![]()

Part One

Creating a World for Free Children

Marlo Thomas and children in Central Park during the filming of the Free to Be . . . You and Me television special, 1974.

![]()

The Foundations of Free to Be . . . You and Me

LORI ROTSKOFF

Both before and after Marlo Thomas decided to create a new kind of children’s entertainment, she was involved in the burgeoning women’s movement, fully supportive of the Equal Rights Amendment and other liberal feminist goals. When she began to work on the Free to Be album, she surrounded herself with collaborators whose personal experiences, political inclinations, and intellectual backgrounds shaped their collective commitment to promoting equality and autonomy for girls and boys.

In an interview with a New York Times reporter in 1973, Thomas explained that both sets of her grandparents, who were of Lebanese and Italian descent, were set up in arranged marriages. “My grandfather and his sons would eat in the dining room while my grandmother and her daughter ate by themselves at the kitchen table,” she recalled. And as she has explained more recently in her memoir, Growing Up Laughing, during her youth, within all of the marriages she witnessed among her relatives—including her parents’—“the husband was numero uno. There wasn’t any abuse or that kind of thing. Just the everyday drip, drip of dissolving self-esteem.” At the tender age of ten, Marlo’s budding feminist instincts blossomed into a book she wrote, “Women Are People, Too.” After graduating from high school, she had ambitions to become an actress but instead went to college to study education, as her father had encouraged. Throughout her young adulthood, Thomas remained famously unmarried—and so, too, did the character she played on the hit television show she conceived and produced, That Girl. “I knew I didn’t want to give up my dreams for love and miss them for the rest of my life, like my mother,” she has reflected.1

Thomas’s objection to early marriage was personal, of course, but it also emerged in the context of broader social and demographic changes. Although many of Free to Be’s creators were born before the Baby Boom officially exploded in 1946, they came of age during a time when millions of Americans embraced a mode of privatized, nuclear family life that dovetailed with the construction of new suburbs (such as Levittown on Long Island, New York) enabled by the GI Bill of Rights. When World War II ended in 1945 and veterans returned from overseas, new federal benefits and guaranteed mortgages made homeownership and higher education increasingly affordable, allowing young white men to improve their prospects as breadwinners and embark on marriage and parenthood at an earlier age than any generational cohort before them.2

White women, for their part, were cast in the roles of homemakers, consumers, and family caretakers during the Leave It to Beaver era. Although the majority of women who worked for pay during the war had planned to keep their jobs after the war was over, by the mid-1940s, government policies and employers effectively privileged male workers, pushing millions of female employees out of the workplace and back into the home. These social changes were reinforced in nearly every arena of popular culture, including television shows, advertisements, movies, and magazines, as well in higher education and the mental health professions. From all corners, it seemed, women in postwar America were bombarded with messages exhorting them to marry young, forgo careers, and behave with deference toward men.3

This was the context in which most of Free to Be’s collaborators came of age, but several years before they started the project, they had already begun to chafe against the gender arrangements that prevailed in American society. Battling against barriers they faced in the workplace, they began to carve out lives as independent career women: Marlo Thomas became a prominent actress and producer, Carole Hart began writing acclaimed television shows, Letty Cottin Pogrebin worked as a book publicist, Gloria Steinem launched her career as a journalist, and Mary Rodgers composed songs for successful musicals. These women were pioneers in the public realm well before the women’s movement gathered steam—and, indeed, before some of them emerged as leaders within it.

Another aspect of the postwar domestic consensus against which Free to Be’s creators later reacted lay in the racial and ethnic discrimination that had long defined it. Not only did depictions of the stereotypical Leave It to Beaver family cast American citizenship as a white, middle-class ideal, the financial and federal policies that underwrote the suburbs systematically excluded African Americans and many ethnic minorities from living there. Although white ethnic groups including Jews, Italian Americans, and Irish Americans were frequently able to enter suburban enclaves, government agencies and banks adopted restrictive racial covenants and “redlining” practices to exclude blacks, Hispanics, and other racial minorities.4

