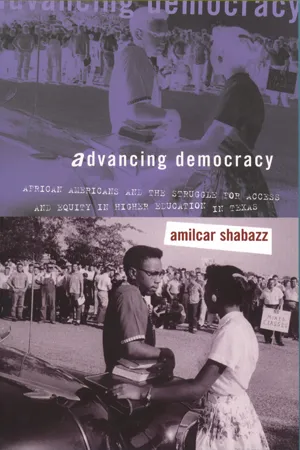

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

As Separate as the Fingers

Higher Education in Texas from Promise to Problem, 1865-1940

Dear readers, come and walk with me on the porch of research for a little investigation. . . . We stand today over 12 million strong. These millions speak, sing and preach in the English language, and beginning sixty years ago our progress has been so marvelous, having now an army of cultured Teachers, Preachers, Lawyers, Doctors, Masters and promoters of business enterprises. Why should we not be inspired to take courage and press forward? . . . [A]ll we ask is an equal chance in the field of endeavor and we will build a monument of honor and love in the hearts of all mankind that shall stand as a sure foundation for us and even unborn generations who will have need to call us blessed.

—Andrew Webster Jackson, A Sure Foundation (1940)

Before black Texans had their own history, schools, churches, warriors, martyrs, and women and men of big affairs, they had Juneteenth. It may not have looked like much in the eyes of an arrogant world, but it was everything black Texans had, and they each loved and cherished that day with all their heart. On the nineteenth of June, they celebrated with their songs of sorrow and joy, they shared the mirth that helped them to survive the long, white-hot day of bondage, their tongues spread the lore that sustained their folk life, and most important of all, they remembered. Facing their past together, the know-it-alls and the know-nothings, the tall and the short, the bright and the blighted, those whose britches seemed to be on fire and those who could go along to get along, they all came together and remembered. Here, from that day forward, they gathered the scattered meanings of their prehistory and put themselves to the task of creating a new collective persona, the freedmen and the freedwomen of the land known as the United States of America. The American soil on which most of them had been born was, however, a land their captors had always claimed as fully theirs and theirs alone. The Euro-Texan claim to ultimate supremacy over the state and its power to control the land is what brought to the Afro-Texans’s Juneteenth an enduring sense of paradox, ambiguity, and irony. Much as they would resist the prerogatives and assumptions of white power, the relative weakness of black power made negotiation a matter of necessity, and negotiate they did. To wrest from white Texans access to the higher educational resources of the state, black Texans had to negotiate a complex system of myths, authority, law, state-craft, prejudice, domination, and psychopathology. The story of how they did this is a significant and fascinating one. Telling no lies and claiming no easy victories, it is clear that the struggle for access and equity in Texas higher education is a vital part of the process of the social construction of black freedom itself.1

From 1866 to 1876, white Texans, against the wishes of the state’s minority black population, created a dual system of public education predicated on the separation of a white race from an African or Negro race. The start of an apartheid system of racial domination in Texas began with the constitution of 1866 with its decree that the “income derived from the Public School Fund be employed exclusively for the education of white scholastic inhabitants” and “that the legislature may provide for the levying of a tax for educational purposes.” The state would direct tax monies raised among people of African descent themselves exclusively toward “the maintenance of a system of public schools for Africans and their children.” Political turmoil and postwar economic conditions, however, prevented the actual development statewide of any public school system.

In 1867, the Reconstruction legislature erased the language of racial segregation. The efforts of ten black representatives at the Constitutional Convention—George T. Ruby, Wiley Johnson, James McWashington, Benjamin O. Watrous, Benjamin F. Williams, Charles W. Bryant, Stephen Curtis, Mitchell Kendall, Ralph Long, and Sheppard Mullins—were a crucial part of the process that helped create public schools and take state government out of the business of maintaining race consciousness. In The Development of Education in Texas, Frederick Eby wrote that despite “the extreme irritation which was felt at the school system imposed by the radical régime, schools were opened; and as attendance was made compulsory many of the colored children attended, this being their first experience of public education.” By 1873, however, the Texas legislature began repealing most of the Reconstruction laws, and the brief and limited episode of nonracial school access became a faint memory.2

