rate in Southern Appalachia in 1916 for all causes, 11.2 per 1,000, was lower than that for the rural United States (12.9) and the country at large (14.0). The death rate from tuberculosis in Southern Appalachia was higher (129.5 per 100,000) than that in rural America (124.7) but significantly lower than the national rate (141.6). Campbell notes that the tuberculosis mortality rate in the region was significantly higher in the more densely populated mountain valleys, a pattern that reflects the highly communicable nature of the disease. The death rate for pneumonia was significantly lower in Southern Appalachia (93.8 per 100,000) than in the rural United States (111.3) and the nation (137.3). For measles, the mortality rate in Southern Appalachia of 10.5 per 100,000 was not much different from the rural U.S. and national rates, 10.3 and 11.1, respectively. The typhoid fever mortality rate in Southern Appalachia, however, was significantly higher (28.3 per 100,000) than that of the rural United States (15.6) and the nation (13.3). Other diseases that had a significant impact on the mortality of Southern Appalachians at the time were diphtheria, influenza, cholera, scarlet fever, dysentery, whooping cough, and smallpox. Unfortunately, mortality rates for these and other diseases are not known.

Influenza epidemics appeared time and again in Southern Appalachia, but the worst was the infamous “Spanish flu” in 1918. Estimates vary on the number of people who died worldwide of the Spanish flu, ranging from 20 to 100 million.10 In the United States, the epidemic lasted about a month in the fall of 1918, but during this short span of time it is estimated that a half million people died. In Berkeley County, West Virginia, for example, a local newspaper reported that 350 people died in two weeks and that some 8,000 cases were reported.11 Death was often caused not by the flu per se, but by a lethal pneumonia resulting from it, and men be tween the age of twenty and forty were most vulnerable.12 No area in the region was unaffected, but some fared better than others. The Tri-Cities area of upper east Tennessee mobilized against the flu early and effectively through the implementation of various containment measures. In Bristol, Tennessee, the flu mortality rate of four per day during the peak of the epidemic, for example, was better than Berkeley County’s rate of ten to twelve per day.13

Hookworm was endemic in Southern Appalachia and the South at the turn of the twentieth century. Some observers speculate that over half the children in the South may have suffered hookworm infection.14 Hookworm, malaria, and pellagra came to be known as the “diseases of laziness” because of their severe enervating effect. Progressive reformers in the early 1900s believed that if hookworm were eradicated in Southern Appalachia, the highlander “would have the vigorous, energetic physique naturally expected in one so near to pioneer ancestors, and so would acquire without further assistance all the accompaniments of better living.”15

The living conditions of many families in the region provided an environment conducive to the rapid spread of contagious and infectious diseases. Improper disposal of human waste accounts for the high prevalence of hookworm, typhoid fever, roundworm, cholera, and dysentery. Some families did not use latrines but simply evacuated in a concealed area not far from the house. Those who had outhouses often failed to carefully consider where they should be placed. Thus, waste seepage from latrines, and barns as well, infected wells and streams.16

Large families, in part an adaptation to agrarian labor needs and high infant mortality, were common. Some families lived in small single-room log or clapboard houses with a half-story loft. Most families, however, lived in houses partitioned into two “pens” (rooms). Some of these houses had an exposed hallway, known as a “dogtrot” or “turkey trot,” separating the pens. A chimney was located at the inside center of the house or on one or both gable ends, and many houses had a rear addition that often served as a kitchen. Several children, whether sick or well, slept together in a bed or on a pallet on the floor. Infants often slept in the bed of their parents, even if a parent was sick. All family members used the same dipper for drinking from a water bucket. Close living and sleeping arrangements, which were also evident in families that had more commodious two-story dwellings, promoted the rapid spread of contagious diseases like tuberculosis, influenza, whooping cough, and diphtheria.17

The spread of contagious disease was also enabled by the custom of relatives and neighbors from near and far coming to the aid of families stricken with sickness.18 If it became apparent that someone was going to die, the “death watch” (also called “death vigil,” or “sitting up”) ensued and lasted from a few days to a few weeks. Visitors took responsibility for farm chores, attending children, and taking care of the dying, “even if there was a danger of catching the disease or carrying it to their own family.”19 Following death, visitors assisted with preparing the body for burial with little concern for hygiene. This involved washing the body with soap and water and applying a cloth dipped in soda water, camphor, vinegar, or alcohol to the hands and face to stall discoloration. It is conceivable that disease was transmitted during preparation of the body for burial.

In 1916 the mortality rate for women related to childbirth was lower for Southern Appalachia (12.7 per 100,000) than for the rural United States (15.1) and the nation (16.3), but the infant mortality rate was comparatively high. Infant mortality (death in the first year of life...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Maps & Table

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction. An Overview of Folk Medicine Research in Southern Appalachia

- 1. Health and Disease in Southern Appalachia

- 2. The Folk Medical Belief System

- 3. Folk Materia Medica

- 4. Folk Treatments

- 5. Folk Healers

- 6. Contemporary Perspectives on Folk Medicine in Southern Appalachia

- Appendix A. Archival and Manuscript Sources

- Appendix B. Frequently Mentioned Medicinal Plants in Sources

- Glossary

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index