Although Free to Be’s principal creators did not personally experience this kind of racism, they objected to racial discrimination and the social injustice that resulted from it. Sympathetic to the civil rights movement and committed to offering an inclusive, multicultural vision, Free to Be’s producers and consultants sought to attract a racially and ethnically mixed audience of listeners. On the one hand, when commissioning writers to draft the stories and lyrics, with one exception they did not hire African American authors or songwriters. (The exception was Lucille Clifton, an acclaimed poet, whose story, “Three Wishes,” was published in the Free to Be book and animated in the television special.) On the other hand, when hiring performers to sing, act, and dance on the album and small-screen segments, they enlisted more than a dozen African American artists and performance groups. In contrast to the white-bread sitcoms that mostly excluded black actors and characters from the prime-time airwaves well into the late 1960s, Free to Be made a concerted effort to depict racial harmony and integration in children’s media and to showcase the talents of popular black performers.5

These social motivations also fueled the Free to Be team when they created the subsequent book. New selections for the printed page explored timely themes, including sibling rivalry in Judy Blume’s “The Pain and the Great One”; war and pacifism in Anne Roiphe’s “The Field”; the intersection of race, class, and friendship in Lucille Clifton’s “Three Wishes”; and the effects of divorce on families in Linda Sitea’s “Zachary’s Divorce.” Artists and photographers contributed colorful illustrations, woodcut prints, and expressive photographs to enhance the book’s message and visual appeal. Reflecting the creators’ desire to incorporate children’s own perspectives, the youngest illustrator, seven-year-old Daniel Pinchbeck, penciled a steam engine and a spaceship to accompany Elaine Laron’s poem “No One Else.” Many pages were devoted to actual sheet music—a direct appeal to music teachers as well as older children or parents who had studied piano.

When the Free to Be team transformed the album into a one-hour ABC television special, they retained eleven of the tracks from the album and added four new pieces. Today DVDs, streaming media, and on-demand cable television allow us to watch programs whenever the mood strikes us. In the early 1970s, though, there were just three major commercial television networks, so a television special aimed at children really was special. Countless children who grew up at this time watched televised holiday specials, such as It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, Frosty the Snowman, and The Grinch Who Stole Christmas, to name a few. ABC began its Afterschool Special series in 1972, preempting regular afternoon programs four or six times a year with made-for-television movies. While Free to Be . . . You and Me was a prime-time special with a variety-show format, it shared the social relevance that many of the Afterschool Specials also conveyed. After the show first aired, McGraw-Hill Films provided schools with copies of the film as well as a “learning module” complete with posters, educational games, craft projects, and teachers’ guides.

In dramatizing children’s literature through music and animation for the small screen, Free to Be shared features with another special that soon followed it. Author Maurice Sendak directed Really Rosie, a half-hour television production based on several of his previous books that aired on CBS in February 1975. The songs in this spirited animated musical featured lyrics by Sendak and music written and performed by singer-songwriter Carole King. (King also sang the vocals for the record album version of Really Rosie released by Ode Records the same year.) Many kids who loved Free to Be also enjoyed Really Rosie, which centered on the antics of an outspoken ten-year-old girl who dreamed of theatrical stardom. Like Free to Be, some of the tunes conveyed lessons on such matters as the value of expressing opinions, showing concern for others, and coping with difficult emotions. Moreover, the fact that the show featured a strong central female character—and one vocalized by a singer and lyricist whose performance style was already enmeshed with the cultural politics of the women’s movement—lent Really Rosie an implicitly feminist air.

Yet among all children’s media productions during the 1970s, Free to Be . . . You and Me was rooted most firmly in the soil of organized feminism. Indeed, the connections between the Free to Be projects, Ms. magazine, and the Ms. Foundation for Women ran deep. Several of the magazine’s founding editors helped facilitate Free to Be’s creation, and when the album was complete, Ms. promoted it to a huge captive audience with frequent ads.6

Even before Marlo Thomas began recording the album, her plan was to channel all the monies raised through the sale of the Free to Be materials into programs that would benefit women and children. When she contacted Gloria Steinem and explained her idea, Steinem responded enthusiastically, telling Thomas that the editors of Ms. were contemplating forming a new foundation for women. It was an ideal partnership, connecting Thomas and the Free to Be project with Steinem, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, and Pat Carbine, who together founded the Ms. Foundation for Women, which grants funds to grassroots organizations and public outreach agencies that serve racially and ethnically diverse populations. As Steinem wrote in her preface to the original Free to Be book, all royalties that would normally have gone to Free to Be’s contributors went instead to support “a variety of educational projects aimed at improving the skills, conditions, and status of women and children.” As Steinem elaborated, this meant “developing new kinds of learning materials, child care centers, health care services, teaching techniques, information and referral centers and much more: all the concrete ways in which this book’s message of freedom can be realized and all the practical changes that are necessary to get rid of old-fashioned systems based on sex and race.”7