In the centennial year of the American War of Independence, a racialistic and inegalitarian spirit seized the hearts of the majority of the legislators in Austin and the white majority of the state’s population at large. Where the constitution of 1869 had been silent on the matter of integrated classrooms, the 1876 constitution was quite definite: “Separate schools shall be provided for the white and colored children, and impartial provision shall be made for both.” State government was again in the role of preserving racial identity, and, more perniciously, it fully intended to deny blacks the “impartial provision” of schools, as well as the “Branch University for the instruction of the colored Youths of the State,” which it had promised them in Article 7 of the constitution ratified on 15 February 1876. Historian Alton Hornsby Jr. speculates that the integration of the University of South Carolina, which resulted from the failure of state officials to establish any institution of higher learning exclusively for blacks, moved Texas legislators to pass a constitutional provision creating a dual system of higher education.3

Six months after Texans ratified their new, more racist state constitution, the state legislature enacted a measure creating a “State Agricultural and Mechanical College for Colored Youths.” The act gave Governor Richard Coke the power to appoint a commission to find a site for the college and supervise the building of its physical plant within a paltry budget of $20,000. The state-supported school that would train the minds of free black men and women, ironically, found a home at Alta Vista, the 1,000-acre slave plantation that became the property of Helen Marr Swearingen Kirby and her husband, Jared, in 1858. In 1867, Helen Kirby, widowed shortly after the Civil War, opened Alta Vista Institute, a boarding school for white girls. She closed the school in 1875 and reopened the institute in Austin. The state of Texas purchased the Alta Vista Plantation from her for $13,000, and because its lands “were exceptionally good for farming and other agricultural purposes,” it became the location for Alta Vista Agricultural College for “colored” people.4

“Alta Vista,” meaning the high view or landscape, did not last long as the school’s name, and the school itself almost died out with it. On 21 January 1878, the state commission concluded its work of preparing the “colored” state college, in compliance with the federal government’s Agricultural Land Grant Act, or Morrill Act, from which Texas had benefited. It formally handed over the stewardship of the new institution to the board of directors of the Texas A&M College, the main branch of which was created in 1871 (but not opened until October of 1876). The A&M directors then named Thomas S. Gathright, the president of the white A&M college, as president of the new black A&M college, requesting that he serve in that capacity without any additional pay. They also hired a black man from Mississippi, Frederich W. Minor, to serve as the institution’s chief operating officer under the baneful title of principal. The title may have caused Minor little distress; he actually constituted Alta Vista’s sole employee: chief administrator, registrar, faculty, janitor—all rolled into one. The white president/black principal dualism, which remained in effect for more than seven decades over the objections of students and supporters of the school, signified the peculiar, subordinate place the school held within a white supremacist society. On its opening day, 11 March, a mere eight students showed up to enroll; but even they quickly fled the plantation school. Like the white A&M branch, Alta Vista only accepted men. The educational function of both the black and white agricultural schools largely involved taking young men fresh off a farm and returning them to the farm as more highly skilled or “scientific” farmers. Alta Vista’s early “black students,” however, as a Texas A&M historian found, “were not interested in college training which would merely return them to the drudgery of farm labor.” Until 1879, the little “colored” school on the high prairie withered on the vine, until Governor Oran Roberts took up the suggestion to convert Alta Vista into a coeducational normal school for the preparation of teachers for “colored” schoolchildren. Under the new name of Prairie View State Normal and Industrial College but continuing under the control of A&M’s board and the white president/black principal arrangement, the multipurpose institution began attracting students. With scholarships from the state treasury and community organizations, as well as the support of popular black political leaders like Norris Wright Cuney of Galveston, Prairie View grew slowly into a major institution of postsecondary education in Texas.5

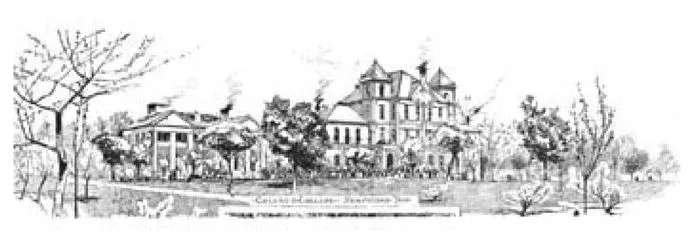

Although the Texas state constitution of 1876 promised to create a branch of the University of Texas “for the instruction of the colored Youths of the State,” legislators established a separate and unequal branch of Texas A&M. Shown in this engraving done in the 1890s is Prairie View’s Kirby Hall, an old plantation house on the left, and Academic Hall on the right (Cushing Library, Texas A&M University).

Cuney, like many blacks of his day, did not rush to endorse the machinations of the white supremacists setting up Prairie View. After Cuney visited Austin in the 1870s, word spread that he had given his support to legislation establishing a state school exclusively for “colored” deaf, dumb, and blind youth. Answering the rumor in his characteristic style of burning forthrightness, Cuney said he opposed segregation in no uncertain terms. Cuney stated that “had the memorial” to establish a special state school for the hearing and visually impaired “been drawn to read that the State should make provision for all her unfortunates, I should certainly have endorsed it, but I do not seek special legislation for the Negro.” He assailed the fact that in Texas only two public institutions showed any eagerness about admitting persons of African descent: the penitentiary and the lunatic asylum. The state-supported institutions of higher learning and the asylum for the hearing and visually impaired were all closed to blacks, he bemoaned. He went on to articulate a clear argument against a dual system of higher education that had to wait over three-quarters of a century before it reappeared before the Supreme Court:

It is a sad travesty upon humanity and justice that the State of Texas accepted gifts of public lands for the endowment of an Agricultural and Mechanical College for the benefit of the whole people, and bars a large proportion of her population because they were born black. . . . No, I do not ask for social equality for my race. That is a matter no law can touch. Men associate with men they find congenial, but in matters of education and State charity there certainly should be no distinction. There is a clause in our State constitution separating the schools. This brands the colored race as an inferior one.6

Ultimately, albeit reluctantly, Cuney became a supporter of the separate-but-unequal Prairie View. He helped many persons to get scholarships to attend the school, and his daughter, Maud, later taught there, as well as headed the music department of the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Institute for Colored Youth in Austin. Both Cuney and his daughter, and black Texans in general, lived in an age of compromises that typically were unfairly cut against black equality. Nonetheless, for every sacrifice of principle, every indignity withstood, they also fought for ground. In 1883, when a Galveston businessman gave the city $200,000 to build a public high school, Cuney, the first African American elected to the city council, demanded that the grant be accepted only if Ball High did not exclude black children. His principled but unsuccessful stand against segregated education and Jim Crow laws faded into the background of Cuney’s pragmatic maneuvering as a politician. Historian Merline Pitre argues that Cuney “was too busy climbing [ladders for political offices] to devote much of his attention to racial matters.” However fair this assessment of Cuney may be, it is clear that accommodation of and rebellion against racial oppression characterized and shaped the lives of black Texans from the most privileged strata to the least.7

In the 1880s, when the state perfected its plans to create the University of Texas at Austin as an institution of the first class for white youths, blacks, including Cuney, protested government officials’ failure to abide by the state constitution and a constitutionally mandated popular vote in 1882 that affirmed that the state would create in Austin a branch of the University of Texas (UT) exclusively for black students. Black educational leaders consistently reproached the legislature’s biased way of administering the state’s dual system of education through the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Despite their protests, the Texas legislature did not deem it “practicable” to establish a “colored branch” of the University of Texas until it faced the possibility of having black students integrate its flagship university in the middle of the twentieth century.8

Texas blacks’ struggle for equal education acquired the reputation of being the most progressive of any state in the postemancipation South. “During the last three decades of the nineteenth century,” one historian has noted, “Texas made greater progress in reducing Negro illiteracy than any other state. . . . Until about 1880 Texas retained her primacy in Negro education, but by 1900 the state had lost this lead” in all areas except the number of black high schools. Moreover, “whites had little sincere interest in furthering the education of the Negroes.”9 Thus, a large measure of the relative advance in black education must be accorded to the actions of blacks themselves.10

A combination of factors enabled black education to get a strong start in Texas. The leadership of public servants like Matthew Gaines and Norris Wright Cuney was a key factor, but the military, through the Freedmen’s Bureau, also played a positive role. Brigadier General Joseph Kiddoo “formalized and expanded the Negroes’ school system” by combining funds from the volunteer groups working to educate blacks with government subsidies. The resulting higher salaries induced many of the northern benevolent agencies’ schools to come under the bureau structure.11

Initially, most white Texans greeted the rise of black education, which to them invalidated the old order, with mistrust and hostility, which soon grew into stern, organized opposition. The evangelical fervor of teachers who came as God’s soldiers of light to “save” a wicked and fallen South enraged the average white Texan. The state newspapers portrayed black freedmen and freedwomen as uneducable subhumans who needed hard work under the scrutiny of whites for their own best interests. A wave of school burnings and physical attacks and threats against teachers and students ensued. One white woman in Houston expressed with pith the mood of the period when she stated that she would sooner “put a bullet in a Negro than see him educated.”12

In spite of Anglo-Texan antipathy, by 1867, the bureau estimated it had taught 10,000 blacks how to read and write. When the bureau withdre...