While Ms. magazine showed little sign of becoming profitable, the Free to Be project gathered steam, earning enough to support the foundation. By 1975 Free to Be generated sufficient royalties to allow the organization to hire directors and to begin doling out funds. Just a year later, the Ms. Foundation’s grants totaled $87,175, a considerable sum for a budding philanthropic venture at the time.8

At first, the Ms. Foundation planned to focus on funding women in the arts, small businesses, education, and scholarship. But board members soon shifted their emphasis to “survival issues” and “action projects” to empower women across class, race, and age barriers. They began by making small grants, usually up to ten thousand dollars, to grassroots groups focused on issues such as health care, domestic violence, job advancement, migrant workers’ needs, and legal services. Publicity materials explained the foundation’s goal of supporting “changes in women’s lives that are as practical, immediate and inclusive as possible.”9

Free to Be’s creators were also influenced by intellectual currents that flowed strongly during this period, including the field of humanistic psychology. In Free to Be’s conception of a “liberated” childhood, every child is endowed with an internal, true, or “authentic” self: a basic set of personality traits, interests, and inclinations. This notion is best summarized in the final stanza of Dan Greenburg’s poem, “Don’t Dress Your Cat in an Apron”:

Here, the freedom to act on one’s internal motivations is figured as a basic entitlement in a liberal democratic society. This poem and other Free to Be vignettes encapsulated core ideas about human purpose and achievement central to humanistic psychology, a school of thought that developed during the mid–twentieth century as a third alternative to the reigning theories of behaviorism and Freudian psychoanalysis. Emphasizing people’s conscious capacity as self-determining agents, humanistic psychologists focused on how people develop competence, accomplish goals, and engage effectively with others. Abraham Maslow, a major proponent of this theory, popularized the concept of a “hierarchy of human needs.” At the bottom of the pyramid are basic survival needs such as food, clothing, and shelter. Once those needs are met, a person moves up to higher levels, which include social acceptance, love, and self-esteem. Perched at the top of the triangle is “self-actualization,” the optimal expression of one’s unique potential through productive engagement in society at large. Not to be confused with narcissism, those at the peak of human potential work intently to effect positive changes in the world outside the self.10

This last tenet, in fact, made ideas about self-actualization appealing to many activists at the time. Just three years before That Girl premiered on the airwaves, Betty Friedan incorporated humanistic psychology’s dual emphasis on human freedom and human connection into her best-seller, The Feminine Mystique. Friedan, who had studied psychology at Smith College, was disturbed by the fact that relatively few women were able to achieve self-actualization as Maslow had described it. As she argued, the “cultural prescriptions requiring middle-class housewives to devote themselves exclusively to the needs of husbands and children also doomed them to a psychological hell, or at least a decidedly second-class emotional existence.” She continued, “Our culture does not permit women to accept or gratify their basic need to grow and fulfill their potentialities as human beings.” Significantly, Letty Cottin Pogrebin studied personally with Maslow during the late 1950s when she was a student at Brandeis University, and he had a “seismic influence” on her “intellectual and emotional development.”11

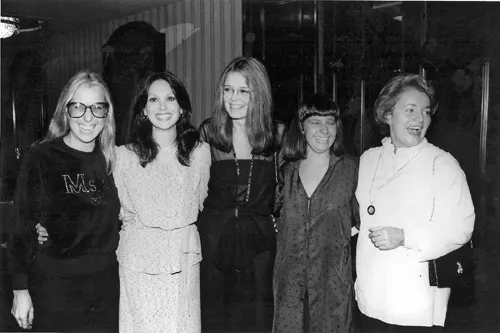

Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Marlo Thomas, Gloria Steinem, Robin Morgan, and Pat Carbine. No date.

Free to Be’s social reach was limited, however, by the fact that these underlying ideas about human potential were forged in a context of relative economic security. Then as now, a person’s ability to “be all he or she can be”—to capitalize creatively and ethically on empowering exhortations to “be free” or “foll...